![]() 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry

1st Battalion 22nd Infantry ![]()

The San Isidro Campaign 1899

The Second Northern Expedition - Baldwin's Battalion

![]()

Campaign streamer awarded to the 22nd

Infantry

for its service in the San Isidro Campaign

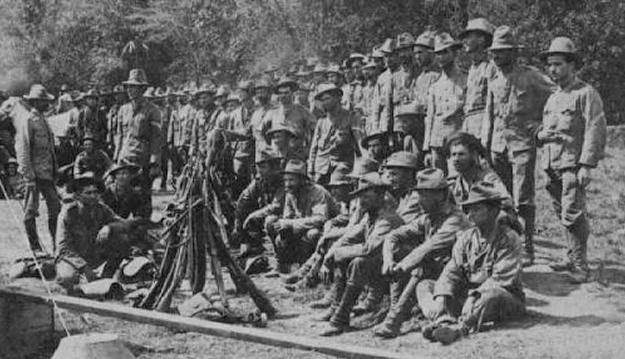

Company I, 22nd Infantry

from a stereoview by Underwood & Underwood,

dated 1899, titled

"Co. I, 22nd U.S. Infantry, encamped at Malolos, Philippine

Islands"

SECOND NORTHERN EXPEDITION BALDWIN'S BATTALION

In the meantime, General MacArthur's command

moved from Angeles, November 11, and entered Dagupan, November

20.

General Wheaton's command arrived at San Fabian, November 7, and

by November 19 had occupied the line from San Fabian,

through San Jacinto and Manaoag toward Binalonan. The plan of

campaign had been fully executed.

The insurgent armies had been beaten wherever encountered. The

remnants were scattered through four provinces, unable to

reorganize.

But their leader had escaped. In disguise, he had penetrated the

lines. November 17, General Young sent the following message to

Manila:

"Aguinaldo is now a fugitive and an outlaw, seeking security in escape to the mountains or by sea."

November 19, General Lawton wired as follows:

"It is my opinion that Aguinaldo

should be followed every moment from this time. He should not be

permitted to establish himself

at any point or again organize a government or an army. Wherever

he can go, an American soldier can follow;

and there are many who are anxious to undertake the

service."

The honor of proving General Lawton's high

estimate of the American soldier was given to a battalion of the

regiment.

Mountain trails stained with blood from lacerated feet, and eight

soldier dead buried along the trails, attest the hardships.

October 18, the 3rd battalion (Baldwin's) was left at Arayat,

charged with guarding the town, scouting, and forwarding supplies

to General Young's army. Cascoes carrying supplies required

guards; wagon trains moving to the front demanded protection.

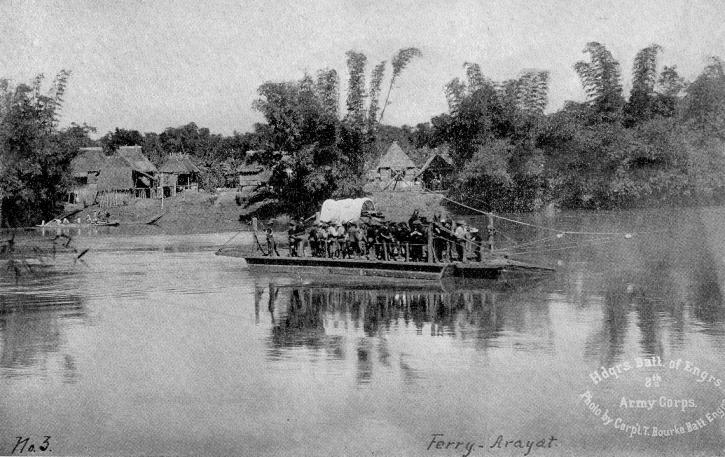

By General Young's order, the north bank of the Rio Grande de

Pampanga was scouted daily; the important ferry at Arayat

was manned and guarded. The great quantity of stores passing

through the town necessitated strong outposts; to insure the

forwarding

of these stores across the ferry was in itself work for a

battalion. Due to intermittent heavy rains, the river rose and

fell rapidly,

the corduroyed approaches to the ferry at high water were dug

from the mud and slush as the water fell, only to be replaced

after the next rain. At one time, a passing casco cut the ferry's

main rope; the river at the time was a raging torrent;

only after hours of steady work was it possible to carry across

the river the lightest line; to cross the spliced rope of the

ferry

required the employment of every native banco that could be found

for miles up and down the river.

Officers and men worked constantly in water for thirty-six hours

in order to repair this break,

in order to cause no delay in forwarding supplies to the army in

front.

The ferry at Arayat, loaded with Soldiers and a wagon with mules hitched.

Photo from the 1904 Regimental History

The work of the battalion during its occupation

of Arayat, October 18 to November 9, taxed the physical resources

of the men to the utmost.

November 10, the battalion was relieved and ordered to the front.

The roads were a mass of mud; in two days, marching from daylight

until after dark, the battalion moved only twelve miles; over

much of this distance the carts were pulled by hand by soldiers.

Passing through Libutad, Cabiao, San Isidro, and Santa Rosa, the

battalion arrived at Cabanatuan, November 15.

Killed at Bayombong, November 15, 1899, while a prisoner in the hands of insurgents—Private John Neil, company L.

Under orders of the brigade commander, the

battalion remained here until November 22, repairing nearby

bridges.

Late in the afternoon of the 22nd, the brigade commander gave the

battalion the following note:

"General Lawton says he sorely needs you and your battalion.

Rush on to Tayug. The only orders I get are, hurry."

Responding to this order, the battalion left all transportation

under guard and pushed to the front.

The roads beyond Cabanatuan beggared description. Rains had made

them a sea of mud; where the sun had made a slight improvement

was a glutinous mass, mixed with dead grass and vegetation.

Abandoned carts, dead carabaos, were

everywhere. The division ambulance, with its red cross of mercy,

lay along the road,

an abandoned wreck. Miles of mud-stuck wagon trains dotted the

sea of mud; living carabaos floundered; mud-begrimed soldier

guards,

with tireless energy, worked and swore; chino bull drivers filled

the air with exhortations to their carabaos. Never was scene more

illustrative

of the self-reliance of American soldiery. Each mud-streaked,

swearing soldier showed that nothing human could prevent the

supplies on his cart

from reaching their destination—the army in front.

Unimpeded by wagons, the battalion slowly

forged its way past the supply trains. Good-natured salutations

were exchanged between the command

and the wagon guards. Almost insurmountable obstacles were met

and overcome; physical strength was taxed most heavily;

indomitable wills laughed and joked at hardships. Making two

forced marches a day, on half ration, the battalion arrived at

Tayug

and reported to General Lawton, November 25, marching on this day

twenty-six miles. November 26, the battalion marched to San

Nicolas

and received instructions to proceed on the following day to

Bayombong, province of Nueva Viscaya. At this time, the insurgent

forces

had been scattered. It was believed that Aguinaldo had crossed

the mountains; the battalion's work was to prevent a reorganizing

of these scattered forces in the Cagayan valley and to intercept

small bodies of insurgents that might attempt to move southward

into southern Luzon..

Map from the 1904 Regimental History |

Left: The route of Further marches

Major John A. Baldwin, Baldwin was promoted to Major

of the |

The trail to Bayombong was called by the

natives, the "Infernal trail." This trail led over a

succession of mountain ranges so steep

that ascent and descent was made by zig-zag levels; at times, in

climbing over them, one could hear the voices of comrades in the

distance,

some apparently directly under his feet, others directly above

his head. Looking upward and backward after a steep descent,

one could see at times soldiers on twenty different levels,

winding, zig-zagging down the declivity. So laborious was the

work

that frequently halts were made every ten minutes to allow men to

regain their wind.

The lower parts of these mountains were covered

with tropical growths; the heights were pine-clad. In many

places, tall grasses lined the trail;

in places it led over a narrow shelf cut in the faces of the

perpendicular mountain sides—a false step meant a plunge

five hundred feet downward.

The trail led over numerous mountain streams; during one day's

march, the same stream was forded twenty times. Other streams

were so swift that only the largest and strongest men could make

the first crossing with safety, men of ordinary size were aided

by ropes

and vines stretched across by their stronger comrades.

The nights passed on this trail were very cold.

Men were clad only in light garments; they carried no blankets.

Shoes, stockings,

and trousers were wet during the entire journey over the trail.

Men slept from exhaustion until the cold aroused them; huddled

around camp fires,

they slept and kept warm as best they could. From San Nicolas to

Bayombong is a six days' trip for natives accustomed to mountain

traveling.

At San Nicolas the battalion was given three days' reduced

rations; thereafter the battalion was to live off the country.

Two native guides accompanied the command; on the first night

out, they deserted.

At the first camp in the mountains, a

detachment of forty men of the 24th infantry was found. The men

had been lost for two days,

and were practically out of rations. After the guides' desertion,

the command took a wrong trail, but fortunately captured an

Igorrote

and impressed him as a guide. Strange to say, this Igorrote was

the only native seen during the passage across the mountains.

When captured, he was greatly frightened; kind treatment

succeeded in only partially allaying his fright. He led the

command back

over a deer trail to the Bayombong trail, without loss of much

distance, but with great loss of physical energy.

About midway across the trail, at Cayapa, there

were remains of an old Spanish cuartel. Here was found a quantity

of old, musty, rain-injured rice.

It was dried in the sun and issued as food; without it, the

sufferings of the battalion would have been greatly increased.

Beyond Cayapa, the effects of the march began to tell on the

command. Many men were barefooted; their feet were lacerated by

sharp stones.

Chills and fever had fastened their grip on many men; dysentery

was common to all. Medicine was limited. Men watched for

opportunities to crawl,

unnoticed, from the trail to the tall grasses. Routed out by the

rear guard, many men begged to be allowed to remain and to die.

Only by threats,

only by actual violence, was it possible to get all men into camp

at night. Several became so sick that it was necessary to carry

them;

along parts of the trail this seemed impossible, yet it was done.

One man broke down under sickness and became mentally deranged;

at night, his wild cries echoed over the mountains, necessarily

having a depressing effect upon the other sick men. But, as is

always found

among American soldiers, there were many men, no less sick, no

less depressed, but always ready to meet misfortune with a

laugh—

these men saved the command. Always good-humored, always ready to

help a weakened comrade, they retained their health by sheer

force of will;

they imbued others with the belief that nothing was impossible.

At ten o'clock on the morning of December 2nd,

the battalion entered the pueblo of Bayombong. In this province

the Tagalo

had never been supreme; his newspapers had not circulated the

great dread of the American soldier. Cunningly-worded Tagalog

proclamations,

supporting any form of power that could protect the natives from

American rapacity, cruelty, and lust, had not been scattered

broadcast.

Consequently the exhausted command was royally received by the

people of the town. The governor of the province had provided an

excellent dinner

for the entire command; from his house hung an American flag made

especially for the occasion by the women of the town;

everywhere the people showed genuine pleasure and satisfaction at

the advent of the American forces. It was a strange experience

for the battalion;

towns in provinces on the other side of the mountains had

received them either with musketry or in sullen silence. Never

before

had the battalion been greeted with Filipino cheers; never before

had they found a dinner waiting for them. The men were ragged,

hatless, footsore; they suffered with fever and with dysentery;

hunger had gnawed at them for six days, and lo! at their

journey's end,

a dinner awaited them—a dinner at which each man was allowed

to eat his fill.

The people of Nueva Viscaya had been insurgents

only in name. Agents of Aguinaldo had been among them, had left

them a few rifles,

had issued commissions to a few officers. In the pueblo was a

partially constructed building that the insurgent chieftain had

intended to occupy

when driven to flight by General Young's army; natives did not

dream that American forces could cross the mountain trails.

When the organized forces of the insurrection had been completely

shattered, it was believed that Aguinaldo, with a few hundred

followers,

had escaped to the mountains of northwestern Luzon; subsequent

events proved this a fact. A battalion of the 24th infantry

had entered Bayombong, three days before the battalion of the

22nd; this first battalion, leaving their sick at Bayombong, had

continued the march

down the Cagayan river. The two battalions prevented the

insurgents from reorganizing their shattered forces, and

compelled Aguinaldo

to remain a fugitive in the mountains. To accomplish these ends,

the battalion of the 24th made a march famous in Filipino

warfare;

the battalion of the 22nd marched and suffered and buried its

dead, achieving no brilliant results—simply obeying orders.

The command had lacked medicines for some time.

Native remedies were tried without success. While in Bayombong,

rice and native beef

in small quantities had been obtained; while sufficient for men

in good health, they were not proper food for sick men.

December 8, the battalion was ordered to return to San Nicolas.

One officer and twenty men, too sick to travel, were left at

Bayombong.

The condition of the command made it impossible to return by the

' 'Infernal pass;" the Carranglan pass, to the south, was

accordingly selected.

It proved but little better, Caballo Sur, its highest mountain,

taxing the strength of the men to the utmost. Rains had washed

all earth

away from the trail, slippery rocks and boulders caused great

suffering to the shoeless command. Near the summit of the

mountain,

the battalion was compelled to bivouac at an old cuartel. The

night was intensely cold, rain fell in torrents, shelter was

obtained for only a few

of the sickest men; it was impossible to keep fires burning;

vermin of many kinds infested the cuartel. In the spirit that

laughs at hardships,

the men christened the spot, "Camp Misery."

December 11, the command arrived at Puncan. The

marches had been daily struggles for existence. The country had

few inhabitants;

rice was obtained only in handfuls; men cooked all sorts of

tropical plants, but found them lacking in flavor and

nourishment;

carabao meat was a luxury. Puncan was within a day's march of

commissary and hospital; but at Puncan, under orders, the

battalion

turned its back upon the things that meant health, even life, and

retraced its steps to the mountains. Five days' rations, without

bacon,

and a small quantity of medicine, were sent with the command.

December 13, in grim and soldierly silence, the battalion turned

to the rough

and rugged heights of Caballo Sur, where again men could be

tracked along the rocks by the blood from their feet.

Under instructions, companies B and C were left

at Carranglan; the other two companies arrived at Bayombong,

December 16.

Two days later, company H was sent to Quiangan, thirty-five miles

distant, to investigate reported insurgent stores.

The trail entering this Igorrote town was said to be the only

entrance to a high valley beyond; for miles the men were obliged

to march in a crouching attitude, crawling over fallen logs,

climbing over slippery rocks. Couriers could not be induced to

travel along this trail

unless in parties of at least ten men. Uncivilized Igorrotes,

concealed, watched movements of the command; the first sergeant

of the company

was grazed by a thrown spear; a private, wandering from the

trail, was killed; his head and arms were cut from his body.

Wounded in action, December 20, 1899:

1st Sergeant Ernest A. Bonge, company H.

Killed in action, December 20, 1899:

Private John H. Kelly company B.

A considerable force of insurgents was located

at Bocaue, beyond Quiangan, but under positive orders the company

was compelled

to return to Bayombong without attacking them. December 25,

thirty-six men of company L, all that were able to march,

were sent to Aritao, to investigate reported insurgents. A force

had been there, but had gone farther into the mountains.

Several days later, a superannuated Tagalog, the tool of a

reformed insurgent, began working strange influences among the

people of Solano.

In a whining, sepulchral voice, he declared himself to be the

"Holy Ghost." Immediately it became more difficult to

obtain rice;

burden bearers became impossible. Even after this fraud had been

exposed, his influence was still felt.

December 29, the battalion quartermaster, after most arduous

work, brought the battalion shoes and clothing, so sorely needed.

January 7, 1900, the battalion, under orders, again crossed the

mountains. Again Camp Misery was sighted; again the cross-crowned

Caballo Sur was climbed; again men suffered.

January 16, the battalion reported at

regimental headquarters at Arayat. This battalion had been

detached from the 2nd division

and assigned to the division that scattered the insurgent armies

and drove them, terror stricken, from their capital to the

mountain fastness.

Throughout this last great campaign, the battalion gained no

honor of engagement—its record is that of duty and of

endurance.

It marched nearly, five hundred miles on eight days' reduced

rations; it lost eight men—one killed by the enemy, seven

dying of disease.

Died of disease:

Private Charles Rainwater, company C, November

27, 1899; *¹

Private Shelby Taylor, company C, December 7, 1899;

Private George Lehfield, company C, December 17, 1899;

Private Arlington Mayse, company H, January 3, 1900; *²

Private Mathew McNulty,company B, January 5, 1900;

Private Samuel D. Long, company C, January 15, 1900; *³

Private William H. Coleman, company H, January 18, 1900.

*¹ Incorrectly recorded as Private Charles

Rosewater in the 1904 Regimental history

*² Incorrectly recorded as Private Arlington Mayne in the 1904

Regimental history

*³ Incorrectly recorded as Private John Long in the 1904

Regimental history

Brigadier General Henry Ware Lawton The 22nd Infantry had served

under Lawton in Cuba, He led from the front, and was

killed by an enemy sniper Lawton was the

highest-ranking U.S. military officer He was a Brigadier General of

Regulars and Photo from the National Archives |

|

Home | Photos | Battles & History | Current |

Rosters & Reports | Medal of Honor | Killed

in Action |

Personnel Locator | Commanders | Station

List | Campaigns |

Honors | Insignia & Memorabilia | 4-42

Artillery | Taps |

What's New | Editorial | Links |