![]() 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry

1st Battalion 22nd Infantry ![]()

Arrival in the Philippines and the Pasig Expedition 1899

![]()

Campaign Streamer awarded to the 22nd

Infantry for service

during the Pasig Expedition

After the Spanish American War

the 22nd Infantry lost a large number of Soldiers to disease and

end of enlistments.

During the latter part of 1898 the Regiment's ranks were

replenished with a great many new, and for the most part,

raw recruits. A hurried training program was initiated for these

recruits at Fort Crook. How they would perform

in a combat environment as harsh as the Philippines was unknown.

As was later attested to in the Regimental Histories

and after-action reports these new recruits learned quickly, and

aquitted themselves professionally,

adding to the long line of service of the Regiment.

The 22nd Infantry arrived in the

Philippines in the early part of March, 1899, after the defeat of

the Spanish.

US forces held the city of Manila when the Regiment landed there.

War had already been declared by the Filipinos

while the Regiment was still at sea. The Filipino insurgent army,

led by Aguinaldo, was spread out around Manila,

mostly to the north and east of the city. A large body of the

insurgent army was headquartered at Pasig, to the east.

The first campaign of the war mounted by the US against the

insurgency was against those enemy forces at Pasig.

The mission was to either destroy them, or drive them north, so

as to make them link up with Aguinaldo's forces

in the northern part of the island, and therefore create a single

front with which the Americans would have to contend.

Within a week of landing on Philippine soil, the 22nd Infantry became an integral part of that first campaign.

The following article

describes in detail, the loading and departure of the 22nd

Infantry

from San Francisco, for duty in the Philippines, February 1,

1899.

The article is incorrect

when it names Lieutenant Colonel Patterson as being second in

command of the Regiment.

LTC John Patterson was not with the 22nd Infantry at this time.

He was in the process of retiring from the Army,

which he did on February 6, 1899.

Major Leopold O. Parker,

mentioned in the article as being in command of the Army

personnel on the ship Ohio,

was actually second in command of the Regiment at this time.

Article from The San Francisco Call, Wednesday, February 1, 1899

CDNC California Digital Newspaper Collection

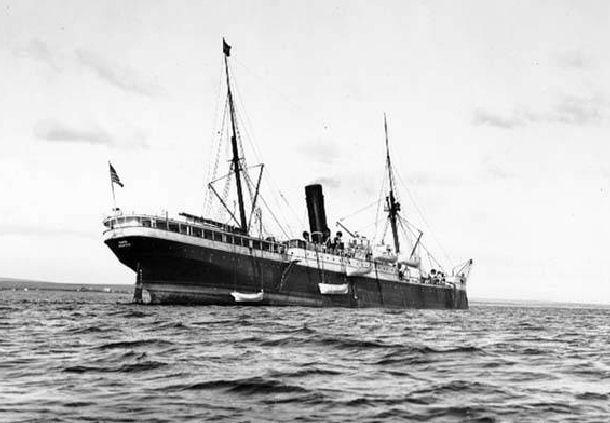

The transport Senator

as she appeared in 1899. The Senator

carried the 22nd Infantry Headquarters, Regimental Band and

Companies A, B, D, H, K and M to the Philippines in 1899.

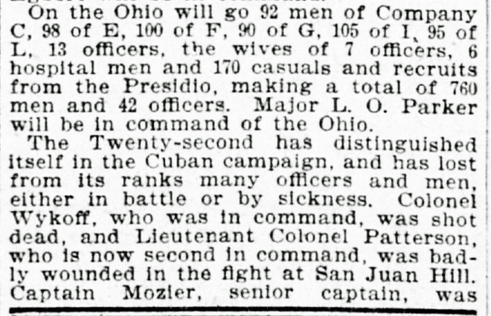

The transport Ohio. The Ohio carried Companies C, E, F, G, I and L to the Philippines in 1899.

Photo from the Poulton Web website

The following narrative is taken from the Regimental histories compiled in 1904 and 1922

Character of the Enemy and Events Leading up to the Insurrection

The 22nd Infantry spent a

comparatively short time in inaction after the close of the

Spanish-American war.

On January 27, 1899, the command left Fort Crook and proceeded by

rail to San Francisco, California,

bound for the Philippines and more adventure. (Ed., The 1st

Battalion left Fort Crook on January 26,

the rest of the Command left the next day, January 27.)

The regiment did not waste much

time in California.

Arriving there January 31, on the following day twenty-six

officers and one thousand and seventy enlisted men

boarded the chartered transports Senator and Ohio and sailed for

our new possessions in the Far East.

The first night at sea an enlisted man was washed overboard and

drowned.

(Ed., The man lost overboard was

Corporal George A. Abbott, of Company D.

In the 1904 Regimental History two other deaths were also

recorded during the voyage. On February 6 Private James T. Larkin

of Company I, and on March 2 Private Clarence R. Overton of

Company G. Both were recorded as "Died of Disease".

Private Overton was a passenger on the Ohio, and actually died of

spinal meningitis, according to newspaper reports of the day.)

The transports stopped at

Honolulu to coal, February 9 to 13. The Senator arrived in Manila

bay March 4; the Ohio March 5.

During the voyage the Filipinos had rebelled against the

authority of the United States and when the 22nd arrived,

Manila, in possession of the Americans, was invested on the land

side by insurgent armies.

The regiment disembarked March 5 and 6, occupied Malate barracks

and equipped for tropical service.

The thatch-roofed barracks at Malate

Photo from the Regimental History of 1904

March 10, Companies B, C, H and

L, were assigned to a position on the line of outposts to the

southwest of San Pedro Macati.

Since shortly after the beginning of hostilities, February 4,

1899, the American line south of the Pasig river

had extended from San Pedro Macati southwesterly to Manila bay.

This line was intrenched and was opposed by insurgent forces

along its entire front. Shots were exchanged daily. Night attacks

by the insurgents were frequent;

the regiment suffered casualties almost as soon as they took

position on the line. (Ed., Wounded in action on March 11 was

Private Marshall Combs of Company B and Private Amos W.

Seigenthaler of Company C.)

Beyond the fact that Pasig City

was an insurgent stronghold and that the smaller towns were

occupied

and levied upon by the Filipino soldiery, little was known of the

strength and position of the enemy.

Aguinaldo, with whose insurrection the 22nd Infantry was now

intimately concerned, was a wily and unscrupulous enemy.

After the destruction of the Spanish fleet in Manila bay the

native leader, under advice of the Hong Kong junta,

proceeded from that city to Manila with the intention of securing

as much aid as possible from the United States,

and then, when sufficiently strong, of driving out the Americans.

His course throughout was consistent with this well-settled

intention. His declaration of independence of June, 1898;

his capture during the succeeding seven months of the weakly

garrisoned posts throughout the islands,

by which he obtained large quantities of arms and ammunition; the

elimination from his so-called government of his able advisers,

who advocated United States supremacy; his declared dictatorship;

the concentration of his troops

and the building of intrenchments and fortifications around

Manila; the public demonstrations and rejoicing at his capital of

Malolos

on the anticipated victory shortly before hostilities were

begun—all occurring in well-timed succession

prove conclusively a predetermined plan of action to place the

islands under Tagalog rule.

Prior to February 4, 1899, the date of the outbreak, all of

Aguinaldo's communications to General Otis—

and these were numerous—professed friendship toward the

United States and manifested great desire to restrain his people

from hostile acts.

January 9, he appointed a commission to confer with one to be

appointed by General Otis, "for the sake of peace",

as he expressed it. On the very same day, with marvelous

duplicity, he issued a proclamation containing instructions

to "the brave soldiers of Sandatahan of Manila''. This

proclamation contained instructions in minute detail for the

waging of treachery and death

upon the Americans, discussed methods of attack and massacre and

urged all manner of deceit

in methods of gaining access to close quarters with American

soldiers for the purpose of surprise onslaughts.

Natives were ordered to dress as women in order to kill

sentinels. Stones, timbers, red-hot iron, heavy furniture,

boiling oil,

water and molasses and rags soaked in oil and lighted were to be

thrown on the Americans from the house-tops.

Native women were to be pressed into service to prepare boiling-

water, molasses and other liquids

to be used against the troops of the United States.

On the 4th of February,

following the proclamation of the insurrecto chief, the first

shot of the war was fired by a Nebraska outpost

at a Filipino soldier who was advancing on our lines and who

refused to halt.

This shot was immediately followed by general firing all along

the line, the Filipinos receiving severe punishment.

Aguinaldo at once issued his declaration of war in a

"general order to the Philippine Army" as follows:

Nine, o'clock, p. M., this

date, I received from Caloocan station a message communicated to

me

that the American forces, without prior notification or any just

motive, attacked our camp

at San Juan del Monte and our forces garrisoning the blockhouse

around the outskirts of Manila,

causing losses among our soldiers, who in view of this unexpected

aggression and of the decided attack of the aggressors,

were obliged to defend themselves until the firing became general

all along the line.

No one can deplore more than I this rupture of hostilities. I

have a clear conscience that I have endeavored to avoid it

at all costs, using all my efforts to preserve friendship with

the army of occupation at the cost of not a few humiliations

and many sacrificed rights. But it is my unavoidable duty to

maintain the integrity of the national honor

and that of the army so unjustly attacked by those who, posing as

our friends and liberators, attempt to dominate us

in place of Spaniards, as is shown by the grievances enumerated

in my manifest of January 8,

last; such as the continued outrages and violent exactions

committed against the people of Manila,

the useless conferences, and all my frustrated efforts in favor

of peace and concord.

Summoned by this unexpected provocation, urged by the duties

imposed upon me by honor and patriotism

and for the defense of the nation entrusted to me, calling on God

as a witness of my good faith and uprightness of my

intention———

I order and command :

1.—Peace and friendly relations between the Philippine

forces and the American forces of occupation are broken,

and the latter will be treated as enemies, with the limits

prescribed by the laws of war.

2.—American soldiers who may be captured by the Philippine

forces will be treated as prisoners of war.

3.—This proclamation shall be communicated to the accredited

consuls of Manila, and to congress,

in order that it may accord the suspension of the constitutional

guarantees and the resulting declaration of war.

Given at Malolos, February 4, 1899.

(Sgd) EMILIO AGUINALDO,

General-in-Chief.

The following day Aguinaldo

issued another manifesto addressed to the Philippine people

in which he disclaimed all responsibility for the rupture,

placing all the blame on the Americans

and assuring the natives that they could resist the occupation as

long as they wanted to.

The following day Aguinaldo issued instructions marked with the

most savage ferocity.

For the sake of independence, all Americans—men, women and

children—were to be massacred.

For policy's sake, English, French and Germans, their lives and

their property, were to be spared.

But for oriental greed's sake, all Chinamen were to be put to the

sword;

to appease the wily chieftain's half barbarous army, the property

of Chinamen was to be subject to loot.

If these acts had been carried into execution, justification

undoubtedly would have been made

in extravagantly worded phrases prating of liberty. Fortunately,

American arms prevented the wholesale slaughter.

Such was the character of the enemy the regiment was to oppose.

Added to this duplicity

were arms and munitions of war in great abundance. The terrain of

the country, superbly suited to check the American advance,

afforded additional advantage. That our forces never suffered

reverses in the islands in no way proves that the Filipinos were

poor fighters.

Ed. note: The preceding

paragraphs are taken from the 1922 Regimental history, and are a

condensation and summary

of three proclamations issued by Aguinaldo on January 9, and

February 4 and 5, 1899. In the 1904 Regimental history all three

of these proclamations are printed in full, and take up nearly

five pages of the book. The January 9 proclamation

gruesomely details Aguinaldo's instructions to the

"Sandatahan of Manila", as he called his army, in

prescribing

methods of attacks upon and ways to kill Americans and Filipinos

who sympathized with Americans.

Some of Aguinaldo's Katipuneros

(Katipunan soldiers), wearing captured Spanish uniforms.

The Katipunan Society had been formed as a secret society to

resist and fight Spanish occupation.

When Aguinaldo declared war on the Americans he assimilated

Katipunan forces into his army.

A Filipino flag can be seen in the right center of the photo,

with its distinctive "Sun" emblem,

the design of which evolved directly from previous Katipunan

flags.

This "Sun"emblem of the Katipunans would, in 1923, be

incorporated into the heraldic design

of the Coat-of-Arms and Distinctive Unit Insignia of the 22nd

Infantry.

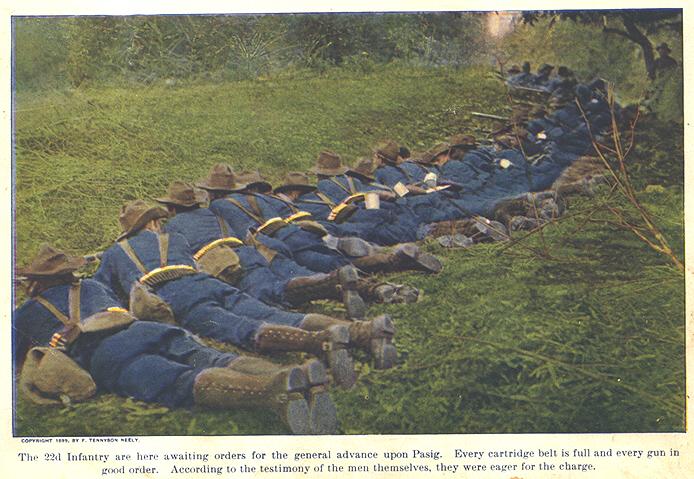

Illustration from a

period book showing the 22nd Infantry at Pasig.

The black & white photo has been color tinted, and the artist

has incorrectly

given the Soldiers blue uniforms.

Photo from:

A Wonderful Reproduction of LIVING SCENES In Natural Color Photos fo America's New Posssessions.

F. Tennyson Neely. New York, Chicago, London: 1899

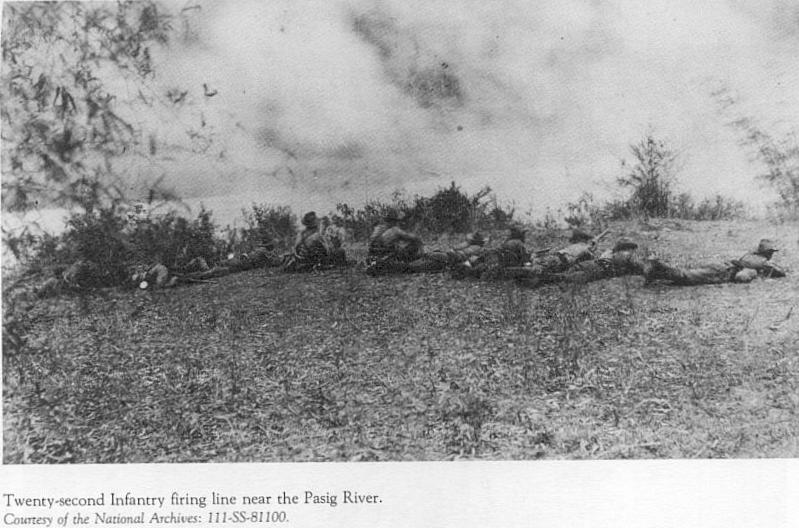

Section of the same

photo as above, but in the original black & white.

The tan or khaki color of their uniforms can be plainly seen;

had the uniforms been blue, (as the artist in the preceding photo

has portrayed them)

then in the black & white photo the uniforms would be darker

than the men's campaign hats.

The Pasig Expedition

Brigadier-General Loyd Wheaton,

commanding.

Troops Engaged:

Provisional Brigade consisting of:

20th Infantry; 22nd Infantry; two battalions 1st Washington

Volunteer Infantry; seven companies 2nd Oregon Volunteer

Infantry;

one platoon 6th Artillery, and three troops 4th Cavalry.

The Pasig expedition was the

first organized campaign against the insurgents, General

Wheaton's instructions being

to drive the enemy beyond the Pasig, "striking him wherever

found".

The night of March 12 the brigade was formed and bivouacked in

line in rear of entrenchments

extending from San Pedro Macati toward the bay. The 22nd Infantry

formed the right of the infantry line;

on the extreme right was a squadron of the 4th Cavalry.

Soldiers of the 2nd

Oregon Volunteers prepare to fire a volley during the fight at

Pasig.

They are armed with the 45-70 caliber "trapdoor"

Springfield rifles. The 2nd Oregon

was part of BG Wheaton's Provisional Brigade alongside the 22nd

Infantry.

Captain Jacob Kreps, in command of Company M, 22nd Infantry, wrote of the night of March 12 :

"Rain

started to fall before we reached our destination. Company M

Passed a sister regiment—

the men standing on one foot, then the other, attempting to keep

dry—while, at the same time,

trying to keep a fire going and fry bacon.

After trudging

across several muddy rice fields, we took our position a few

hundred yards

to the rear of the trenches. A short distance beyond, was a

church occupied by an Oregon detachment.

The rain kept

up, more or less, all during the night. Everyone was

miserable—

especially the new recruits who were getting their first taste of

field service. Many of the men were without cover.

Very few took the trouble to put up their shelter

tents—preferring to have the canvas between themselves and

the ground—

rather than between their bodies and the sky. However, I can't

blame them.

In a Philippine rainstorm, a shelter tent gives about as much

protection as an equal size piece of wire netting." * 1

At six o'clock on the morning of

March 13 the brigade moved forward by echelon from the right,

the 22nd Infantry and the 4th Cavalry moving first. In front of

the regiment's position, the country was rough and broken;

trees and stumps of bamboo prevented extended vision; a series of

low ridges afforded the insurgents many superior positions.

From these hidden positions the enemy at once opened with long

range fire, to which it was impossible to reply;

for a time the regiment advanced under fire and in absolute

ignorance of the whereabouts of the insurgent strongholds.

"The

rookies of Company M heard a whistling noise and glanced

curiously at each other—

wondering if it was the sound of a lizard or some other animal.

Then another whistle—and the men quickly realized

that they were hearing their first hostile bullets. Heads

dodged—soldiers darted for the nearest cover and hugged the

ground.

They later

discovered, that if a bullet had time to sing a solo, it would be

distant—too far away to do any harm.

However, if it passed with a zip—a tree, mudbank, or stone

wall were handy bulwarks to have around.

The vicious pellets were never alone—they always had

companions following them."*

2

Shortly after the beginning of

the engagement the squadron of the 4th Cavalry was detached from

the line

and ordered to make a wide detour toward the Pasig River, to

intercept the insurgents' possible retreat in that direction ;

afterward Companies I and A of the regiment were sent to assist

the cavalry. Meanwhile the brigade had forced the enemy

from a strongly-intrenched and fortified position on Guadalupe

ridge. As the advance continued, the insurgents fell back,

fighting stubbornly until they reached the river, which they

crossed in disorder, receiving severe losses.

"We came

upon seven Filipinos on the riverbank. They all surrendered exept

one plucky fellow.

He threw his gun in the river and plunged in himself. Although

the water around him was churned by bullets,

I believe he succeeded in escaping." *

3

Meeting no further opposition at

this point, the brigade occupied the Pasig road, moved eastward

and encountered heavy fire from the Pasig intrenchments. Captain

Kreps was given command of D Company

in addition to M Company and ordered to clear the road:

"We crept

forward, slowly and carefully—rifles at the ready. A grove

of trees and banana plants soon obstructed our view—

but also hid us from the rebels. The trail suddenly curved

sharply, and for about a hundred yards the roadway was cut

through

a hill of solid rock. The stone walls rose thirty feet on both

sides of the path. At the far end of the gorge, the curve

straightened out

and came into full view of the opposite bank.

I decided to

take a few men and investigate. We sneaked through the cut until

I noticed the enemy positions

across the river. The Insurgent trenches controlled this part of

the road—and we soon discovered that they were manned by

sharpshooters.

My troops were spotted, and several straw hats popped into view

above the enemy earthworks.

Each hat represented a puff of smoke—a bang—then the

splatter of a bullet on the rock wall.

We quickly ran

for cover—out of sight from the enemy riflemen. That is, all

except Private William Reinhardt.

Several times the youngster stepped out into the middle of the

road—deliberately knelt, aimed, and fired—

then dashed back to the tunnel to reload. He tried this once too

often and was shot in the foot." *

4

The regiment moved farther to

the east and occupied high ground opposite the town.

From this position a destructive fire was opened on the insurgent

trenches. The armored gunboat Laguna de Bay was sent up

the river

to aid in the attack on the trenches. When the fire from these

trenches had been partly silenced,

the brigade charged the town, routing the enemy and inflicting

great losses upon them.

During this part of the engagement, Companies A and I, a mile

east of the main body, became seriously engaged

with a large body of retreating insurgents. Companies D, E, G and

M advanced to assist the two companies

and drove the enemy beyond Pateros, in the direction of Taguig.

Later in the day a number of insurgent sharpshooters returned to

Pateros,

and until long after dark kept up an annoying fire on the six

companies, whose position upon the river bank was entirely

exposed.

Ed., Killed in action on March 13 were:

Private George E. Stewart,

Company B,

-Private

Wesley J. Hennessy, Company D,

--Corporal

Wynne P. Munson, Company K.

Wounded in Action on March 13 were:

Private Daniel W. Carroll,

Company A--

Private John Mulvahill, Company D-----

Private William M. Harmon, Company D

Private William S. O'Brien, Company D-

Private Joseph Hoffman, Company E----

Private Joseph B. Cox, Company E-----

Private Theodore Misner, Company F---

Private John Blazek, Company I---------

Corporal James Comerford, Company M

Private William M. Reinhart, Company M

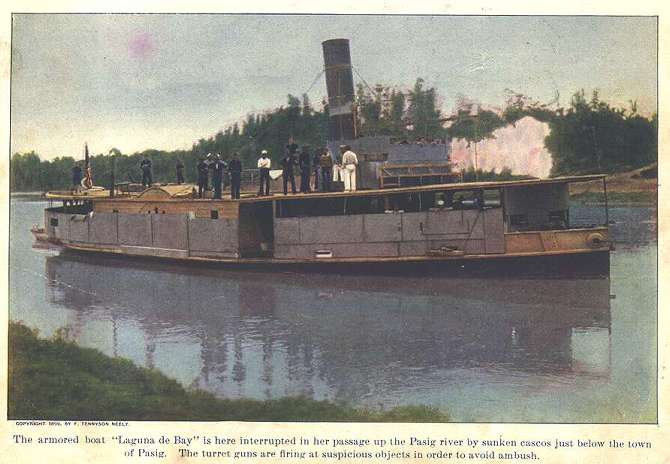

Laguna de Bay on the Pasig river.

A wooden vessel, her sides and bridge were protected by iron

plates.

This gunboat was instrumental in driving the insurgents from the

trenches around the town of Pasig.

Photo from:

A Wonderful Reproduction of LIVING SCENES

In Natural Color Photos fo America's New Posssessions.

F. Tennyson Neely. New York, Chicago, London: 1899

On the morning of the 14th the

remainder of the regiment was placed in position opposite

Pateros.

Here it remained on outpost until March 18. During this period,

the hardships of Philippine campaigning were first felt.

Heavy rains fell nightly during the week; shelter halves gave

little protection; toward morning officers and men,

drenched and shivering, were compelled to rise from their muddy

beds on the ground and sit around camp fires

until the sun finally appeared and dried the clothes on their

backs.

March 18 a force of the enemy

appeared near Taguig and Companies D, E, G and M were sent out to

locate them.

At about 3 o'clock in the afternoon the four companies found the

insurgents, 800 strong, occupying ridges west of Taguig,

and at once engaged them in one of the most spirited combats of

the war. The insurgents, from superior positions

and greatly outnumbering the battalion of the 22nd, fought until

darkness ended the engagement. During the battle

a Company of Washington Volunteers was pinned down by the

insurgents established on one of the ridges. Captain Kreps wrote:

"About

three o'clock, our depleted battalion was placed under the

command of Captain Frank Jones.

We were ordered to move out and attempt to rescue the besieged

company. However, our directive stated for us to proceed

down to the river and move forward along the bank. I protested

and asked permission to advance across the high ground.

General Wheaton denied my request. I considered his order

irresponsible. It would have been much safer advancing along the

ridge.

As it was, we could—and did—head into a trap.

Companies D, E,

and G formed the front line of the battalion with Company M in

reserve. After marching two miles, firing was heard.

We could make out the Washington outfit delivering

volleys—but there was no sign of the enemy.

Scouts suddenly brought word that there were about eight hundred

Insurgents to our front. I hoped that the size of the rebel force

was exaggerated—if correct, we were outnumbered four to one.

As we pushed on

ahead, the terrain became rough and rockstrewn— then cliffs

emerged on our right and left flanks.

Within a few minutes we found ourselves cornered in a horseshoe

shaped depression. High ground surrounded us on all sides—

except at the narrow entrance to the shoe. The lead companies had

proceeded about five hundred yards when the 'music' began.

A hailstorm of Mauser bullets rained down on the troops. Further

progress was impossible. The men dashed for cover

and commenced firing back at the enemy. But our front line was

suffering heavy casualties and ammunition was beginning to run

short.

Captain Jones

shouted orders for the battalion to retreat from the trap, and

directed Company M to protect the withdrawal.

However, the sudden wild, disorganized rush of men descended upon

my troops so rapidly that our company became intermingled

with the returning firing line. There was a great deal of

confusion as the retiring soldiers crowded through the narrow

opening

of the horseshoe—while, at the same time, we were trying to

move past them to the front. During the melee, Jones was shot

and I assumed command of the battalion.

It was a

madhouse of frustration. We were afraid to fire at the Filipinos

for fear of hitting our own troops

as they attempted to flee the trap. Meanwhile, Insurgent bullets

pelted down on us in a pitiless shower. Three of my men were

shot,

including Henry Johnson. I was finally able to reform Company M

as a line of skirmishers, and began a rapid fire assault

on the enemy positions. By the time that the rest of the

battalion was clear of the horseshoe, the Filipinos began to

retreat.

In a little over an hour, our battalion had lost twenty men—

killed or wounded. * 5

Ed., In Combat Diary A.B. Feuer sets the scene next, as Jacob Kreps writes down his feelings after a hard day of fighting:

"It was

nearly dark when the soldiers of Company M returned to their

tents. The sun had set, and a full moon looked down

upon the litter bearers hauling the dead and wounded from the

battlefield. The long line of stretchers—stopping every few

minutes

to change carriers— dragged its slow course back to camp.

Jacob Kreps was tired, bitter, and depressed after the furious

battle,

and he eloquently expressed his feelings in the pages of his

notebook:

'I searched the

hospital tents until I located Johnson. An enemy bullet had

entered just over the left eye and passed completely

through his head. The youngster never regained consciousness.

Johnson's brief service in the Army of the United States was

over—

but his dedication will not be soon forgotten.

The history of a soldier in the regular army, or any soldier for that matter, is the story of his organization while he is affiliated with it.

The hero is

usually of newspaper manufacture—and remains a hero for

possibly three editions. The soldier who falls in combat

needs no such notoriety. If his company or regiment never

disgraces its flag— but only adds to the brightness of its

colors—

this honor is shared with his comrades.

However, what

good is honor to Johnson now? His body lies on the island of

Luzon—sacrificed to a policy

not to be criticized by the soldier, but which has as its

objective the subjugation of a people fighting for their liberty.

Henry Johnson

died—not in defense of his country—but rather because

duty summoned him to that rugged,

rocky spot near Laguna de Bay where the messenger of death was

waiting. No sentiment nor feelings motivated his actions—

only the stern obligation to flag and country, ready to meet any

foe, domestic or foreign. Ready to obey the legal orders of his

superiors.

This is, and always will be, the function of the 'regular

soldier.'" * 6

The battalion lost nineteen men

killed and wounded; among the wounded Captain Frank B. Jones, the

battalion commander.

At daylight on the following day the brigade was deployed facing

toward the south, the regiment occupying the right of the line.

Wheeling on the left as a pivot, the brigade struck the

insurgents south of Taguig, routed them, and drove them down the

lake.

The regiment marched twelve miles in extended order during the

swinging movement. The heat was intense;

on the return march the command suffered severely; men dropped

from exhaustion and were brought in by comrades

whose condition was but little better. Near Taguig was seen

ghastly evidence of the previous day's engagements—

many corpses in insurgent uniforms. Considering the extreme care

exercised by the Filipinos in removing their dead,

the number thus left upon the field showed the great losses

Captain Jones' battalion had inflicted.

March 20, orders were received

from Manila disbanding the provisional brigade and ordering the

troops to return to Manila.

The object of the expedition had been thoroughly accomplished. In

the week's campaign, every position occupied by the enemy

in the territory assigned to the brigade had been attacked and

captured; the insurgent forces had been dispersed and

demoralized.

General Wheaton reported Aguinaldo's loss in killed, wounded and

captured as 2,500.

Ed., Killed in Action on March 18 were:

Private John Smith, Company E

------------Private Charles W. Fredericks, Company E

---------Private Henry W. Johnson, Company M

Wounded in Action on March 18 were:

Captain Frank B. Jones, -------

------Private

Berry H. Young, Company D

----Private

Nels Arvidson, Company D

--Private

Frank Yount, Company D

-Private

William Ellis, Company E

----Private

Leander Mings, Company E

-----Private

Carl Crumpholz, Company E

-------Private Charles E. Palmer, Company E

-Private

Robert Rice, Company E

---Private

Merritt Porter, Company E

------Private

Raleigh T. White, Company E

-------Private George Schneider, Company E

--Private

Frank Rurfer, Company G

-------Private Charles E. Halley, Company G

---Private

Earl Edwards, Company K

----------Corporal Edward F. Wilson, Company M

Wounded in Action on March 19 was:

------Private August Schmidt, Company K

Photo of 22nd Infantry Soldiers during

the fight at Pasig.

This photo originally appeared in the 1904 Regimental history.

**********************

The above narrative is taken from the Regimental Histories of 1904 and 1922, except:

* From the book: Combat Diary EPISODES FROM THE

HISTORY OF THE

TWENTY-SECOND REGIMENT, 1866-1905

by A. B. Feuer

Praeger Publishers, New York, N.Y.

* 1 Combat Diary, pp 87-89

* 2 Combat Diary, pp 89-90

* 3 Combat Diary, p 90-----

* 4 Combat Diary, p 91-----

* 5 Combat Diary, pp 93-94

* 6 Combat Diary, p 94-----

Additional comments by the website editor.

Home | Photos | Battles & History | Current |

Rosters & Reports | Medal of Honor | Killed

in Action |

Personnel Locator | Commanders | Station

List | Campaigns |

Honors | Insignia & Memorabilia | 4-42

Artillery | Taps |

What's New | Editorial | Links |