![]() 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry

1st Battalion 22nd Infantry ![]()

The Jungle

The river

We came down out of the mountains and crossed a wide river once, possibly the Dak May Can River. It was maybe 75-100 yards wide. The water was only about three feet deep at its deepest places, and was clear, not the brown muddy affair the bigger rivers in Vietnam usually were. We crossed it in single file with plenty of distance between each man. Once across the river the platoon stopped and took a break. My squad was directed to re-cross the river and see if anyone was following us. Instead of going back the way we came we were instructed to stay on this side of the river and move parallel along the river for a few hundred meters, then to cross the river and work back along the river to our original crossing point on the other side.

With Sergeant Huey Livingston leading the squad we headed along the river. We moved through the jungle for a couple of hundred meters when the terrain changed from flat to hilly. On our right side the terrain rose parallel with the river and to our front the terrain rose even higher, was perpendicular to the river, and sloped down to the edge of the water. We stopped, because to our left front, on the side of the hill perpendicular to the river, among the trees was a hooch, a hut made of thatch and bamboo. After a few moments the squad moved toward the hooch. Where the hill on our right met the hill to our front resembled the center of an open book, with a depression or shallow crevice in the middle, which we had to step across. In order to do that we had to look down at where we were stepping. The short hill top to our right looked down over this depression and was a perfect place from which an enemy could ambush us.

As each man crossed that depression the man in back of him could cover him by watching that hilltop. However, as I moved forward to the depression I realized that as the last man in line, Charles Lewis behind me had no one to cover him when he stepped across the depression. So after I crossed it I stopped and turned to watch the hilltop while Lewis crossed over the depression. This took a minute. After Lewis crossed I turned around and saw the whole squad was gone. They had disappeared. With Lewis behind me I slowly approached the hooch. In front of the hooch was a small cooking fire going, with a pot of something sitting above it. Obviously our patrol had surprised someone in the act of lunch and they had run away at our approach.

We were still exploring the hooch when we heard noise at the top of the ridgeline above us. Suddenly, with Livingston leading it, the squad came running full speed over the ridgeline and down the side of the hill like bats out of hell. Lewis and I froze, fully aware that if we called out or even moved, it might startle the guys and they might open fire on us. Livingston got almost to me when he slid to a stop, and with his eyes as big as saucers looked right at me, as mad as I had ever seen him be. He muttered “C’mon” and took off running in the direction from which we had originally come. We all followed him and went a couple hundred meters, and then stopped to catch our breath. Livingston proceeded to chew my ass out something fierce. First for not keeping up with the squad and getting separated from it, and then for scaring him by standing near that hooch as he and the squad came running down that hill.

None of my explanations for anything calmed him down and he stayed mad at me for a while. As it turned out, when Livingston and the front of the squad got up to the hooch, they saw the cooking fire and then heard movement on the ridgeline above. They immediately rushed as quickly as they could up the hill. This was at the point where I had turned to cover Lewis, so neither Lewis nor I knew the rest of the squad had gone zipping up that hill. Once on top they looked around and as they moved forward they detected movement in the jungle around them. Believing they had run into more than one or two enemy soldiers, and might possibly be walking into an ambush, Livingston had the squad vacate the area and run down the hill as fast as they could. Coming down that hill so fast, when they saw me and Lewis they were surprised and momentarily scared. We headed back to the platoon, and once we got there we all “rucked up” (gathered all our gear and strapped our rucksacks on) and the platoon proceeded to the hooch, investigated it and the ridgeline above it. We ran into no one; they had all gone. We burned the hooch. We never re-crossed that river to see if anyone was following us.

Not long after the incident at that hut Lewis contracted malaria. One day he didn't look too good during the day, and by that night he was racked with fever and chills. We lay him on his air mattress in our hooch and covered him with our poncho liners and extra ponchos, but he still shook and shivered as if he were freezing cold. At first light the next morning he was taken out of the jungle by a Dust Off helicopter. He was recovered and back with the platoon by sometime in October.

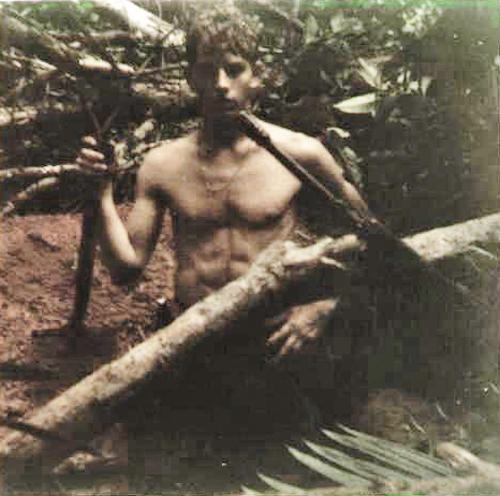

Charles Lewis smoking his

pipe and wearing a flak jacket

as we got ready to convoy to Tuy Hoa 1970

O-2 FAC (Forward Air

Control) aircraft at An Khê in April 1971.

Note rocket pod loaded with phosphorus rockets under the wing.

Buzzed by an O-2

Foxholes were as much a part of an Infantryman’s life as his boots or his rifle. Whenever we stopped for the night we dug foxholes. There was no hard fast rule about the size of the holes but since we normally had three guys to an assigned defensive position we usually made the holes at least wide enough for three men to get in it side by side. We dug them deep enough so that when we crouched or squat in them we would be below ground level. The dirt dug out of the hole was piled up in front of the hole and gave cover if we had to stand in the hole and engage the enemy. Whenever we moved out we then shoveled that dirt back into the hole.

Some guys carried an entrenching tool which was a small Army issued shovel. There were two kinds of entrenching tools. One had a wooden handle and the spade part folded back against the handle. This kind also had a pick part which also folded back against the handle. The other kind was all metal, had a spade part but no pick, and both the spade part and the handle part folded against each other to make a compact bundle for carrying. Each squad had one or more large non-folding shovel which we called a “D-handle”. For some reason at that time the large shovel was something difficult to obtain through the Army supply system and I remember our Company 1st Sergeant took money out of the Company funds, ordered some of those shovels from Sears and had them mailed to the Company in Vietnam. So in addition to our olive drab painted D-handle shovels we had big shovels with bright red handles. I never carried an entrenching tool but I took my turn at carrying the D-handle.

Digging a foxhole was an art that most Infantryman mastered. Wherever we had to dig a hole we hoped the ground would not be too hard or rocky which made digging quite difficult. In the jungle we often hit roots when digging which had to be chopped through. We paid attention when digging, in case we hit a nest of what we called “bamboo beetles”. I remember these as tiny little insects that lived in colonies and their bite felt more like a bee sting than an ant bite. If we uncovered one of their colonies we filled in the hole and started digging another hole a few feet away. It’s possible they were ants, but we called them beetles.

Ralph “Bo” Bonnema was a real king of digging foxholes. He could dig a hole faster and deeper than anyone I ever saw. One time when we had stopped on a ridgeline (hilltop) close to a clearing where the helicopters could bring our re-supply, Bo had dug a foxhole by which I was mighty impressed. I still can remember seeing him in the act of digging that hole using a D-handle and his smile and good natured attitude which we knew him by. Bo had made that particular hole over five feet long by about three feet wide by about three feet deep or so. To my eyes it was a thing of beauty.

That ridgeline we were on was not triple canopy jungle. There were gaps in the trees and we could see big patches of sky through the tree tops. We had been re-supplied and had a sump pit where we were burning our trash and empty c-ration cardboard cases and boxes. Smoke from that fire was wafting up through the trees. As I sat writing a letter, leaned against the back of my rucksack which itself was propped against a tree, I heard the sound of a propeller driven aircraft flying overhead. I looked up and through the gaps in the trees I could see an O-2 FAC (Forward Air Control) type of spotter plane circling our position. None of us paid much attention to him as the whine of his engines seemed to fade.

Then all of a sudden out of nowhere he zoomed above our heads at tree top level. The loud roar made by his aircraft as he flew so low and so close sent guys scurrying for cover. Those O-2’s carried deadly white phosphorous rockets with which to mark targets and a few enterprising pilots even rigged a machine gun to their aircraft so they could shoot at bad guys on the ground. Their job was to direct strikes by attack aircraft against targets on the ground and they could also call in artillery. This pilot had obviously seen the smoke drifting up from our sump fire and was buzzing our location to get a better look at what was down here. We all knew that if he couldn’t identify us as good guys he might well call down devastation upon our position.

Our means of identifying ourselves to aircraft was by igniting colored smoke grenades, an act which we called “popping smoke”. Guys were scrambling for cover and yelling “pop smoke”. I grabbed a smoke grenade off my rucksack, pulled the pin, let the handle fly and tossed the grenade about ten feet away from me. Smoke grenades were being ignited all over our position and their different colored clouds of smoke were all mixing together and flooding the sky above the ridgeline. RTO’s (Radio Operators) were calling on their radios over several frequencies, attempting to alert the pilot that it was Americans on the ridgeline below him.

As soon as I popped my smoke grenade I was up and running, thinking of getting to that wonderful foxhole that Bo had dug. As I approached it I saw there were at least three guys lying in it lengthwise and several others heading for the hole as well, all of whom would get there a split second before me. I abruptly turned away and headed for a small tree. I crouched against the base of the tree, snuggled up against its trunk for protection.

The O-2 buzzed us once more and then circled in the sky high above us before flying off. Perhaps someone on the ground had been able to contact the pilot by radio. If not, he for sure understood it was Americans down here once he saw all that colored smoke coming up through the trees. No North Vietnamese soldiers would be foolish enough to mark their positions with huge clouds of colored smoke for an American aircraft to see.

Later after the excitement had died down I saw Bo and told him when the plane buzzed us I had run to his foxhole, but it already had several guys lying in it face down. He told me “yeah…I know….I was the guy on the bottom and there must have been three or four lying on top of me.”

Ralph “Bo” Bonnema was a seasoned combat veteran who had been with 3rd Platoon since March of 1970. When I got to 3rd Platoon as a “new guy” in September 1970, he was one of the experienced guys who took me under their wing and taught me the skills necessary to operate and survive in the jungle. Bo, Ron “Doc” Sorrento, Ramon Gama, Mike Hernandez, John “Goose” Bryce, Henry “Ski” Jankowski, Henry Shillings, and a few others quickly made me feel part of the group and not an outsider. (Although Shillings also teased me unmercifully about being a “cherry” and an FNG for several weeks at first.)

I joined 3rd Platoon right when Chuck Reed and Joseph Jackson were killed, when they walked into a booby trap. Bo had been friends with both of them, and I remember how he was visibly shaken by their deaths, but he carried on, and had the generosity and compassion to teach a new guy like me things I needed to learn, despite the inner sorrow he must have been feeling. He was a personal inspiration to me at that time. I was lucky to have been in the company of such men.

Ralph “Bo” Bonnema with a D-handle shovel in the jungle 1970

Photo by Ralph Bonnema

The swamp

For one re-supply we came down out of the mountains into a valley. At one end of the valley was a swampy area where we set up our NDP (Night Defensive Position – I remember our term for it was Night Defensive Perimeter). There was an area with trees in between the swampy end of the valley and the open area of the valley. In that open area of the valley was mostly tall grass which made a good landing zone for the Huey helicopters to bring in our re-supply.

While most of the guys were setting up the NDP and getting ready to receive the re-supply, a patrol was sent back up the mountain to see if anyone had followed us. There were five or six of us or so on the patrol. The side of the mountain was covered with jungle but there were some gaps in the trees so we could see some patches of sky through the foliage. We were tired, the going was tough, and we were slow in our progress up that mountain, taking several breaks.

We got about halfway up the mountain side when the Huey helicopters started bringing in the re-supply. We could hear them and could see glimpses of a helicopter now and then through the gaps in the trees. Whoever was our RTO and was monitoring our radio got excited, and said one of the helicopters reported seeing movement (people) on the side of the mountain. We were concerned that there were enemy soldiers somewhere around us that we had not detected, and then we realized the helicopter was talking about us. A Huey zoomed straight at us then banked away from us, turning his broadside to us and exposing us to his door gunner. We scattered and scrambled to hide behind trees, expecting to be hit with machine gun fire from the Huey. They didn’t fire at us and our RTO said the Huey was asking if any of our guys were on the mountain. The reply from our command structure was that a patrol had gone up the mountain but it should be on the top of the mountain by now and not on the side. A frantic call from us let them know we were on the side of the mountain, not the top, and asked them to please not shoot at us. Actually the language used was quite a bit stronger and more colorful than that. We finished our patrol without further incident but for a while there our pucker factor was extremely high.

The terrain feature of the swamp was a good size area in which there were islands of different sizes separated by water. Those islands were solid ground, some with a bit of swamp style vegetation or bushes on them. The islands were close enough to each other so we could step from one to another. Surprisingly we dug foxholes on those islands without striking water. We set up our “hooch” as normal, snapping ponchos together and draping them over branches we had cut into poles, to form a tent. Usually three men to a hooch, with one in the foxhole in front of it on guard duty while the other two slept in the hooch on their air mattresses.

One of the nights we spent in that swamp I was asleep in our hooch when suddenly I got smacked on the head as I lay. Being awakened violently by a blow to the head scared the hell out of me and I screamed. By this time I had acquired the ability most Infantrymen learned, of how to become instantly awake and fully alert at the slightest sound or provocation. This attack on me brought me to my senses in a hurry. In the dark I couldn’t clearly identify my assailant but I saw and heard something scurry away into some nearby bushes. It was something small, not man sized. At this time in my life I didn’t snore when I slept and the other guy in the hooch had been asleep and only awoke when I made my noise, so I knew he hadn’t slapped me to stop me from snoring or something. Putting it all together I had to figure I had been whopped on the head by a monkey. It took a while for me to calm down and go back to sleep.

Next day I was talking to someone about it and Robert Reider was standing near us. When I related how I had yelled when the monkey hit me, Reider said “That was you?” He said he was on guard duty at the time, sitting on the edge of his foxhole which was not far from our position, and when I yelled it scared the crap out of him. He had no idea who screamed or why. Reider said my scream made him literally jump off the ground, and even when he was relieved from his turn on guard duty he stayed awake the rest of the night.

Copyright © Michael Belis 2020

All rights reserved

Home | Photos | Battles & History | Current |

Rosters & Reports | Medal of Honor | Killed

in Action |

Personnel Locator | Commanders | Station

List | Campaigns |

Honors | Insignia & Memorabilia | 4-42

Artillery | Taps |

What's New | Editorial | Links |