![]() 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry

1st Battalion 22nd Infantry ![]()

An Khê 1970

The 4th Infantry Division goes home

The 4th Infantry Division left Vietnam in Increment V of the U.S. Army withdrawal from the Republic of Vietnam. The official date of the Division’s departure was December 7, 1970. At that time, the Division “went home” and became headquartered at Fort Carson, Colorado. During the month of November 1970 units of the Division began to “disappear” from Camp Radcliff at An Khê, as their administrative functions were either transferred to Fort Carson, and their personnel were rotated back to the United States, or the units were simply inactivated, and their personnel were transferred to other units still in Vietnam.

Three of the thirty-six units that made up the Division did not go to Fort Carson or inactivate when the Division left Vietnam. Those three units were detached from the Division, transferred to direct command by other organizations, and remained behind in Vietnam. The three units were 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry (my Battalion), 1st Squadron 10th Cavalry and 5th Battalion 16th Artillery.

It is difficult to describe what it felt like to be left behind, and not be able to go home, when it appeared the rest of the Division was going home. The first thing that came to mind was what a rotten piece of luck. Why our unit and not some other unit. Another was the idea of the loss of safety in numbers. All together the three remaining units probably totaled about 2000 to 3000 men, where before there had been 10,000 to 15,000 or more. Yet another thing was the knowledge that U.S. troops were being pulled out rapidly, our country was getting out of this war, and we understood that being left behind like this meant any one of us could end up being the last American killed in the war. Of course if a soldier is killed in a war it doesn’t matter if he’s killed at the beginning, the middle or the end, but the distinction of being the last one killed denoted the very worst luck possible.

As it turned out it would be another year before our Battalion left Vietnam and I would personally leave the country some eight months before that happened. The last American ground troops left Vietnam another year after that and the last American to die in country was two years after even that. So I left Vietnam four years before the war ended, thus becoming the last soldier killed in the war never could have been a reality for me, yet still it loomed large in my mind at the time. And the chance of having that dismal kind of luck was unbelievably demoralizing. I was not alone in feeling that way and it was somewhat comforting to realize that most of us shared that concern. About that time a common morbid joke we shared was a play on our Regimental motto which we muttered to each other when the Company Commander or First Sergeant were not within earshot. We looked at each other with a smirk on our face and instead of saying our motto of “Regulars By God” we managed to spit out at each other “Regulars Goddammit.”

Sign at the entrance to

the 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry area at Camp Radcliff 1970,

showing our popular

(though unofficial) Regimental motto of "Regulars By

God".

An Khê late 1970

My Company, Company C, left An Khê by truck convoy with our Battalion on November 1, 1970, bound for Tuy Hòa, where the Battalion would be officially headquartered from December 1970 until it left Vietnam in January 1972. During the month of November 1970 Company C was stationed at Tuy Hòa and Phú Hiêp. In late November Company C and Company A were returned to An Khê to provide security for Camp Radcliff. I don’t remember the exact date of our return to Camp Radcliff, but it was in time for Thanksgiving, as that day I was detailed to K.P. duty in the mess hall. It was the only time I pulled K.P. duty in Vietnam, and I didn’t do much that day, as there were Vietnamese civilian workers doing most of the work.

Not long after we returned to An Khê in November we heard about the Son Tây raid. This was an operation where U.S. Special Forces flew into North Vietnam and attempted the rescue of American prisoners of war thought to be held at the Son Tây prison camp not far from Hanoi. Though the raid was conducted successfully, no prisoners were rescued because they had all been moved to another prison camp previously, a fact unknown to the planners of the raid.

The raid was blasted in the press as a big failure, both on the part of the U.S. Intelligence community, and of the Special Forces themselves. The Special Forces, known as the Green Berets, were considered to be the elite warriors of the U.S. Army, and they looked down on us non-elite Infantry units. Outwardly we joked and laughed about the ineptitude of the famous Green Beret “snake eaters”, in failing to rescue any prisoners. But inwardly we all took great comfort in the knowledge that our military, at the highest level, was willing to try to rescue American POW’s. I wasn’t alone in feeling that, as scared as I was of dying, I was more scared of being captured and taken prisoner, and the hardships and unknown ramifications becoming a prisoner entailed.

Camp Radcliff had been a huge base camp, covering a large section of real estate, sprawled out in the shadow of Hon Con Mountain. As the Division was dismantled, and its units ceased to function, the areas they had occupied at the Camp became deserted, and the whole Camp became transformed. Large sections of the Camp began to take on an air of a “ghost town”. Empty buildings were torn down, and those left standing looked forlorn and derelict. Discarded or broken equipment, refuse and debris littered the landscape. Big patches of wide open space now existed that had once been the scene of barracks areas or bustling activity.

We pulled guard duty in the towers and ground level bunkers on the perimeter line around the Camp. The area immediately outside the perimeter was considered a “free fire zone”, meaning we could shoot at anyone or anything we deemed suspicious in that area. At night we were even encouraged sometimes, to fire sporadically, in order to disrupt any possible undertaking by the enemy. There was a small river which ran near or even through the perimeter, somewhere on the north end of the Camp, and one night one of our Lieutenants joined us in a guard tower near the river. We had a small searchlight in that tower and he thought it would be great fun to shoot into the water and watch the splashes from our gunfire. So for a while that night we had target practice by searchlight, shooting our rifles and the M-60 machine gun we had in the tower.

Any time I was at An Khê, from September 1970 through April 1971 it was always alive with enemy activity. Mostly it was a harassing form of activity, such as a few mortar or rocket rounds being fired into the Camp, or a few bursts of small arms fire, or sappers probing the defenses. Once in a long while an actual attack or penetration by the enemy took place. Just a few months before I was assigned to my Company, sappers infiltrated Camp Radcliff, and destroyed seventeen or eighteen helicopters, as the aircraft sat on the “Golf Course”, the area where the helicopters were parked at the Camp.

I knew that if no enemy activity happened for a couple of days and nights, then I needed to keep my rifle, helmet and flak jacket close at hand, because for sure on the third night something was bound to happen. With most of the 4th Infantry Division gone, and the base defended mostly by support units (except for November/December when our two rifle Companies were brought back from Tuy Hòa), and with no Infantry Battalions out in the surrounding countryside keeping pressure on the enemy, the VC/NVA (Viet Cong/North Vietnamese Army) increased their activities against Camp Radcliff.

Don Dodson, a friend who was there with the 4th Infantry Division's DISCOM (Division Support Command) at the time, came up with an excellent description of Camp Radcliff in late 1970. Don said Camp Radcliff became at that time the VC Sapper Training Academy.

Me in a guard tower at

night at An Khê in late 1970. I’m firing an M-16 rifle on

full automatic, with a bipod attached to it.

Note the empty cartridge cases which can be seen being ejected

from the rifle (in the photo just above the handguard).

On guard duty I was paired a number of times with Dodd “Utah” Owens who I had served with in 3rd Platoon when we were out in the jungle in September/October. Utah and I got on each other’s nerves sometimes, but mostly we got along well. I genuinely liked him and had a lot of respect for him. He had been a hunter for much of his life, knew a lot about guns, and was an excellent shot.

One night Utah and I were detailed together for guard duty in a ground level bunker near the river. The bunker was built of filled sandbags, the walls being two or three bags thick, with an entrance at the rear, a plywood roof elevated off the bunker by beams, and a layer of sandbags on the roof. Sometime during the night the enemy fired at our bunker with a large caliber machine gun. Utah and I were sitting inside the bunker and felt the bullets impact the front of the bunker. After the second burst fired against us, we decided to leave the bunker and get behind it, putting an extra wall of sandbags between us and the enemy’s gun.

There were no enemy soldiers attacking our position, and we did not return fire. We took a few more bursts of fire from out of the darkness, and remained behind the bunker for the rest of the night. We leaned against the back of the bunker with our rifles ready and watched for anyone who might try to infiltrate our position but saw no one. In the morning Utah took his pocket knife and dug quite a number of bullets out of the front wall of the bunker. They were either .50 caliber or .51 caliber, big bullets. Some of the bullets were deformed, but some of them were in really good shape, with a few being in near pristine condition. The sand or soft dirt inside the sandbags kept a lot of them from fragmenting or flattening out. Utah gave me five or six of the bullets, which I kept until I returned home.

I had those bullets in my trouser pocket when I landed with other returning soldiers at the airport in Washington in May 1971, coming home from Vietnam. As we moved into the terminal building there were big signs that told us that if we were caught with any “contraband” material we would go to jail. Among the posted list of “contraband” material on the signs was ammunition and ordnance. There was a large bin where the signs said if we had any such material, we could dump it in the bins and no questions would be asked, but if we proceeded beyond the bin, and were caught with contraband on us we would be prosecuted. Not wanting to take a chance on those bullets preventing me from going immediately home, I tossed the bullets into the bin. (I did keep the AK-47 cartridge which I took from an ammunition cache at the NVA bunker complex where Reed and Jackson from my platoon were killed back in September 1970, and which I was wearing with my dog tags on a chain around my neck inside my shirt. That went home with me and now resides in the collection of the U.S. Army Museum on the base at Fort Polk, Louisiana.)

Top:

Henry Shillings

Bottom left: Mike "Chipmunk" Hernandez

Bottom right: Dodd "Utah" Owens

3rd Platoon Company C 1/22 Infantry Camp Radcliff late 1970

After one night of especially intense enemy probing of the perimeter at the Camp, with exchanges of gunfire between American soldiers inside the wire and enemy soldiers outside the wire, instead of returning to our Company area after guard duty, my platoon was collected the next morning, and directed to make a sweep inside the north section of the Camp. We formed a long “skirmish” line, and moved across the area, working our way from the perimeter to about the middle of the Camp, looking for any enemy soldiers who may have infiltrated and might be hiding inside the Camp.

I was part of a group who came upon a good sized silver Airstream camper/trailer which had been left behind by the Division. There was a small air conditioner mounted in one of its windows, which signified that this camper had belonged to someone important. There was a nearby utility pole, but it was obvious that there no longer was any electricity going from it to the camper. Upon entering the camper we discovered some stationery left behind by the previous occupant. The stationery had no name on it, but had a red flag with a single white star on it at the top of each page, signifying the rank of Brigadier General. I along with several of my buddies, each took some pages of that stationery. I wrote a letter home using it. After my mother died in 2000, among her possessions I found a box of letters she had kept that were written by me while I was in the Army. One of the letters was the one I had written on the General’s stationery.

In the bathroom compartment of the camper there was a flush toilet, an item which most of us had not seen since arriving in Vietnam. The seat lid was down, and we thought it would be great fun to relieve ourselves in the General’s toilet, which would be a story we could tell our grandchildren. When we raised the lid however, we found the toilet half filled with waste already. Obviously others had the same idea before us. We left the camper and continued our sweep across the Camp. We found no enemy soldiers and returned to our barracks.

One day I was called into the office of our Company Commander, Captain Joseph Cinquino. He told me he had reviewed my personnel file, had observed me while we were out on that search and destroy mission in September/October, had spoken with people from my platoon, and he thought I would make a good Sergeant. Battalion Headquarters was convening a review board in a few days to promote a couple of soldiers to Sergeant, and Captain Cinquino wanted me to appear before the board as a candidate for promotion.

I told him I’d think about it. When I got back to my barracks, my new Platoon Leader, First Lieutenant Philip Rosine, came up to me and was really determined that I should go before the board and become a Sergeant. I told him I didn’t want the responsibility and would rather just remain a lesser rank enlisted man. Lieutenant Rosine told me it would mean a boost in pay. I told him I wasn’t going to get rich in the Army. He told me it meant I would never have to pull K.P. duty or burn shit again. That set me to thinking. He told me that it meant I would get out of a lot of the dirty, mundane, aggravating jobs and details that I was doing now, because it would mean that I would be the one telling other guys to do those chores. I think that’s what convinced me and I agreed to go before the promotion board.

Phil Rosine and I then undertook a crash course to teach me answers to questions the board might ask me. I memorized facts and figures, went over lessons I had learned in training, and in general tried to absorb as much knowledge about the Army as I could. He got me a clean uniform that didn’t have any rips or holes in it, and we made sure it had my Specialist 4 rank insignia on its collars. It had a U.S. Army tape on it but didn’t have a name tag. I didn’t have any name tags, and there wasn’t enough time to go find a tailor and have a name tag made, so we took an ink pen and wrote my name on the shirt where the name tag was supposed to go. For the first time since getting to Vietnam I polished and shined my boots. As a final touch Lieutenant Rosine let me borrow his black “Regulars By God” scarf and a fatigue cap that wasn’t all bent out of shape. I had to admit, I looked like a real soldier, almost.

I reported to the shack where the board was being held and went inside. At one end of the room was a bunch of tables placed together to make one long table. Behind it sat seven soldiers, most of them officers, with a Major in the middle. Two of the soldiers were high ranking Sergeants. I recognized none of them. I reported, saluted, and was told to sit in the chair provided for me. They began to ask me questions. None of them looked very happy so I made sure my demeanor was serious and professional, and not the smart aleck bum that I usually was.

They asked me things like … what was the maximum range of an M-60 machine gun, the names of the officers in my chain of command, and other assorted items that Lieutenant Rosine had made me commit to memory, and I rattled off the answers immediately. Then they asked me questions that I had to think about, like … what would I do if this happened, or if that happened, and I tried my best to come up with answers that not only made sense to me, but also would be the kind of answers they were looking for.

Then they started asking me questions about map reading and using a compass. Uh-oh, my weak point. Back in training at Fort Polk, compass and map problems were one thing I had difficulty with. I could read a map pretty good, and find grid coordinates easily enough. But using a compass for anything except determining which way was north, south, east, or west, I was plumb out of luck. One of the officers asked me a question that involved using a compass in ways I did not really understand. I tried to bluff my way through an answer, by mentioning azimuths and back azimuths, degrees, and other terms I knew nothing about, but I could tell they weren’t buying it, and I was showing them that I was a fool when it came to using a compass. Most of the board members had frowns on their faces, and I just knew I was sunk right there and would not be promoted to Sergeant.

Then the Major almost cut me off in mid-answer, looked at me with a stern face, and asked me “how would you find your way to safety if you were separated from your unit?” I knew that I could not answer that question, giving an explanation that involved using a compass to plot azimuths, like he wanted me to. So I gave up and resigned myself to my fate. Stop trying to be somebody you’re not, and be honest, I told myself. I looked at the Major and said “To tell you the truth, Sir, I would use my compass or the sun to determine which way was east and I would head east.” The Major still had a mad look on his face and asked me “why would you head east?”

I answered “because the coast of the South China Sea is to the east, and once I hit the coast I could turn left or right and eventually I would come across an American installation.” The Major stared at me with a blank expression on his face, devoid of any emotion. I thought to myself … we are at An Khê, in the middle of the country, and are a good one hundred miles or more from the coast, and I just told this guy I would walk to the coast! What an idiot I am. Okay, I didn’t want to be a Sergeant anyway.

The high ranking Sergeant seated on the right was looking directly at me and grinning from ear to ear. The high ranking Sergeant seated on the left was looking down, was leaning on his elbow with his hand hiding his brow and appeared to be chuckling to himself. A couple of the officers were making notes. The members of the board asked me some other questions not involving a compass and map reading, thanked me for appearing, and dismissed me.

I went back to my platoon and told the guys I probably blew it with the board and didn’t make Sergeant. A day or so later Lieutenant Rosine came and found me and told me I had passed the board and would be promoted to Sergeant. When I told him how my board appearance went, he laughed, and said my honesty and down to earth answers are probably what impressed them. It was apparent to me that I had bumbled my way into becoming a non-commissioned officer.

Jim Regalia, also from Company C, and I had both passed the board, and we were promoted to Sergeant together in orders dated December 25, 1970, with date of rank back to December 16.

Award

ceremony at Tuy Hòa, either late December 1970 or early January

1971.

At far left is 1st Sergeant Gray. Tall officer with his hand

outstretched is the newly

assigned Commanding Officer of Company C, Captain Arthur Findley.

Yellow arrow

points to me. Captain Findley pinned my Sergeant stripes on

me in this ceremony.

Photo by Tom Porter

Sappers on the bunker line

One night in late 1970 Dodd “Utah” Owens and I were detailed for guard duty for another instance of many times together on the perimeter line at An Khê. This night we were assigned to a guard tower. Inside our tower was an M-2 .50 caliber heavy machine gun, in a fixed pedestal mount at the front center of the tower. Also in the tower was an M-60 medium machine gun, sitting on its buttstock and leaning against a corner inside the tower. Utah and I had each brought our M-16 rifles with us, so we had a lot of potential firepower with us in that tower.

The M2 .50 caliber heavy machine gun was an incredible experience to shoot. Its normal effective range was close to 3,000 yards but it could reach out to as much as 7,000 yards maximum. Tracers loaded every fifth round aided in placing successive shots on targets at some distance away. The gun was highly accurate.

In Infantry training at Fort Polk we did considerable shooting with the weapon. In those days the military’s budget was very high and there was plenty of ammunition available, to do live firing with all of our weapons. When I was at Fort Knox for the Armored Personnel Carrier (APC) driver’s course we also did extensive firing of the weapon. It was the main weapon on the M-113 APC that we were being trained to drive, so we were given a lot of time on the firing range to become accustomed to shooting the gun. Most of the targets we fired at while at Fort Knox were old worn out APC’s. At 1,000 yards away the bullets from the .50 caliber would go through one side of the lightly armored APC and ricochet and bang around inside the vehicle.

The North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong had their own heavy machine gun, the DShK of Soviet manufacture and the Type 54 of Chinese manufacture (both of which we called a .51 caliber, to distinguish them from our .50 caliber gun). In addition to the DShK and Type 54 the communists in Vietnam also used captured examples of our .50 caliber since it was such an excellent weapon.

M-2 .50 caliber machine gun on the kind of mount we had in the tower

Photo by U. S Air Force

The tower we were in that night sat on a rise in elevation, and was flanked by ground level sandbagged bunkers on either side of us. I don’t know who was in those ground bunkers, but for sure they were not members of my platoon. Our tower was a bit of a distance from the rows of barbed wire and razor wire that sat on top of a minefield and was the perimeter line of the Camp. At the wire was a light pole with an electric heavy duty security light mounted on it. The light illuminated the wire, the area just outside the wire, and the area in front of the tower.

That night the enemy sappers apparently chose our section of the perimeter as the location at which to probe for weaknesses in our defenses. A sapper could be more accurately described as a combat engineer/commando. He carried explosive charges, called satchel charges, and his job was to get inside a position, in this case, inside Camp Radcliff, and set off his explosives where they would do the most damage. It was not intended for him to fight his way into a position, but rather to infiltrate his way inside. He could be accompanied by buddies who would provide covering fire for him as he attempted to sneak his way into a position.

The guys in the ground level bunker below us to our left began shooting outside the wire directly to their front. We suspected they had detected enemy movement in front of their bunker, but we had no communication with them, so we didn’t know for sure what was going on. There was no return fire from outside the wire, and for several minutes the guys in the bunker would from time to time fire a burst or two into the darkness. After a short while they were joined by an APC, which pulled up next to their bunker. The APC began firing its .50 caliber machine gun into the dark outside the wire.

Utah and I were watching with much interest the goings on at that bunker. Utah was leaning against the left side of our tower, and appeared to be lost in a bit of a trance, with his focus fixed squarely on the fireworks emanating from our left. I was watching it all too, but kept glancing to our immediate front every twenty seconds or so. One of the times I looked to our front I saw a human form not far outside the wire. It was an almost perfect solid black silhouette of a human being, walking slightly bent over, not straight toward us, but across our front, parallel to the wire.

He must have thought he was outside the circle of light cast by our light on the pole, but I could see him quite plainly. Almost as a reflex, I picked up my rifle, aimed it at him and squeezed the trigger. At the exact place I was aiming, at the exact moment my bullet should have struck, the silhouette exploded with a bright flash and a loud boom. It surprised the hell out of me. I must have hit him right in one of his satchel charges and set the thing off. Utah nearly jumped out of his skin. Since he had been transfixed on the bunker to our left, he had not noticed me pick up my rifle. I had not told him I saw something, or warned him I was about to shoot, so firing my rifle right next to him, which made a loud bang, and the near simultaneous boom of the explosion to our front just about gave him a heart attack.

Utah yelled out a “What the ….” and since I was still shocked by what I was shooting at having exploded, all I could manage to do was to stammer “Well it was….that is… I uh…” Then suddenly a short burst of green tracers came out of the darkness to our front and went right by the side of our tower, accompanied by the simultaneous popping of gunfire. That was followed immediately by a longer burst of huge red/pinkish tracers, seemingly as big as bowling pins, which came from straight to our front, and zoomed right over the top of our tower, cracking loudly as they passed over us.

I grabbed the .50 caliber in the tower and Utah grabbed the M-60 and we both fired into the black night, in the direction from which those huge tracers had come. We both let out pretty long bursts from our guns, then stopped. Another long burst of big red/pinkish tracers came at us, this time lower, and bullets hit just outside the wire, inside the wire, and then on our side of the wire. Some of those tracers ricocheted, some flew up, and some flew off to the sides. One tracer hit on our side of the wire, ricocheted up, and in slow motion arced its way straight into our tower.

Utah and I both “hit the deck.” For just an instant, maybe two or three seconds, we were both flattened out on the floor of the tower, looking at each other, realized what we were doing, and then both jumped up. Neither of us had been hit. We resumed fire with our machine guns, sending more bullets out into the darkness, then paused firing. No return fire came back at us, but for good measure we started shooting again. Utah only got five or six rounds out of his M-60 when it jammed. I got maybe a dozen more rounds out of the 50 when it too jammed and I couldn’t clear the jam. We then picked up our rifles and waited with them pointed to our front. We took no more fire, however, and saw nothing out there. I could not see a body or silhouette on the ground at the place where I had shot and it had exploded.

We watched with apprehension and our hearts still pounding for quite a while, before calming down. On our left, the guys at the ground level bunker fired outside the wire a couple more times. After about an hour, the APC left. Apparently everything was over for the night. Sometime later a guy came from the bunker to our right, to ask what had happened. He was from some aviation unit, a mechanic probably. He had a .38 special revolver in a holster strapped to his hip. He told me he was issued the gun in his unit. I asked him to look at his pistol and he let me examine it. I was mighty impressed with it. The only pistols I had seen in the Army were .45 caliber automatics, and every one of them looked like they had been through several wars. The ones I had fired in training, the ones I had been issued in Germany, and the ones I had seen in Vietnam, all, almost without exception, looked like they were all worn out. That revolver was quite different. Its deep blued parts fitted tight & the cylinder turned with precision, and I wished I had one of those I could stick somewhere on me next time we went back out in the boonies.

The next morning I could see no evidence of anything outside the wire. We were picked up by the truck when our guard shift was over and returned to our barracks. As we sat and relaxed in the barracks Utah was telling the guys about the previous night’s activities. Lieutenant Rosine heard about it and came to ask me what had happened. I explained it all to him, and told him of the silhouette exploding when I shot it. He was excited and asked if I wanted to go outside the wire and look for a body. I told him no. He said “if we find anything there could be a medal in it for you.” I again declined.

At that time I wasn’t interested in medals. The only decoration I cared about was the Combat Infantryman Badge. That badge told the world the wearer of it had been an Infantryman in a shooting war and had performed his job well enough to earn the badge. I had already received that badge and just wasn’t concerned about any other decoration.

And by that time I had developed an attitude of self-preservation. In that attitude I made a rule. I drew a three foot circle around me wherever I was. If something happened outside of that circle I didn’t go to see what it was, unless I absolutely had to, or was ordered to. Actually I would break that rule a number of times. But that morning I didn’t feel like breaking it. That morning I felt that the more I went “outside the wire”, for any reason, the more I cut down on the odds that I would make it home.

Sometimes I regret that decision to not go look for a body. As it turned out, this was the closest I ever came to knowing I had hit somebody I was shooting at. But, had I gone outside the wire, with my luck we probably would not have found anything anyway. The enemy liked to recover the bodies of their dead when they could. All that firing at our tower may have been to protect their recovery efforts and they could have dragged him off at that time. Or they could have dragged this one away in the dark any time later without us seeing them do it. Ultimately I have to be satisfied in the knowledge that I took just enough chances in Vietnam, and did not press my luck to the extent that it prevented me from surviving and coming home. Maybe going outside the wire that morning would have been that one extra time of pushing my luck too far, and I might have had to pay for it at a later date.

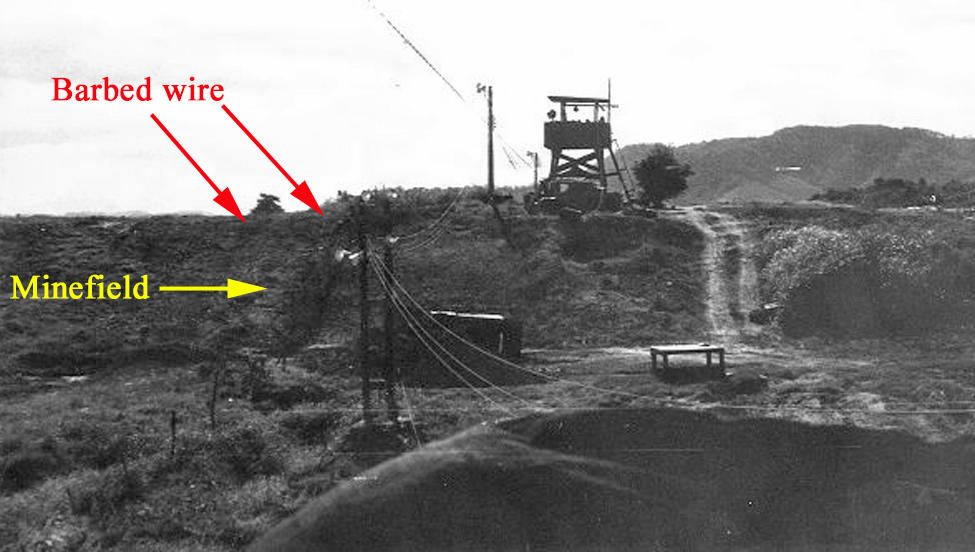

Guard

tower on the perimeter line at An Khê. Photo taken in 1969 or

1970. This tower is very similar to the one Utah and I were in

that night

when the sappers probed our position. The tower itself is exactly

how I remember our tower to be, except that this one has a

searchlight

instead of a .50 caliber machine gun at the front. This tower is

on a rise in elevation, but I remember our tower being on a

higher rise

than this. I also don’t remember light poles being on each

side of the tower like this one. I remember a single light

directly

in front of the tower, and more near the barbed wire than these

lights are.

Photo

by Allan Leigh Winger, 560th Light Equipment Maintenance Company

(Direct Support), An Khê February 1969 - September 1970

Barbed wire and minefield identifications added by Michael Belis.

Original photo from the Chalet

Eagle In Vietnam website

Home | Photos | Battles & History | Current |

Rosters & Reports | Medal of Honor | Killed

in Action |

Personnel Locator | Commanders | Station

List | Campaigns |

Honors | Insignia & Memorabilia | 4-42

Artillery | Taps |

What's New | Editorial | Links |