![]() 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry

1st Battalion 22nd Infantry ![]()

The Jungle

Firebase LZ Regular

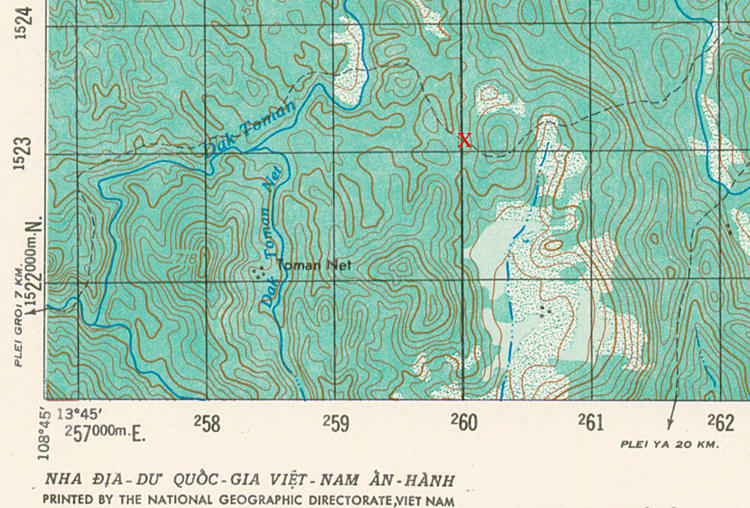

Our weapons platoon was 4th Platoon, known as “Popeye”. In September 1970 its mortars were left at the Base Camp and its personnel were assigned to the rifle platoons and humped the boonies with us as riflemen. Sometime late in September or early October the guys from weapons platoon were picked up out of the jungle by Huey helicopters and airlifted to grid reference BR 600233 to build a small firebase. Along with some Engineers they built a base on a hilltop that jutted out into an area where several other hilltops and valleys met together. It was called LZ Regular. (Not to be confused with an earlier firebase for 1/22 Infantry, which was called LZ Regulars and which had been built further west near the Cambodian border at grid reference YA 614600.)

A portion of grid map

sheet 6736-I showing LZ Regular marked with a red X at grid

reference BR 600233.

This map is a 1965 version, and by September 1970 the village of

Toman Net in the lower left center had long been abandoned.

LZ Regular consisted of a battery of two or three 105mm howitzers, the 81mm mortars of Company C’s weapons platoon and a small ground radar outfit. At some time after its construction, 3rd platoon (my platoon) was airlifted out of the jungle and brought to the firebase to act as security. To the best of my memory our platoon guarded one half of the firebase and the personnel for weapons platoon guarded the other half. There may have been another platoon there as well but I can’t confirm it. It seems likely there should have been more than two platoons at that base, but it was pretty small as I remember, was not the Battalion Headquarters firebase, and there may well have been only our two platoons at it.

The little firebase was devoid of trees or bushes, and on three sides the surrounding jungle was lower than the firebase. The firebase was on a "finger" which jutted out into the valley. The north end of that "finger" was a little higher than the firebase, and was to the right of my assigned position. One day an element of four or five guys from Battalion Recon was airlifted to the firebase, and began their mission by walking up that finger and disappearing into the jungle. They stayed in our platoon area for a while before starting their patrol, and I had a chance to talk with one of them. He had 30 round magazines for his M-16 rifle. He told me his outfit had them made in country by a Vietnamese craftsman, and that they worked quite well.

Almost every day close to sundown we were encouraged to fire our weapons for a while into the surrounding jungle. During that time I was able to practice a “point and shoot” technique of firing my rifle without actually aiming through its sights. I would point at a target, usually a tree on the edge of the jungle and fire into it. I used magazines into which I had loaded tracer rounds staggered every few shots or so. By watching the red tracers I was able to learn to correct my point of fire, until it became second nature to me as to where to point the rifle, to hit a man sized target at a little bit of distance, without aiming. After our daily shooting exercise was done the f**k you lizards would start their chorus of chants. It was crazy to hear dozens of them all shouting their famous call for several minutes while the sun went down.

Once, on a cloudy day we heard a jet flying above us reasonably low. We couldn’t see him because he was in the clouds, but we could hear him. Suddenly, in the valley on our right over beyond a ridgeline two huge explosions erupted, with dark blossoming clouds of smoke billowing up from them. The sound was loud and the ground beneath us shook. The jet had dropped two bombs very near to the firebase. A bunch of guys headed for the bunkers or foxholes. We were mystified. No one had called for an airstrike. We never learned why the guy dropped those bombs. The bombs hit very close to us and scared a few guys.

One side of the firebase sloped down to a valley covered in brush and jungle. That slope was covered with razor grass of about four feet high. One day I was detailed to lead a patrol of about seven guys down off the firebase. We were instructed to go down into the valley and move through the jungle and brush about 500 meters, then to turn to the right, move about 200 meters or so and come back to the LZ along the base of another ridgeline that paralleled our firebase.

As we entered the jungle at the bottom of the hill we encountered hundreds of leeches. They were everywhere, and stood on end as if they could smell our blood and were trying to latch onto us. We moved through that area as quickly as we could, and then came into an area of bamboo. This bamboo was thin, maybe an inch or so thick, and instead of growing straight up to its full length, it grew vertical for about three feet, and then bent over and laid down horizontally, and wove together to form a shelf amid small trees under the jungle canopy. That shelf of bamboo was strong enough to support a rifle laid upon it or something a bit heavier. We could actually sit on it in most places. I tried climbing on top of it and walking on it but my leg punched right through it and I was left sitting on top of the bamboo shelf with my leg dangling into empty air underneath it. So we had to chop our way through it with a machete. That was tiring work and the guy doing the chopping had to be rotated until we finally got through that area.

After we made it out of the bamboo we moved through jungle a ways, and then it was time to turn to the right and make our way to the base of the ridgeline along which we would return to the firebase. The jungle thinned out into brush and open areas along the base of that ridgeline. Since we all had taken turns chopping through the bamboo, once we got to the bottom of the ridgeline, we stopped and took a rest in the shade of some fruit trees. Those trees had a yellow/orange fruit that some of the guys ate and thought tasted pretty good. I tried one but didn’t like it much. Years later I would find out it was a variety of wild mango.

We moved along the bottom of the ridgeline for a few hundred meters and then began the climb uphill back to the firebase. I took the point and led the patrol up the slope. The trek up the hill was through the four feet tall razor grass. I wore my shirt sleeves rolled down and fastened at the cuff while out in the boonies, but the bare skin of my hands were exposed. The razor grass sliced up my hands with the severity of paper cuts so I held my arms above the grass as I made my way through it. That grass snagged my fatigues and gear, and it was as if I were struggling against someone who was trying to hold me back as I trudged up that hill. By the time we got to the top and entered the firebase most of the guys were pretty well spent. I was so worn out I wasn’t sure I could make it across the base to my bunker.

At that moment the enemy opened up on us from somewhere on the ridgeline, the bottom of which our patrol had walked along only minutes earlier. Small arms fire cracked overhead and sent guys hustling for cover. I was so tired I could barely put one foot in front of the other, so I leisurely walked over to the nearest bunker to get behind, and plopped down next to Dotson, our platoon Sergeant, who was crouched behind the bunker with his rifle at the ready. He fussed at me for sauntering over so slowly, and asked if I was too stupid to know I was being shot at. Using some vivid four letter words I spit back at him that I didn’t care if they shot me. He looked at me as if I were truly insane and had just said the craziest thing he ever heard.

I explained to him that I and my patrol had walked several hundred meters along the bottom of that ridgeline, mostly out in the open and even though we didn’t know they were there, those bad guys on that ridgeline obviously watched us the whole way. They could have shot us up at any time they wanted to, but didn’t. What I didn’t explain to him, was that at that moment I was too tired and aggravated to be scared. It wasn’t bravado, I was just plain worn out and exhausted.

The artillery on our firebase fired some high explosive rounds into that ridgeline and the enemy stopped shooting. After a while our Lieutenant led a patrol up that ridgeline looking for those bad guys. They went up a trail to the top and found no one. Wayne “Andy” Anderson was walking last in line in that patrol. Andy noticed something on the side of the trail and when he investigated it, found it was an enemy booby trap. The enemy had wired a c-ration or other tin can to a sapling and stuck a hand grenade inside the can with its pin pulled and the handle squeezed. A trip wire had been tied to the grenade and then strung across the trail and tied to a sapling on the other side of the trail. The idea was that a G.I. would walk into the trip wire, which would pull the grenade from the can, thereby releasing its handle, which ignited its fuse, and the grenade would explode. Whatever wire the enemy had used as a trip wire had rusted and deteriorated, and remnants of it could be seen laying on the ground coming from the can. So even if the wire had still been strung across the trail when the point man walked into it, instead of pulling the grenade from the can the wire just broke. Good thing because the entire patrol had walked right by it without seeing the booby trap. The only one who noticed it was Andy, who was the last guy in line.

Life on the firebase was a welcome relief from bashing through the jungle. When the firebase was dismantled my platoon pulled security while all the equipment at the base was airlifted out by large Chinook helicopters. Those Chinooks had a set of big rotor blades at the front and a second set of big rotor blades at the back. The rotor wash made from those two big sets of blades, as they hovered above the base to pick up their loads, was similar to being under gale force winds. After they hauled off their final loads, it was a long while before Huey helicopters came to pick up our platoon. Long enough for us to worry they had forgotten us. When they finally came, the Huey’s brought us back out into the jungle where we again resumed humping the boonies for another week or so, until our part in Operation Wayne Forge was over. By the time we were finally pulled out of the jungle and flown back to our Base Camp (Camp Radcliff) at An Khe for a rest and stand down, it felt to me like we had been in the boonies for years.

The Vietnamese rat

The Vietnamese rat was a mighty creature. It lived everywhere the US infantryman went in Vietnam. Firebases, base camps, mountains or coastal plains, no place was safe from its onslaught. It was ugly, big, fearless and hungry. An Eleven-Bravo (infantryman) in Vietnam either killed rats or learned to live with them. Their presence was a fact of life.

Sergeant Huey Livingston was Squad Leader for 1st Squad, 3rd Platoon of Charlie Company, 1/22 Infantry, 4th Infantry Division in the fall of 1970. He had guts and experience, two qualities that were very important for a Squad Leader in the jungle. He came from the Deep South, a hard drinking dusty-haired good old boy in every sense of the word and he was an excellent man to follow up and down those triple-canopied jungle covered mountains of Binh Dinh Province.

Livingston appeared to be afraid of nothing, most certainly neither man nor beast, with one exception. He really didn’t like rats. The presence of one of the hairy animals could move him into furious spasms of action. His initial reaction was always the same. A slow and orderly withdrawal was unthinkable. His plan of action called for immediate removal of himself from the area, bulldozing anyone or anything in his way. Upon reaching safety he would then counterattack with ferocity unmatched in human history. The rat that surprised Livingston sealed its own fate and found itself with only minutes, even seconds left to live.

Huey Livingston at the

Base Camp at An Khê with his ever present can of

Pabst Blue Ribbon beer August 1970

Photo by Randy Cox

Sometime in October 1970 our Platoon was rotated to a firebase to get a breather from humping the jungle. The firebase was small. It was on a hilltop that jutted out into a valley surrounded by three higher hilltops. There were two or possibly three M102 105mm howitzers there, I don’t remember for sure but they were probably from 4/42 Artillery. There was also a ground surveillance radar unit. As I recall that unit was some kind of people detecting wizardry and at one time one of our guys came back from visiting the radar and its operators, impressed that the radar had spotted several enemy soldiers walking in the jungle passing by us carrying what might have been B-40 rockets.

Our Weapons Platoon had been reassembled from the various Rifle Platoons its personnel had been assigned to and had their 81mm mortars set up at the firebase. We had moved deep into the mountains beyond the range of any artillery on any existing firebase. Engineers had been flown out and together with Weapons Platoon they built this firebase so a couple of artillery pieces could cover our movements. The hilltop this firebase had been built on was selected because it was devoid of trees, being covered instead with razor grass which grew about four feet tall and was so named because the minutely serrated edges of each blade of grass could scratch and cut exposed skin when rubbed against it.

I remember the firebase being called LZ Regular but Gary Rabideau from Weapons Platoon, who was one of the guys who actually built the firebase remembers it being called LZ Popeye. Popeye was the nickname of Weapons Platoon for our Company. Weapons Platoon guarded one half of the firebase and our Rifle Platoon (nicknamed Sidewinder) guarded the other half.

Our outer perimeter consisted of sandbag-ringed foxholes with no overhead cover. The inner perimeter was made of covered bunkers used as sleeping quarters. Gary and the guys from Weapons Platoon had large 4 foot wide semi-circle culvert sections on their side of the firebase covered with sandbags as sleeping quarters. On our Rifle platoon side we had a square bunker used as sleeping quarters for the position I was assigned to. This bunker was dug into the ground and had thick timbers for the roof which had been air lifted out to the firebase by large Chinook helicopters. The timbers were covered by sheet plastic with a layer or two of sandbags on top of that. The bunker had a single entrance and inside there was room for either 3 or 4 men to sleep side by side on their air mattresses.

The bunker was deep enough so you could sit upright in it or crawl on your hands and knees but not deep enough to stand up in. The dirt just below the roof had been scraped out, making a recessed shelf that ran all the way around the inside. The shelf was perfect for small items including a jungle candle (made from the wax and paper insulation wrappings of mortar shells) or the more customary, a c-ration candle, made of a tin of peanut butter to which we would add liquid insect repellent. The oil from the peanut butter mixed with the chemicals in the insect repellent burned like lamp oil in the small short tin the peanut butter came in and gave off light like a small hurricane lamp.

The rats of course got in our bunker as well and you could count on seeing one of them in the bunker just about every day. An entrenching tool or a well-placed foot would usually dispatch them quickly enough. One day I went into our un-occupied bunker to get something and was carrying my loaded rifle. As I came through the entrance, thanks to the light from a burning candle inside the bunker I saw a rat on the shelf opposite me a few feet away. I flipped off the safety on my rifle and blasted the rat.

Blast is the right word. In the confined and enclosed space of the bunker the single shot of the high velocity M16 rifle erupted like an atom bomb. Since there were no windows or slits in the bunker and my body was blocking the only opening, the sound and concussion had nowhere to go but right in my face. The sound was deafening and the pain from the sudden and violent displacement of air molecules against my head, nose and ears was intense. I felt as if two giant hands had clapped together hard, with my head in between them. I never again made that foolish mistake of firing a weapon inside an enclosed bunker.

Livingston had decided he wasn’t going to sleep inside the bunker with the rats anymore. He placed his air mattress on the sandbagged roof of the bunker. One evening as three of us stood next to the bunker having a conversation Livingston settled onto his mattress and lay on his back in the dimming light of dusk. Very soon after he fell asleep a rat appeared out of nowhere and sat next to his feet. We watched with amusement as the rat climbed onto Livingston’s boot and slowly made its way up his body. It would move a few inches, stop and rub its nose or wiggle its whiskers or just sit there looking so comical that we all started to snicker and laugh. It would move a little farther and stop again and look at us and then look at Livingston before continuing its trek up his leg, over his knee, up his thigh, carrying on its journey across Livingston’s body.

By the time it got to his waist we were doubled over with laughter, holding our hands over our mouths to stifle our sounds. The rat continued and then stopped on his chest and at that moment Livingston awoke and found himself eyeball to eyeball with the rat. We exploded with shrieks of laughter so deep it brought tears to our eyes. Shillings was laughing so hard he was rolling on the ground.

Livingston jumped up and flew off that bunker ending up several yards down the hill. We all scrambled for cover as he found his rifle and assaulted the rat. The rat however, had already sought refuge and was nowhere to be found. Livingston’s curses could probably be heard throughout the whole valley. We enjoyed telling that story for weeks, each time ending it with Livingston’s declaration “god-damn rats!”

Henry Shillings – a

seasoned veteran who teased me unmercifully about being a new guy

(FNG) when I was first assigned

to 1/22 Infantry. He and other experienced soldiers like Huey

Livingston, Ron Sorrento and David Hester taught me a lot about

how to survive in the jungle. I took this photo at the Base Camp

at Camp Radcliff, An Khê in late 1970 as we were posing for

photos

with captured enemy weapons.

Back to Base Camp

Once we got to the Base Camp and got a good night’s sleep most of us enjoyed the luxury of taking a shower the next day. Our shower was a wooden structure, on top of which sat a couple of large metal tanks of water. During the day the sun and heat warmed the water in those tanks, so we stood under pipes coming from them and washed, pulling a chain hanging down to open the valve and let the warm water from the tanks come down those pipes, and on to us to rinse us off. After not bathing or showering for a month and a half it sure felt good and made us feel almost human again. When someone who had not yet showered came near one of us who had, his smell was foul and overpowering. We didn’t smell ourselves or others while we were out in the jungle. Out there we had literally become one with the jungle. We looked like it and smelled like it until we were able to wash it off of us. Within a few days we were all made to get haircuts.

Back at the Base Camp we were detailed to guard duty in the bunkers and towers on the perimeter line of the base. Less than a week after returning to the Base Camp, one morning at about 7:00 am as we returned to the Company area after being relieved from guard duty, the enemy fired about a dozen 122mm rockets into our Battalion area, several of which landed in my Company’s area. I was walking toward the open door to my Platoon barracks and was a few feet away from it when the first rocket hit. The explosion sounded really close and I flung myself through the doorway onto the floor of the barracks. Moments later, when the second rocket landed, I got up and ran to the nearest protective bunker, which consisted of half a big metal culvert covered by sandbags. I could hear the rockets “hiss” as they came in. I was the first one in the bunker but in less than a minute I was joined in it by enough of my buddies to fill the bunker. We stayed there until the “all clear” was given.

Not long after we were back, we held a Battalion formation at some open area of the Base Camp. Some guys were awarded medals. In front of our formation there were three sets of jungle boots, with an inverted rifle stuck in the ground on its bayonet behind each set of boots, with a steel helmet atop each rifle. Two of those memorials were for Chuck Reed and Joseph Jackson, from my Company and Platoon, who had been killed on the September/October mission. The other set was for Thomas Porter, who was also from my Company, and who was killed about three weeks before I joined the Company. While in that formation, we stood at attention and listened to a South Vietnamese officer, as he read the citation awarding our Battalion the Republic of Vietnam Gallantry Cross Unit Citation.

After being in the jungle for what seemed like a small eternity, we had to get re-accustomed to many things we had not seen during that time. Buildings, electric lights, vehicles and other trappings of civilization were good to see again, but were, at first, a little strange since we hadn’t seen them in so long.

A few nights after we returned to the Base Camp a number of us were standing and sitting outside the barracks, drinking beer or sodas and enjoying the night air and sky, and most of all, enjoying not being in the jungle. Our Company area was on a rise called “Highlander Heights” and we looked down and out over the Base Camp. Camp Radcliff was a huge, sprawling affair nestled in the shadow of Hon Con Mountain. As we gazed out across the compound an isolated light on a light pole could be seen here and there, but the Camp was mostly bathed in darkness.

We all watched in silence as two large fiery eyes slowly moved across the compound some distance away. They didn’t move in a continuous straight line but instead snaked their way along, changing direction every so often, and stopping from time to time before continuing. After a couple of minutes without anyone saying anything, someone said “maybe it’s a dragon.” For an instant we all shared the same thought that “yeah, it could be a dragon.” Then, after a moment, someone said “it’s a truck.” We erupted into fits of laughter, all of us laughing at ourselves for not recognizing it as a truck from the start.

We had been in the jungle for what seemed like so long, living a primeval existence, that we had forgotten what a truck looked like as it drove across the base as night. But more importantly, that existence had created in our minds the belief that such things as dragons just might exist.

Vietnamese dragon illustration by Goran tek-en

Used under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en

Copyright © Michael Belis 2020

All rights reserved

Home | Photos | Battles & History | Current |

Rosters & Reports | Medal of Honor | Killed

in Action |

Personnel Locator | Commanders | Station

List | Campaigns |

Honors | Insignia & Memorabilia | 4-42

Artillery | Taps |

What's New | Editorial | Links |