![]() 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry

1st Battalion 22nd Infantry ![]()

The 22nd Infantry and the Moros - Introduction

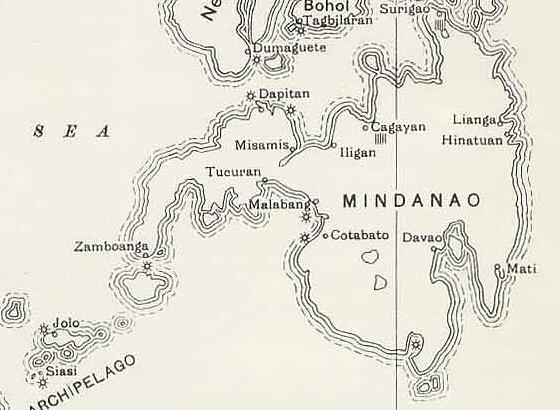

The southernmost main island of

Mindanao, and, to the left,

the Sulu Archipelago, containing the island of Jolo.

The 22nd Infantry would see duty in both places during the years

1904-1905.

(Ed., The following

passage is taken from the Regimental History of 1904.

It sets the stage for the second phase of the 22nd Infantry's

involvement

in the Philippines—the war against the Moros, the Muslim

inhabitants

of the southern Philippine Islands.)

THE MOROS OF LAKE LANAO

The Moros are descendants of the Musselman

Dyaks of Borneo. For centuries they have been the scourge of sea

and land,

pirates—where they could force a boat, ravaging hordes of

warriors where dry land barred their vintas. In their hearts

beats

the implacable hatred of the Moslem for the Christian.

Mohammedan feudalism and fanaticism balked all

attempts at Spanish conquest. The pride of Spain landed at many

ports of Mindanao

in the sixteenth century—freebooters whose thirst for fame

and gold has given the world its most gallant combats; but even

these intrepid warriors,

of a time but little later than that of Cortez and of Pizarro,

were not able to withstand the frenzied attacks of the Moro.

Spanish geographers

have handed down to us maps of a wilderness dotted here with a

Puerto, de Isabella, there with a Campo de Ferdinand. For a brief

space of time,

the glory of Spain was displayed at many points of Moroland;

shortly afterward, bleached bones

and medieval names on the map were all that remained of glory.

Late in the sixteenth century, Spain made one

final attempt to subjugate the Moros of the Lanao district. But

powder and firearms and armor

were no match for the kris and kampilan and wooden shield.

Bravery fell before fanaticism; science was routed by

overwhelming numbers.

Among the Moros of the present day occasionally one may find an

old helmet, or an old piece of mail, or an old blade—

these are the relics of Spain's disastrous attempts among the

Moros.

|

The central part of the The 22nd Infantry Besides garrison duty The 22nd fought in It also participated |

For two hundred and fifty years afterward, Moro

supremacy was absolute. Spain was obliged to remit taxes, not

only from Mindanao,

but from nearby islands. There was nothing to tax in the

neighboring islands: the Moros took everything. And thirsting for

a wider world for conquest,

Moro craft appeared in the bay of Manila early in the nineteenth

century; Moros sacked the entire western coast of Luzon; they

took into slavery

many Spaniards as well as Filipinos.

All in vain did succeeding governors-general

fit out expeditions to put an end to this piracy. Lured by

inducements of spoil, wealthy Filipinos

equipped expeditions. But all were in vain. Millions of money and

rivers of blood only served to increase the spirit of the

indomitable marauders.

It was not until 1860 that a fleet of steam launches succeeded in

confining the pirates to their own islands.

In 1895, Governor General Blanco, in person,

led an expedition against the Lanao Moros—the first that

Spain had attempted for three hundred years.

Gunboats, in sections, small arms, and great stores of war

materials were carried from Iligan, on the coast, to Lake Lanao.

For three months a land force attacked cottas at various points

while the gunboats shelled every stronghold that could be reached

from the lake.

The campaign was successful to a limited extent; the Spaniards

were enabled to hold Marahui at the north end of the lake, and to

control,

but not without strong escorts, the road from Iligan to the lake.

Moros claim that the Spaniards were never able to force an

entrance to Taraca,

the great Moro stronghold on the eastern shore of the lake.

Moro government is a complicated feudalism. The

Sultan of Jolo is the acknowledged head; under him are a

multitude of sultans,

each strong according to his power, his riches, and the number of

his wives. Under the sultans are dattos, likewise strong

as they possess wealth and women. Under the dattos are free

Moros; under all, sacopes or slaves. Religious rank includes

hadjis and panditas.

Civil rank is also established; but the officials of religion and

of the civil functions seem to be mere tools in the hands of the

sultans.

Each sultan of importance has his own priest, his own lawyer and

scribe.

(Ed., Moro chieftains were called Datu's. Period spellings of that title were "dato" and "datto".)

|

Datu Grandé He has a revolver in a holster The young boy next to the Datu Photo from the Parker Hitt photograph

collection, |

The greater part of the Moro territory around

Lake Lanao is swampy. In these swamps, the Moros have built their

cottas—rectangular earthworks,

ten to twelve feet high, surrounded by ditches, and surmounted by

close growths of bamboo. Only mountain batteries can be carried

over the marshy trails. Each cotta is plentifully supplied with

lantacas—small brass cannon firing slugs. Their rifles range

from flintlocks

to stolen Mausers and Krags. Native powder gives only short range

to their bullets, but the nature of the country and the character

of the defenses

preclude long range fighting. In addition, each Moro carries a

kampilan or kris and one or more daggers; those in authority

carry spears—

all deadly weapons in a hand-to-hand combat. Cottas fall only

when taken by assault, and in this sort of fighting the old

armament of the Moro

is vastly more destructful than the modern arm of the American.

In December, 1903, when the regiment was

assigned to station at Marahui, many of the surrounding sultans

and dattos professed friendship,

but in the majority of cases the friendship was of doubtful

character. The road between the seacoast and Marahui was declared

sacred; along this line

no American forces, however few in number, were to be harmed. In

return, Americans were to respect and protect the Moros of this

vicinity.

But south of Marahui, all around the lake,

there was not a place where Americans in small bodies were free

from attack. Taraca—and this included

almost the entire eastern shore of the lake—was openly

hostile. To Maciu, the head man of Taraca, also the name of the

tribe of Moros

inhabiting this district, had flocked all the bad characters of

the lake region, all renegades from other districts, all men that

had succeeded in stealing rifles.

These characters were bound together by oaths upon their Koran;

they were imbued with the fanatical and piratical enthusiasm of

the boldest

of their ancestors—the issue was between Moslem and

Christian.

Spain's attempts at conquest in the Lanao

district had merely strengthened the Moro's belief in his own

superiority. A circuit of the lake by Americans,

in which the rear guard had been constantly fired upon, had not

decreased this belief. The pride of sovereignty, centuries old,

was not to be humbled

by promises of better conditions. It could not be abased by a

mere showing of arms. Spaniards had come, had gone. After

hundreds of years,

when their advent had become a myth, Spaniards had come again,

and again they had gone. They had been followed by

Americans—in time,

why should not they, too, go?

This was the condition that confronted the regiment upon its arrival at Marahui.

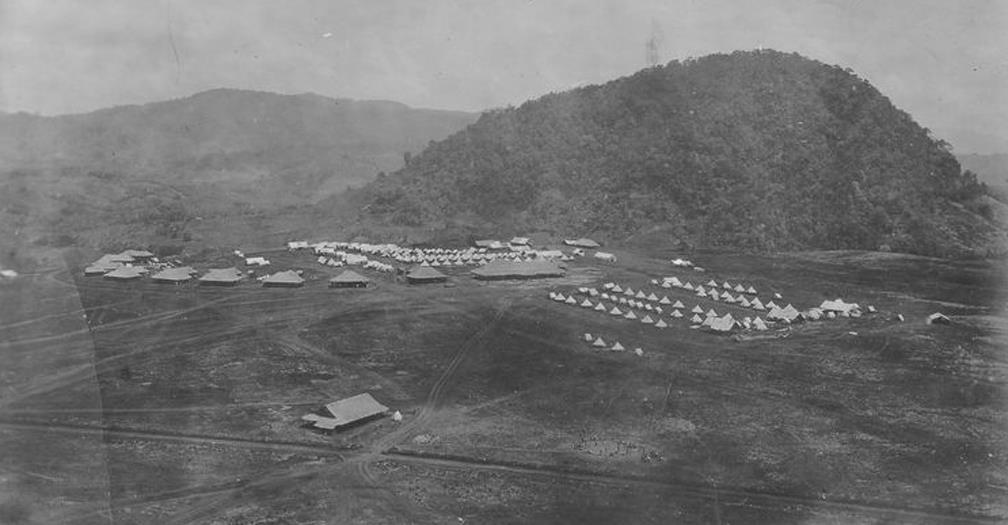

The 22nd Infantry camp at Marahui, island of Mindanao, the Philippines.

This photo appeared in the 1904 Regimental history

The following

passages were written by Colonel John White, who spent 15 years

as an officer in the Philippine Constabulary. His descriptions of

the people and places

of the southern Philippines during those times are still some of

the best ever done.

He paints a good

picture of what the 22nd Infantry faced in Mindanao and Sulu

(Jolo),

and indeed, he and his men sometimes worked with the 22nd on

operations.

In the Christian-Filipino provinces of Luzon

and the Visayas, the American Government had at least the

wreckage of Spanish administration

out of which to construct a government; but in Mohammedan

Mindanao and Sulu the Spaniards had left little or no heritage of

constructive government;

they had held but a few fortified towns on the fringe of Moro

populations still steeped in piracy, slavery, and superstition.

On the coast and on the lakes and rivers of

Mindanao, on every island of the Sulu Archipelago, strung like a

necklace of emeralds

from Mindanao to Borneo, were Moro sultans, rajahs, mflharajahs,

datus, panglimas, or hadjis, each ruling his little band of

gaudily dressed

and weapon-adorned fighting men. There were chiefs whose

followers could be numbered on the fingers of one hand; there

were others

who mustered thousands of retainers armed with modern rifles in

addition, of course, to the sharp kris or barong thrust in the

sash

of every Moro gentleman. But the leader of five men was as touchy

as the lord of five hundred; as quick to defend his ancient

prerogatives

of life and death over his dependents, and especially over the

pagan hillmen who inhabited, side by side with the Moros, the

jungles of Mindanao

and the larger islands; as ready to die to defend his right to

keep slaves and exact tribute from Subanuns, Bilanes, Manobos,

Bagobos, or Bukidnon.

Those are the names of a few of the dozens of pagan tribes that

inhabit the Mindanao mountains.

Mindanao, an island about the size of Ireland,

was almost a land unknown. Its rugged ranges of mountains

culminating in peaks

8000 and 10,000 feet high, its inaccessible and swampy lakes, its

rivers flowing through trackless jungles, its shores fringed by

mangrove swamps

and coral reefs, its gloomy forests and its glorious sunlit

grassy plateaus were mapped only in outline or by Spanish

draftsmen with vivid imaginations.

Here and there a Jesuit priest or a captain with some flickering

flame of conquistador spirit had journeyed into the interior to

return with tales

of magnificently retinued Moro chiefs or tribes of man-eating

savages. One thing the Spaniard had done—and there were not

lacking gallant pages

in the doing of it. They had stirred up the nest of human hornets

that inhabited the archipelago south of the eighth parallel of

latitude.

And now we were to persuade those hornets to return to their

burrows. But, despite fumigatory legislature, patience, and

constructive administration,

a good many Americans were to be stung to death before the

buzzing Mohammedan swarms calmed down; while even now an

occasional hornet escapes

and the American public reads, over its breakfast coffee, or more

often fails to notice, that "some renegade Moros in Sulu

have been subdued

by the Constabulary with the following casualties ..."

About the time that Christian missionaries were

starting west, Arab priests of the other great missionary

religion of the world, the Mohammedan,

started east from Mecca, through India, through the Malay

Peninsula, through Sumatra, Java, the Celebes, and Borneo, and so

on to the Sulu Islands,

Mindanao, and the Philippines. Upon the Malay seafaring folk of

the southern Philippines, the Mohammedan emissaries washed an

even thinner veneer

than that with which the Spaniards coated the northern Filipinos.

Another racial distinction must be borne in mind. The Filipino of

the North,

whether Tagal, Ilocano, Visayan, or Bicol, is of more mixed blood

than the Moro of the South, who is of pure Malay strain, the

leading families alone

having some of the blood of the Arab missionaries with a very

occasional infusion of Chinese. The Filipino, even at the time of

the Spanish Conquest,

was of mixed race, Malay and Indonesian diluted with Chinese and

other blood; and since the Spanish Conquest, the Filipino of the

North

has further attenuated the Malay strain. But the Moro is almost

pure Malay. His leading characteristics are those of the Malay:

fierce personal independence,

lack of respect for life and property, combined with much

dignity, pride, and courage.

Just as the American of the Western frontier in

the nineteenth century expressed the quintessence of the

Anglo-Saxon racial characteristics—individuality,

adventurousness, and the desire to build from fresh

material— so the Moro was the Malay frontiersman of the Far

East; in him the Malay traits blossomed

into a virile race with a leaning toward warfare and piracy as

national professions. ¹

The first part of

the 22nd Infantry's service in the Philippines ( 1899-1902 ) was

spent on the island of Luzon,

where Spanish influence had reigned supreme. The enemy was

reasonably conventional in its organizations

and tactics. The countryside was, for the most part, quite

civilized under Spanish rule for centuries.

And, in most of the major engagements , the battlefield consisted

of villages, towns and cities,

all connected by a network of railways and roads.

For the second part

of the 22nd's service in that region ( 1904-1905 ) , the areas of

operation were,

for the most part, just the opposite. Facing the Regiment was

wild and uncivilized country,

inhabited by a primitive and medieval people. Little or no

railroads existed. Main roads were often

nothing more than small jungle trails. Engagements were fought in

thick jungle, and at Moro cottas,

the earthen and bamboo forts built along the rivers, mountain

tops, or carved out of the jungle.

The enemy was unconventional in its organizations and tactics,

skilled in guerrilla warfare,

and unmatched in the ferocity of its attacks.

The environment was totally hostile to human life, as the following passage written by Colonel White illustrates:

Julian ran over to where a giant bamboo drooped

gracefully outward from the forest wall, and with a well-directed

slash of the talibong bolo

cut down a thirty-foot stem, while with a few more strokes he

made a sharp-edged stick about two feet long. I asked him for

what it was intended.

"Limatuk, po!" (Leeches, sir), he answered. We were to

enter a belt of forest infested with these blood-sucking pests,

so the soldiers and cargadores

also cut bamboo scrapers with which to remove them from bare

limbs. Then we dived into the forest.

The hard dry trail of the cogon was ended, and

now underfoot was dank leafy mold with rattan and other vines

crisscrossing the path,

festooning trees, climbing up toward the life-giving sun that

never penetrated the forest depths; and in the mold, on every

twig and leaf underfoot,

alongside or hanging from above, were the wretched limatuks,

which, though scarcely longer and thicker than a pin, would after

a few minutes' adhesion

to human skin swell to the size of a man's little finger. Every

little while I called a halt, to let the cargadores scrape

limatuks from their skin,

while the soldiers and myself removed our shoes, often to find

leeches that had wormed through eyelet holes or between folds of

clothing.

That is, some of the soldiers removed their shoes, for others

were still barefooted. Nothing kept the leech pests entirely out,

though when the Constabulary adopted woolen puttees we found them

almost complete protection. I discovered, too, that salt

liberally rubbed on socks

was a specific; but as mountain hiking involved wading of rivers

the salt soon washed off.

If the leeches got into nose, eyes, or ear, they were really

dangerous. Their bite anywhere on the body, if not rendered

aseptic,

might result in a frightful tropical ulcer as big as a dollar and

eating to the bone. ¹

The Soldiers of the

22nd Infantry faced an enemy who was brave, and determined to

prevent

any rule in their lands, apart from their own. Perhaps the most

formidable foe encountered by the Regulars

was the Maguindanaw chieftain, Datu Ali, who fought many battles

with the Americans, yet eluded capture

for two years, until a special company from the 22nd surprised

and killed him in his mountain hideout.

The following

passage written by Colonel John White illustrates the savagery

Datu Ali could visit upon

intruders to his part of Mindanao. Colonel White picks up the

narrative at the time when he first

came to the Cotabato Valley with his Constabulary forces:

Datu Ali was then some distance along the trail

which ultimately led to his grave. From his point of view a good

beginning had been made

when in May, 1904, he ambushed a company of the Seventeenth

Infantry and killed two officers and seventeen men. It was a

bloody little affair,

typifying the difficulty of campaigning against hostile Moros in

that part of Mindanao. The small company of about forty soldiers

had hiked through the almost trackless swamps at the mercy of a

faithless Moro guide, the officers ignorant of the terrain and

language,

yet gallantly leading their men into the heart of a hitherto

unexplored country. Mile after mile the trail led through the

high tigbao grass,

impassably interlaced on either side and often overhead, while

underfoot was the vicious black mud of a churned-up trail with

occasional holes

where the men sank to their waists. Then there was a sudden spurt

of rifle fire from ahead, from either side, from an invisible

enemy

secure behind the maddening wall of matted, canelike grass. The

men in advance fell dead and dying in the stinking mud.

The officers pressed forward, and, in like manner, were mown down

without seeing the foe. The remnant of the expedition

withdrew in disorder while the victorious Moros with vicious kris

and barong completed their work by beheading

and disemboweling the dead and dying Americans. ¹

**********************

¹ BULLETS and BOLOS Fifteen Years In The Philippine Islands

by John White

The Century Company, New York & London 1928

Home | Photos | Battles & History | Current |

Rosters & Reports | Medal of Honor | Killed

in Action |

Personnel Locator | Commanders | Station

List | Campaigns |

Honors | Insignia & Memorabilia | 4-42

Artillery | Taps |

What's New | Editorial | Links |