![]() 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry

1st Battalion 22nd Infantry ![]()

LZ Buffalo

LZ Buffalo March-April 1971

In 1971 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry (1/22 Infantry) was based at Tuy Hòa on the coast of the South China Sea. Near the end of March 1971 my Company, Company C (Charlie Company), was directed to return to the interior of the country near An Khê, to act in concert with 1st Squadron 10th Cavalry (1/10 Cavalry). Charlie Company 1/22 Infantry was assigned to conduct a search and destroy operation in the mountains around LZ Action, east of Pleiku. Since I had a little over a month left to go on my active duty commitment to the Army, and would thus be leaving Vietnam and going home soon, I really didn’t want to take any more risks, and especially didn’t want to go back into the mountains where danger most certainly existed. Extreme selfishness took over me, and I worked hard to beg, plead, cajole, con and threaten my way out of going with my platoon on that mission.

However, within a day or so of securing permission to not go on the mission, I was informed I would not be staying in the relative safety of the Base Camp at Tuy Hòa, but would be going to the forward support base of LZ Buffalo at An Khê, to help handle the re-supply for the Company while they were out in the field. I was highly upset and felt I shouldn’t have to do that, because I was a short timer. I went to see First Sergeant Gray in his office, to make my displeasure apparent, and demand I be allowed to stay at Tuy Hòa. He told me in no uncertain terms, to quit complaining, and that I was going to LZ Buffalo, to be part of his re-supply detachment. In hindsight I realize that Headquarters Platoon was remaining at the Base Camp at Tuy Hòa, to carry out administrative functions for the Company. Therefore First Sergeant Gray had very few men available, to accompany him to LZ Buffalo and perform the function of the re-supply detachment. Since I would not be going into the mountains with my platoon, it was only right to utilize me as a member of the forward detachment at LZ Buffalo.

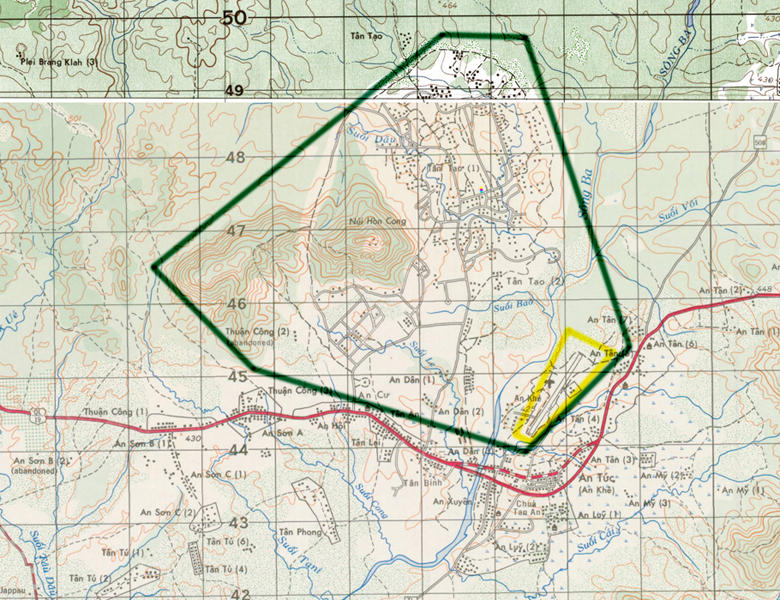

Dark green lines indicate

the approximate area of Camp Radcliff at An Khê.

Yellow lines indicate the approximate boundary of LZ Buffalo.

Red line snaking across the map from left to right is Highway 19

(QL 19).

The dark green line

approximates the total area that was encompassed by the huge

complex that was Camp Radcliff,

but does not necessarily mean that there was an unbroken

perimeter line of bunkers and towers in that green line.

The Camp was a series of irregular perimeters which together

constituted that large area known as Camp Radcliff.

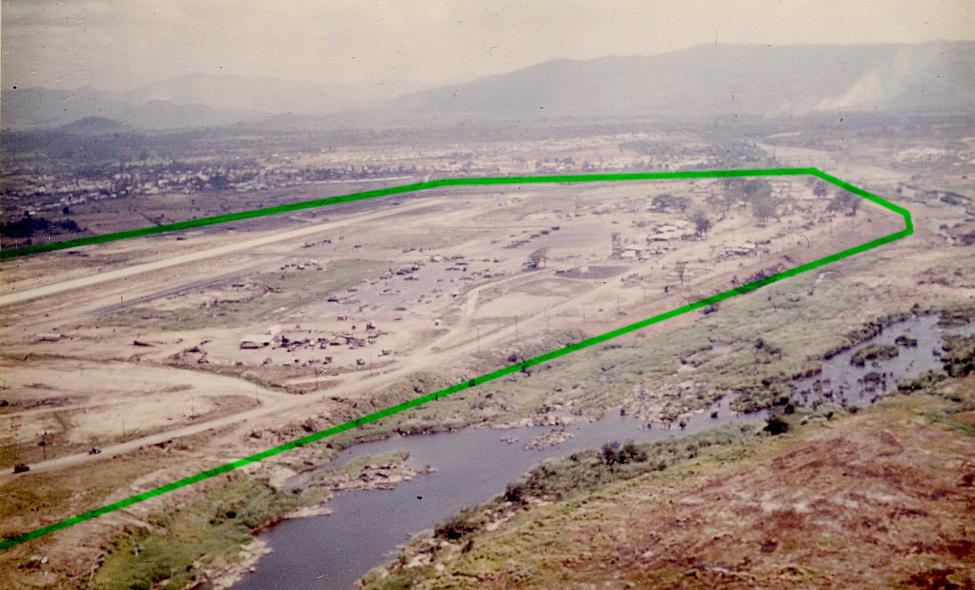

Aerial view of LZ Buffalo

in 1971, with north at the top of the photo.

Green lines indicate the approximate boundary of the compound.

The airstrip is inside the

green lines on the left. The river is outside the green lines on

the right.

The 1/10 Cavalry Headquarters was in that clump of trees in the

upper right, inside the green lines.

The southern end of the

boundary of the compound is just past the end of the airstrip,

out of the photo to the left.

Photo taken while flying over LZ Buffalo in a Huey helicopter in either March or April 1971.

LZ Buffalo was a relatively small compound, compared to most Army Base Camps, and was laid out alongside the airstrip at An Khê. Its official grid coordinates were BR 476444. It had once been part of the huge, sprawling military complex that included Hon Cong Mountain (Núi Hon Cong). That complex had been known as Camp Radcliff, and had originally been built as a base camp for the 1st Cavalry Division in 1965/1966. In 1969 Camp Radcliff became home for the 4th Infantry Division. When the 4th Infantry Division left Vietnam in December 1970 Camp Radcliff had been mostly dismantled, and small chunks of the large base, as isolated perimeters, were all that was left of it. Buffalo was one of those chunks.

Buffalo’s perimeter went around the airstrip and made the compound a long, skinny affair. The 1/10 Cavalry had their headquarters and motor pool next to the trees on the east side of the compound, by the river. D Troop of the 1/10 Cavalry (which was their aviation asset and consisted of Shamrock Guns, Shamrock Scouts, and Shamrock Blues) had a presence at the helipad area from time to time. By the old French control tower there was an Army Medical unit which most likely was the 8th Field Hospital before it moved to Tuy Hòa. The 2nd Platoon of the 560th Military Police Company had a shack near the Cavalry headquarters, and it was not unusual to see one or two of their V-100 (M706) armored cars parked in front of that shack. There was also a unit of tracker/scout dogs based out of Buffalo, the 78th IPCT (Infantry Platoon Combat Tracker). Their dog cages were right next to our re-supply detachment's area. If I had to guess I would say there were no more than 500 to 600 American soldiers permanently stationed at Buffalo in March and April 1971.

The runway of the airstrip was long enough to handle four engined C-130 cargo planes, and while we were there quite a number of them landed, unloaded, and then took off again. Twin engined C-7 Caribou cargo planes also flew in and out of Buffalo, and it was not unusual to have one C-130 or C-7 sitting on the taxiway while a second landed on the runway. As far as I can remember, no C-130 or C-7 aircraft stayed overnight. For a time a Cessna O-2 FAC (Forward Air Control) aircraft was parked at the end of the taxiway, near the tent and quonset hut that was the location of the detachment in charge of the runway operations. An O-1 Bird Dog FAC or spotter aircraft was parked at the end of the taxiway for a short time while I was there. As far as I can tell, no aircraft were permanently based out of Buffalo, and only individual small planes and sometimes a few helicopters would actually spend the night or longer there.

In our detachment there were about seven or eight of us from my Company there at any one time to handle the re-supply for the Company. First Sergeant Gray was in charge, I was one of two Sergeants on the team, and there were usually about four or five enlisted men. We occupied two general purpose tents in about the middle of the compound, in between the Cavalry headquarters area and the airstrip. Even though I was not humping the boonies, I lived out of my rucksack, in which I had packed all the personal items I needed. We had a number of conex containers, or boxes, which held spare weapons and supplies for the Company, and had access to a small quonset hut and a small tin sided storage building holding more supplies. We also had one or two jeeps and trailers. We ate in the Cavalry mess hall over by their headquarters, and were not required to pull guard duty on the perimeter line.

Before we were able to obtain

Vietnamese civilian workers to work for us, we had to burn the

barrels from our shitters. It was the only time I had

to burn shit, and I did it at least two times, before we got some

Vietnamese to do it for us. We also got Vietnamese women (hooch

maids) who

washed our clothes and hung them on a clothesline next to our

tents to dry. We had a small bunker dug into the ground a short

distance from our tents, with a sandbagged PSP (Pierced Steel

Planking) roof, which was our shelter and fighting position in

case of an attack.

Area

for re-supply detachment of Company C 1/22 Infantry at LZ Buffalo

March/April 1971.

Our two tents are in the left foreground, with our laundry drying

on the clothesline. Our jeep is next to the tents.

On the other side of the trees in the upper left is the 1/10

Cavalry Headquarters.

I took this photo while standing on the roof of our little

bunker.

Life for us during the daytime hours was pretty easy and mundane. Every four days we made sure that enough cases of c-rations and any other supplies got put on helicopters and sent to the Company out in the field for their re-supply. The other Sergeant and I oversaw that part of our operation. (He was from a different platoon than mine. I can’t remember his name, but I think it was Taylor, so for this narrative I’ll call him Taylor.) Taylor and I would help to load everything in the jeep and trailer, then direct a couple of enlisted men to take the jeep over to the helipad, where they would load it all into the helicopters that would bring it to the Company out in the mountains around LZ Action. As many trips to the helipad as it took, to get everything loaded, were made using the jeep. We also sent whatever other items the Company requested or needed at whatever time they needed it. For instance, if the Company had a machine gun or radio that was broken, they sent it back to us at Buffalo by helicopter. We took a spare from one of our conex's and sent it out to them by helicopter.

Company personnel came and went through our detachment, as individual soldiers came to Buffalo for medical attention, or caught flights to Tuy Hòa to go on R&R, or rotate home because their tour was over. We could go over to the Medical unit and watch Hollywood movies on the nights when they showed them. At that unit they had made a screen out of plywood, painted it white, and constructed crude benches in rows before the screen. They would show movies on that screen at their “outdoor theater” every so often. One night, as I sat watching the movie "Airport" with about a dozen other guys, a red tracer round came flying over the top of the movie screen. I jumped up, ran back to my tent, threw on my steel helmet and flak jacket, grabbed my rifle and a bandoleer of ammo, and ran back to the "outdoor theater" to finish watching the movie. I got a couple of funny looks for doing that, and answered them with a declaration of "I'm short!"

There was some kind of South Vietnamese Army (ARVN) presence in the area. I don't know what unit, or how large the unit was, but I remember them being to the west of the airstrip, still in the general area that had once been part of Camp Radcliff, and within sight of Buffalo. Almost immediately after locating to Buffalo we got word that the ARVN's had captured some prisoners, and that from interrogation of those prisoners, and their own reconnaissance, the ARVN's determined that there were two Companies of North Vietnamese Army (NVA) or Viet Cong Infantry on the move somewhere in the vicinity of LZ Buffalo, with the intent of carrying out some kind of attack, but against what or whom they did not know.

On the second night we were at Buffalo we took incoming fire. The enemy fired a few bursts from an automatic weapon into the compound, then several hours later repeated the same. Two nights later three or four mortar or rocket rounds were fired into the compound. The next night we received more automatic weapons fire several times throughout the night, against which some of the guys on the perimeter returned fire of their own. A couple nights later we received a few more mortar or rocket rounds, and more isolated small arms fire at different times during the night. Then a night with no fire and then another night with some incoming small arms fire. Some or all of that could have been a probe or test of our defenses by the enemy, or a rehersal or preparation for an attack. This went on for over a week, and the result of it all was to cause some of us to lose sleep, as we would often stay awake for most of the night after we took fire.

On the night of April 3, 1971 we took only a few shots fired at us. I had lost considerable sleep from the nights before, so that night I went to sleep easily, as I was quite tired. After so many nights of taking some kind of fire, by that time I was sleeping with my fatigues on, my loaded rifle lying next to me in the cot, along with a couple bandoleers of magazines under the rifle, my helmet and flak jacket at the head of the cot, and my boots on my feet, though not laced up. First Sergeant Gray was not there, as he had gone out to LZ Action during the day and was staying overnight at either LZ Action or LZ Schueller. Therefore, Taylor was technically in charge of our detachment while Gray was gone, as Taylor had date of rank over me by a couple of months.

As the night turned into the next day, April 4, I was asleep on my cot in my tent, and was having a nightmare in which the world was blowing up around me. Just past midnight I was awakened from that nightmare by Taylor, who was shaking me and yelling “Get up, that’s incoming!” I opened my eyes to the world really blowing up around me, and the loud booming of explosions in my ears, as I quickly adjusted my senses to becoming awake and alert. Obviously my "nightmare" had actually been me hearing and feeling the explosions around me, but my body and mind refusing to wake up and trying to remain asleep.

In an instant I was able to gather my rifle, bandoleers, helmet, and flak jacket, exit the tent, and run to our bunker which was not far from our tents. The other guys were already at the bunker, and all six of them were inside the little bunker that was built to hold two or four at the most. I crouched on the ground outside, right up against the bunker. I remember that I hurriedly bloused my trousers into my boots and laced my boots up tight. Looking back at it now, I find it curious that I was concerned with doing that, while being under fire. I should have been hugging the ground instead. It was an Infantryman's reflex, I guess, to make sure my boots were secure.

The enemy was firing mortars into our compound, and though most rounds appeared to be hitting in the Cavalry area, others were landing elsewhere too. Some were also hitting around us and several hit somewhat close to us. I haven’t been able to get the after action reports or daily staff journals for that date, so I don’t have an official or accurate record of how many mortar rounds were fired at us that night, but at the time it sure felt like a lot. I would find out later that some of the explosions that came from the Cavalry area that night were satchel charges being thrown or set off by enemy sappers.

Each explosion lit up the night sky like a giant strobe light. Any that were reasonably close shook the ground as well, and the closer they were, the louder the “boom” they made. A couple of mortar rounds hit within fifty feet or so to us, and since I never had mortar or rocket rounds land that close to me before, those couple produced an effect I had never experienced. Just before I heard the explosion, perhaps a millisecond before, I felt my stomach contract or move inward, as if it sensed what was about to happen, and was trying to withdraw or hide from it. Maybe what I experienced was some concussion from the explosions, and maybe the concussion travelled an instant faster than the sound did. As close as those couple landed, I was surprised to have not been hit by shrapnel. Perhaps they didn't strike close enough to us for that. Perhaps they did, and I was just lucky.

There was some small arms fire coming from the east side of the compound, the side along the river. Then suddenly the east, and the northeast side of the perimeter erupted in a cacophony of rifles and machine guns all firing at the same time. Mixed in with that were a few smaller explosions of grenades and RPG’s (Rocket Propelled Grenades, which we called B-40 rockets). We couldn’t see that side of the compound, because there were tents, trees and buildings between it and us. From the sounds it appeared a large firefight, probably a ground attack, was happening on the eastern side, and especially at the northeast end. Maybe it was an attack by those two Companies of enemy Infantry that the ARVN's had warned us about. Or maybe it was a larger force than that. Soon added to that northeast end and east side was the sound of tracked vehicles and heavy machine guns, .50 caliber guns obviously, indicating that one or more of the Cavalry's APC's (Armored Personnel Carriers) was taking part in the fight. There were also different sounding “booms”, which apparently came from the cannon of one or more of the Cavalry's tanks. From the immensity of the gunfire, I expected at any moment to see hordes of enemy soldiers come running across the compound at us.

As it continued and escalated, the scene was extraordinary. Explosions were coming from the Cavalry area. Mortar rounds were landing inside the compound, the flash of their explosions lighting up the night, their loud “booms” piercing the air, the ground shaking from those that hit close to us. What sounded like dozens of rifles and machine guns were firing without letup on the east side, and especially the northeast end of the perimeter. Added to that was the “blang!” slamming sound of grenades and the “bam!” of B-40 rocket propelled grenades. Red and green tracers appeared at various places, and a burst of green ones came flying across the compound, from our front to our rear, just to our left, the cracking sound they made echoing in our ears as they passed by us. There was the sound of engines revving, and tracked vehicles moving about. At least one tank was firing its cannon. Heavy machine guns thundered, their sound louder than other automatic weapons. A few flares were popping above and drifting down, their smoke trails visible as they descended, their flickering glare illuminating the surreal scene around us. Men were shouting. The staccato popping of small arms fire was never ending, and above all the commotion someone was yelling for medical assistance. His plea was loud, and could be heard distinctly, against all the other noise. The fear, emotion, and urgency in his voice as he screamed “Medic!” over and over sent a chill through our bones. Hearing that plaintive cry, Taylor and I looked at each other and very seriously Taylor said “When I get hit I hope the guy who calls for a medic for me has as much balls as that guy.”

I had been shot at a number of times before, but it had always been by just one or two of the enemy. I had also fired back at bad guys who were shooting at me, but only did that a couple of times, and those incidents had been brief in duration. I had been mortared before, but that was only a few rounds fired at the most, and not the seemingly incessant pounding that this was. I had been under rocket attack, but even that had ended after only a reasonably short time, with relatively few being fired. Everything unfolding around me this night was making all I had seen before this seem like nothing. The ferocity of this attack, coupled with the striking visual panorama created by it because it was a night attack, staggered my imagination and filled me with a terrible sense of dread.

Though I was protected on one side by the bunker I was next to, I was actually crouched out in the open and exposed on three sides. My vulnerability was apparent, and the situation around me was overwhelming. The guys in our bunker were just as impressed by it all and appeared to be just as scared as I was. It seemed we had been attacked by a large enemy force and the thought that immediately overpowered my mind was that we would be overrun and all of us killed.

I had actually come to Vietnam thinking I would not live through the experience. Just before I entered the Army, Kenneth Prejean, my best friend since we had both been toddlers, had been killed in Vietnam. We had grown up together and had lived next door to each other for about ten years. As kids our lives were intertwined just about every day. Even after we were later separated, when my family moved to another town, and we saw each other only a few times each year, we picked up the conversation right where we left off, every time. Though we were only related as distant cousins through the Prejean family, we were true brothers in every other sense of the word. Kenny was killed while serving in 2/7 Cavalry on May 1, 1969 during an attack at LZ Jamie. Eight days after he was killed, on Friday, May 9, 1969 I watched him being placed in his grave in New Orleans. Three days after his funeral, on Monday, May 12, 1969 I went into the Army. Kenny was always braver than me, stronger than me, and understood life better than I ever could. I always felt that if he couldn't make it through the war, then for sure there was no way I could. So I came to Vietnam believing I was going to die here. I had been in Vietnam for seven months now, and every time I had got shot at, I thought “this could be the time I get killed.” But this night, at LZ Buffalo, facing the terrible spectacle of the world unravelling around me, I didn't just think I could get killed, I truly believed this was the night I was going to die.

From the moment Taylor had awakened me, and I had rushed out of the tent to the bunker, I had been afraid, with the fear growing as the attack intensified. Now added to the fear was the knowledge that I was about to die. I got some idea of what they say a drowning man experiences, as my life flashed before my eyes. In my mind I had an early memory from my childhood, followed by a lightning fast series of isolated memories through the years, of events which all led up to this moment in time, and a horrible awareness that all those memories, all those events, the sum total of my life, ended right here, right now.

I thought of God and what I might be facing for eternity, and in that moment I talked to God. I didn’t ask Him to get me out of this mess, and promise to be a good boy if He did. I knew I was going to die this night, and nothing was going to stop that. I simply and sincerely told God that I knew I had been a selfish jerk for much of my life, and that I was really sorry for everything I had done that was wrong or stupid. I told Him that I hoped He would send me to heaven, but I knew that He would give me the reward I deserved, whatever that would be, and I surrendered that fate to Him. I’m not sure I had ever been that humble in my life before that, or have ever been that humble since.

Talking to God turned out to be a good thing to have done. After that I was still scared, and my heart was still pounding, but I was no longer distracted with dying, and my mind then became occupied with what I needed to do, to deal with the present situation.

I examined our surroundings, and realized that to our front, in other words, to the east, there was about 50 yards between our bunker and the trees. On the other side of the trees was the Cavalry Headquarters area. That area, and the area to our left front, the northeast, were the areas which involved the heaviest gunfire. Most of the explosions were coming from our front and our right front. Behind us to the west, it was about 150 yards or more to the edge of the airstrip, which gave a total of about 200 plus yards of open area or more to our back and the west side of the perimeter. No mortars were landing near the airstrip, and no gunfire was heard in that direction, so it did not appear to be an object of this attack. We also had a short line of concertina wire, close to our bunker, on the side between us and the airstrip, which made it difficult for anyone to rush at us from that direction. Therefore the area to our back did not appear to be of concern. To our right, or south, there was about 75 yards or more of open ground between us and the Medical unit. Relatively few explosions were coming from that area. To our left was a few hundred yards or more of open ground to the north perimeter of the compound. No explosions or gunfire was occurring directly on that side, except for the very northeast tip.

I didn’t like the idea of our bunker being so out in the open. It meant the enemy had to expose themselves to some open ground to get to us, but it also meant that our bunker stood out as a target. I felt that one well-placed B-40 rocket could take out the bunker and get us all. However, the bunker is where we were, and we needed to defend it as best we could. As the attack continued, with the ruckus of all those guns firing to our front and our left front, and the mortars still landing to our front and to our right front, I left the bunker, ran to our weapons conex, got an M-60 machine gun and a 250-round steel can of ammunition for it, and brought that to the guys in the bunker. They took it, and one of them loaded the gun and pointed it outside the bunker, ready to fire if needed.

The mortars and explosions continued for a while, and then stopped, and the gunfire died down considerably. I looked at my watch and the time was about 12:40. We had been under attack for over half an hour. It had seemed longer.

About ten minutes later everything was still reasonably quieted down, compared to the vicious tumult it had been for a while. I was still scared, but my heart was not pounding like it had been doing before. I was surprised we had not seen the enemy come charging directly at us, but knew that could still happen, as this might not yet be over. I remained uncomfortable with our position being so open and alone, so I looked at Taylor and the guys, and said to Taylor “How about you and I going over to the Cavalry and telling them we have seven Eleven-Bravo's (Infantrymen) here, if they need us to fill a hole in the perimeter line, or use us as a quick reaction force?” I could tell by the look on the guys’ faces, including Taylor’s, that they thought this was not a good idea. So I said “Hey, it’s better than sitting here waiting for the dinks to come and get us.” They looked more understanding of that, but still didn’t jump to agreement. I leaned close to Taylor and in a low voice told him “C'mon man, you and I need to go find out what’s going on.” He nodded and came out of the bunker. Once again I had broken my rule of self-preservation in Vietnam. That rule said if it didn’t happen in a three foot circle around me, then don’t go see what it was. But somehow going over to the Cavalry and offering to get into the fight before it came to us, seemed to me like the right thing to do at the moment, even if the other guys weren't enthusiastic about it.

There was still some firing going on at the perimeter, though it was quite reduced from what it had been before. Flares were still popping overhead and casting their eerie glow, creating areas of light and shadow across the compound. Taylor and I headed over to the Cavalry area. We went past the trees, turned the corner around a building, and came into the courtyard formed by the Cavalry Headquarters Company buildings. The sight that greeted us was not good. There on the ground, sitting, kneeling, crouching or lying down up against the side of the buildings were Cavalry personnel. Why weren’t they out on the perimeter line, helping to fight off the attack? The look on many of their faces told us why. It was a look of extreme fear and even panic. We asked a couple of them where their officer was and they didn't know.

We found a young officer. I told him we were handling the re-supply for 1/22 Infantry, and asked him what was going on. His reply did not make sense. In the light of the flares overhead, the fear and confusion on his face was apparent. He was stuttering when he talked, and somewhat incoherent. So Taylor tried asking him questions that were more to the point, something like “How many enemy are there?" and "Have they broken through the perimeter?” and the officer kept repeating that he didn’t know, and mumbled something about explosions and a lot of firing. I looked at the officer, then looked around again at the men on the ground against the buildings, and I thought to myself "what the hell are they doing?" I realized if Taylor and I had been enemy soldiers, then when we came around that corner we could have killed half of these guys before they knew what hit them. And their demeanor told me that most of them would probably have done nothing to even try to prevent that from happening. I could feel the fright and hysteria in these soldiers. It was as if it was in the air and contagious. This was a bad situation and I wanted no part of it. I told Taylor “These people are all just sitting around waiting to die. Let’s get out of here” and he agreed.

We went back to our little bunker and told the guys we were just going to stay at our bunker all night. They were quite relieved to hear that. I remained outside the bunker and Taylor now stayed outside of it as well. I was pretty upset and mad about the Cavalry guys. Many years later as I told the story to a good friend, who had served two tours in Vietnam, the second tour as a Recon Platoon Leader in the 101st Airborne, he put it in better perspective. He told me to not be so hard on those guys I saw trapped by their fears and huddled against those buildings. He explained that most of the soldiers I saw were for certain from the Headquarters Company of the Cavalry. They were clerks, typists and other rear echelon personnel, most of whom had never been trained and motivated as Combat Arms personnel, and had probably never been shot at, let alone experienced combat of any kind. If the beginning of the attack had so overwhelmed me as to give me the impression I was about to die, with my position being removed some distance from the perimeter, then I can only imagine what they felt, with their position being a lot closer to the action. So I came to feel sorry for those poor guys that night. They must have been scared out of their minds. I could relate to that.

The lull in the attack continued, then about twenty minutes after the mortars stopped, they started up again. The night was lit up by the flashes of their explosions, their “booms” split the air, and the ground shook again when they landed close. The firing on the east side of the perimeter increased, though not as profuse and intense as it had been before. At one point we saw someone run across the inside of the compound, between us and the Cavalry area, moving in a direction from our left to our right. He came out of the darkness, ran through the circle of light cast by a light on a pole, then disappeared into the darkness again. I immediately identified him as an enemy soldier by the weapon he was carrying. It's odd, but it did not register in my mind that his weapon was an AK-47. However, I could clearly see that his weapon had a curved magazine. None of our American weapons had curved magazines, so right away it connected with me that he was a hostile enemy personnel. He ran through another circle of light, and I leveled my rifle to fire at him, but he was lost in the darkness again before I could shoot.

The mortars, explosions, and firing carried on for a while longer, and then finally the mortars and explosions quit altogether. Although it didn't stop completely, the firing died down to next to nothing. A couple of minutes after the mortars and explosions stopped I looked at my watch and I remember the time being close to 1:30. For the rest of the night there were no more explosions. Continuing until dawn, nervous G.I.’s shot sporadically into the dark here and there, but the real action that night was over, and had lasted altogether for about an hour and a half, with the intensity of it diminishing for about fifteen to twenty minutes in the middle of that time. Our little group stayed at our bunker until the darkness of night began to lighten into a misty, fog shrouded dawn. Only then did we leave the bunker and start to move around, examining our tents and belongings to see if anything was hit or damaged. None of us from the re-supply detachment for Company C 1/22 Infantry at Buffalo were wounded or injured that night, and none of us from the re-supply detachment had fired any of our weapons at any time during that attack. Though we had not taken part in any of the fighting, we all shared the relief of having survived a particularly frightful attack.

LZ Buffalo attack of April 4, 1971 - North is to the right

A

indicates the location of our re-supply detachment for Company C

1/22 Infantry

B indicates areas of exchange of heavy groundfire

C indicates Cavalry motor pool where the enemy sappers blew

things up

The buildings just below A in the photo are in the Cavalry Headquarters area

The

airstrip can be seen in the center of the photo

The river can be seen in the bottom of the photo

Photo of AH-I Cobra of D 1/10 Cavalry flying

over LZ Buffalo taken in late 1970 or early 1971 by Tom Wilson of

1/10 Cavalry.

From the D

Troop 1st Squadron 10th Cavalry

website used by permission

Yellow letters and arrows added by Michael Belis

Just before daylight came,

the Cavalry lined up a number of tanks and APC’s right

behind our bunker. Soon after daylight they moved out and made a

sweep across the inside of the compound, looking for enemy who

might be inside the perimeter. An APC with a flame thrower

mounted on it went around burning brush in places where an enemy

might be hiding. A couple of hours after that we got word that

the Cavalry had found a few dead and a few live enemy soldiers.

Two or three of our guys went to see them. When they returned

they told me they had seen several dead enemy and several live

enemy too. The way they described the appearance and manner of

the live enemy soldiers made me think the sappers must have been

loaded up on drugs to make the attack and were probably still

under the influence. Apparently what I had thought was a full

scale ground attack at the northeast end of the perimeter was

just a diversion and covering fire, so the sappers could get

inside at the other end of the perimeter and do their damage.

LZ

Buffalo in the early morning mist/fog as daylight begins to

break, several hours after the sapper attack of April 4, 1971.

I took this photo facing toward the airstrip to the west.

In the

upper right center of the photo is the bunker where me and the

re-supply detachment were during the attack.

The line of concertina wire can be seen just beyond our bunker to

the left. Tanks and APC's from 1/10 Cavalry are lined up

behind our bunker and are about to make a sweep across the

compound.

The enemy penetrated the perimeter on the east side, coming across the river which was shallow at that time of the year. The sappers who got inside the compound destroyed or damaged numerous vehicles in the Cavalry’s motor pool. They also destroyed the one room building that was the Chapel, which was close to the motor pool. The Cavalry lost two men killed during the attack. I have no details on the possible number of wounded.

Specialist 4th Class Thomas Lee Blatz was a member of C Troop 1/10 Cavalry, and was one of the men who was killed that night. He was in the Cavalry's motor pool when the sappers got inside of it and blew up vehicles. A remembrance left for him on the The Wall-USA website described his death in this way:

“Ned Ricks Commanding Officer - Tommy was killed, when NVA sappers entered the compound through barbed wire. When they started blowing up vehicles with satchel charges, he defended himself and his comrades, with a pistol, until his death.” ¹

|

Specialist 4th Class Thomas Lee Blatz C Troop 1/10 Cavalry Killed In Action at LZ Buffalo April 4, 1971 Photo from the |

Private First Class Robert William “Cosmo” Homschek was a member of Headquarters Troop 1/10 Cavalry, and was the other Cavalry trooper who was killed that night. Apparently he was in a bunker on the perimeter line on guard duty and was killed when a sapper threw a satchel charge either into the bunker or near it.

I didn’t know Cosmo personally but I knew his name. While at LZ Buffalo we ate in the mess hall of the 1/10 Cavalry. Since it only accommodated a small number of soldiers at a time there was always a line outside along the wall of the little wooden shack at mess time. Soldiers would write graffiti on the wall as they waited to get into the mess hall. Cosmo’s graffiti caught my eye because he was a short timer like me and he wrote his name and how many days he had left to go before going home. Each day he would line out the number of days and write a new number that would be one less than the day before. After the attack someone drew a line through his name and next to it wrote the letters KIA for Killed In Action. As I remember it, Cosmo was due to go home a couple of weeks before me, so he died with less than a month to go in Vietnam.

|

Private First Class Robert William "Cosmo" Homschek Headquarters Troop 1/10 Cavalry Killed In Action at LZ Buffalo April 4, 1971 Photo from the |

Life for us at Buffalo after the attack of April 4 mostly settled back down into the more or less mundane. For the rest of the time I was there we took small arms fire only a few times, and never took any more mortar rounds or sapper attacks.

One day I was right outside the Medical unit, for some reason which I now can't remember. A helicopter landed nearby, and two wounded, bloodied, and bandaged enemy soldiers were brought from the helicopter by stretcher and carried into the Medical unit, while under guard by a couple of American soldiers. I recognized the enemy's uniforms immediately, as I had first encountered those when out in the boonies back in September 1970. The pale green color of their North Vietnamese Army uniforms was quite different from the olive drab coloring of ours and the South Vietnamese. One of the wounded soldiers was wearing a complete North Vietnamese Army green uniform and was not moving. The other was wearing a North Vietnamese Army green shirt and black pajama shorts, and was wincing and writhing in pain. I watched them being brought into the Medical unit but did not hang around to witness their final disposition.

Being Infantry, our uniforms were, for the most part, devoid of ornamentation. At Buffalo we noticed a lot of the Cavalry guys walking around wearing brightly colored pocket patches on their jungle fatigues. Several of us decided we deserved to have something equally as distinguished for our unit. There was a tiny shack in the Cavalry area that served as the tailor shop for the base. It was operated by a Vietnamese, who could create name tapes for uniforms, and fabricate colorful unit patches. He had on display in his shop several unit patches he had created for the Cavalry. We picked one we had seen a lot of the guys at Buffalo wearing, and asked the tailor to create a similar patch for our unit.

The tailor told us he would only make the patch if we bought several at a time. He wouldn't sell us just one patch, we had to buy a minimum of six of the same design. There were three of us who went to the tailor shop together, and each of us bought the minimum of six patches, so there was a total of eighteen examples of our design made. The design we chose to copy was for D Troop of the 1/10 Cavalry. It consisted of their red and white Battalion guidon embroidered on an olive drab disc. We wanted our blue Battalion guidon done the same way. The whole episode ended as a comedy of errors. The tailor used a light blue color for the guidon instead of the regulation dark blue. That was okay with us, as light blue was the color of our Infantry shoulder cord, and also the color of the backing of our Infantry collar discs. However, somehow, the placing of the numbers in the guidon got transposed, and were embroidered in the wrong place. The "22" should have been at the top of the guidon and the "1" should have been at the bottom, but instead those numbers were placed the other way around. We accepted the patches the way they were, oblivious to the fact that we didn't have patches for 1/22 Infantry but instead had patches for 22/1 Infantry.

Above: The patch for D 1/10 Cavalry, |

-------------------- |

Above: The patch for C 1/22 Infantry |

At some time during our stay at LZ Buffalo, Ralph “Bo” Bonnema arrived at Buffalo from Tuy Hòa, with a big sack of mail for the Company. Bo had been with the Company for almost a year. He and I had served together in 3rd Platoon on a search and destroy mission in the boonies back in September/October 1970. Bo was one of the first friends I made after joining the Company. After that mission he left 3rd Platoon, took a job as a postal clerk with Company Headquarters, and hung around with the Headquarters guys instead of hanging around with us in 3rd Platoon. I hadn’t seen him in a while so it was good to see him. We all told him that he wouldn’t want to stay at Buffalo long, as it was a dangerous place to be. He was a short timer like me, and was due to leave Vietnam about the same time I was, so after we told him how bad Buffalo was, he didn’t stay long with us before returning to Tuy Hòa.

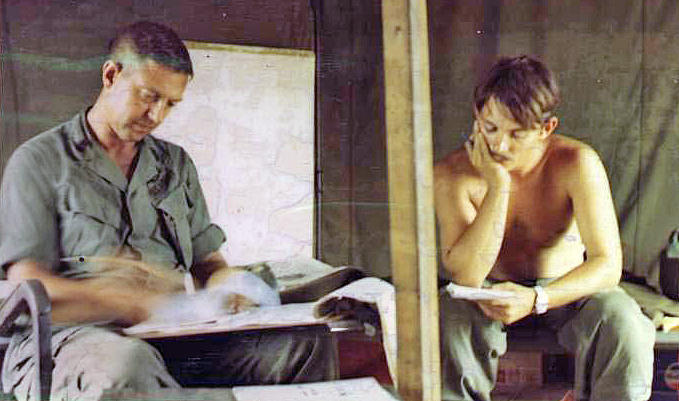

First

Sergeant Gray on the left, me on the right, in our tent at LZ

Buffalo as we determined the supplies

we needed to get ready for a re-supply for the Company April 1971

Photo by Ralph "Bo" Bonnema Company C 1/22 Infantry

For one re-supply the Company was going to receive a change of uniforms. I don’t remember how the uniforms got from Tuy Hòa to us, or if they came from our Headquarters back at Tuy Hòa at all. They may have been from a uniform pool, as many times since I had been with my Company, we had shared a uniform pool with the 173rd Airborne, who operated in the same area of operations as us. For some reason, at least part of this re-supply was going to be done by vehicle. While Taylor stayed at Buffalo with the guys from the re-supply detachment, I went with First Sergeant Gray by vehicle to LZ Action, a forward firebase right on Highway 19, just outside the Mang Yang Pass. We travelled on the highway in a small convoy of vehicles, our vehicle being an M-548 Ammo Carrier from the 1/10 Cavalry. The M-548 was a fully tracked vehicle based on the chassis of an M-113 APC. Gray rode in the cab with the driver while I rode in the back, in the cargo area.

On this M-548 vehicle there was an M-2 .50 caliber machine gun mounted above the cab, where I could operate it from the cargo area. There was also a pedestal mount for an M-60 machine gun, but no gun. Before we started out I had asked the driver where the ammunition for the .50 caliber was. He told me not to worry about it because the gun didn’t work anyway. It boggled my mind to believe these Cavalry guys would take a vehicle out into the field with a main gun that didn’t work. It seemed to me they could have turned the gun into their armorer to get it fixed, or replaced it with a gun that did work. Obviously then, I would have to rely on my rifle with two bandoleers of magazines, as our individual weapons would thus be our only defense for that vehicle should we run into contact with the enemy. Our little convoy of vehicles left Buffalo and headed down Highway 19 to LZ Action. At LZ Action we found a number of guys from our 2nd Platoon were there at the firebase. There were also a few guys there from 3rd Platoon, my platoon. We loaded up more supplies to take to our Company.

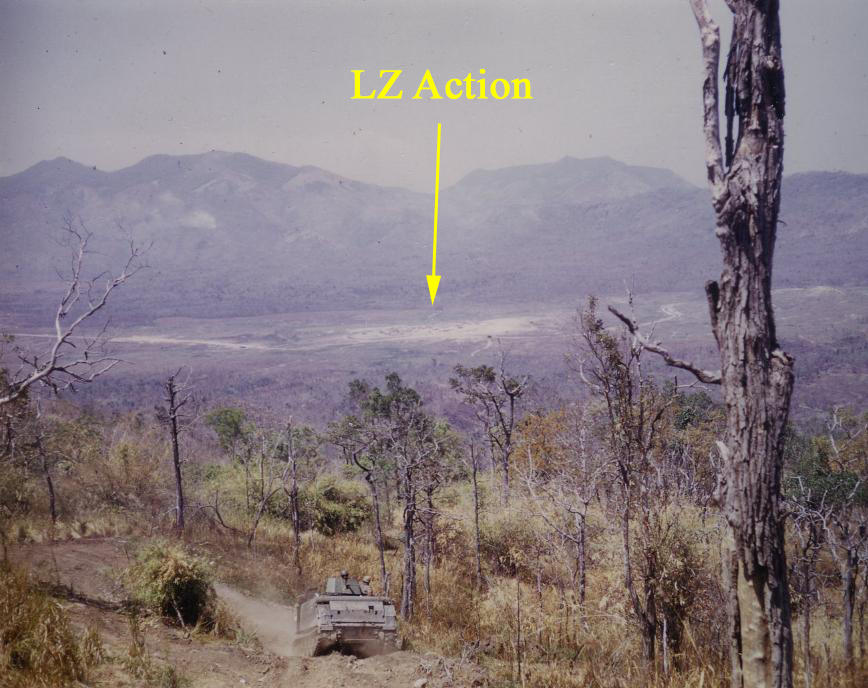

LZ Action April 1971

The

M-548 ammo carrier track from 1/10 Cavalry, on which we took a

re-supply to Company C in the mountains

in the area around LZ Action, April 1971. Guys from 2nd and 3rd

Platoons of my Company are loading supplies

and ammunition in the cargo area of the vehicle. The duffel bags

in the foreground contain some of the

clean uniforms for the Company and will be loaded on the vehicle

as well.

From LZ Action several APC’s from the Cavalry led our M-548 vehicle into the mountains to the west of the firebase, to where our Company was waiting for the re-supply. When we got to the Company I was less than impressed with what I saw. They were set up in a semi-permanent position on a mountain top, and had dug bunkers into the terrain features, reinforcing the bunkers with filled sandbags. There were a couple of large pits with sandbags around their edge, indicating they may have had the Company's mortars set up, but the mortars were not in place when I got to them. There was a lot of litter and debris and empty sandbags all around the position, as if they had half dismantled everything. The entire situation looked very unorganized, and not very defensible. I was glad I had not gone out here with them on this mission.

LZ Action April 1971

M113

Armored Personnel Carrier of 1/10 Cavalry moving into the area

west of LZ Action. The firebase itself can be seen in the

background,

with Highway 19 winding around it. The Mang Yang Pass is to the

left. Some of the defoliated vegetation is beginning to come

back.

I took this photo while riding on the back of the M-548 ammo

carrier track, as we brought a re-supply to the Company out in

the

mountains around LZ Action.

After issuing the re-supply, our vehicles headed back down the mountain to the firebase. We stayed at LZ Action for a couple of days. One of those days the Company out in the mountains saw some enemy soldiers on a mountain top across the valley from the one they were on. There was no contact with the enemy, or firing at them because they were too far away. The Company called in an airstrike on that opposing mountain top, and from LZ Action we watched the bomb hits, as a couple of F-100 jet fighter-bombers made their bombing runs. I took a couple of photos of the smoke billowing up from the explosions made by the bombs. When the airstrike was over the Company moved to that other mountain top, but found no one there, only some rucksacks with uniforms and gear in them, and some big man-portable pottery jars, all of which were sent back to our re-supply detachment at LZ Buffalo. (The Chaplain came through our detachment at Buffalo, and took the pottery for his personal collection. I confiscated two tiger stripe shirts from the rucksacks, both of which I still have today.)

After a couple of days at LZ Action our little convoy headed back to Buffalo, while the Company remained out in the mountains. The irony of my experience at LZ Buffalo was that on that mission my Company did not make actual contact with the enemy the entire time they were out in the mountains. It was at the supposedly safer support base of Buffalo that the enemy focused their attention. Ultimately in my endeavors to get out of going on that mission in the mountains and keep myself out of danger, I had managed to finagle my way out of the frying pan and right into the fire.

Private First Class Bill Crane

Photo taken on night ambush patrol around Tuy Hòa in early 1971

On April 12, 1971 Private First Class Bill Crane from my platoon came into our area at Buffalo. He had sprained or twisted his ankle while out in the field with the Company, and had been flown to the Medical unit at Buffalo for treatment. They had wrapped up his ankle and sent him on his way. He spent the night with us, and I talked with him for a good while that night. He was trying to decide whether or not his ankle was well enough for him to return to the platoon out in the field. As I was the only one from his platoon with any rank there on the spot, I told him if the doctor had released him, then whether to go back out, or stay at Buffalo and rest for a few days was entirely his decision to make.

Crane was a replacement who joined my platoon fresh from the United States, and straight out of training, in either late December 1970 or early January 1971. He was very young, and several of us speculated that he may have been underage to be in the Army. He volunteered for anything that had to do with going "outside the wire" and into some area where he might potentially see combat. I had been on a lot of night ambush patrols with him in the rice paddies around Tuy Hòa, and Crane was always pestering me to let him walk point on those patrols. I was performing that point duty myself, but eventually I relented and let him take over that duty. He was a real "gung-ho" type, but that night at Buffalo he was having difficulty making up his mind as to whether he should return to the bush or stay at Buffalo for a while.

The next day, April 13, Crane said that he felt well enough and wanted to rejoin the platoon out in the field near LZ Action. That day happened to be a re-supply day for the Company so I drove him to the helipad in our jeep and put him on one of the helicopters going out to the Company. A while later we got word that a Dust-Off (Medical Evacuation) helicopter had brought in a seriously injured man from 3rd Platoon (my platoon) to the Medical unit at Buffalo. I asked the name of the injured soldier and was told it was Crane. Several of us went over to the Medical unit to see about him. They wouldn’t let us in and told us we had to wait outside.

While we waited, we learned the Huey helicopter on which Crane had gone back out to the field had been flown by a new and inexperienced co-pilot. When the co-pilot brought the Huey in to land near the Company, he came in too fast. He over corrected, lost control, and slammed the aircraft into the ground, wrapping it around a tree. The door gunners jumped clear of the helicopter as it went down. The pilots got away with just minor injuries, and were able to exit the ship after impact. Crane, however, had stayed with the aircraft, and was badly hurt and pinned in the wreckage. Ruptured and leaking fuel cells meant the aircraft could explode and burn at any moment. A Lieutenant from one of the other platoons ran to the crash and feverishly worked to get Crane out. I was told that officer literally bent back part of the aluminum skin of that helicopter with his bare hands, and pulled Crane out of the aircraft before it might catch on fire. Though the helicopter eventually did not burn, the Lieutenant was awarded a well-deserved Soldiers Medal for risking his life to save Crane.

I don’t remember how long we waited, but eventually a Dust-Off helicopter landed at the pad next to the Medical unit and kept its rotors spinning. Crane was brought out from the Medical unit on a stretcher, with a medic walking alongside, holding a plasma or other bottle which was hooked up to Crane’s right arm. Crane was carried to the waiting helicopter. He was unconscious and had a pale, deathly color to his skin. His uniform had been removed, and his torso looked like it was wrapped with many bandages, giving the appearance of one huge bandage across his upper body, and most of his left arm and leg was wrapped with bandages. The entire left side of his body, from his shoulder to his foot, including his arm and leg, was somewhat smashed and flattened, as if he was made out of clay or putty. There were bloody spots on his bandages here and there, and a good bit of yellow/orangish color from iodine or something stained his skin around the edges of some of his bandages. He really looked bad, and I didn’t give him much chance to survive. The sight of him left us all feeling sad and depressed, and after we watched him being loaded into the helicopter and flown away, we returned to our tents in silence.

About a week later we were told that Crane was in a hospital in Japan and his condition was stable. His injuries were severe enough to require him to be sent home to the States, so that ended his tour in Vietnam, after only serving there for a few months. I kept wondering if maybe his ankle had been more injured than he let on, and that he wasn’t able to jump free of the crashing helicopter because of that injured ankle. I’ve always felt guilty that I didn’t talk him out of going back into the field, and that I should have convinced him to stay at Buffalo for a few days.

|

The crashed helicopter in

which Bill Crane Somewhere in the

forested/jungle area Note the tree which seems to be

growing The aircraft impacted with

enough force Photo with caption applied by Roger

Pierce |

Above: The entry

showing the helicopter crash incident in which Bill Crane was

injured, taken from the official

Headquarters 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry Historical Summary dated

30 April 1971.

Courtesy of Douglas R. (Grumpy) Banar, E Company 1/22 Infantry 1971-1972

Toward the end of April I received my orders to go home. Mark Marshall and another guy were flown out of the field to Buffalo as they were given orders to go home too. All our dates of departure from Vietnam were close to one another. The three of us strapped on our rucksacks, walked over to the airstrip and hitch-hiked on a plane headed toward Tuy Hòa. Thus it was that I left the re-supply detachment and LZ Buffalo behind. We hopped on an aircraft to Qui Nhon, where we had to wait in the terminal shack for the next available flight from there to Tuy Hòa. We were scruffy and dirty, and were conspicuous with our rucksacks, helmets, rifles, and bandoleers of ammunition, among a sea of unarmed rear echelon types with their clean uniforms and polished boots.

A couple of Army helicopter pilots checked in with the flight desk, saw us sitting on the floor up against a wall, and immediately headed over to us. They too felt out of place, having to wait for their flight among the paper pushers and other rear area soldiers. After introductions and small talk, one of them opened the "day bag" he was carrying and showed me two communist guns he had inside of it, that were sticking out of one end of the bag. With their perforated barrel jackets and folding metal stocks I recognized them right away. They were Soviet or Chinese PPS-43 submachine guns. Where the heck did a helicopter pilot get such things? Probably from guys like us. I handled one of the guns and was impressed by its qualities and characteristics. We enjoyed being with kindred spirits while we waited. When our flight to Tuy Hòa was called, we said goodbye to the pilots, and headed out to the runway to board the aircraft that would bring us one further step toward home.

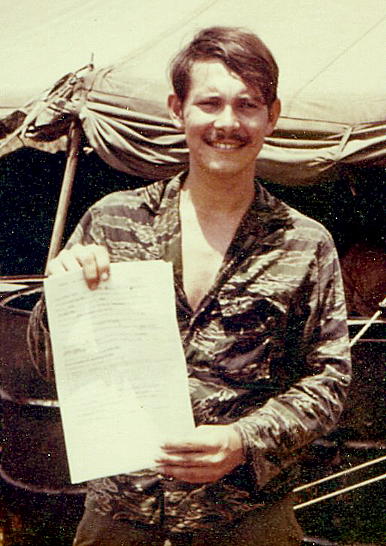

LZ Buffalo April 1971

Me

with my orders to go home. I'm wearing one of the tiger stripe

shirts that came out of a

North Vietnamese Army soldier's rucksack, that my Company had

captured while out in the

mountains around LZ Action in April 1971.

For more

photos of the aftermath of the attack at LZ Buffalo click on the

link below.

Once there click on the Back button to return to this page:

¹ From The Vietnam Veterans Memorial The Wall-USA website

Home | Photos | Battles & History | Current |

Rosters & Reports | Medal of Honor | Killed

in Action |

Personnel Locator | Commanders | Station

List | Campaigns |

Honors | Insignia & Memorabilia | 4-42

Artillery | Taps |

What's New | Editorial | Links |