![]() 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry

1st Battalion 22nd Infantry ![]()

The San Isidro Campaign 1899

The Second Northern Expedition - Ballance's Battalion

![]()

Campaign streamer awarded to the 22nd

Infantry

for its service in the San Isidro Campaign

22nd Infantry Soldiers just outside of

Malolos.

Note bugler, center of photo, back row

from a stereoview by Underwood & Underwood,

dated 1899, titled

"22nd U.S. Infantry in Bivouac at Malolos, Philippine

Islands"

Ed., Operations by the US Army compelled Emilio

Aguinaldo to relocate his headquarters from Malolos to San Isidro

in the spring of 1899.

In the late spring and early summer of that year, the First

Northern Expedition had forced him to relocate once again, and

again he moved north,

deeper into the rugged territory of the northern part of the

island of Luzon. In order to prevent him from either escaping by

sea, through the Lingayen Gulf,

or else reaching the safety of the Bulacan mountains, where he

could evade capture for a long period of time, the US command

undertook an attack designed to trap him and his army between two

main forces.

Having long ago abandoned the idea of fighting

set piece battles with the American forces, and reverted to a

guerilla style of warfare,

Aguinaldo's army was now broken up into a number of

organizations, each headed by its own General, and was scattered

throughout

northern Luzon. Carrying out hit-and-run tactics, ambushes, and

delaying actions, the insurgents hoped to wear down the US Army,

and break its will to continue the war. As the Americans would

capture towns and villages, and then move out to pursue Aguinaldo

again,

the insurgents would move back in, and the US Soldiers would find

themselves having to fight to regain control of those same towns.

Thus, the aim of the Second Northern Expedition

was to cut off Aguinaldo's ability to receive arms and supplies

by sea,

occupy the north-south railroad running from Manila to Dagupan,

therby preventing Aguinaldo from rapid movement of his forces,

and cutting off his avenue of escape to the mountains in the

east. By this broad containment of the insurgent army, it was

hoped

the insurgency could be starved of supplies, arms and ammunition,

to the point where its surrender would be inevitable.

SECOND NORTHERN EXPEDITION BALLANCE'S BATTALION

Holding the permanent rank

of Captain, and the brevet rank of Major, The photo at right was taken

some years earlier, Photo from the National Archives |

John Greene Ballance |

It was known that the enemy in the north,

receiving accessions from the southeastern provinces, intended to

retire to the mountains

to the north and east if worsted in the lowlands and on the

plains; from the mountains the enemy believed himself able to

prolong the war indefinitely.

Secret information numbered insurgent rifles in the north at

25,000. The main part of this army was operating along the line

of the railway

from Angeles to Dagupan, throughout the provinces of Tarlac and

Pangasinan, and in parts of Nueva Ecija and Bulacan.

The plan of campaign was to hold these forces

in their position until the American army closed the northern and

eastern roads of egress

to the mountains; then to capture or to scatter the insurgents,

to take possession of the railroad, and to pursue retreating

columns or detachments.

Three forces were used to execute the plan. At Angeles, General

MacArthur's command had for its objective the insurgents along

the line

of the railway; another force, under General Wheaton, proceeded

by sea to San Fabian, with orders to move east and south, closing

the roads

to the mountains and eventually making contact with the third

force—General Lawton's—that moved from San Fernando,

through Arayat

and San Isidro, thence north through Cabanatuan, Talavera,

Humingan, and Tayug, to San Nicolas.

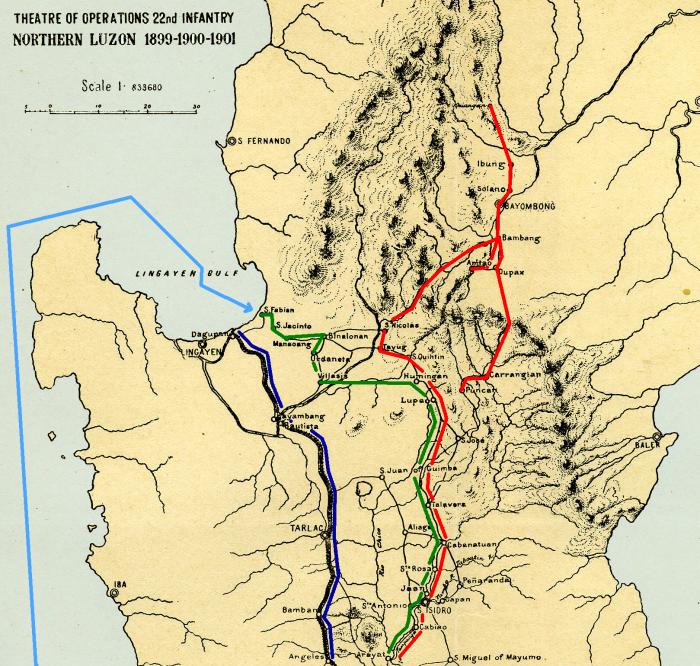

Map of the Northern Luzon campaign.

The three pronged attack by the US Army

was designed to push Aguinaldo's army steadily northward,

until it became trapped by two opposing American forces. The

attack consisted of MacArthur's command ( dark blue line ),

moving along the Manila-Dagupan railroad from Angeles to Dagupan,

and Wheaton's command ( light blue line ),

steaming from Manila around the northwestern edge of Luzon,

coming through Lingayen Gulf and landing at San Fabian,

while Lawton's command, with Young and the two battalions of the

22nd Infantry ( red and green lines )

moving to cut off any possibility of Aguinaldo's army heading

east to take refuge in the mountains.

Map from the 1904 Regimental History

Colorized and routes added by the website editor

|

Samuel Baldwin Marks Young,

Brigadier General of Volunteers, |

To General Young was assigned the immediate

command of the third column. Fighting daily, making forced

marches through seas of mud,

on half rations, shoeless, and lacking clothes, the troops of

this command performed the task assigned them; they skirted the

base

of the mountain ranges and effectually closed every avenue of

escape from the lowlands. One battalion of the

regiment—Ballance's—

played the leading part in this last campaign of the war; a

second battalion—Baldwin's—made a march unequalled in

Philippine warfare.

The troops assigned to General Young were:

Two battalions 22nd infantry;

24th infantry;

two battalions 37th infantry;

one squadron 4th cavalry;

two squadrons 3rd cavalry;

two companies Macabebe scouts;

34th infantry;

and two companies American scouts.

During this campaign, the remaining battalion

of the regiment garrisoned the towns of San Luis and Candaba,

keeping the river open and forwarding supplies to the army in

front.

|

The route of Map from the Colorized and |

General Young's advance from Arayat was begun

on the evening of October 17. Ballance's battalion crossed the

river at dark

and proceeded up the river to Balasin, with orders to clear the

way for the main column, which was to move on the following day.

The insurgents were reported strongly intrenched at Maglibutad.

Lowe's scouts were ordered to move up the right bank of the

river;

the Macabebe scouts were ordered to move up the left bank, and by

a night march, to get in rear of the enemy.

Shortly after dawn, October 18, the scouts of Ballance's

battalion located the enemy intrenched near Maglibutad.

The Macabebes had failed to gain their assigned position. The

first battalion made a direct assault on the works, and after a

fierce resistance,

carried these works, and inflicted on the enemy a loss of 104

killed, wounded, and captured. The main body of the insurgents

retreated

toward Cabiao, the battalion's objective.

Considerable opposition was expected at Cabiao;

but demoralized by their defeat at Maglibutad, the insurgents

made only a slight attempt

to hold the town. The battalion occupied this place at 10 a. m.

During the afternoon, a strong force of battalion scouts

made a reconnaissance toward San Isidro. One mile north of

Cabiao, they were fired upon by the enemy. After slight

resistance,

the enemy fell back to San Fernando, where from both sides of the

river they opened a sharp fire. Due to confusion, the insurgents

on the right bank of the river began to fire upon their own men

on the other side of the river. The demoralization produced by

this fire

and the efficiency of the scouts' fire, caused them to retreat,

although intrenched and in greatly superior numbers.

October 19, the main command moved from Cabiao,

the first battalion acting as advance guard. A small body of

scouts,

selected from the battalion, preceded the advance guard as an

infantry screen. Beyond the barrio of San Fernando,

the scouts were fired upon by a body of insurgents that were

destroying a bridge across an unfordable stream.

The scouts rushed the bridge, crossed on the stringers that had

not been destroyed, and despite a loss of 25 per cent of their

number,

held the bridge against a superior force until the advance guard

arrived. The remainder of the battalion came up on the run,

deployed in mud and water on both sides of the road, and drove

the enemy back toward Calaba. In this barrio, the insurgents

had strengthened the natural barricade formed by a bamboo

thicket. In front of the thicket was an open space,

averaging forty yards in width. The insurgent skirmishers,

keeping well concealed, had fallen back until they massed behind

the barricade.

Reaching the open space, the battalion, in skirmish line,

suddenly received a heavy fire at close range. Without

hesitation,

the battalion charged the barricade and drove the enemy out. Had

the distance been greater, or the marksmanship of the Filipinos

better,

this position could not have been taken without great loss. The

ambuscade was well planned; but the prompt charge completely

demoralized

the insurgents and forced them, in hurried retreat, toward San

Isidro. Continuing the advance, one company was sent

along the river road, the remainder of the battalion on the

direct road to San Isidro. At this place, considerable opposition

was expected,

and the battalion was reinforced by three troops of dismounted

cavalry and six guns. The insurgents were found some distance

from the town;

Ballance formed lines on each side of the main road, advanced

across the submerged rice fields, drove the enemy through San

Isidro,

and pursued them as far as the barrio of San Nicolas.

Killed in action, October 19, 1899:

Corporal Ephraim S. Yoder, company K.

Wounded in action, October 19, 1899:

Private Griffin Andrews, company F;

Private Charles H. Pierce, company I;

Private Handy B. Johnson, company K;

Private Claud B. Day, hospital corps.

|

Medal of Honor ( of the type awarded in 1899 ) Ed., The group of scouts who held the

bridge just beyond the barrio of San Fernando, The 1904 Regimental History made special mention of Private Pierce's actions: "Private Charles H. Pierce,

company I, continuing to fire after he had been severely

wounded, |

|

Rank and organization:

Private, Company 1, 22d U.S. Infantry. Citation: Held a bridge Photo courtesy of Tracy Morrow |

"Charles

Henry Pierce" was born February 22,

1875 in Cecil County, Maryland, the son of Charles W. Pierce.

Pierce

left his father's farm near Chesapeake City, Maryland and joined

Company M, 1st Delaware Infantry on May 17, 1898

at the age of twenty-three to help his country in the war with

Spain which had broken out on April 25th of that year.

At the time of his enlistment he was described as 5' 6"

tall, blue eyes, brown hair and a fair complexion.

The war

was basically no contest and ended in a matter of months. Pierce was

discharged on December 19, 1898,

and less than a week later he enlisted in the regular US Army. He

was assigned to the 22nd US Infantry and sent to Fort Crook,

Nebraska.

As a

consequence of the short-lived war, the United States not only

got control of Cuba, but the Philippine Islands as well.

An insurrection was being led in the Islands by Emilio Aguinaldo.

Thus ensued a three year guerilla war

involving 70,000 American soldiers at a cost of 175 million

dollars.

On

October 19th Major John Ballance, 22nd Infantry, was placed in

command of an advance guard of troops.

Out in the front 500 yards was a group of scouts led by Sergeant

Charles W. Ray. One of the twelve scouts was Private Charles Pierce.

As they

approached the Rio Grande River the scouts saw a bridge which had

had its planks removed to slow down

the advancing Americans. On the other side of the bridge were

about 200 enemy soldiers. Sergeant Ray led his scouts in a mad

dash

for the bridge as they attempted to cross on its stringers. The

insurgents let loose with a volley of fire.

Private Pierce

was hit by a Remington bullet in the left thigh but refused to be

taken to the rear.

He insisted on staying with his buddies in defending the bridge.

The

scouts were compelled to hold the bridge for quite some time

before the main body arrived. By the end of the year

Philippine resistance had finally been broken. On March 10, 1902,

Pierce

and Sergeant Ray were awarded the Medal of Honor.

Pierce appears to

have made a career out of the Army and ended his career as a

Lieutenant. He retired in the late 1920's

or early 1930's. He died March 2, 1944 and was interred in

Valhalla Memorial Cemetery in North Hollywood, California.

Biography of Charles Pierce by Russ Pickett

|

Rank and organization: Photo courtesy of : |

As they fought their way toward San

Isidro, Ray led 12 advance scouts ahead of the main U.S. force.

His orders were to report any enemy activity and await further

orders.

Before long, Ray encountered Filipino insurgents a few miles from

the town of San Isidro as they began sabotaging a bridge

on the Rio de la Pampanga, one the Americans needed to cross to

continue with their operations. Ray realized

that if the bridge was to be saved he could not wait for orders,

so he sent one scout to request reinforcements,

then proceeded to the bridge. On arrival, Ray’s unit crossed

the stringers, or horizontal support beams,

because the insurgents had removed the bridge planks to slow

their advance. Complicating Ray’s tenuous situation,

about 200 Filipinos were positioned on the other side.

According to one source, “Ray led his scouts in a mad dash

for the bridge. …The insurgents let loose with a volley of

fire.”

Three Americans were wounded, and Ray ordered them to stay back

for treatment, but Charles Pierce refused to take cover

and continued to fire his rifle. Ray and his fellow scouts held

the bridge until U.S. reinforcements arrived an hour later

to drive away the insurgents. The bridge was saved from

demolition, and Pierce and Ray earned the Medal of Honor.

Ray received his medal by mail in Democrat, North Carolina, where

he was living in 1902

Ray was born to Newton and Rachel Elizabeth (McPeters) Ray on

August 6, 1872, in Yancey County, North Carolina.

The family worked as farmers and the children were raised on

“wild meat,” according to Ray’s brother.

Charles received an elementary school education and tried a

number of jobs as a young man, including toiling as a steel

handler

at a quarry in West Virginia, a roustabout in a circus, and a

hired farmer in Iowa, probably in Delta for an unknown time

period.

Ray began his military service with the 22nd Infantry in St.

Louis during the autumn of 1898. In Manila by December,

when the insurrection broke out, he participated in 22

skirmishes.

After his Medal of Honor action, Ray and 1,000 other soldiers

contracted malaria. Placed on the hospital ship Relief

to recuperate in Hong Kong, he then returned to duty and was

assigned to accompany a wagon train back to his unit.

Impatient with the slow pace of the wagons, he received

permission to hike ahead on May 15, 1900. This proved a costly

mistake

when he was ambushed, beaten and stabbed severely by insurgents,

who hearing the advance of U.S. troops,

dragged the nearly dead soldier to hide him in a hut. He had

suffered 22 wounds on his back, neck, arms and hands.

Luckily, Ray heard a mail hack rolling by and cried out for help.

Doctors reported that had he been discovered a few minutes later,

he would not have survived. A tourniquet was applied to his arm,

but not soon enough to prevent amputation.

Following his second recuperation, Ray briefly returned to bid

farewell to his unit. Prior to his discharge that December,

one-armed Ray participated in one last skirmish. For his efforts,

the Scouts gave him a mahogany cane with a Spanish silver-dollar

top,

a collar including his name, and a silver ferule at the bottom.

A pension claim Ray filed in 1900 documents his post Medal of

Honor service, during which he suffered a number

of excruciating wounds before retiring in December 1900. The

claim lists his physical characteristics as standing five-feet

nine,

with brown hair and blue eyes. He reported his injuries at Barrio

San Fernando in Luzon that March. In addition to the bolo

(a sword-like weapon) wounds resulting in the loss of his left

arm, the malaria impaired his digestion, and ulcers caused him

to suffer (at least temporary) blindness.

Ray returned to North Carolina after his military service. In

1905, he bought land during the Oklahoma Territory land rush.

While living out his life as an Oklahoma homesteader, he once

went back to North Carolina to find a wife.

Settling into farm and church activities, Ray and his wife,

Myrtle, had seven sons and one daughter.

In 1951, he became a founder and was elected president of the

Oklahoma Chapter of the Legion of Honor.

He died at the age of 87, on March 23, 1959, in Grandfield,

Oklahoma.

Narrative on SGT Charles Ray from:

the State Historical Society of Iowa

General Young's command remained at San Isidro

until October 27, when at five o'clock in the morning the advance

was resumed

by the first battalion of the regiment, reinforced by Lowe's

scouts, six guns, and one dismounted troop of cavalry.

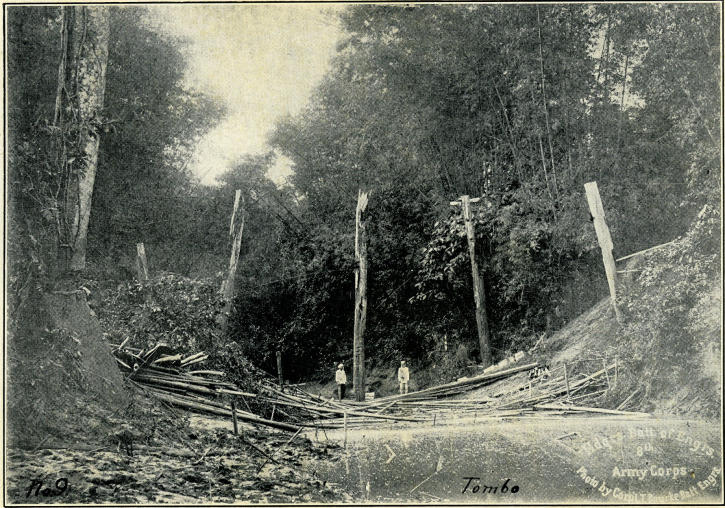

At the Tombo river, the insurgents had destroyed the bridge and

built intrenchments commanding the crossing. Leaving the

artillery

to come up with the main column, the infantry crossed on bamboo

floats, drove the enemy from the trenches, and pushed rapidly

forward.

A mile beyond, a company of the famous Manila battalion was seen

hurrying toward the Rio Grande to attack a gunboat;

company F promptly engaged them, scattering them to such an

extent that, in their gaudy red trousers, straw hats, and fancy

blouses,

they were never again seen as an organization.

Several miles beyond, the advance guard

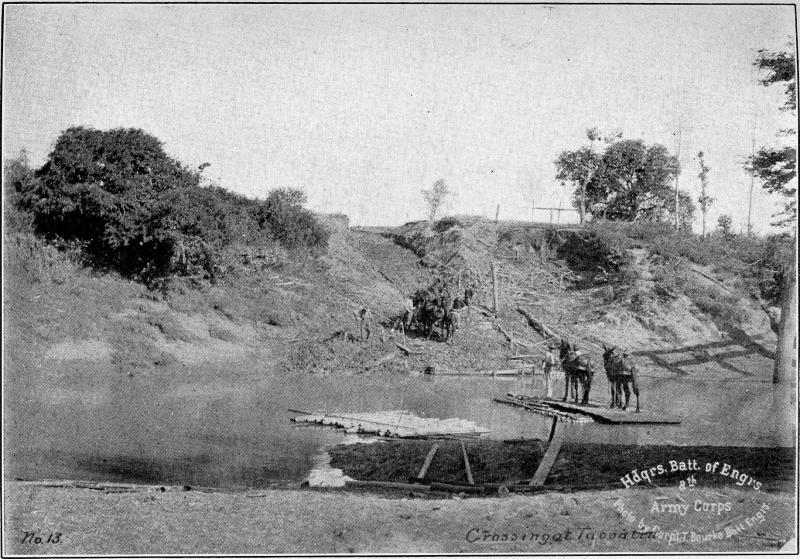

encountered one of the enemy's outposts near the Taboatin river.

Reconnaissance showed

that the bridge at this point had been completely destroyed, that

the river was unfordable near the crossing on account of recent

rains,

that the banks were very steep, and that the insurgents occupied

a line of trenches, 800 yards long, on the opposite bank. Lowe's

scouts

and company A were sent to make a long detour to the right, and

to cross the river two miles above the trenches in order to get

in the insurgents' rear.

The battalion scouts and company K crawled through the high

grasses until they were separated from the trenches by only the

width of the river.

Meanwhile the artillery, brought forward again, was posted,

loaded, and aimed at the trenches. These preparations were made

so secretly

that the insurgents were in complete ignorance concerning them.

Filipino sentinels, on the opposite bank, watched the river and

main road,

wholly unconscious of the attack. At a signal, fire was opened by

the infantry and the artillery. It did good execution and kept

down

the fire of the enemy, but failed to drive them from their

trenches. Unforeseen difficulties had prevented the scouts and

company A gaining

their flanking positions; two other companies were sent up the

river, with orders to cross about half a mile above the trenches

and take them

in the flank. Wading, swimming, and floating on bamboo, the

companies succeeded in crossing the river; the insurgents

discovered the movement,

and after firing a few volleys at the troops in the water,

abandoned their trenches and retreated through the tall grasses

beyond

Santa Rosa. The remainder of the advance guard built a raft and

crossed the river; in the evening the command entered and

occupied Santa Rosa.

Killed in action, October 27, 1899:

Private Herman H Stone, company K.

Wounded in action, October 27, 1899:

Corporal Charles F. Sparger, company K.

Private George J. Marks, company F.

The crossing over the Taboatin River.

Two pack mules are being brought across on a raft.

Part of the bridge destroyed by the insurgents can be seen in the

extreme right.

Photo from the 1904 Regimental History

October 30, the battalion advanced and captured

Cabanatuan, containing an insurgent arsenal.

October 31, General Young's headquarters moved into Cabanatuan.

November 7, the battalion was ordered to Talavera. The river at

Cabanatuan was a raging torrent; while the engineer corps were

building

a permanent ferry, the battalion constructed a temporary ferry

that was eventually used to cross the entire division. The

construction

of this ferry was attended with great dangers; during the work

one man was drowned; four men were rescued from the torrent by

heroic efforts

of their comrades. The ability of men and officers of this

battalion to march, to fight, to do the work of other corps, and

to risk life for each other,

won for it the admiration of all troops of Young's army.

From Arayat to Cabanatuan, Ballance's battalion

had been constantly in advance. Beyond Cabanatuan it became

necessary to cover the roads

with slough grass and brush in order to drag the carts over them.

For two miles, the bulls could pull only the empty carts;

soldiers carried the supplies

until a better road was reached; finally one company was left

with the train; the other companies pushed forward and occupied

Talavera, November 9.

At Talavera an order was received for part of the battalion to

act as escort to the division train. Subsequently this order was

changed,

and on November 10, the battalion occupied Munoz; on the 11th,

San Jose; 12th, Lupao; 13th, Humingan. By this time, the shoes

and clothing

of the men were in a deplorable condition; the number of men

marching barefooted became greater daily. At San Jose orders had

been received

to leave all impediments behind; the battalion had left this

town, carrying nothing but rifles, 100 rounds of ammunition per

man, one day's field ration,

and three emergency rations. Two miles out from San Jose, the

battalion had passed a troop of cavalry, which left San Jose

twenty-four hours

before the battalion, hopelessly stuck in the mud.

November 14, leaving one company to hold

Humingan, the remaining three companies cut loose from the main

command, with orders

to proceed to Resales, thence to attack the insurgent army at

Urdaneta, reported 2000 strong. So great was General Young's

confidence

in the ability of this battalion, that he ordered three

companies, accompanied by only two pieces of artillery, to get in

rear of the main insurgent army,

variously reported to be from 5000 to 24,000 strong. Moving with

great caution, unimpeded by wagon train, the battalion outflanked

a strong intrenchment of the insurgents at Bulango, the

demoralized enemy retreating without firing a shot. At the

Matablan river, swollen by rains,

the insurgents had destroyed the bridge, taking up the flooring,

cutting the stringers, and dropping them into the river. On the

opposite bank,

they occupied strong intrenchments, from which they opened fire.

Friendly natives stated that the river in its present condition

could not be crossed.

A detachment, sent above the bridge to fire on the insurgents if

they retreated, swam the river, contrary to native belief, and

opened a fire

on the enemy's right; a company, sent to get in rear by way of

the Agno fords, opened fire on his left. These flanking fires,

combined with fire

from the remaining troops in the direct front, forced the

insurgents to abandon their trenches, after which, in two hours

time and with only

one ax and one hatchet, the bridge was repaired sufficiently to

cross the two pieces of artillery. The bridge over the river in

front of Resales

had been completely destroyed; by making a wide detour through

the swamp, the command entered Rosales at dark; the insurgents

retreated

as the battalion entered the town; but as the command had eaten

nothing since daylight, further pursuit was not made.

A great quantity of insurgent stores and records was captured in

the town.

On the following morning, in a furious

rainstorm, the command proceeded to Carmen, where a raft was

built to ferry men and artillery

across the Agno, too high to ford and too swift to swim. By

eleven o'clock at night all except company F had crossed; the

river had become a torrent,

so full of floating debris that it was impossible to cross. The

part of the command that had crossed the river proceeded to

Villasis, arriving there

at midnight and sleeping in the mud, supperless. During the night

an order was received directing the command to march to

Binalonan,

the insurgents having abandoned Urdaneta. Entering Urdaneta, the

command was welcomed by a brass band and escorted to the plaza

by the principal men of the town. The departure of the insurgents

and the subsequent arrival of the Americans were marked with

great rejoicing

on the part of the non-combatant natives. Fruit, tobacco, and

meat were freely distributed among the soldiers; a din of ringing

church-bells

proclaimed the news far and wide.

After this novel reception, the command

proceeded to Binalonan. Three miles of the way was through two

and a half feet of running water,

causing great suffering to the scantily-clothed men already

suffering with colds, fever, and bleeding feet. The insurgents

evacuated Binalonan

before the arrival of the American troops, and the command was

directed to occupy the town until ordered elsewhere.

November 20, the battalion was sent back to Villasis, to scout

all roads leading from there in order to learn the whereabouts

of General MacArthur's advance. Through a messenger it was

ascertained that General MacArthur had arrived at Bautista,

November 19,

five days after the battalion had occupied Resales.

November 23, 24, 25, the battalion marched to

San Fabian. Here rations, clothing, and shoes were expected;

rations alone were received.

The battalion was willing and anxious to push on in pursuit of

the remnants of Aguinaldo's army, but orders directed it to

remain at San Fabian.

Then came the relax. Through sheer effort and American grit, the

men had kept to their work. They were sick with fever and

dysentery;

they suffered with dobie itch and bruised and bleeding feet; they

had lived on half rations and on no rations; they had walked

through mud and water;

swimming, wading, rafting, bridging, they had crossed fifty

streams and rivers; invariably wet, they had been exposed to the

cold nights

without blankets or covering of any kind; they had covered the

advance of General Young's army from Arayat to San Jose, fighting

almost daily,

at times making several fights a day; beyond Talavera, they had

pushed alone into the insurgent strongholds, with orders to get

in rear

of an insurgent army that three separate American armies had been

sent to conquer; they had never failed to accomplish a task

assigned them.

Gallantly led by an officer of indomitable will, and who by the

ill-fortune of promotion no longer serves with the battalion he

loved,

these men won the admiration of commanding generals; throughout

campaigning privations unsurpassed in American history,

they showed the grit and heroism of their race.

Upon receipt of the order for the battalion to

remain at San Fabian, the necessity of further mental effort

ceased. Tired nature,

held so long in check, assumed control. In one day, three hundred

men collapsed with fever and dysentery contracted during the

arduous campaign.

December 3 to 7, the battalion returned to its former station,

Candaba.

Three facts attest the efficiency of Ballance's

battalion: with engineer troops accompanying the expedition and

working upon a ferry

at Cabanatuan, the battalion, under rush orders, constructed a

second ferry that was used to cross the entire army; with twelve

troops of cavalry

accompanying the expedition, the battalion formed the advance

guard from Arayat to San Jose, the battalion scouts forming an

infantry screen;

with many excellent organizations accompanying the command, with

many more in the United States army, General S. B. M. Young

made the following statement in his official report of this

campaign:

"Without reflecting in the least on

the many other excellent battalions in the army, I consider this

battalion

as the finest and most efficient one I have ever seen in the

American army."

The destroyed bridge over the Tombo river.

Photo from the 1904 Regimental history

Home | Photos | Battles & History | Current |

Rosters & Reports | Medal of Honor | Killed

in Action |

Personnel Locator | Commanders | Station

List | Campaigns |

Honors | Insignia & Memorabilia | 4-42

Artillery | Taps |

What's New | Editorial | Links |