![]() 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry

1st Battalion 22nd Infantry ![]()

MEDAL OF HONOR

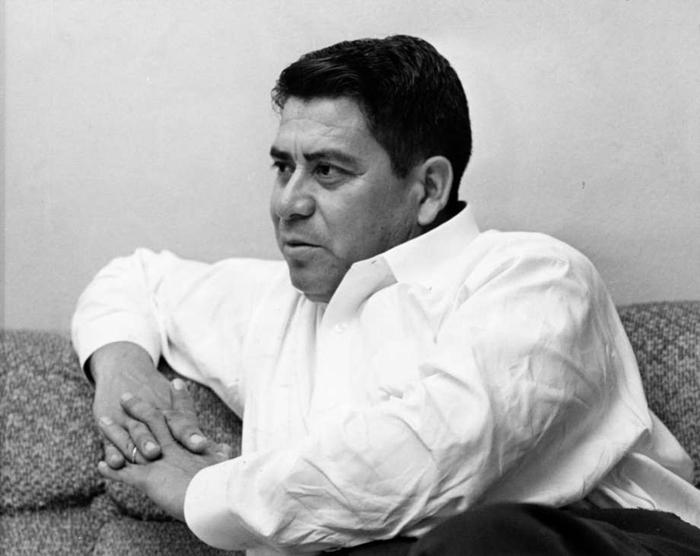

Macario Garcia

Company B 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry

Macario Garcia looks over his Medal of Honor November 1960

Photo from the Houston Chronicle

Medal of Honor recipient wasn't

always celebrated

Once he returned to Fort Bend County,

Mexican citizen endured mistreatment

Mike Glenn | August 8, 2016

On Aug. 23, 1945, a man from Missouri who commanded an artillery

battery in World War I draped a decoration

around the neck of a young infantry soldier from Sugar Land.

"I would rather have a Medal of Honor than be President of

the United States," President Harry S. Truman told then

Staff. Sgt.

Macario Garcia along with other military members at the White

House that day to receive the nation's highest award for combat

valor.

Born in Mexico, Garcia was working as a farmhand in November 1942

when he was drafted into the Army. He was 22,

and within about three years, Garcia would battle his way across

Europe and, later, fight for his own dignity back home in Texas.

The wartime battle that secured a place in the history books for

Garcia was waged on November 27, 1944, while he was an

acting squad leader with B Company, 1st Battalion, 22nd Infantry

Regiment - part of the 4th Infantry Division.

Like many other allied units in the European Theater at that

time, Garcia's 4th Division - nicknamed the Ivy Division - was

struggling

through Germany's impossibly dense Hurtgen Forest and fighting in

a series of vicious clashes that lasted from September 1944

until February 1945. The Germans and the Allies each suffered

about 30,000 casualties during the action.

TIMELINE

Jan. 20, 1920 Born in Villa de Castano, Mexico.

Nov. 11, 1942 Inducted into the U.S. Army.

Nov. 27, 1944 Fought in a battle in Germany that led to the Medal

of Honor.

Aug. 23, 1945 President Harry S. Truman presents him with the

Medal of Honor at the White House.

June 25, 1947 Becomes U.S. citizen.

Nov. 21, 1963 Official greeter for John F. Kennedy during his

Houston visit the day before the president's assassination in

Dallas.

Dec. 24, 1972 Dies from injuries after a car accident.

Macario Garcia and his family September 21, 1968

Photo from the Houston Chronicle

Garcia's unit was pinned down by an overwhelming mortar barrage

and machine-gun fire on the outskirts of Grosshau, Germany.

According to his Medal of Honor citation, Garcia - then only a

private - was himself wounded but refused to be evacuated.

There was no easy way to get to the entrenched German position

now raking his fellow soldiers with fire. Inch by inch, the

still-bleeding Garcia crawled forward until he got close enough

to hurl a grenade into the machine-gun emplacements. Then,

he killed three of the German soldiers who attempted to escape.

But his fight that day wasn't over

Another enemy machine gun opened up when Garcia returned to B

Company. Again, he raced forward and destroyed the

emplacement, killing three more German soldiers and capturing

four others. Garcia continued fighting on with his fellow

soldiers

in B Company until their objective was taken.

"Only then did he permit himself to be removed for medical

care," his Medal of Honor citation states.

In an interview with the Houston Chronicle several years later,

Garcia said: "I did not know the wound was so serious.

I was numb, I think, and besides, we were moving forward, and it

was not the time to stop."

Capt. Tony Bizzarro, the B company commander, made the initial

recommendation for the Medal of Honor.

He thought Garcia was nothing less than the best soldier in the

Army.

"He was always willing to do anything he was asked to

do," Bizzarro later told the Chronicle.

About nine months later, the young farmhand turned soldier - at

that point still a Mexican citizen - was standing before Truman.

Macario Garcia in 1943 was away fighting the Nazis when his

brother, Lupe, was born. "He was 23 years older than

me,"

Lupe Garcia, who lives in the Houston area, said in a recent

interview.

For a few years, the significance of what Macario Garcia had

accomplished on that bloody battlefield in Germany

was lost on his younger brother.

"I didn't know what (the Medal of Honor) was," Lupe

Garcia said. He doesn't remember his older brother talking about

the war after he returned home to Texas. "He would probably

talk to some GI, but if he noticed I was listening,

he would quiet down," Lupe Garcia said.

Macario Garcia became something of a local celebrity when he

returned to Sugar Land. He once brought his younger brother

to a baseball game in the neighborhood where strangers would ask

to shake his hand.

"Next thing you know, somebody sent over a round of

drinks," Lupe Garcia recalled. "People would want to

have him

as the best man at their wedding."

The surrender of the Nazis in Europe did not signal the end of

his struggles. On Sept. 10, 1945, Garcia stopped in for a meal

at the Oasis Cafe in Richmond. At that time, shortly after the

White House ceremony, he was the toast of the town.

Newspaper reporters wrote glowing articles about his combat

heroism, and a party was thrown in his honor at Richmond's city

hall.

But his reception at the Oasis was less welcoming. Although in

full uniform, including a chest covered in combat decorations,

Macario Garcia was refused service because of his Mexican

ancestry.

"I've been fighting for people like you, and now you

mistreat me," he reportedly told the proprietor.

A fight broke out after Anglo sailors at the cafe sprang to his

defense. Garcia was the only one arrested.

The case against Garcia quickly became something of a cause

célèbre after Walter Winchell, the famous newspaper columnist

and radio host, criticized local authorities for their treatment

of the returning hero.

Charges against Garcia eventually were dropped.

Michael Olivas, the interim president of the University of

Houston-Downtown and a University of Houston law professor,

has written about the Garcia case. What happened to the war hero

at the cafe, Olivas said, wasn't particularly unusual in Texas.

"This was sort of standard practice," he said.

"The Texas Restaurant Association printed up signs that

appeared in most white

restaurants that said, 'No Mexicans or dogs.' It would say it in

English and Spanish."

He said Winchell's interest proved so embarrassing for Fort Bend

County officials that they simply let the charge against Garcia

die.

Macario Garcia November 1960

Photo from the Houston Chronicle

In June 1947, Garcia became a U.S. citizen.

"The only thing he didn't have was an education," Lupe

Garcia said.

After returning home, he resumed classes and eventually graduated

from what was then known as Sam Houston High School

in downtown Houston.

He met his future wife, Alicia Reyes, at a dance after the war.

The couple married and had three children, Carlos, Maria and

Rene.

For 25 years, he worked as a counselor in the Veterans

Administration. He continued in the Army reserves after the war,

eventually achieving the rank of command sergeant major.

On Nov. 21, 1963, Garcia greeted John F. Kennedy at the door of

the Rice Hotel during the president's visit to Houston.

The next day, Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas.

On Christmas Eve in 1972, nine days before his 53rd birthday,

Macario Garcia was killed in an automobile crash.

His wife died in February this year.

His portrait now hangs in the Fort Bend County Courthouse in

Richmond.

In addition, Garcia Elementary School in Houston and the Fort

Bend Independent School District's Garcia Middle School

both were named in his honor. City officials renamed a 1.5-mile

stretch of 69th Street "Staff Sgt. Macario Garcia

Drive."

It runs through the heart of the city's east side

Mexican-American community.

In 1983, then Vice President George H.W. Bush dedicated the

Macario Garcia Army Reserve Center

in honor of the soldier from Sugar Land.

Mike Glenn|Reporter, Houston Chronicle

Home | Photos | Battles & History | Current |

Rosters & Reports | Medal of Honor | Killed in Action |

Personnel Locator | Commanders | Station List | Campaigns |

Honors | Insignia & Memorabilia | 4-42 Artillery | Taps |

What's New | Editorial | Links |