![]() 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry

1st Battalion 22nd Infantry ![]()

The Syracuse Recruit Camp 1918

Newspaper articles

The influenza epidemic at the

Syracuse Recruit Camp was cause for alarm among the citizens

of the nearby city of Syracuse and the surrounding area. Local

newspapers covered the events

on a daily basis not only concerning the Camp but also the spread

of the disease in the civilian

community as well.

The four articles below are

representative of the press coverage at the time. Mentioned in

the

articles are the two officers of the 22nd Infantry who commanded

the Camp.

|

Officers of the 22nd

Infantry in command Left: Lieutenant Colonel

(Temporary) Right: Captain Sidney F.

Mashbir, who was |

|

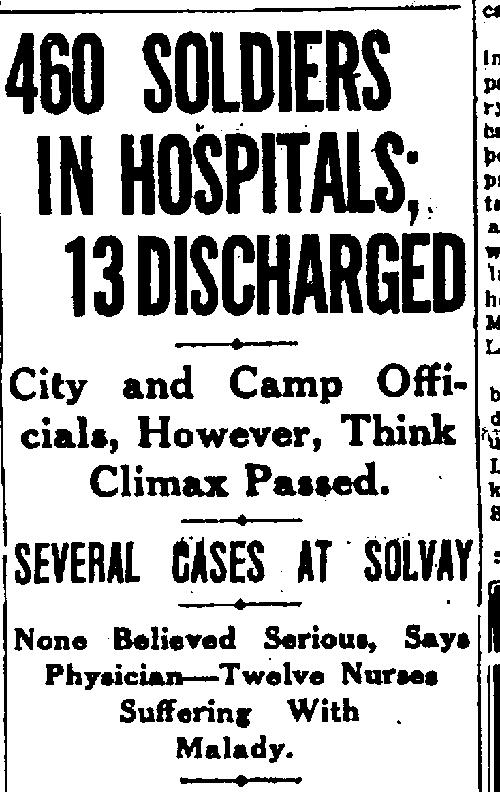

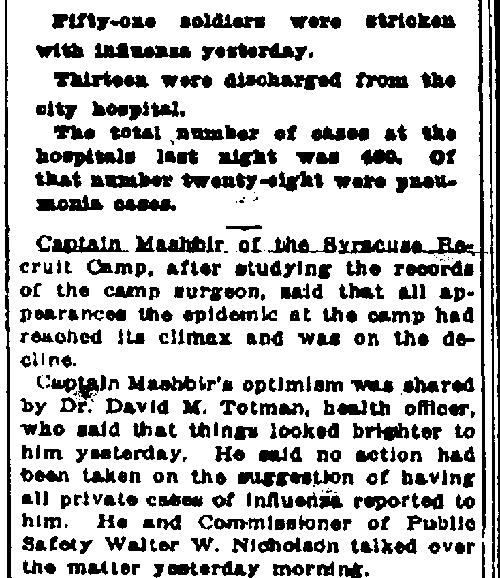

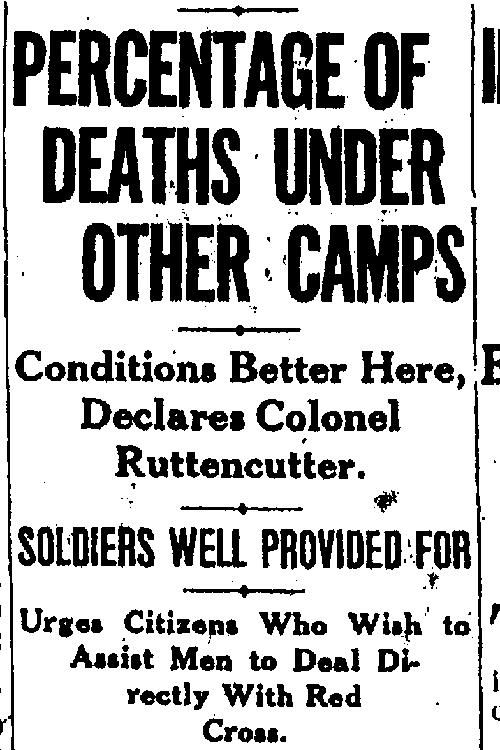

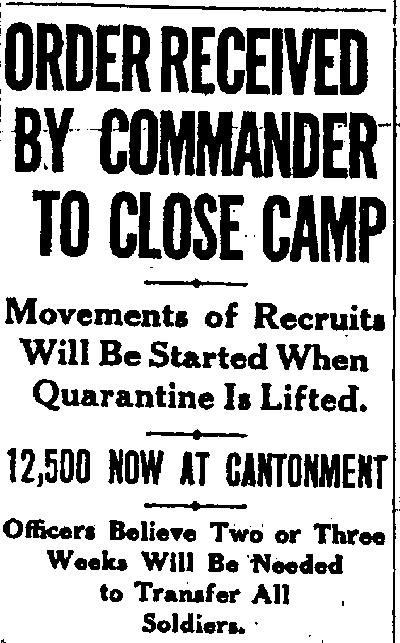

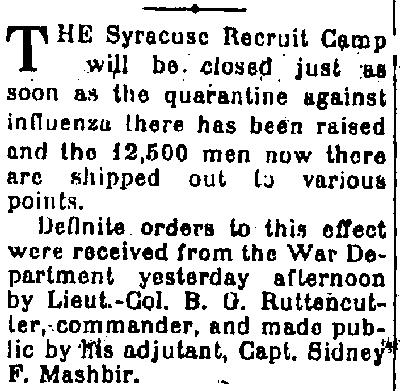

The following article is from The

Post-Standard, Syracuse, New York,

Tuesday Morning, September 24, 1918:

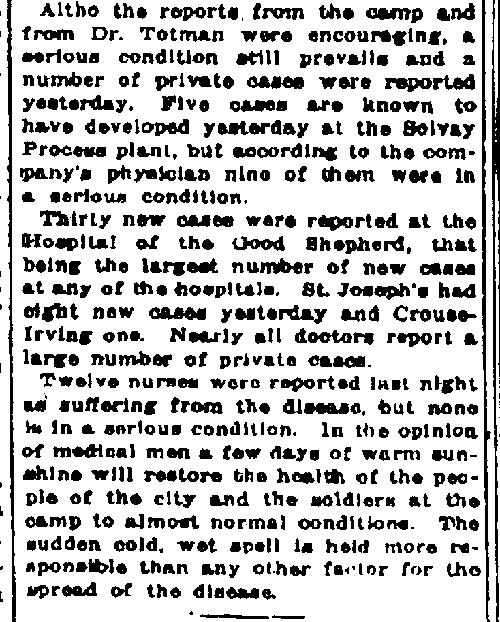

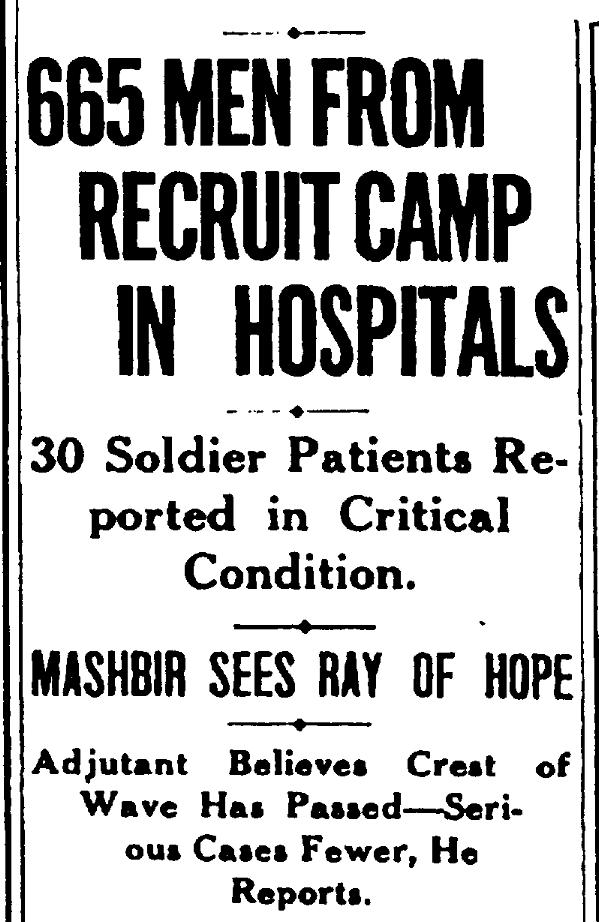

The following article is from The

Post-Standard, Syracuse, New York,

September 26, 1918:

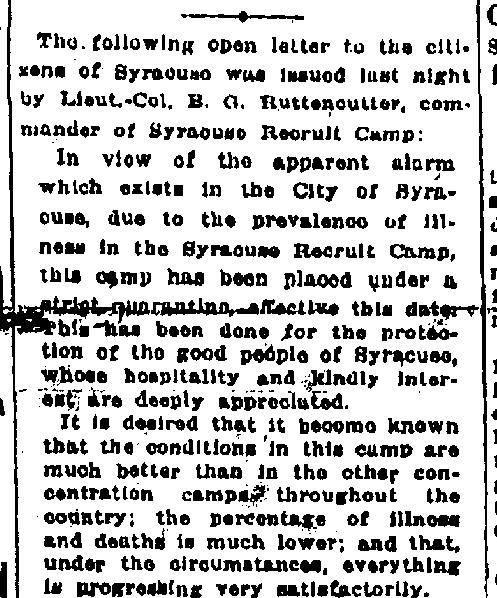

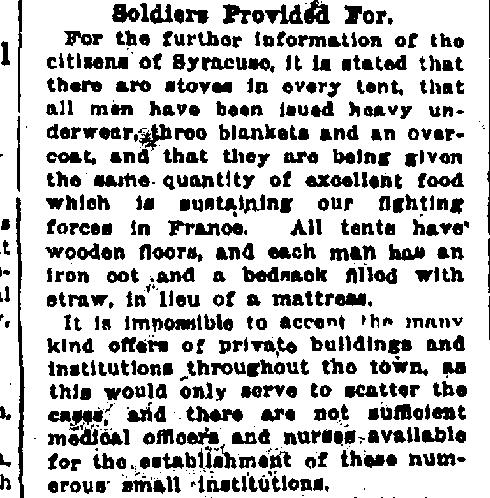

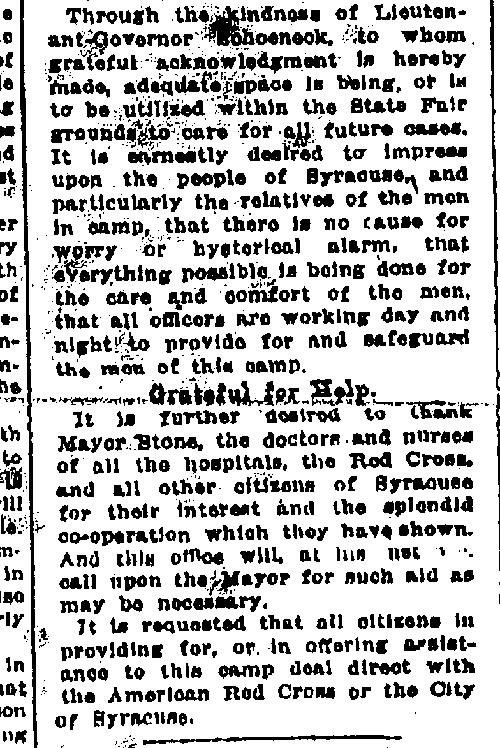

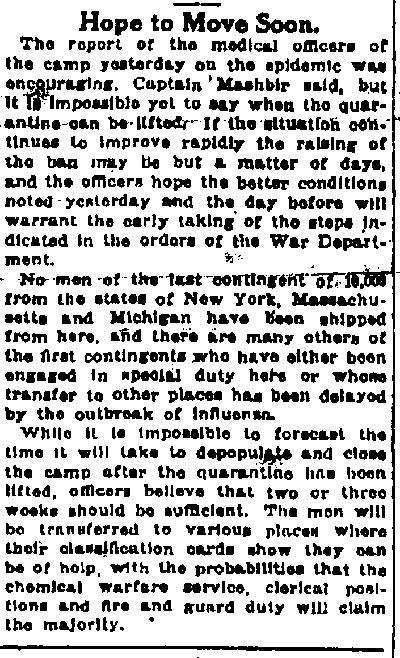

On September 28, 1918 Lt. Col.

Brady G. Ruttencutter, Commander of the Camp, imposed a

quarantine of the Camp

and he wrote a letter addressing the concerns the public had of

the situation. It was published in the following article

in The Post-Standard, Syracuse, New York, September 28,

1918:

Once the epidemic was over and

after a period of quarantine to insure no new cases

of influenza occurred, all personnel were transferred to other

stations and the Syracuse Recruit Camp was closed.

The following article announces the impending closure of the

Camp. It was published in The Post-Standard,

Syracuse, New York, October 4, 1918:

The following essay is from the

Influenza Encyclopedia website and gives a good deal

of historical detail on the 1918 flu epidemic at the Syracuse

Recruit Camp and the resulting

effect it had on the civilians in the surrounding area:

“If we Syracusans are selfish

enough to ask for a year-round camp here, we will have to put up

with this condition all the time during the fall and

winter.” Thus spoke Dr. Dwight H. Murray of the city’s

Crouse-Irving Hospital on September 21, 1918. The condition to

which he referred was influenza, which had recently attacked the

Syracuse Recruit Camp and had put several hundred sick soldiers

into city hospitals. Murray was not the only one exceedingly

unconcerned with the sudden rise of influenza cases. Other

hospital physicians simply chalked it up to “a combination

of germs” resulting from the mixing of soldiers and recruits

from across the country. Even city health officials seemed rather

blasé about it, with one doctor calling it the same

old-fashioned grippe that Syracuse residents had been dealing

with for the past several decades.(1)

Within a few days the number of cases in Syracuse’s

hospitals jumped even higher. Most of the hospitalized were

soldiers, but civilian cases were on the rise as well. Hospital

staff was already working round-the-clock to care for the sick,

and the epidemic had only just begun. Bed space was at a premium;

the Crouse-Irving Hospital crammed 300 influenza cases into a

ward designed to handle only 200 patients. To help alleviate some

of the pressure, hospitals converted specialized wards into

influenza treatment areas. A shortage of nurses led to a call by

the Red Cross for all graduate nurses in the area to assist in

the fight against influenza. The commandant of the Recruit Camp

detailed orderlies to work at the city’s hospitals, where

they were assigned duties in the kitchens, laundry facilities,

and in some cases even the wards. Syracuse threw all the

resources it could muster against the rising tide of the

epidemic, with little apparent effect.(2)

The situation continued to deteriorate rapidly over the next

several days. Finally, on September 28, Lieutenant Colonel B. G.

Ruttencutter, commander of the Syracuse Recruit Camp, ordered the

camp under quarantine.(3) Soldiers were now prohibited from

leaving the camp and mingling with civilians, and civilians were

likewise barred from entering from camp. It is likely that the

quarantine had little if any effect on Syracuse’s epidemic,

however. By this time, hundreds of sick soldiers were being cared

for in civilian hospitals, and countless more soldiers had mixed

with city residents. In fact, civilian cases were now on the rise

as military cases at the recruit camp were declining.(4)

On October 4, after discussing the epidemic situation with

Syracuse Health Officer Dr. David M. Totman and Commissioner of

Public Safety Walter W. Nicholson, Mayor Walter R. Stone

requested that city physicians report all civilian cases of

influenza to the Health Department. It was only a request,

however. As Health Officer Totman stated, “Influenza is not

a reportable disease, and it is too late now to issue a

regulation requiring that it be reported.” Instead,

officials would rely on the cooperation of doctors in order to

obtain accurate case data.(5) The next day, 22 of Syracuse’s

170-odd physicians reported a total of 724 new cases. Totman

estimated that, at that rate, the city had approximately 5,000

total cases of influenza. Mayor Stone took solace in the fact

that this number did not seem proportionately higher than in

other American cities, and he therefore did not see the need to

issue a closure order at this time.(6) For now, Syracuse waited,

hoping the worst had passed.

Only two days later, on October 7, as cases continued to mount,

Mayor Stone ordered all schools, churches, theaters, dance halls,

skating rinks, and other public places closed, and barred all

public meetings, funerals, and other gatherings. The trustees of

the city library system closed all library buildings. Parents

were encouraged to have their children play outside but to

prevent them from congregating in groups. School medical

inspectors were released to work in their private practices, and

school nurses were asked to carry out visitation work for the

health department. No formal isolation or quarantine orders were

issued, but residents were instructed to remain at home without

visitors if they fell ill. Lastly, streetcars were to be

fumigated daily, and restaurant sanitary conditions would be

closely monitored by health inspectors.(7) Mayor Stone asked the

New York State Railways, an affiliation of several urban and

interurban streetcar companies across the upstate region, to

ensure that cars were not overcrowded. The company responded

that, on the contrary, the epidemic had caused a drastic drop-off

in ridership.(8)

To help the anti-influenza effort, Syracuse University suspended

all large classes and requested that faculty and students stay

away from the city’s business district. Cadets in the

Student Army Training Corps were only allowed off campus with a

special pass.(9) Even the Boy Scouts had their activities

curtailed when Safety Commissioner Nicholson ordered them to stop

the door-to-door distribution of Liberty Loan literature and

selling of war savings stamps.(10)

Syracuse’s hospitals struggled to accommodate the increasing

number of patients, prompting officials to announce the opening

of City Hospital to influenza cases provided enough nurses could

be found to staff the facility. Health Officer Totman did not yet

know where additional nurses could be found, as nearly every

community across New York was being hard hit by the epidemic. The

American Red Cross, Visiting Nurses Association, and even the

United States Employment Service were doing their best to put out

the call for trained nurses and volunteers, but demand outpaced

supply.(11)

By mid-October, it appeared that the tide had turned. Physicians

still reported large numbers of cases, but the daily tallies were

declining. The local chapter of the Visiting Nurses Association

reported a similar trend. Mayor Stone and Totman were cautiously

optimistic that the closure order and gathering ban could be

removed within a week’s time, provided the epidemic

situation continued to improve.(12) However, Totman was having

difficulty obtaining accurate case data from physicians, despite

influenza being made a mandatory reportable disease by the New

York Board of Health (effective October 12).(13) Not all

physicians were reporting new cases in a timely manner, and the

state health department pressured Totman to rectify the

situation. Totman responded by reminding Syracuse’s doctors

of their legal obligation to report cases and notified them that

he would report any physician who was remiss. As a result, it was

temporarily unclear whether the epidemic situation was improving,

worsening, or stable.(14) Totman believed that, at the very

least, the existing evidence did not point to a substantial

enough improvement to warrant lifting the closure order and

gathering ban.(15)

Within a few days, however, as reports of lower case numbers

continued to file into the health department, Totman and Mayor

Stone began to believe that indeed the worst had passed. On

Wednesday, October 23, after meeting with Totman and Stone,

Safety Commissioner Nicholson announced the removal of the

gathering ban effective 6:00 am Friday, October 25. Schools would

reopen on Monday, October 28, where each of the city’s

25,000 schoolchildren would be monitored closely for signs and

symptoms of illness.(16) Dance halls, movie theaters, playhouses,

and other gathering places were ordered to fumigate their

premises and to maintain proper ventilation; those that could not

would be forced to make the necessary renovations to allow

adequate fresh air flow. To help avoid a recurrence of the

epidemic, the health department decided to initiate a public

education campaign. The Department printed circulars and posters

warning about influenza and the practices that recently had

helped spread it.(17)

Syracuse’s theaters reopened to capacity crowds as residents

rushed to see plays and movies after several weeks of

entertainment-less evenings. Similarly, church pews were filled

on Sunday. Residents seemed eager to return to their normal

routines of urban life. As the local newspaper put it, “The

red-lettered placards of the Bureau of Health were the only

reminders of the period through which the city has

passed.”(18)

Overall, Syracuse’s excess death rate for the second wave of

the epidemic (September 1918 through March 1919) was 541 deaths

per 100,000 people, a rate comparable to most other Upstate New

York communities as well as cities across the greater

Northeastern region. But, unlike most other area cities (and

indeed communities across the United States)–which continued

to experience cases and deaths through early-spring

1919–Syracuse’s bout with influenza essentially ended

by the last days of November. In January and February 1919, the

city did have a slight increase in influenza cases and deaths,

but the numbers were hardly above the baseline for seasonal

outbreaks of the disease. By far, the worst of Syracuse’s

influenza epidemic had passed by the last days of October.

Footnotes to the above essay:

Notes:

1 “Need Not Fear Epidemic Here of Influenza,” Syracuse

Post Standard, 21 Sept. 1918, 6.

2 “Doctors Work Night and Day Caring for Influenza

Cases,” Syracuse Post Standard, 26 Sept. 1918, 6; “12

More Soldiers Dead in epidemic of Influenza,” Syracuse Post

Standard, 27 Sept. 1918, 6.

3 “Percentage of Deaths under Other Camps,” Syracuse

Post Standard, 28 Sept. 1918, 6.

4 “Camp Officers Gratified by Day’s Report,”

Syracuse Post Standard, 1 Oct. 1918, 6.

5 “Physicians to Report Influenza Cases; 7 Deaths Occur

Among Camp Soldiers,” Syracuse Post Standard, 4 Oct. 1918,

7.

6 “City Takes Steps to Combat Influenza,” Syracuse Post

Standard, 5 Oct. 1918, 6.

7 “Schools, Theaters, Churches and Public Meeting Places

Closed,” Syracuse Post Standard, 7 Oct. 1918, 6;

“Public Library and Branches Ordered Closed by

Trustees,”; “Public Library and Branches Ordered Closed

by Trustees,” Syracuse Post Standard, 10 Oct. 1918, 6.

8 “City Continues Vigorous Efforts to Stamp out Epidemic

Influenza,” Syracuse Post Standard, 10 Oct. 1918, 6.

9 “Large Classes Suspended at University by Dr. Day,”

Syracuse Post Standard, 8 Oct. 1918, 6; “SATC Men Put Under

Quarantine,” Syracuse Post Standard, 9 Oct. 1918, 6.

10 “Activities of Boy Scouts Curtailed by the

Epidemic,” Syracuse Post Standard, 9 Oct. 1918, 6.

11 “City Continues Vigorous Efforts to Stamp out Epidemic

Influenza,” Syracuse Post Standard, 10 Oct. 1918, 6;

“Appeals for Aid,” Syracuse Post Standard, 10 Oct.

1918, 6.

12 “Drop in New Cases of Influenza Indicated in

Physicians’ Cards,” Syracuse Post Standard, 15 Oct.

1918, 6.

13 State of New York, Thirty-ninth Annual Report of the

Department of Health, for the Year Ending December 31, 1918, Vol.

1 (Albany: J. R. Lyon Company, 1920), 86.

14 “Health Officer Orders Doctors to Report Cases of

Influenza,” Syracuse Post Standard, 17 Oct. 1918, 7.

15 “New Cases of Influenza Slowly Decreasing Here,”

Syracuse Post Standard, 19 Oct. 1918, 7.

16 “Ban on Public Meetings Will End on Friday,”

Syracuse Post Standard, 23 Oct. 1918, 7; “Schools Again Take

up Work Following Ban,” Syracuse Post Standard, 28 Oct.

1918, 6.

17 “Teach Public How to Avert Second Plague,” Syracuse

Post Standard, 24 Oct. 1918, 7.

18 “Theaters and Churches Filled to Capacity Show Fear of

Epidemic is Over,” “Theaters and Churches Filled to

Capacity Show Fear of Epidemic is Over,” Syracuse Post

Standard, 28 Oct. 1918, 6.

The above articles and the essay

at the bottom are from the Influenza Encyclopedia website,

produced by the University

of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan

Publishing, University of Michigan Library.

To read many more articles

concerning the influenza epidemic at Syracuse in 1918

go to the following link:

Articles on the Syracuse influenza epidemic of 1918

Home | Photos | Battles & History | Current |

Rosters & Reports | Medal of Honor | Killed

in Action |

Personnel Locator | Commanders | Station

List | Campaigns |

Honors | Insignia & Memorabilia | 4-42

Artillery | Taps |

What's New | Editorial | Links |