![]() 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry

1st Battalion 22nd Infantry ![]()

The 22nd Infantry in the Malolos Campaign 1899

Part One

![]()

Campaign Streamer awarded to the 22nd

Infantry Regiment

for its service during the Malolos Campaign

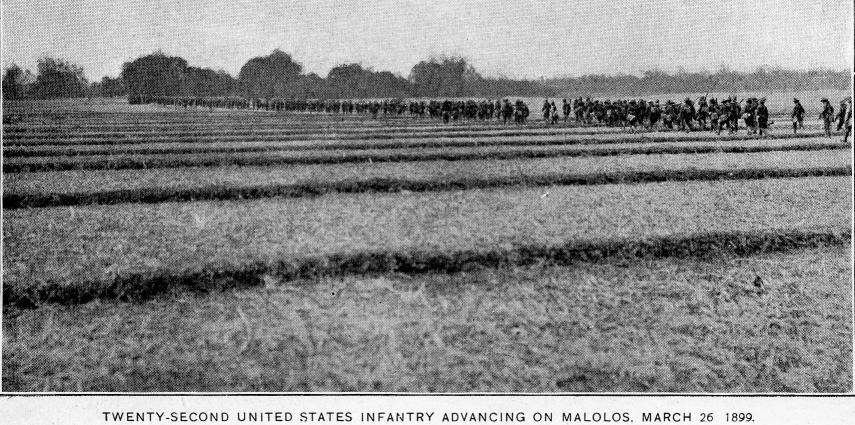

The 22nd Infantry advancing across rice

paddies toward Malolos

Photo from the 1904 Regimental History

(Ed.) Malolos was the headquarters and seat of

power for the First Philippine Republic.

It was here that Aguinaldo convened the first Philippine Congress

and declared the Philippines to be

an independent Republic. As it became clear the United States

wanted the Philippines as US possessions,

Aguinaldo declared war upon the US. His army was spread out

between Manila and Malolos and consisted of between

20,000 to 30,000 soldiers. Commanding the forces sent against

this army was MG Arthur MacArthur,

who, with four brigades of US Army Soldiers, had approximately

12,000 troops for the expedition.

Also at MacArthur's disposal were elements of the US Navy's

Pacific Fleet, to provide gunfire support

from their positions along the coast of Manila Bay. All units

involved were engaged in direct fighting,

and contributed to the overall success of the mission; however,

this account will focus on the 22nd Infantry.

The following narrative is taken from the 1904 Regimental History.

THE MALOLOS EXPEDITION

Major General Arthur MacArthur, commanding.

Troops engaged:

2nd division, 8th army corps, consisting of:

1st brigade, Brigadier General H. G. Otis—two battalions 3rd

artillery; 20th Kansas volunteer infantry; 1st Montana volunteer

infantry.

2nd brigade, Brigadier General Irving Hale—1st Colorado

volunteer infantry; 1st Nebraska volunteer infantry;

1st South Dakota volunteer infantry; l0th Pennsylvania volunteer

infantry.

3rd brigade, Brigadier General R. H. Hall—4th infantry; one

battalion 17th infantry; 13th Minnesota volunteer infantry;

1st Wyoming volunteer infantry.

Cavalry—one squadron 4th cavalry.

Artillery—one battalion Utah light artillery.

Attached to 2nd division:

3rd brigade, 1st division, 8th army corps, Brigadier General Loyd

Wheaton—22nd infantry, one battalion 3rd

infantry;

eleven companies 2nd Oregon volunteer infantry.

|

Major General Elwell S. Otis As a Lieutenant Colonel, Otis

had served eleven years Original illustration from The

Story of Two Wars, |

The object of the campaign was the capture of

Malolos, the insurgent capital.

Shortly after the beginning of hostilities, the 2nd division, 8th

army corps, operating north of Manila, occupied a line of

trenches from Caloocan

to the pumping station near Santolan. On the night of March 24,

the 3rd brigade, 1st division, was attached to the 2nd division,

and under cover of darkness relieved the 1st brigade, 2nd

division, which at once moved and occupied trenches to the right

of its original position.

Insurgent forces were massed along the eight miles of front of

the American line. The greater part of them had never been under

American fire—

their morale was excellent; by extravagantly-worded proclamations

of their leaders, enthusiasm had been worked up to the highest

point;

the equipment of their infantry was good; the supply of

ammunition unlimited.

The plan of campaign, as published in orders,

was as follows: Wheaton's brigade, the left of the line, to

maintain a watching attitude

toward the insurgent line in its immediate front and toward

Malabon, moving forward if the enemy began a retrograde movement;

Hall's brigade, the right of the line, to remain in reserve, the

attached troops to make demonstrations in the direction of the

Mariquina road;

the two central brigades to move forward and to execute a change

of front to the left near Polo; further progress to be determined

by the result and character of the antecedent contest.

The 22nd infantry, in brigade, moved to its

assigned position and relieved the Montana volunteers on the

night of March 24.

The insurgents, occupying lines about 1000 yards distant, were in

high spirit. During the night, they sang, danced, cheered,

and volleyed the American line, which, by order, did not return

the fire. Emboldened by this, the insurgents displayed a bravery

and effrontery

never afterward equalled. Bonfires blazed along their lines.

Around these they freely exposed themselves; in chorus they

yelled taunts and insults

to the Americans; their bugles played our calls; their voices

imitated our commands.

The advance of General MacArthur's command

began at daylight, March 25, as planned. Shortly after the left

center brigade moved out,

General Wheaton ordered the 3rd battalion of the 22nd forward in

echelon to protect the left flank of the brigade; at 8:30 a. m.,

the remaining battalions of the regiment advanced. The insurgents

were found in great force in their trenches, and at once opened

with heavy fire,

to which the American line replied. Soon the firing was

continuous along the many miles of front of the opposing armies.

For a time, the insurgent fire,

delivered from protecting trenches, was accurate and incessant;

as the American lines advanced, this fire decreased in volume and

deadly effect;

rifles were dropped in the trenches or fired, unaimed, high over

the heads of the advancing Americans. In marked contrast was the

fire of our line—

ever stronger, despite casualties, as the line advanced; ever

more accurate as the enemy offered better targets.

Before half of the space separating the

opposing lines of trenches had been traversed by our line, the

insurgents abandoned their trenches

and began a retreat. The terrain was such that they were able to

make many stands under protection or in concealment; from these

positions they fired,

at first rapidly and with effect, afterward with less vigor and

with less accuracy. Despite advantage of intrenched position,

they could not withstand

the uninterrupted advance of our lines; American methods of

warfare did not permit hours of fighting from intrenched

positions

and without loss to either combatant. Beyond the insurgent

trenches, dense jungles of bamboo and many Filipino strongholds

along the extended front caused the advance to become a series of

detached combats. In front of the 22nd, the enemy were driven

back

from line after line of their works; they retreated stubbornly,

taking advantage of all natural obstacles of the terrain, and

abandoning positions

only after severe losses.

By 11:30 a. m., the insurgents in front of

Wheaton's brigade were forced back to trenches beyond the

Tuliajan river.

Their position at this point was very strong, successive lines of

trenches on rising ground. By command, the brigade bivouacked in

its position

south of the river, in order to allow the right of the division

time for its swinging movement. During the remainder of the day,

the insurgents kept up a continuous, long range fire on the

regiment.

Wounded in action, March 25, 1899:

1st Lieutenant Harold L.

Jackson; Private Edward B. Miller, company B;

Privates George C. Richards and Nicholas Gearin, company D;

Private William Meyer, company F;

Private Bert E. Clough, company G;

Sergeant Albert E. Axt and Private Fritz Herter, company H;

Musician Spurgeon A. Cain, company K;

Private Morton R. Hunsicker, company L;

Privates Edward F. Lammers and Louis T. Skillman, company M;

Sergeant LaVergne L. Gregg, company M.

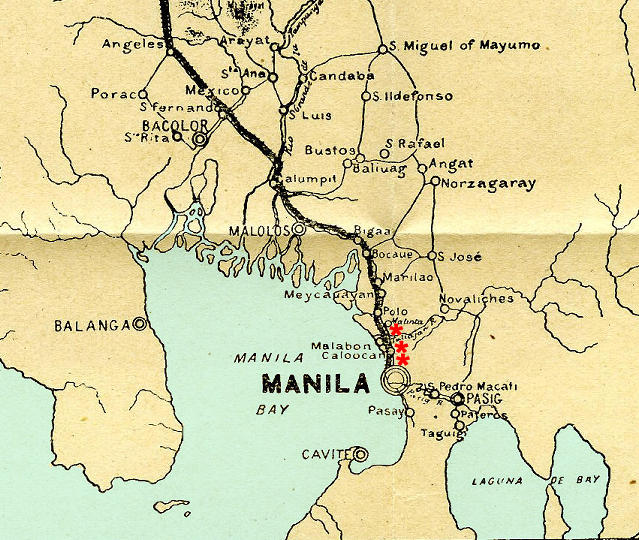

Above is a portion of a map from the

1904 Regimental History (colorized by the editor)

The march to Malolos proceeded along the railroad (the heavy

black line heading north from Manila).

The red marks are the major engagements of the 22nd Infantry,

starting with Caloocan, then Malabon

and finally across the Tuliajan River at Malinta, where the

Regimental Commander, COL Egbert, was killed.

Owing to the impossibility of maneuvering the

long line of the division over the immense jungles, it was

apparent during the first day's fighting

that the strategical plans formulated could not be carried out.

Although the enemy's center had been broken, it was impossible to

advance sufficiently rapidly

to envelope to the west the main fraction of his army thus cut

off. Reconnaissances made early on the 26th showed that the only

road available

for artillery and wagon trains passed through Malinta, which was

in the immediate front of the 22nd. To meet these changed

conditions,

the two central brigades of the division were ordered to change

front on Malinta, instead of on Polo, as originally planned.

Early in the morning of the 26th, the enemy in front of Wheaton's

brigade were in retreat. Malabon, on the left front, was in

flames;

a stream of insurgent soldiers and natives of the country was

pouring north. The 22nd marched a short distance to the right of

where it had bivouacked,

received the fire of the insurgent rear guard, forded the

Tuliajan river, and formed line perpendicular to the river in

order to flank the enemy's trenches.

Advancing to the railroad, these trenches were found deserted.

The regiment changed front to the north; the

first battalion moved forward to scout toward Malinta. On

commanding ground,

800 yards south of Malinta, the insurgents were strongly

intrenched; these works were charged and captured. Five hundred

yards beyond

was a stone church; a breast-high stone wall surrounding the

church bristled with Mauser rifles; here the rear guard of the

retreating insurgent army

hoped to check the American advance. The ground in front of this

stronghold was a natural glacis, broken with only a few rice

paddies;

each seventy meters of the approach was marked with nipa

streamers flying from tall bamboos. A galling fire, accurately

delivered by a superior force,

met the battalion and forced it to seek the shelter of the

captured trenches and rice paddies. Return volleys directed at

the crest of the stone wall

seemed only to increase the intensity of the insurgent fire.

Meanwhile the remainder of the regiment was racing from the rear

to assist the troops

so sorely pressed. Arriving on the line, they threw themselves on

the ground, and at once poured over the stone walls a fire so

accurate

that the well-directed firing of the insurgents promptly ceased.

There was no diminution of their fire—merely less accuracy

in their aim.

During this stage of the engagement, Colonel Egbert, the gallant

commander of the regiment, was mortally wounded.

(Ed., Some accounts portray Colonel Harry

Egbert as having been killed while leading a bayonet charge upon

the Insurgent forces' defensive positions

in and around the church at Malinta. The Regimental histories

make no mention of this bayonet charge. Major L.O. Parker's

after-action report states that Colonel Egbert was mortally

wounded just after the capture of the enemy positions at Malinta.

There is no doubt that Colonel Egbert was the kind of commander

who led from the front, and exposed himself to enemy fire

consistenly;

as a Lieutenant Colonel commanding the 6th Infantry in Cuba, he

was wounded, being "shot through the body" at the

Battle of El Caney,

an engagement in which the 22nd Infantry also fought.)

For twenty minutes the fusillade from both

lines continued. At the end of that time, the insurgent fire

slackened; ten minutes later it ceased.

Entering Malinta, great quantities of loaded and empty rifle

shells were found behind the stone walls of the church; only

artillery

could have forced a valiant enemy from this position. A part of

Otis' brigade completed its change of front and entered Malinta

simultaneously

with the 22nd. It: had taken, however, no part in the capture of

this stronghold. On the night of March 26, the regiment

bivouacked at Malinta.

Killed in action, March 26, 1899:

Colonel Harry C. Egbert;

Private John Miller, company I;

1st Sergeant Charles F. Brooke, company L.

Wounded in action, March 26, 1899:

Privates William E. Geyer

and Harry J.Scanlau, company A;

1st Sergeant Patrick J. Byrne, company B;

Privates Fred W. Arndt and William Howard, company E;

1st Sergeant Ole Waloe, company F;

Artificer John A. Hogeboom, company I;

Private William Dunlap, company L.

|

A commemorative

button made during the period |

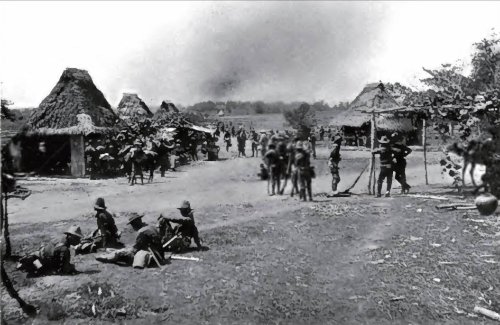

American Soldiers at Malinta, March 26, 1899

March 27, Wheaton's brigade was detached from

the 2nd division, 8th army corps, and detailed to guard the

railroad

and preserve communication with Manila. The network of unfordable

streams between Manila and Malolos necessitated the seizure

of the railroad bridges before the insurgents could destroy them.

A rapid advance, unimpeded with wagon trains, became of primary

importance.

On this day, the regiment marched to Meycauayan; March 28, to the

San Marco river; March 29, to near Bigaa, companies D, E, G, and

M

being left on the San Marco river to guard the division wagon

train; March 30, near Guiguinto.

At Malolos, a desperate resistance was

expected. Friendly natives reported that the insurgents were

prepared to defend their capital

as a political necessity; reconnaissance disclosed formidable

field works, well filled with men. On the American side,

preparations were made

for a battle of considerable proportions. Five battalions of

regular troops, including the 1st and 3rd battalions of the 22nd,

were brought

from their positions along the line of communications to the

front, to be placed in support of the main fighting line.

At 7:00 a. m., March 31, the attack was begun

with artillery. Fifteen minutes later, the Nebraskas, on the

extreme right of the line, advanced.

At 7:20, the South Dakotas, second from the right, moved out; at

7:25, the next regiment from the right, the Pennsylvanias, moved

forward.

These movements were followed by the direct advance of the

remainder of the battle line, giving the line a crescent shape,

concave toward the enemy, with a view to force his left toward

Malolos. The two battalions of the 22nd were placed in support

of the left brigade (Otis') of the battle line, the 1st battalion

overlapping the extreme left, the 3rd battalion some distance to

the right.

In front of this part of the line, the ground sloped upward

toward the insurgent positions.

The attacking force moved out in successive

lines of skirmishers, presenting an appearance of great strength.

From their superior positions,

the insurgents at once opened a spirited fire. The approach was

marked with a series of natural obstacles—swamps, lagoons,

marshes,

bamboo thickets, and dense banana groves. Through these, the

American lines advanced unwaveringly and in magnificent order;

the general plan of battle and its execution were typical

examples of strategy and military skill.

The expected insurgent resistance melted away. The battalions of

the 22nd, in close support when all parts of the firing line were

united,

came under sharp fire for five minutes; after that all general

resistance ended. The insurgents retreated in disorder; the

American troops

entered the capital at 10:30 a. m.

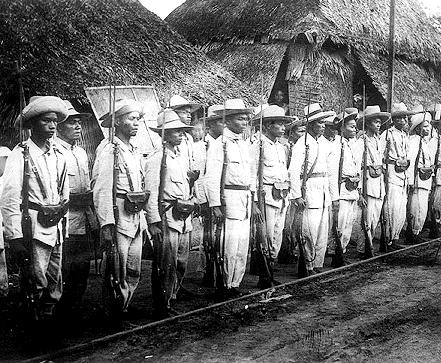

Filipino Insurgents of Aguinaldo's

Army.

Their uniforms and equipment are captured from the Spanish,

and they are armed with Remington designed rolling block rifles

in caliber .43 Spanish.

By his own acts, the enemy's line of retreat

from Caloocan to Malolos had been made a pathway of fire and

needless destruction.

Non-combatants had been forced from their homes, their property

entirely destroyed, by the army whose leaders prated of liberty

and the fatherland. At Malolos, this army was forced to retreat

before it could accomplish its customary vandalism. Before the

American troops

entered the town, columns of smoke were arising from the

principal building, the governor's palace; after the troops were

in possession,

two powder explosions, planned and timed by the Filipinos, shook

the city. With the exception of these damages and the customary

looting

from their own countrymen, the city and its non-combatants were

not injured.

The successful ending of this campaign found

the American forces flushed with success. Their enthusiasm on

entering the insurgent capital

was at its highest. Hardships of the campaign were forgotten in

the general rejoicing and belief that, with the fall of the

capital, fell the insurrection.

On the evening of April 1, the regiment returned by rail to

Manila. April 9, it marched to Pasay and occupied a line of

trenches extending from Pasay,

on Manila bay, toward San Pedro Macati—the southern line

held by the American army at this time. The insurgents held

positions to the front

at distances varying from five hundred to one thousand yards.

Very few of their forces here had been under American fire; as a

result,

almost hourly attacks were made upon some part of the regiment's

line. At night their trenches blazed with rifle fire; under

orders,

the regiment gave back no answering shot. It was the sort of

warfare that robs men of sleep, strains their nerves, and makes

them fret

because of forced inactivity. It was warfare that required all

watchfulness and vigilance, but promised no rewards of victory.

April 19, the regiment returned to Manila and equipped for the

expedition then being organized against the new insurgent capital

at San Isidro.

**********************

Home | Photos | Battles & History | Current |

Rosters & Reports | Medal of Honor | Killed

in Action |

Personnel Locator | Commanders | Station

List | Campaigns |

Honors | Insignia & Memorabilia | 4-42

Artillery | Taps |

What's New | Editorial | Links |