Edmund Francis Thornell

21st Tactical Air Support Squadron

505th Tactical Control Group 7th Air Force

Attached to HHC 1/22 Infantry

KIA 09/10/1966

PERSONAL DATA:

Home of Record: Redondo Beach, CA

Date of birth: 09/10/1933

MILITARY DATA:

Service Branch: United States Air Force

Grade at loss: O3

Rank: Captain

Promotion Note: None

ID No: 53783

MOS or Specialty: -----: Not Recorded

Length Service: 14

Unit: 21ST TAC AIR SPT SQDN, 505TH TAC AIR CTRL GROUP, 7TH AF

CASUALTY DATA:

Start Tour: Not Recorded

Incident Date: 09/10/1966

Casualty Date: 09/10/1966

Age at Loss: 33

Location: Phu Yen Province, South Vietnam

Remains: Body recovered

Casualty Type: Hostile, died outright

Casualty Reason: Fixed Wing - Crew

Casualty Detail: Air loss or crash over land

Captain Edmund F. Thornell was

piloting a Cessna O-1E Bird Dog aircraft number 56-4184

while on a Forward Air Controller reconnaissance mission for 1st

Battalion 22nd Infantry

when his aircraft was struck by enemy ground fire from a .50 or

.51 caliber heavy machine gun.

His aircraft crashed inland, at grid coordinates CQ 300302,

approximately 250 yards from the sea,

about ten miles south of Tuy Hoa Air Base in Phu Yen Province.

He was killed in action on his 33rd birthday on September 10, 1966.

Pocket patch of the 21st Tactical Air Support Squadron

Edmund F. Thornell was born in Stoughton, Norfolk County, Massachusetts on September 10, 1933.

He entered military service on June 29, 1951.

Captain Edmund F. Thornell

shipped out to Vietnam in July 1966 on board the US Naval Ship

General Nelson M. Walker

which carried the 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry and the 1st

Battalion 12th Infantry. The USNS Walker arrived at Qui Nhon,

Vietnam on August 6, 1966. Captain Thornell was killed in action

only a little more than one month later.

At the time of his death he was married and had two sons and two daughters.

He was carried in the records of

1st Battalion 22nd Infantry as being a member of Headquarters

Company 1/22 Infantry

at the time of his death.

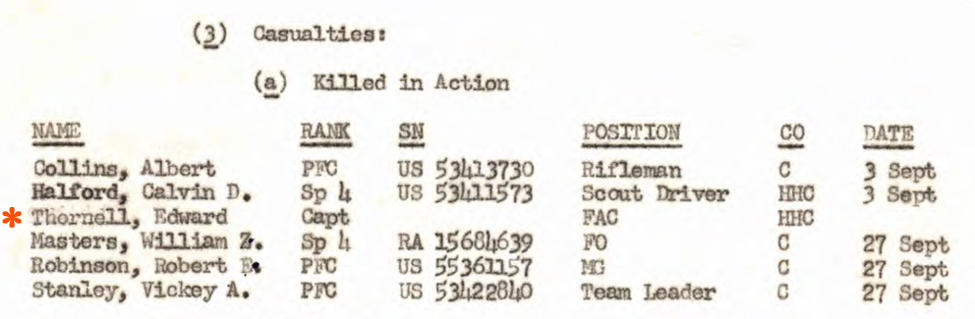

Above: Part of the

casualty report for 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry for the month of

September 1966.

Captain Edmund Thornell's name is marked with a red asterisk. His

first name is incorrectly given as Edward.

The entry shows him listed as being assigned to Headquarters

Company 1/22 Infantry when he was killed in action.

His job descrption is given as FAC (Forward Air Controller.) His

serial number and date of death are not given in the report.

Courtesy of Herb Artola

Decorations of Captain Edmund F. Thornell

![]()

The name of Edmund F. Thornell on the

Vietnam Wall in Washington, D.C.

His name is inscribed on Panel 10E Line 065.

Robert "Bob" Babcock

was a Lieutenant and Platoon Leader of 3rd Platoon B Company 1/22

Infantry

in 1966. Bob remembers talking with Captain Thornell on board the

USNS Walker as they both sailed

to Vietnam in July/August 1966. When Captain Thornell was shot

down Lieutenant Babcock was tasked

with the mission of recovering Captain Thornell's body. Bob

Babcock describes the mission which he led

on September 11, 1966:

"It was after 1:00 AM as I

got my briefing from Major High on our morning’s mission. I

was still keyed up

from our harrowing experience of providing relief to our bridge

outpost.

“Yesterday afternoon, between 4:00 and 5:30, one of our

battalion forward air controllers was flying

a reconnaissance mission when his plane went down. The wreckage

was found just before dark.”

“A man was lowered down to it and found the pilot, dead in

the cockpit, and the plane still burning.

We do not know what caused the plane to go down, but we suspect

it was shot down by a .50 caliber machine gun.”

“Your mission is to be there at daylight and bring out the

body. We have only three helicopters available so you

are limited to 24 men, including yourself…,” Major High

continued giving me the details on the terrain and

other items I would need to know to accomplish the mission.

Needless to say, I did not look forward to this next challenge. I

was drained from the mission we had just completed,

I did not like the prospect of running into a .50 caliber machine

gun, and, most of all, I did not look forward to

pulling a burned dead man out of an airplane. My mind could

picture the grotesque sight that would greet me

when I got to the airplane. As usual, I did not get to vote, so

the mission was mine to accomplish.

It was an easy job for me to select the three squads that would

go, Sergeant Benge and his third squad,

Sergeant Burruel and the two machine gun sections from his

weapons squad, and Specialist Muller and his

second squad. Sergeant Roath, Stanley Cameron, my radio operator,

and I would take up three of the slots.

I sent a runner to the perimeter to bring back Muller to join

those of us who were not on perimeter duty.

It turned out the night off for Sergeants Roath, Benge, and

Burruel had been anything but relaxing. At least they

were all sober after the mission to the bridge outpost.

Major High had instructed me to bring my men off the perimeter at

4:30 AM and be ready to get on the helicopters

by 5:30. After briefing my squad leaders, I decided I would try

to get a little sleep. With two hours before we

had to start getting ready, I was convinced some sleep would do

me a world of good.

As soon as I closed my eyes, I could see an image of the pilot in

the burned out cockpit. I tossed and turned

and tried to think of something else but my mind always came back

to what lay ahead of me. After half an

hour, I gave up on sleep, got up, and cleaned my rifle to occupy

my time and my mind. I had never had a job to do

that I dreaded so much. Maybe it was because I knew the pilot (we

had talked frequently during the boat trip to

Vietnam) or maybe my mind was just painting too vivid a horror

picture.

It was still dark as we loaded onto the helicopters. Our

destination was ten miles straight south. The plan

was to land on the beach and work our way inland. Not knowing

where the .50 caliber machine gun was, the helicopters

would not fly over the crash site to let us see what we were

going after. We had to rely on our map, compass, and

high level observation from a helicopter on station above us

after we were safely on the ground.

Just before the helicopters took off, one of the battalion

intelligence sergeants ran up to my chopper and handed me

a Polaroid camera. “Take pictures of the plane and the path

it cut as it crashed. We want to try to determine

what caused the crash and which direction it was coming from as

it crashed.” I really was not thinking of myself as a

photographer that day, I was thinking only of getting in there,

getting the pilot, and getting the hell out.

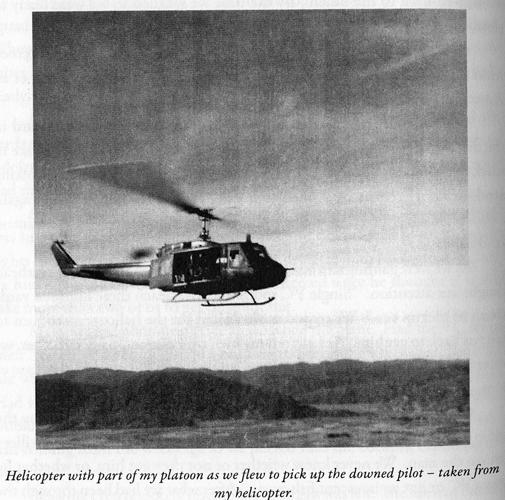

One of the helicopters on the mission to recover the body of Captain Edmund F. Thornell

Photo from WHAT NOW

LIEUTENANT? An Infantryman in Vietnam by Robert O. Babcock,

Deeds Publishing

Company Marietta, GA 2008

We flew at low level over the South China Sea. The pilots

ascended briefly to get their bearings before

they hovered in for a landing on the beach, just a few yards from

where the waves were hitting the sand. It took us

no time to leap from the helicopters and disappear into the

brush, a forty yard sprint away. It was just getting daylight

as we cautiously started working our way inland. The terrain was

rolling sand dunes covered with thick thorn bushes.

One machine gun team set up on the top of a dune to cover the

point squad as they hacked a path through the bushes

that tore at our fatigues. When the point got out of sight of the

covering machine gun, we set up the

other machine gun team on a sand dune and leap-frogged the first

team to be ready to take over again.

After about an hour of slow but steady movement, we had covered

500 yards and could see the crash site.

As we had planned, the three squads formed a defensive perimeter

around the site. Sergeant Roath, Sergeant Benge,

and I had the job of pulling the body out of the plane.

As we had discussed the mission a few hours earlier, Sergeant

Roath was insistent he should do the dirty work

since he had seen so many similar sights during the Korean War. I

could not disagree with his logic and gladly

let him come along. Sergeant Benge volunteered since he thought

it would

take more than two of us to get the pilot out.

My heart was pounding as we approached the plane. Had the VC set

up their .50 caliber machine gun in a position

to fire on the wreckage? The crash site was well within range of

a machine gun set up in the surrounding hills.

Had they been in during the night and booby trapped the airplane?

What would we find in the cockpit of the plane?

A few small wisps of smoke were still coming from the wreckage as

we peered into the cockpit, expecting the worst.

Nothing even remotely resembling a human was left. The fire had

burned intensely and nothing was left

of the pilot’s body but the trunk. The only recognizable

things on the body were his dog tags and a Saint

Christopher’s medal. The thought that crossed my mind was,

“It’s a damned dirty shame anyone had

to die like that.” I just hoped he had been killed by

gunfire and had not burned to death.

Once we knew what we had to deal with, we quickly went to work so

we could get out of there.

As instructed, I took a roll of Polaroid pictures. The close-up

pictures of the bullet holes in the tail of the plane

left no doubt it had been shot down by a .50 caliber machine gun.

We removed the body, zipped it into a body bag, and moved away

from the wreckage. We knew now

there was a .50 caliber machine gun around there somewhere and we

did not want it to find us. Using

the same caution, we moved back to the beach. By the time we

reached it, we were ready to

slump down for a rest.

As I lay on the sand, listening to the waves pound the beach, it

seemed more like a serene vacation spot

than a place that had claimed the life of an American pilot only

a few hours before.

Our rest was short as the sound of the helicopters could be heard

in the distance as they came to extract us.

They radioed for us to pop smoke to mark our location. After

identifying our red smoke, they hovered in,

kicking sand into our faces as we rushed to board. Soon the

choppers were again airborne,

leaving the crash site behind, another grim scar on the

Vietnamese landscape.

As we were gaining altitude, a

radio call from a gunship circling overhead caught our attention.

“Single VC spotted on the beach three hundred yards south of

pickup site.” We tensed as we

waited for the helicopters to turn to take us back to get him. As

I alerted my men over our company

radio net, we were told we were heading back to base camp, the

artillery would take care of him.

Charlie Battery, 4-42 Artillery

responded quickly. As we listened on the radio and watched from

our choppers, they dropped fifty rounds of artillery fire on the

man. We never knew whether or

not they got him.

By 9:00, we were back on the

ground at our base camp. An aid truck met us and took the

pilot’s

body to graves registration. Sergeant Angulo had saved hot

breakfast for us, and the intelligence

section wanted to ask me a thousand questions about what we had

seen and to explain everything

in the Polaroid pictures. Guess who won?

The intelligence people had to

wait on the questions. I was hungry and anxious to hear Sergeant

Angulo and the other rear echelon guys tell their tales about

their mission to the bridge outpost

the previous night. " ¹

Lieutenant Bob Babcock who led the mission to recover the body of Captain Edmund F. Thornell

Photo from WHAT NOW

LIEUTENANT? An Infantryman in Vietnam by Robert O. Babcock,

Deeds Publishing

Company Marietta, GA 2008

Bob Babcock further wrote:

I was platoon leader of B/1-22

IN who flew to the beach near where Captain Thornell's plane

crashed. We

worked our way to the still smoking wreckage, knowing an enemy

.50 caliber machine gun was in the area. While

our platoon provided security, my platoon sergeant and I removed

his body from the wreckage. We treated the

remains with the respect all American casualties deserve. I never

knew his name until just recently, but will

never forget that mission that was given to me as a rifle platoon

leader.

Bob Babcock and Bill Stevenson

have collaborated on a project to indentify the location of the

crash of Captain Edmund F. Thornell's aircraft. Thanks to the

diligence and persistence of Bill,

the exact grid coordinates of the crash site were discovered.

Bill has prepared a document

containing maps and information about the crash and recovery of

Captain Thornell.

The document can be viewed at the link below. The link is to a

PDF file.

To return to this page, click on the back button in the file.

Click on this link:

The Army, Air Force and Marine FACs in the Vietnam War played an essential role in locating enemy units, coordinating air-ground combat operations, and most critically, managing close air support. The "low and slow" nature of their missions -- typically flown over heavily forested terrain concealing enemy anti-aircraft weaponry -- necessarily involved extraordinary danger, as a result of which their specialty had among the highest casualty rates of the War. To an even greater extent than most who served in Vietnam combat roles, the FAC pilots willingly faced the possibility of a lonely death every day.

Here are additional sources on the role of Forward Air Controllers in the Vietnam War and the 21st TASS:

21st Tactical Air Support Squadron

Forward air control during the Vietnam War

Forward Air Controller - History.net

Edmund F. Thornell was laid to rest on September 20, 1966.

Burial:

Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery

San Diego

San Diego County

California

Plot: PS-6 SITE 562

Grave marker for Edmund F. Thornell

Photo by Linda Claxton from the Find A Grave website

¹ WHAT NOW LIEUTENANT? An Infantryman in

Vietnam by Robert O. Babcock,

Deeds Publishing Company Marietta, GA 2008 pp. 104-109

Home | Photos | Battles & History | Current |

Rosters & Reports | Medal of Honor | Killed

in Action |

Personnel Locator | Commanders | Station

List | Campaigns |

Honors | Insignia & Memorabilia | 4-42

Artillery | Taps |

What's New | Editorial | Links |