![]() 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry

1st Battalion 22nd Infantry ![]()

Night Ambush Patrols Tuy Hoa 1971

We conducted our very first

patrol in the rice paddies in January 1971. Lieutenant Rosine was

in charge of it and the patrol

consisted of the entire platoon. The Lieutenant directed me to

walk point and bring the platoon out into the rice paddies. I was

upset.

I had walked point out in the jungle when we were on search and

destroy back in September-October and since then I had been

promoted to Sergeant. I felt I had done my part doing that

dangerous job and now it was someone else’s turn. Besides, I

was now

a Sergeant and could delegate that job to someone of lesser rank.

The Lieutenant calmly explained

to me that we had not been on an offensive operation since

October and that had been in the jungle

which we had become accustomed to and knew quite well. We were

now in open rice paddies with populated areas around and this

was new to us. We had just received a large batch of

replacements, many of whom were fresh from the States with no

combat experience.

He said that it was a good idea to have someone with experience

out in front to make sure we didn’t walk into an ambush or

booby trap

or even step on a mine. That last part didn’t make me feel

good but even though I was mad I had to admit he was right. Phil

Rosine

was a good officer and a great leader. Everything he said and did

always made good tactical sense and was just plain good common

sense.

I took us out into the paddies

and we immediately came upon some old ruins near which was a

flock of ducks. There was a wisp

of white smoke coming up out of the ruins but we couldn’t

see who or what was in there. I cautiously made my way around the

side

of the ruins while Lieutenant Rosine directed half the column

around the other side. As his column and mine got up to the ruins

I turned the corner and came face to face with an old Vietnamese

man and a young girl of about nine who were cooking over a small

fire.

It was their flock of ducks in the paddy and I was glad I

hesitated instead of shooting.

Lieutenant Rosine was right in

that this was a new experience for us. Out in the jungle anything

that moved was either the enemy

or a wild animal so we had to be fast on the trigger. Here we had

to exercise caution. We got used to this new environment very

quickly

but at first it was quite alien to us. We operated in the platoon

sized patrols for only a short time before someone decided it

made

more sense to spread out into smaller patrols which thereby meant

we could cover a larger area.

The Lieutenant continued to

insist I walk point and my anger quickly subsided as I had to

agree he was right to have me do so.

It even became a matter where I felt safer with me walking point

as I didn’t have to worry if someone else was doing it

right.

That may sound conceited but it was not. It was

self-preservation. I walked point on nearly every patrol I went

on until near

the end when I relented to Private First Class Bill Crane who had

been constantly asking me to let him take the job.

When we settled down into operating the smaller sized patrols we quickly developed a routine.

Once a patrol was dropped off

along the road it made its way into the rice paddies and stopped

near its final location,

determining that location by line of sight but not actually going

to it. The final location was picked to cover a section of a road

or rice paddy dike which the enemy might come walking down. The

patrol waited for darkness then moved out to that final spot.

That way if someone were watching this last movement might

confuse them as to the patrol’s exact location.

A trip wire attached to a trip

flare would be strung across the road or dike in the kill zone.

In the jungle such wires and flares

could be tied directly to a tree or bush but in the rice paddies

no such vegetation usually existed. Therefore a trip flare was

wired

to a stick or tent peg and stuck into the ground with the trip

wire from it running across the road or dike to another stick

or tent peg to secure it.

An M-18 Claymore Anti-personnel

mine would be set up to cover the ambush kill zone. The mine

would normally not be set up

directly on the road or dike but off to the side and aimed in

such a way as to fire down the road or dike at an angle thus

covering

a larger area.

The ambush personnel would also

be arranged to cover a maximum area. Often the patrol could be

laid out behind a dike

running parallel to the dike or road containing the kill zone

which would thus give the patrol at least some

rudimentary cover.

The idea was for the enemy to

come walking into the kill zone where the first enemy soldier

would trip the trip wire setting off

the trip flare thereby illuminating the area and the enemy force.

We would detonate our claymore mine which would be the signal

for the patrol to open fire.

That was the way it was intended

to work. On none of the patrols I was on did the scenario go

exactly like that. Half of the patrols

I was on were completely uneventful and turned out to be a case

of lying in the muck of the rice paddies all night long staring

up

at the stars and thinking of home. The other half contained

events that either directly or indirectly affected the patrol to

make it

a tense night for us. No patrol I was on ended up with the enemy

walking into our ambush and us fighting it out with them though

such a scene did happen to other patrols while I was there.

A normal night ambush patrol

would begin with our platoon gathered together at our barracks at

around 4:00 p.m. for a briefing.

The platoon Sergeant would list the names of men assigned to each

patrol and point out on a map board approximately where

each patrol would go. Any enemy activity in the area as reported

by intelligence or reconnaissance would be given to us at that

time

as well as any special instructions such as being assigned to

work with local militia. We would then draw our weapons and

ammunition

from the Company armory and get ready to go. We loaded up on

trucks and left the base in late afternoon or early evening

heading

down Highway 1 and being dropped off at locations near each

designated ambush site. Each patrol moved out into the

countryside

and set up the ambush.

The ambush required us to lie on

the ground all night. Each patrol would work out a guard schedule

to insure that someone

would be awake at any given time. That person would normally

place himself behind the machine gun with the firing device

for the Claymore mine nearby and handy. He would wake up the next

person for his turn. When we first started these patrols

all of us would be awake all night long but as the nights wore on

and we realized that enemy activity was sparse we determined

it was better to alternate guard watch rather than have everyone

fighting to stay awake and possibly nodding off on those nights

when things were quiet and boring.

Half the time we were all awake

all night long anyway. At the pre-patrol briefing we would

sometimes be informed that

enemy activity was anticipated which would move us to caution and

prevent us from sleeping. Or while on the ambush any

commotion in the area such as gunfire or a firefight would have

us instantly awake and alert for the rest of the night. So too

any noises we heard or movement we detected near us would cause

everyone to remain awake from that point on. I can remember

a couple of times when we detected someone or a few persons

walking near us but not directly into our ambush and all we could

do

was radio their movement and direction back to Headquarters.

As the night ended and dawn

began to break we would dismantle our flares and Claymores, pick

up the machine gun and head back

to the highway to await the trucks which would come to pick us up

at some time after first light.

|

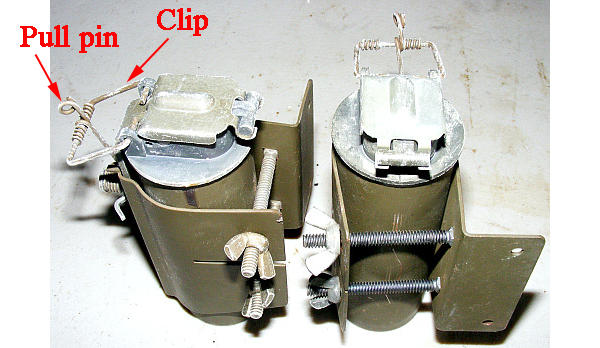

Left: M49A1 Surface Trip Flare The assembly consists of the

flare in its mounting bracket with a pull pin clip A trip wire was attached to the

pull pin and when the wire was tripped The flare was about five inches tall and weighed about one pound. Photo from the Advanced

System Technologies Group website |

The trip flare showing how

it is securely held in the bracket. For the night ambush patrols

this whole assembly was wired to a stick or tent peg

which was then stuck in the ground. It didn’t need to be

hammered into the dirt. It only needed to be secure enough to

allow the pin of the clip

to be pulled by the trip wire. For operational use the flare was

raised to the top of the bracket with the tip of the firing lever

just clearing the trigger.

The clip was removed and the pull pin part was inserted into

either of the holes to secure the lever. The trip wire was

attached to the loop end

of the pull pin. When the pin was pulled by the trip wire the

lever disengaged and the flare ignited.

When ignited the flare burned with a light intensity of 35,000

candlepower for approximately

one minute.

Photo from the Weaponeer.net

website

Red identifications added by Michael Belis

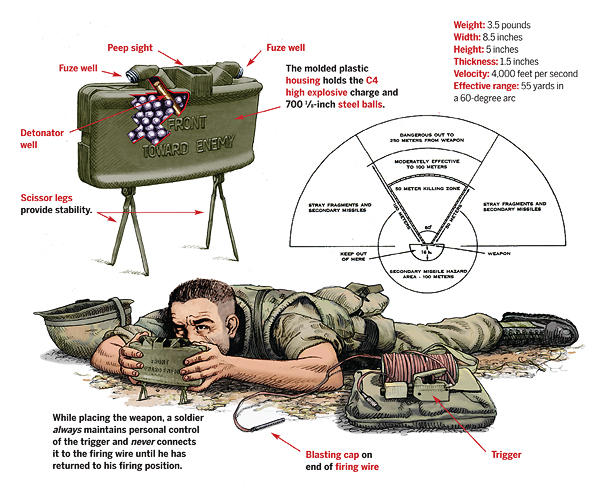

The M-18 Claymore anti-personnel mine

Illustration from the Historynet website

M-18 Claymore

anti-personnel mine – on the left is the firing device or

trigger.

This weapon had a killing zone of about 50 meters in a 60 degree

arc.

Photo from the U.S. Air Force

Patrol from either 1st or 2nd Platoon of Charlie Company about to

move out into the rice paddies on night ambush patrol in the area

around

Tuy Hòa 1971. Second from the left is a machine gunner with his

M-60 machine gun in front of him standing nose down on its bipod.

I don’t know

this machine gunner’s name but I remember talking with him

several times. He was a nice guy and had come to us in either

December or January

from another unit which had gone home. He still had time left on

his tour and was therefore sent to us as a replacement. While

with that other unit

he had been wounded in the shoulder and had an impressive scar to

show for it. On another patrol in this same area (after the one

in this photo)

the truck he was riding in either while going out or coming back

in was attacked by the enemy with an RPG or Rocket Propelled

Grenade

(which in Vietnam we called a B-40 rocket.) He was wounded again,

this time by shrapnel which hit him in his back. Third from the

left the guy

with the fatigue cap is carrying a rucksack on its frame into

which he has stuffed the AN/PRC-25 patrol radio. The whip antenna

of the radio

can be seen sticking out of the rucksack and folded to the left.

On the far right is a Kit Carson Scout. Multi-colored blob in

rice paddy in left center

is actually a flock of ducks which was being tended to by a

couple of civilians. The very first patrol I went on in the rice

paddies went right here

and an old farmer and his granddaughter were in that ruin at the

top of the photo. Smoke from their cooking fire was coming up out

of the ruin.

We had never met them before, didn’t know they were there,

couldn’t see them and until we did they had us worried they

might be enemy soldiers.

After being in the jungle for a long time working in a populated

area was a new experience for us.

We got accustomed to this new environment quickly however.

Photo by Michael Belis

In the morning upon returning to

the base after a patrol we could go to the mess hall to get

breakfast. This base we had taken over

from the Air Force had a stateside type of mess hall and

obviously was still in the supply channels where it could get

real food

like we Infantrymen hardly saw in Vietnam. Often the truck would

bring us straight to the mess hall from the ambush and we would

go down the chow line with loaded weapons and ammo which would

cause unfavorable reaction from some of the rear echelon types.

On more than one occasion some person of lesser authority who

thought he was important would confront us about breaking the

rules

of bringing weapons into the mess hall only to be met with

threatening stares from young Infantrymen who were tired, pissed,

hungry

and dangerously armed. Usually a few words of explanation from

one of us would be enough to send the interloper back to his

table

where he could complain to himself.

One morning after laying in the

mud all night I was in the chow line with my rifle slung from my

shoulder and my bandoleers of magazines

strapped all across me. A cook had a crate of eggs and asked me

how I would like my eggs. Being an Infantryman I had not seen

a real egg in so many months I forgot what they looked like. I

responded “anyway you want to cook them” which I

thought told the guy

how much I was looking forward to eating fresh eggs that were not

dehydrated and powdered. He took this as some kind of affront and

commenced to scream at me something about that he had asked me

simply how I wanted them cooked and why was I giving him such

a hard time and some other diatribe that showed how angry he was.

I was too tired to argue with him but decided that I needed to

show

this rear echelon clown that those of us who laid in the rice

paddies all night long to protect his ass did not appreciate

being messed with.

I unslung my rifle while the cook was screaming something like he

didn’t care if I killed him. One of his buddies quickly

shuffled him

out of the way while another cook asked me if hard cooked eggs

were okay. I slung my rifle back over my shoulder and I said

“sure.”

The cook then explained that this other cook’s father had

died and he was denied leave to go home since the funeral had

already occurred

and that was why he was so upset. The next time I was in the mess

hall and that cook who had been so upset asked me how I wanted my

eggs

I told him over easy. He didn’t seem to remember me and was

just as pleasant as could be. I understood that we were all in

this unhappy

situation together and there was no point in taking it out on one

another.

We could either go to breakfast

first and then back to the barracks or go straight to the Company

area directly from the patrol.

After turning in our weapons and ammo we were free until about

four in the afternoon when we would have our platoon briefing

and told whether that night we would go on patrol or guard duty

or have the night off. So after returning to the barracks in the

morning most of us would hit our bunks and go to sleep for a few

hours. This existence went on from January through March

when the Company was then sent into the interior of the country

for a Search and Clear mission in the mountains around Firebase

LZ Action between An Khê and Pleiku.

At least two patrols I was on

were assigned to work with the local militia, the

“Ruff-Puff’s.” On one patrol we joined about

fifteen

South Vietnamese who were dressed in a mixture of uniforms and

civilian clothes and who were armed with a variety of weaponry

ranging from World War II M-1 rifles and carbines, BAR automatic

rifles to a few M-16 rifles. We all moved to the outskirts of a

small village that was about a mile from the highway and we lay

behind a couple of rice paddy dikes facing toward the west

covering

a road that ran through the paddies connecting this village to

the next. Our patrol was awake all night but we suspected the

South Vietnamese

(who were behind us along a dike positioned to our rear and off

to our side) went to sleep leaving us to do the work of remaining

alert

in the ambush.

On another patrol assigned to

work with the militia we went into a village situated close to

the highway. The head of the local militia unit

got into a heated argument with our platoon sergeant as to what

the duties of the night’s patrol was to be about. Though

there were difficulties

in the language barrier between the two it was apparent that our

leader expected us all to set up the ambush together in the area

outside

the village as he had been directed to do while the militia

leader wanted us Americans to remain in the village while his

people took care

of the ambush outside the village. The confrontation resulted in

a mutual case of distrust and dislike between we Americans and

the

Vietnamese and the situation was tense for a while as both sides

readied themselves should the scene go violent. The situation was

resolved

when our platoon sergeant and I discussed the possibility that

these Vietnamese could be enemy sympathizers or perhaps there

might be

some activity going on that night they did not want us to observe

for some reason. We determined it was best to do things the way

the

Vietnamese wanted. Our patrol remained in the central courtyard

of the village while most of the militia left the area,

presumably to go

set up the ambush outside the village. We spent the night uneasy

huddled on the ground against a building in the courtyard with

most of us

staying awake and two or three of the militia in the courtyard

near us through the night. In the morning the militia leader

appeared and

we bid our goodbyes in a somewhat amicable fashion as we walked

back to the highway to await our truck.

South Vietnamese Regional Force/Popular Force militia dressed in

a mixture of uniforms and civilian clothes. The soldier in the

truck

is armed with a WWII era M-1 carbine. The "Ruff-Puffs"

we worked with looked a lot like these guys.

Photo by Christopher Gaynor from the Daily Mail website

South Vietnamese Regional Force/Popular Force flag

On one patrol we covered a

section of a low levee (only one or two feet high) which ran from

the highway westward toward the

mountains. We set ourselves behind a paddy dike to the north of

the levee and running perpendicular to it facing down the levee

looking west. On the south side of the levee and running parallel

to it was a deep irrigation ditch. On the other side of the ditch

was a dirt pathway wide enough for a cart which also ran parallel

to the levee. At this time of year the sluice gate to the ditch

was closed

so the ditch was empty of water and dry. That ditch was seven or

eight feet deep and around fifteen to twenty feet across. We

stretched

a trip wire attached to a trip flare across the levee, another

across the bottom of the ditch and one more across the cart path.

We set up a Claymore mine to cover the levee, one to cover the

cart path and another Claymore down in the ditch.

Sometime during the night the

trip flare in the ditch ignited. Lying down in the paddy we

couldn’t see into the ditch but the glare

from the flare did give enough light to see down the levee and

the cart path a ways and no one could be seen on either.

We detonated the Claymore in the ditch and waited while the flare

burned itself out. We spent the rest of the night with our

fingers on our triggers but saw and heard nothing else.

As the dawn broke and there was

enough dim light to see, Spanky Sullivan and I crawled on our

bellies across the levee toward

the ditch about 30 or 40 feet apart from each other. As we got

near to the edge of the ditch we looked at each other and I

signaled

with my fingers one, two, three and we both leaned over the edge

with our rifles pointed into the ditch. Lying dead in the bottom

of the ditch was a brown dog about forty pounds in size. Poor guy

had come trotting down that ditch, tripped the wire and set off

the flare. We sent him to doggy heaven when we blew the Claymore.

One of the guys in the patrol said he must have been an

enemy Viet Cong bad guy dog because if he’d been a good guy

dog he would have known not to be out after curfew.

One night another patrol from

our Company about a mile away from the one I was on got into a

fight with the enemy.

We couldn’t see the gunfire but the atmospherics were right

and we could hear some of it across the open paddies.

And we could see some flashes from explosions. It went on

furiously for a while and then stopped. A bit later it began

again

and lasted for another few minutes. A short while after that the

guy monitoring our radio said a helicopter gunship was taking off

from Tuy Hòa to go help.

A few minutes later we watched

the helicopter circle the area of the fight while dropping flares

to illuminate the area. It was a

Huey gunship not a Cobra. A few of us put our ears close to the

radio’s handset and shared listening to the conversation as

the

pilot talked to the patrol on the ground and Headquarters back at

Tuy Hòa. The aircraft made circles and figure eights across the

sky

as it searched for the bad guys. It found them running through

the area heading for the nearby river. We watched as the

helicopter

dived down and saw the red tracers of its machine guns firing

down into the ground.

We heard the pilot say the enemy

was crossing the river as he made a second pass firing all the

way. As he circled above the pilot

related that the enemy had gone into a village on the other side

of the river and requested instructions. It was some time before

Headquarters responded and they told the pilot to fire into the

village. We figured this village was on the list of suspected

enemy

supporters. The pilot continued to circle his aircraft while

repeating several times his request that went something like

“do I read you

correctly that you are ordering me to fire into the

village?” It was obvious he wanted anyone listening to the

radio to know that

Headquarters had ordered him to open fire on the village, that he

had not done so on his own. Once satisfied he had made this

request enough he dived his aircraft and let loose on the village

with machine guns and rockets. He expended his ordnance but

remained on station dropping a flare now and then while looking

for any more evidence of the enemy. After a while he flew back

to Base. All was quiet for the rest of the night and we all

remained awake and alert in case this was part of a larger

operation

by the enemy which might include us.

In the morning we moved back to

the highway and when picked up by our truck were notified we were

not going back to the Base.

The truck brought us south to the same levee where we had killed

the dog on an earlier patrol. Other trucks were parked in the

area

and we moved out along the levee heading west. We found the guys

from our Company down the levee as their patrols had been

brought here as well. We joined them and South Vietnamese

soldiers and militia and stretched out up and down the levee in a

long

formation that covered what looked like a mile or so along it. As

we waited a small party of villagers came down the levee from the

west

with a litter which consisted of a sheet tied to a long pole

being carried by two guys. I walked over to the litter and saw

that inside

the sheet was a person, with blood spotting the sheet. The person

was pretty much covered by the sheet so I couldn’t tell if

it were

man or woman, young or old, soldier or civilian, alive or dead. A

Vietnamese militia officer immediately came over and began

shouting

orders and the two guys carrying the litter and the party of

villagers moved quickly up the levee heading east toward the

highway.

After waiting some more the long line of American and South

Vietnamese soldiers were directed to make a sweep southward

toward the river. A couple hundred soldiers started moving in a

ragged line across the levee, across the irrigation ditch and

through the countryside heading toward the river.

The area where my patrol was

engaged was not rice paddy but rather was open countryside with

sandy soil sparsely dotted with

bushes and areas of mostly waist high tall grass. One of the guys

called me over and I saw that he had found a blood trail going

through the grass. We continued to move through the area

following the blood trail until we got to the river. Upon meeting

the river

the sweep stopped. No bodies or live people had been found though

like my patrol someone else had found a blood trail leading

to the river. After a while we were directed to head back to the

levee, walk back to the trucks and head back to the Base.

The outcome of this episode was left up to someone else.

Sometime later I talked to a

tall black guy who was on that patrol that got into that fight.

He told me the experience was pretty intense

while they shot it out with the enemy. All guys on the patrol

received a medal with a couple of them being slightly wounded.

No Americans were killed that night however.

Our platoon sergeant for 3rd

platoon (my platoon) had led a patrol in the area that night and

I learned that when the shooting started he picked up

his patrol and led them running through the countryside to go to

the aid of the of the patrol that was under attack. He and his

patrol were almost

a mile further away from the beleaguered patrol then my patrol

was. They never made it to the other patrol but stopped and spent

the night

out in the rice paddies.

When I heard that I had mixed

feelings. On one hand it was nice to know he would rush to the

aid of buddies who were in trouble.

But on the other hand I felt it was a bad move to go running

through the countryside at night into an unknown scenario. The

enemy

could have hit that patrol on purpose to draw out reinforcements

who they could then ambush. Or the sergeant could have blindly

stumbled into an American or South Vietnamese ambush patrol in

the dark and get shot up by his own side.

Section of Highway 1 in the area near Tuy Hòa. I believe this is

a bit to the south of our normal patrol range and closer to Phú

Hiêp

and may be the village of Thach Châm which was south of the

Bánh Lái river. Village located near two small South Vietnamese

military

installations (in far left of photo and in upper center just

below shadow of cloud.) Note how many of the houses and buildings

are right

on the highway. Two steps out the front door and you were right

on the asphalt of the road.

Rice paddies on either side of the highway. The mountains can be

seen in the background.

Photo by Michael Belis

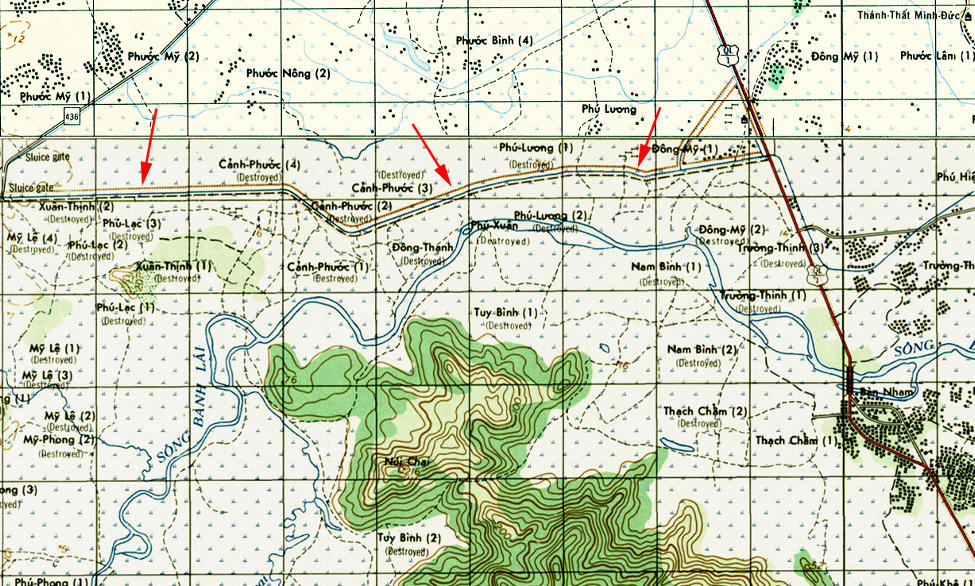

Above: North is to the top. Highway 1 (QL 1) is on the right

marked with the shields. Red arrows point to the brown dotted

line on the map

which is the levee running through the rice paddies from west to

east. Single blue line running parallel to the levee is the

irrigation ditch.

Black dashed line running parallel to that is a cart path. Double

blue line below that to the south is the Bánh Lái river (Sông

Bánh Lái.)

This levee, irrigation

ditch and cart path are where a patrol I was on killed a dog when

he set off one of our trip flares. This is also the place where

after a fight we lined up a couple hundred soldiers or more and

searched for the enemy by moving through the countryside toward

the river.

This location was really

at the southern limit of the range of our night ambush patrols.

Across the river to the south is the tip of a small mountain

range

beginning with the two hundred foot tall hill known as Núi Chai.

Directly to the east of Núi Chai and over on the coast was the

airfield at Phú Hiêp.

This coastal mountain

range extended further south and contained Núi Ðá Bia which

rose to an elevation of over seven hundred feet. The area on the

southern side of the Bánh Lái river came under the

responsibility of the South Koreans who had units stationed at

Phú Hiêp.

The designation

Destroyed under some of the villages does not mean they have been

wiped out. It means that at some time the Vietnamese abandoned

the village or moved it to a different location. For instance

Cành-Phu'òc was moved four times thus it is marked as

Cành-Phu'òc 1, 2, 3 and 4.

Map of Tuy Hòa/ Phú Hiêp area is from two 1:

50,000 maps folded and matched together. Top portion is from grid

map Sheet 6835 II

and bottom portion is an early version of grid map Sheet 6834 I.

Red arrows added by Michael Belis

I was on one patrol with six

other G.I.’s from 3rd Platoon and a Vietnamese Kit Carson

Scout from our 2nd Platoon.

His name was Binh, and though he spoke little English, he was

well liked in our Company. He was typically short in stature

and looked to be in his late twenties or early thirties. He was

serious about working with the Americans and had a good and

trusting

effect on any American he worked with. The Kit Carson Scouts were

former communist soldiers who had surrendered and joined

the South Vietnamese cause. We called them “KC’s.”

As were most of these patrols

this one was uneventful and after laying in the rice paddies all

night long, just before the sun came up

we picked up our machine gun, dismantled our claymore

anti-personnel mine and trip flare and moved out along the rice

paddy dikes.

Our patrol returned to the outskirts of a village along the two

lane blacktop highway in the last moments before dawn to await

pickup

and return back to the base. We moved down the road through the

village until we were nearly all the way to the northern end of

the

village. We stood and waited, half of us on the edge of the road

and half on the ground level porch of a house which itself was

only

about 20 feet from the road when we were fired upon from the

darkness just outside the village. The burst of automatic weapons

fire

smashed into the low roof of the house we were standing in front

of, just missing our heads.

We all hit the dirt and for an

instant no one moved. When we dropped down one guy standing near

me on the edge of the road

scrambled to duck inside the ground level porch of the house and

dropped his rifle. It fell and clattered on the asphalt road

beside me

as I flattened out on my stomach. Our Kit Carson Scout Binh

grabbed the M60 machine gun and began to move in the direction

from which the fire had come. I was immediately up and behind him

and the two of us carefully made our way along the side of the

road

out of the village toward the rice paddies.

I don’t know what went

through Binh’s mind, to make him go after the unseen enemy,

but the reason I joined him was because

I was thinking several things all at once. I figured that if he

had to fire that machine gun the recoil would probably knock his

little frame

backward so I better go with him to put a hand on his back and

hold him up. I also wasn’t happy that one of our new

replacements

had dropped his weapon the moment he was fired upon. My survival

reflex told me not to stay around someone who would do that.

Finally, I didn’t want to stay where I was, in case the

shooter’s next burst might be more accurate and hit us.

With me only a few feet behind

him Binh slowly walked forward slightly bent over with the

machine gun pointed out to his front

and his hand on its trigger. We moved past several houses then

crept along a cement wall which was nearly six feet high and was

the last structure on the edge of the village. I lifted up on my

toes and peered over the wall and saw that it surrounded a

schoolyard.

When I saw the two story plaster sided building that was the

school, for some reason it made me think of the Alamo. The place

where all the defenders died. I suddenly was very aware of how

exposed we were and I thought to myself “what a dumb move

this was…

why didn’t I just stay down on the ground with the rest of

guys?” However, Binh was still going forward, staring

intently into the darkness,

looking for whoever or whatever was out there. Though I no longer

thought this was such a good idea I was compelled to follow this

little guy who was so brave as to take the fight to the bad guys,

rather than just lay there. We continued along the road past the

schoolyard

for another thirty or so meters until we were out of the village

completely and standing in the open with rice paddies to our left

and right.

I instinctively crouched down on one knee and was glad to see

Binh do the same. We scanned the countryside as the darkness

slowly

dissolved into the dim light of the morning dawn.

We took no more fire and after

seeing and detecting nothing we rejoined the rest of the patrol.

Apparently our assailant fired his one try

and took off. It might not have even been the enemy, it could

have been some local with a grudge against Americans. Binh gave

the

machine gun back to its owner and quietly kept to himself. I was

moved to admiration and respect for this former enemy. While the

rest

of us froze, it was our Kit Carson Scout who had reacted quickly

and strongly.

Not all the Kit Carson Scouts

were like Binh. Some didn’t hold our trust and some were

just not good soldiers. We had a couple of them

in 3rd Platoon who we had problems with and who we eventually

refused to work with because they were just about useless to us.

(Myself and Jim Regalia were detailed to return the two of them

back to the Chiêu Hôi center in Saigon on Christmas Eve 1970.)

Most of our night ambush patrols

did not include a Kit Carson Scout. Our Kit Carson Scouts were

assigned to the different Platoons

in our Company and went out on the patrols with us just as any

other member of the Platoon would. But that night, standing along

Highway 1 on the coast of the South China Sea, I felt lucky the

patrol I had been on had a Kit Carson Scout named Binh.

|

Left: Kit Carson Scout Binh

mentioned above. I took this photo See full photo below. Photo by Michael Belis |

Members of Company C

stopped along Highway 1 on deployment of night ambush patrols

around Tuy Hòa 1971. In the foreground

huddled together reading the map with their backs to the camera

are Specialist 4th Class Mike Hernandez (without a hat and with a

big knife

stuck in the pocket of his trouser leg) and Staff Sergeant

Williams (with the boonie hat.) Kneeling on the ground to the

right of Williams is Utah

our truck driver. At the top far right facing the camera with a

wide brim boonie hat and cradling his rifle is Kit Carson Scout

Binh from 2nd Platoon.

At the end of one

uneventful patrol that I was on with Binh and six other guys, as

we stood along the road just inside the edge of a village

awaiting

pickup just before dawn we took a burst of automatic weapons fire

from the rice paddies just outside the village. The bullets

smashed into the low roof

of a house we were standing in front of just missing our heads.

Binh grabbed our machine gun and I followed behind him as we made

our way

along the road out of the village toward the paddies.

Once we got beyond the

end of the village we stopped and scanned the darkness of the

countryside but we saw and heard nothing and took

no more fire. No one was hurt but it gave us all a good scare.

Photo by Michael Belis

Soldiers from 3rd Platoon Company C 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry

move out into the rice paddies near Tuy Hòa on night ambush

patrol,

early 1971. The machine gunner is in the middle holding his gun

pointed up. Second from the right is Private First Class Bill

Crane. On the far left

is Sylvester Bobo. Bobo carried both an M-16 rifle and an M-79

grenade launcher on these patrols. His grenade launcher can be

seen

slung across his back and his rifle can be seen lazily draped

over his left shoulder. This is not a complete patrol as the

radio man is not in the photo.

He is probably to the left out of the frame. This is the kind of

open rice paddy area as described in the incident related in the

sections below.

Photo by Michael Belis

One night instead of being on

night ambush patrol I was sergeant of the guard for our platoon

as it was on guard duty at the Base

at Tuy Hòa. That night the enemy attacked a South Vietnamese

Army (ARVN) garrison near our Base. From a guard tower on the

north side of our Base I had a front row seat to watch the attack

and even took a couple of photos of the attack in progress.

The next time I went out on night ambush patrol our truck passed

right by that ARVN compound and we were able to view

the results of the attack as we drove by. At least three of the

buildings were burned to the ground. Another building with a

stucco

type exterior had a huge hole in the end of it with the edges of

that hole blackened by smoke. There was a lot of other damage and

debris all over the ARVN compound that showed that the attack had

been pretty intense for whoever was in the garrison at the time.

It was a grim reminder that even though most of our patrols were

uneventful the enemy was still in the area and able to carry out

operations. We always understood that any of the patrols could

turn deadly at any time.

When we first started going out

on these patrols I made sure I carried a Claymore mine with its

firing device and a spool of electrical

wire for it. I also carried a trip flare that I had wired to a

stick while we were out in the jungle back in September-October

and had kept

even after we had been pulled out of the jungle. As time went on

I stopped carrying the Claymore as I found other guys who were

more

than willing to do so but I still carried the trip flare attached

to the stick and another stick to tie the end of the trip wire

to. This assembly

was a work of art and I had constructed it so well it was still

working after many months of usage. Other guys began to imitate

what

I had done with the trip flare and eventually I found I could

stop carrying the flare as well. It made for less of a load I had

to carry

and less duties for me by not having to set it up and take it

down.

Near the end of March I was on a

patrol consisting of either six or seven men altogether. I

don’t remember the number exactly

or the names of who was on the patrol. I was not in charge of the

patrol, there was another sergeant who was one grade above me

in rank. We went way out into the rice paddies and picked a spot

where we could lie behind a small paddy dike and cover another

larger dike running parallel. There weren’t any houses

around in any direction for nearly a mile. We were in open rice

paddies.

As we prepared to set up the

ambush we found that no one had brought a trip flare. I got mad

about that but not at anyone but myself.

I had stopped bringing along my own trip flare out of laziness or

selfishness. But I had also not checked the patrol before we left

the Base to make sure that someone had a flare or even checked to

make sure someone brought a Claymore or any parachute flares.

Someone had brought a Claymore thank goodness but no trip flare

and no parachute flares!

The men assigned to each patrol

were hardly ever the same so it wasn’t a case of the same

guy always carried the Claymore or

the same guy always carried the flare and the flare guy forgot it

this time. It just turned out that no one brought any flares that

night.

Since I was not the leader of this patrol it was technically not

my responsibility to make sure the patrol had everything it

needed.

But as a sergeant I should have taken that load off the patrol

leader and checked to insure the patrol I was on had all it

should.

I usually did exactly that and I was now kicking myself for not

doing it that night. I screwed up.

Without that flare to warn us of

the enemy’s approach we decided that all of us would have to

remain awake throughout the patrol,

just in case. To the credit of the men that night everyone agreed

without a single bit of grumbling. We did not have a night vision

device

with us but the moon was half full and the clouds were reasonably

thin so we had some semblance of visibility.

A little past one in the morning

we heard voices approaching us from the left. Since we were

facing west that meant someone was

coming up from the south. They weren’t talking loudly but

they weren’t whispering either. And it appeared they were

walking along

the dike we were covering and were coming right into our kill

zone.

We all quickly and quietly

checked each other to make sure everyone was awake and alert to

the danger. I was lying to the right

of the machine gunner with the patrol leader a couple of guys

down on the gunner’s left. The machine gunner brought his

gun up

to his shoulder with his finger on the trigger.

I picked up the firing device to

the Claymore mine and made sure the safety clip was in the down

or firing position. Since I held

the firing device it would be my responsibility to initiate the

ambush by detonating the mine. That would be the signal for the

machine gunner and the rest of the guys to open fire.

The voices were coming closer

and we could tell they were speaking in Vietnamese not English.

They were speaking in hushed tones

but still carried loud enough so we could hear them. Something

made me lean over and place my mouth touching the ear of the

machine gunner and I whispered “hold your fire.”

The intruders began to cross

through our kill zone. There was just enough night vision to see

them as dark silhouettes as they passed

before us on the dike opposite us one hundred feet away. The

field of view of our vision in the darkness was limited to about

twenty

feet wide. We could not distinguish uniforms but it was evident

they were carrying weapons though we couldn’t tell what

kind.

About five had walked by when I

began to count them. Only the first couple of them had been the

ones doing the talking.

I stopped counting at twenty-five. At least ten more walked by

after I had stopped counting. That meant there had been forty

or more of them altogether.

I had not blown the Claymore and

the other guys had not opened fire, obviously waiting for the

signal and not shooting since

they had not received that signal to do so. I was incredibly

thankful and proud of the fire discipline of the men I was with

that night. If we had opened fire we would have killed some of

the enemy but not most of them. Strung out as they were

along that dike I don’t think we would have got very many of

them at all. That would have left most of them to return fire at

us.

And with no flares to light them

up for us we would have been firing blindly into the dark at

them. They, on the other hand,

would have known right where we were by the light of our muzzle

flashes and they could have concentrated all their guns on us.

Their initial response could have been devastating to us.

I don’t know what made me

hold our fire that night. Call it a sixth sense, call it fate,

call it God. I certainly can’t explain it.

It was just a feeling I had and as it turned out I was glad I had

it. The enemy had not seen our Claymore because it was off the

dike

and in the paddy and they had not seen us because we were lying

down behind the opposite dike a hundred feet away in the

darkness.

We waited a couple of minutes

until we were sure there were no more coming and then the patrol

leader got on the radio

and called Headquarters and informed them that forty Victor

Charlies (phonetic pronunciation for the letters VC for Viet

Cong)

just passed by our location heading north. By giving our

patrol’s call sign Headquarters would know our location. The

rest of the night

was uneventful but tense as we remained alert until daylight when

we could head back to the Base.

A couple of days later one of

our Lieutenants came up to me as I stood behind our platoon

barracks. He had heard about

the incident of the forty enemy soldiers walking through our

ambush. I think he may have been Lieutenant Trent but can’t

remember

for sure. I do however remember the conversation. In response to

his question of what it was like I related to him the events of

that night.

I told him it was probably a group of ARVN (friendly South

Vietnamese soldiers) and we had been scared for nothing. He told

me

“Sarge I was at the Battalion briefing before the patrols

that night and the Captain specifically asked if there would be

any ARVN patrols,

ambushes or movements in our area of responsibility that night

and the briefer responded that no ARVN activity was scheduled for

that night.”

If I had done my job correctly

that night and made sure we had brought a trip flare and we had

set up that flare like we should have

across that dike the enemy would have walked right into it,

setting it off. We would have had no choice but to initiate the

ambush and

open fire.

Is it possible we could have won

that fight? Maybe. But as outnumbered as we were out in that open

field it’s more likely

we would have got ourselves shot to hell instead.

All the time I had been in this

war I had been working so hard to screw up as little as possible

and yet that night it was a screw up

that quite likely saved our lives. What insanity.

Since I spent nearly all of

April 1971 (my last month in Vietnam) at LZ Buffalo the night

ambush patrols were over for me

by the end of March. My part in them had lasted from January

through March 1971.

I left Vietnam for the United States the first week of May 1971.

Home | Photos | Battles & History | Current |

Rosters & Reports | Medal of Honor | Killed

in Action |

Personnel Locator | Commanders | Station

List | Campaigns |

Honors | Insignia & Memorabilia | 4-42

Artillery | Taps |

What's New | Editorial | Links |