![]() 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry

1st Battalion 22nd Infantry ![]()

Gunboats on Lake Lanao 1904-1905

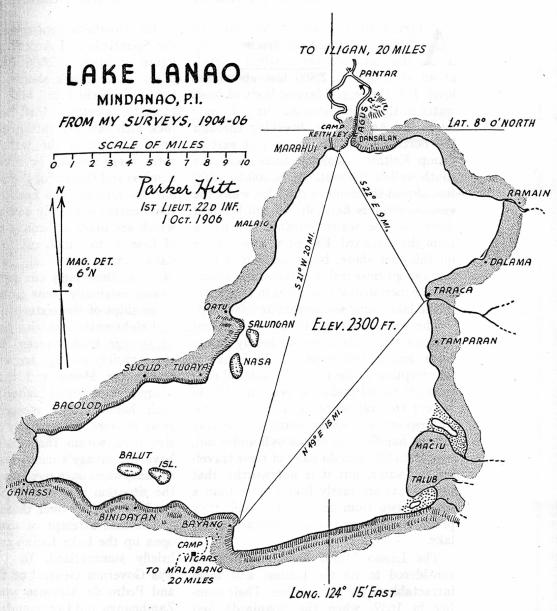

Map of Lake Lanao drawn by 1st LT Parker Hitt of the 22nd Infantry

From Amphibious

Infantry A Fleet On Lake Lanao by Colonel Parker

Hitt,

US Naval Institute Proceedings 1938

The following article

appeared in the US Naval Institute Proceedings,

February 1938.

It was written by Parker

Hitt, who, as a 1st Lieutenant in the 22nd Infantry,

was instrumental in raising the sunken Spanish gunboats General

Almonte and Lanao

from the bottom of Lake Lanao, on the island of Mindinao, 33 to

34 years earlier.

Thanks to Robert A. Fulton, the author of:

MOROLAND

The History of Uncle Sam and the Moros

1899-1920

for submitting the article to the 1st Battalion website.

Parker Hitt, as a young Infantry Officer

From the Parker Hitt photograph collection, University of Michigan

AMPHIBIOUS INFANTRY

A FLEET ON LAKE LANAO

By COLONEL PARKER HITT, U.S. Army (Retired)

A little to the west of the

center of Mindanao lies Lake Lanao, filling the crater of a vast,

extinct volcano at an elevation of 2,300 feet above sea level.

It is the second largest body of fresh water in the Philippines

and its only outlet is the Agus River, breaking through the north

wall of the crater

just east of Camp Keithley. Twenty miles away the south wall of

the crater rises 800 to 1,000 feet almost sheer out of the lake,

while the eastern shore

is flat, alluvial soil brought down by the many streams flowing

in from the eastward. Except at some places on this east shore,

boats drawing 4 to 6 feet

can go close inshore almost anywhere. Some experimental soundings

in the center of the lake found no bottom at 1,000 feet. The wind

is always tricky,

and violent at times, over waters surrounded by mountains, and in

this respect Lake Lanao is no exception to the rule. The rainfall

runs from 60 to 80

inches a year, mostly in violent tropical showers, and formidable

waterspouts are not uncommon. The lake natives handle their

vintas well under sail,

oar, or paddle and do most of their traveling by water, but it is

noteworthy that their boats are rarely found more than a mile or

two from shore.

As a rule, they prefer to go around rather than across the lake.

The Lanao Moros have always been

considered to be the wildest and most intractable of the Moro

tribes. Their number in 1639,

when the Spaniards first reached the lake, is not known but there

were settlements all around its shores. At the end of the

nineteenth

and beginning of the twentieth centuries, estimates by the

Spaniards and Americans agree on a figure of about 15,000 living

within 5 miles

of the lake's shores. There are no towns; each chief and man of

any importance has a cotta or fort, built of earth or rock with

bamboo, rattan vines,

and even trees growing in the walls, and in this cotta there are

one or several houses of bamboo and thatch for the man, his wives

and his retinue.

The heavy armament of these cottas is usually several

"lantakas" which are brass or bronze muzzle-loaders of

from 1- to 3-inch caliber, loaded with nails,

scraps of metal, or even stones. Many of these guns are genuine

antiques, having originally come from Spanish and other ships of

the sixteenth,

seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries as piratical loot or

salvage from wrecks. Small arms of every variety and age are

widely scattered among the Moros

and the twisted kris (dagger) and broad-bladed kampilan are their

hand-to-hand weapons. They are good fighters, particularly on the

defensive

from within their cottas, and they have the savage's usual

respect for force so that, when once overcome, they accept the

situation

and make no more trouble until the control over them weakens.

The first attempt of the

Spaniards to open up the Lake Lanao country may be briefly

summarized. In 1639, Corcuera was Governor General

of the Philippines and Pedro de Almonte was Governor of Zamboanga

and Commandante General of the Islands of the South. They were

both

energetic soldiers of the type that had made Spain mistress of

new worlds, and rumors of the great lake in the center of

Mindanao were enough

for them to give orders for an expedition to investigate,

conquer, and Christianize the place. The force of about a

thousand, under the joint command

of Francisco Atienza, an experienced soldier, and Fr. Agustin de

San Pedro, a fighting priest, made its way up to Lake Lanao from

the north

carrying six boats "which were carried cut in four pieces

with such skill that they could be easily assembled for

launching." On April 4 they set foot

on the margin of the lake without having any trouble. They

assembled their six sectional boats and by land and water marched

right around the lake,

receiving the surrender of the various chiefs and holding

ceremonies of allegiance "in which they enrolled more than

2,000 families."

The priest wanted to put a permanent garrison in a fort on the

lake but the native troops would not consider the idea and the

expeditionary force

returned to their seacoast towns after a pleasant three months'

jaunt. Later that year another expedition from the south coast

marched through

the lake district without resistance from the inhabitants and

reached the north coast at Iligan.

Governor Corcuera in Manila,

after hearing the reports of these expeditions, ordered Bermudez

de Castro with 50 Spaniards and 500 native troops

from Bohol to go up to the lake, build a fort, and garrison it.

The lake Moros by this time were thoroughly aroused and organized

and from the very beginning of its construction the fort was

besieged and attacked. A relief column, commanded by the

redoubtable

Fr. Agustin de San Pedro, rescued the garrison from certain

extermination. Both commanders saw that the fort could not be

maintained

against the hordes of Moros who were bent on its destruction, so

they demolished what they had built with so much labor and

bloodshed

and retreated to Iligan on the north coast. The detachment was

there provisioned and returned to Bohol and Manila.

It is almost unbelievable, but after these expeditions of 1639

and 1640 no Spaniard laid eyes on Lake Lanao for more than 250

years.

The seat of Spanish authority in

Mindanao was at Zamboanga all these years, but every attempt to

Christianize even the coast town Moros

was a failure and their allegiance to the Spanish crown was

purely nominal. After 1880, the Manila government began to plant

colonies

of Christian Filipinos from the northern islands at points on the

north coast of Mindanao, with the idea of cutting off the sea

raids

of the piratical Moros which had occasionally even reached Luzon.

The plan, in conjunction with a naval patrol of the coast,

was reasonably successful but was hard on the colonists for the

Moros turned on them instead. The colony at Iligan, 25 miles

north of Lake Lanao,

suffered especially from the bold raids of the Lanao Moros. The

Manila authorities finally decided that the raiding would have to

be stopped

or the colonizing plan would have to be given up. An expedition

against the Lake Lanao Moros appeared to be the solution.

Plans for this expedition were

formulated in 1894, under the direction of Governor General Ramon

Blanco. As a part of the plans,

contracts were let in Hongkong for the construction of two steel

gunboats. They were to be shipped in pieces of the least possible

weight,

to permit of their transportation to Marahui on the lake, and

were there to be assembled by the constructing firm with their

engineers and personnel.

They were to have a speed of 10 miles per hour and capacity for

transporting 80 men. Their armament, contracted for with

Nordenfelt of London,

consisted of a 42-mm. rapid fire gun in the bow, two 11-mm.

machine guns amidships, and one 25-mm. machine gun, firing steel

projectiles, in the stern.

They were 92 feet long, 15 feet beam and drew 6 feet, and had a

single Scotch boiler and twin screws, each driven by a compound

noncondensing engine.

The powerful and well-equipped

expedition reached Marahui on Lake Lanao in March, 1895, after

severe fighting and heavy losses in personnel.

There was little further trouble with the Moros living along the

Iligan-Marahui trail but those who lived in the settlements

around the lake

continued their defiance and their attacks on the invaders. The

work of fortification was begun, as well as the construction of a

broad

and unobstructed road from the coast to Marahui. For the purpose

of transporting the sectional gunboats to the lake, there were

available

some 2,000 cargadores who were paid at the rate of a half peso a

day. The task of transporting the parts of the gunboats,

assembling them,

and launching them in the waters of the lake was directed by Sr.

Bringas, Naval Engineer of the Spanish Fleet. The construction

company

sent from Hongkong two English engineers and 100 Chinese workmen

for the assembly job.

The market place on the Lake at Marahui, early 1900's.

Photo from Amphibious

Infantry A Fleet On Lake Lanao by Colonel Parker

Hitt,

US Naval Institute Proceedings 1938

photo credit given as Colonel Parker Hitt

During the summer of 1895, a

further contract was let to the same firm in Hongkong for two

single-screw 65-foot gunboats

and three iron barges, each with a carrying capacity of 200 men.

This whole order was to be transported in pieces to Marahui

to be assembled and launched there. The barges were of an

excellent design for carrying troops for rapid disembarkation at

points on the lake shore.

They were 60 feet long, 20 feet beam, and drew but 2 or 3 feet of

water when loaded. They had a raised and decked-over forecastle

and a similar structure aft, while the midship section, about 40

by 20 feet, was fitted with removable benches and covered with an

awning.

They towed and handled well and could be maneuvered by man power,

for which oars and oarlocks in the rail were provided.

On August 18, 1895, the first of

the twin-screw gunboats was launched and, toward the end of

September, the second.

The trial trips gave all the results expected as to speed,

convenience, and maneuverability. The first warlike service of

the boats

was the reconnaissance carried out on October 16 to the south

shore of the lake and the bay of Ganassi by the Commanding

General in person,

accompanied by his Chief of Staff and the Division Commander. For

the next three months, combined action by land and water struck

terror

into the Moro tribes of the lake region. Their cottas were

attacked and destroyed, their movements on the lake were stopped

and, in general,

the operations were a complete success. The arrival and erection

of the two smaller gunboats and the three troop-carrying barges

during the winter

of 1895-96 gave the Spaniards such a preponderance of power on

the lake that they had no further serious trouble with the Moros

for the next three years.

The end of the Spanish

domination of Lake Lanao came as a result of the Spanish-American

War. Of the sinking of the fleet there is no record,

as far as can be discovered, but the facts as related some five

years later by Moro eyewitnesses are substantially as follows:

Some time in November,

1898, orders were received at Marahui for the post to be

abandoned and for the garrison to proceed to Iligan for

transportation to Zamboanga

and ultimately to Spain. As a result of these orders, the

garrison worked feverishly for three days, loading all

noninflammable stores and supplies

into the steel barges. They were particularly careful to remove

all metal objects, including the machine tools from the shops,

the contents

of the storehouses, and the rails and cars of a short section of

light railway which had been installed. The guns were removed

from the gunboats

and their bunkers were filled, about exhausting the stock of coal

ashore.

On the evening of the day when

this task was completed, the Moros saw steam being raised on one

of the larger gunboats

and about nine o'clock at night it pulled out from the dock with

the three other gunboats and the three barges in tow. Some hours

later

a single small boat carrying six men landed on the dock and went

into the guard's blockhouse. The post was put to the torch early

the next morning

and the garrison started on its march to Iligan to await its

ultimate return to Spain. The accuracy of this story is confirmed

by a singular bit of evidence.

Some seven years later, when we raised the Lanao, one of the

twin-screw gunboats, her boiler-room gratings were littered with

fire tools

and the remains of drawn fires and in the rack on the cabin table

were six champagne glasses and an empty champagne bottle.

I still have five of these glasses, mute witnesses to a hard task

well performed.

Except for the occupation of

Jolo and Zamboanga, the Americans did little in Mindanao until

1902. Events in the northern islands

required all available troops from 1898 until that year; the

Moros, no longer under Spanish discipline, followed their usual

line of action and,

after a time, began again to raid the settlements of the

Christian Filipinos along the Mindanao coast line. In 1902 the

28th Infantry

was sent to Iligan and had penetrated to Lake Lanao before the

year was out. The 14th Cavalry built a new post called Camp

Overton

just west of Iligan in 1903. That year, Major (now Lieutenant

General) Robert L. Bullard with the 28th Infantry and thousands

of natives

cut out the forest growth and rebuilt the old Spanish trail to

Lake Lanao so that it was passable for army wagons.

Early in December, 1903, the 22d

Infantry, in which I was a first lieutenant, relieved

the 28th Infantry. One battalion of the regiment

was stationed at Pantar at the bridge over the Agus River while

the rest of the regiment built Camp Keithley on the site of the

Spanish post.

The ruined boulder docks at the lake and road up to a lookout on

a hill were the visible remains of the Spanish occupancy.

One of the pressing needs of the garrison was water

transportation for use on lake. The 28th Infantry had built ten

crude flat-bottom boats

that would hold possibly ten men each but they were cranky and

unseaworthy. Nevertheless we used them and six or eight Moro

vintas

in the expedition against the Ramain River cottas in January,

1904, and again in the Taraca River expedition of April of that

year.

Captain Peter W. Davison (now deceased) was the Post

Quartermaster, charged with buying bamboo and other material from

the Moros

for building the new post, and he soon heard stories from them

about the fleet of gunboats that the Spaniards had sunk in the

lake.

One old Moro chief even had some marks on trees near his cotta at

Dansalan which he claimed gave intersecting lines of sight on a

point

where oil and floating debris had come to the surface after the

sulking. Following these clues and others, Captain Davison and

Lieutenants

Martin Novak and Dean Halford of the regiment finally got a

definite location of one of the boats about 2 miles south of the

dock in 90 feet of water.

This was on February 23, 1904, but much had to be done before any

use could be made of the find.

Ed., In his expeditions around

Lake Lanao in the fall of 1902 and early 1903, Captain John J.

Pershing

had previously marked down potential sites of the sunken boats.

¹

We finally got our first power

craft about the middle of April, after the Taraca expedition. It

was a 28-foot steam launch

(condemned, I always believed), off the Army hospital ship Relief,

then stationed in Manila. The hull came up the 2,800-foot climb

from Overton on an extemporized rig drawn by eight mules. Engine,

boiler, fittings, coal, and other supplies followed in other

wagons.

Within two days we had the Relief, as we always called

her, in the water with all machinery installed, all gadgets in

place,

and painted within an inch of her life. A formal trial trip,

planned for the next day, never came off for General Leonard Wood

arrived

and wanted to go across the lake so we just got up steam and

went. The littly hussy had a tricky water-tube boiler, a

compound,

condensing engine, and an unbelievable appetite for coal and

lubricating oil. After three years of hard and faithful service

her engine failed one day

as she was leaving the dock and she drifted onto the rocks at the

mouth of the swift Agus River and was hopelessly wrecked.

|

A 28-foot steam launch, of

the same type Photo from: |

Even before the Spanish gunboats

had been tentatively located, our need for at least one armed

vessel on the lake had been taken up

with Army Headquarters in Manila and early in May of 1904 it

arrived in boxes, bundles, and bales, accompanied by the erection

engineer

for the Shanghai builders, Mr. Turnbull, and 100 Chinese

laborers. This was the Flake, named after one of our

officers killed in action

in the Ramain expedition. She was 65 feet long, 12 feet beam, and

drew about 4 feet of water. We had already built and launched

two wooden decked barges for raising the Spanish boats, so there

was no delay in building ways for her erection and the work went

ahead fast

under Mr. Turnbull's able direction. She was launched on June 20

and had her trial trip on July 3. With her Scotch boiler and

compound

noncondensing engine she was a fine sturdy boat, well fitted for

the towing of barges and log rafts for our saw mill.

I mounted a Vickers Maxim 37-mm. automatic gun (pom-pom) in her

bow and a 45-caliber Gatling gun aft, and thus armed

she was the "Dreadnought" of the lake for many a month.

Her crew of five (all Manila Bay Filipinos) ran her under my

supervision

and kept her in apple-pie order, no matter what dirty work was

demanded of her.

The 65-foot gunboat Flake,

named after Lieutenant Campbell W. Flake of the 22nd

Infantry,

killed in action at Ramaien River, Mindanao, January 22, 1904.

At the bow can be seen the Vickers/Maxim 37mm automatic gun that

was mounted by Lieutenant Hitt.

Photo from the Parker Hitt photograph collection, University of Michigan

About this time the route by

road from Camp Overton to Camp Keithley, then by boat across Lake

Lanao to Camp Vicars,

and finally by road again to Malabang, became a well-traveled way

between Manila and Zamboanga and Jolo. We also had

a two-company garrison, frequently changed, at the mouth of the

Taraca River, and as soon as she was finished the Flake

immediately went

on a daily schedule to handle the traffic over the route

Marahui-Taraca-Bayang-Marahui.

One day in late September the

Commanding Officer sent for me and told me that the Sultan of

Oatu, who lived on a beautiful bay

of the same name, about halfway along the northwest shore of the

lake, had sent word that he had "a bad heart" for the

Americans

and that we had better keep away from his district. The C. O.

directed me to drop into the bay and see what would happen.

I took on nine picked rifle shots from the regiment in addition

to my Filipino crew of five, mounted a .30-caliber Colt machine

gun

in addition to the other armament and went to see. As the Flake

rounded the point to enter Oatu Bay, all was quiet ashore.

Then long, red Moro streamers broke out from poles around the

sultan's house and on the hillsides, and 50 or 60 riflemen let go

at the boat,

fortunately still about 600 yards away. Most of the shots fell

short but three hit the boat. They had little smokeless powder

and we went into action

at the clouds of white smoke ashore. Then from a stone fort high

on the hill and about 1,000 yards off came a shot from a 6-inch

muzzle-loading cannon that struck the water about 200 yards

beyond us. It was a kind of opera bouffé battle. We cruised

around

in the landlocked bay until all our ammunition was gone; the

Moros fired the big gun twice more but the last shot barely hit

the beach

from lack of powder. Their rifle and lantaka fire practically

ceased after the first few volleys. The net result was four hits

on the Flake;

one of our shells set fire to the sultan's house and we heard

later that two Moros had been wounded.

When I reported on our return,

the Commanding Officer was pretty mad. An expedition against Oatu

was in order and,

after some delays due to politics (it was an election year in the

United States), it was launched. The Flake towed a barge

full of troops down the lake; other troops, including a mountain

battery, closed in from the land side and the entire settlement

was destroyed

with numerous casualties; the survivors fled to the mountains

and, some weeks later, the sultan came in voluntarily and made

his peace

with the authorities. That was the last major trouble on Lake

Lanao for five years.

When the sunken Spanish boats

were located in February, 1904, Captain Davison immediately made

arrangements to salvage them if possible.

Early in March, Mr. Frederick J. Davies, an experienced deep-sea

diver, arrived to take technical charge of the job.

He was an Englishman, possibly 50 years old, whose proudest boast

was that he was one of the four divers who got the treasure

out of the Spanish liner Alfonso XII, sunk in 240 feet

of water in the Bay of Biscay. The other three divers died as a

result of their work;

Mr. Davies was still suffering with the "bends" brought

on by that hitherto unparalleled feat of deep-sea diving.

Two soldiers of the regiment,

one of whom had had experience in harbor diving, and a large

force of Filipino workmen formed Mr. Davies's crew.

They built two decked-over barges of wood for the work and

assembled a storehouse full of anchors, hawsers, winches, and a

thousand other things

that might be needed on the job. By April 26, all was ready and I

towed the barges out to the buoys marking the position of the

sunken boats.

Then followed a month of work getting the bow and stern lines

under one of them. The water was fresh but murky, so that at 90

feet there was no light;

also the bottom temperature ran from 80 to 90 degrees Fahrenheit,

owing to hot springs. There was no tide to lift the boat after

the slings were in place,

and that important part of the work had to be done by man power

through the medium of four big hand winches.

Late in May the southwest

monsoon began to blow and for days work was suspended and it

became a problem to get food to the guard

on the barges. It was not until July 19 that the lifting proces

was successful in raising the boat out of the mud. On the 23d she

was lifted 47 feet

and towed in 1¼ miles, when a tackle broke and she dropped about

5 feet onto jagged rocks. On August 3 the funnel appeared,

and by this time we knew that she was the General Almonte,

one of the single screw 65-footers.

I will not go into the details

of the troubles we had in getting the General Almonte

out of water and up on the ways. Sufficient to say

that it was October 14 before this part of the task was

completed. After that, her bottom had to be repaired, her

machinery had to be

completely overhauled, she had to be made livable again with new

carpenter work and paint and awnings, so that she was not

launched

until December 12. On the last day of 1904 she had her trial trip

and thereafter she ran regularly in the Marahui-Taraca-Bayang

service,

while the Flake towed logs and bamboo rafts for the

construction of the permanent quarters of Camp Keithley.

It was February 13, 1905, before

the necessary heavier equipment was assembled and the barges were

towed out to where the Lanao lay.

Mr. Davies had been down to look her over several times in pauses

in the work on the General Almonte and he and I both had

serious doubts

as to whether this 92-foot boat could be raised with our

available barges, but it was decided to try anyhow. She lay in 95

feet of water,

about 2 miles out in the lake. Within two months, slings had been

put under her and she had been raised 25 feet and moved in about

600 feet

by slow and cautious stages. At this point, Mr. Davies found the

way blocked by one of the 60-foot steel barges, loaded with the

contents

of the Spanish machine shop. He made a careful examination of it

and reported that it was in perfect condition, so work on the Lanao

was stopped for the time being and the lifting pontoons were

shifted to the sunken barge. It was our one easy job, for within

40 days

the barge was afloat and lying at the dock, undamaged after lying

at the bottom of the lake for 6½ years. The cargo included

quantities of light rails, some cars, machine tools, and shop

supplies that, in spite of their condition, were a welcome

addition to our limited stocks.

I remember particularly a box of gauge glasses for the boilers,

that being an item that we could not seem to get on requisition

from Manila.

When the barge was cleaned out

and painted, it made a fine addition to the fleet as it would

carry as many as 200 troops, it towed well,

and its light draft made it possible to beach it almost anywhere

around the lake so that the men did not have to be landed in

small boats.

Also Mr. Davies had an eye on it for possible use in case his

pontoons would not give the final lift to the Lanao.

After the barge was out of the way,

work on the Lanao was resumed and by using the last inch

of displacement on the pontoons she was finally brought to the

dock head

with her rail out of water. That was on September 25, but during

the night a gale blew up, the port pontoon sunk under its load,

and the whole job

was just an ugly wreck by morning. Fortunately we could work, in

part, from the dock, so that the Lanao was finally free

and afloat within ten days.

Her bottom was undamaged, the only underwater damage being a bent

blade on the starboard propeller which had to be removed for

straightening.

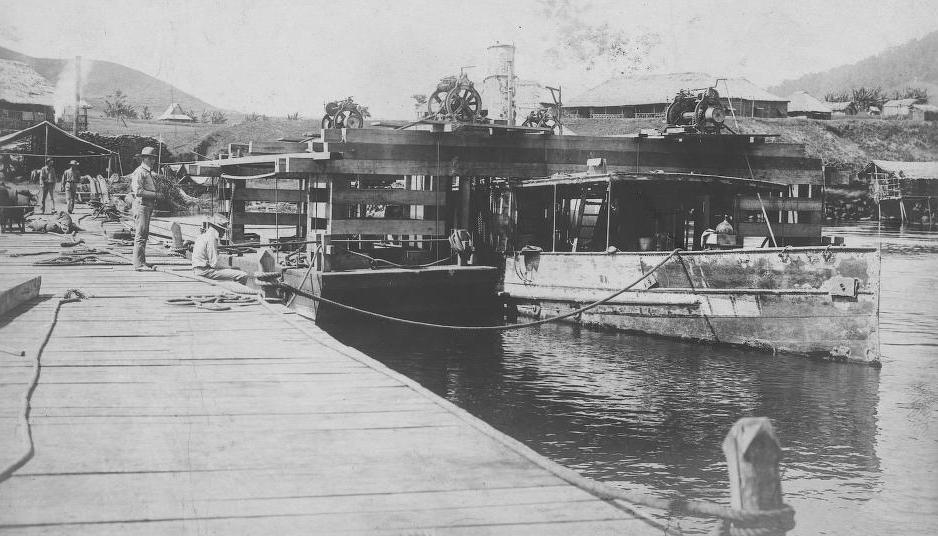

The Lanao,

after being raised and refloated. The two barges are still on

either side of the Lanao,

and all four hand-cranked winches used to raise her can be seen.

Photo from the Parker Hitt photograph collection, University of Michigan

Mr. Davies went off for a long

delayed vacation and rest after the Lanao was floated

but the next three weeks were very strenuous for the rest of us.

For some reason that has slipped my mind the Commanding Officer

wanted her ready by November 1, so work went on day and night.

The mud was removed from the hull and it was painted with red

lead inside and out; both engines were taken down and all pits

and grooves

in the moving parts made good with babbitt metal; all gaskets for

engines, pumps, boiler, and sea valves were replaced with new

ones cut out by hand;

all decks, cabins, and other woodwork were overhauled; the awning

stanchions were straightened and new awnings made and stretched;

the steering gear from wheel to rudder was put in order; the

davits were replaced and two new boats slung on them; and finally

the boiler was tested to 150 lb. cold, steam was raised, and the

engines turned over. The guns had been removed by the Spaniards

and we had nothing to go on the gun mounts except a Vickers Maxim

37-mm. automatic, but that was duly mounted.

For days we had been looking for

a shipment of white paint to cover the glaring first coat of red

lead. By October 25, all else was ready

but the paint had not arrived, so we decided to have the trial

trip the next day, paint or no paint. It was an entire success in

every way.

When the Moros saw the resurrected Lanao steaming down

the lake, painted in the Moro war color, and heard her gun being

fired,

they took to the hills by the hundreds. The Civil Governor of the

Moro Province had to send out special couriers to assure his

people

that they would not be wantonly attacked, but it was not until

the Lanao was painted white a week later that they felt

safe again.

The 15th Infantry relieved the

22d Infantry in December of 1905 and I turned over the fleet to

my old friend, 1st Lieutenant A. Owen Seaman

of that regiment, now Brigadier General, Assistant to the

Quartermaster General. I stayed on for a month after my regiment

left, to show him the ropes,

and then returned to the United States.

During the next two years all

the rest of the sunken Spanish boats were raised under Lieutenant

Seaman's supervision. First the two other steel barges,

which had already been located, were floated and then these

barges were used to raise the General Blanco, a

twin-screw sister-ship to the Lanao.

The General Blanco, through a combination of luck and

skill gained by experience, came up in perfect condition as to

hull, machinery, and fittings.

She was in running order before the end of 1906 was armed with a

42-mm rapid-fire gun forward, a 37-mm automatic aft, and five

30-caliber

Maxim machine guns amidships and on the upper deck. She became

the one "battleship" of the fleet and served honorably

in the Sauir

and Malaig expeditions against Datu Ami Binaning in 1907. A good

ship, for after 12 years' service as a fighting craft, she was

turned over

to the Provincial Government of Lanao in 1918 and still continues

to make bi-weekly trips around the lake in this year 1938.

She is the only one of the fleet still afloat and running.

The last of the sunken fleet to

be was the Corcuera, 65-foot sister-ship to the General

Almonte. She was never put in running order

on account of serious damage to her rudder and propeller which

happened when she went down. Also, by that time,

the Army had all the Navy that it needed on the lake to keep the

peace.

Thirty years have passed since

those days but the Lanao Moros are still a problem for the

Philippine government. Only last April

a band of Moro outlaws intrenched themselves in Cotta Macaguiling

between Binidayan and Ganassi on the south shore of the lake

and proceeded to terrorize the inhabitants of the vicinity. The

garrison of the new Philippine Army at Camp Keithley organized an

expedition,

embarked it on the faithful General Blanco and proceeded

to the south shore where they landed and abolished the gang and

the cotta with trench mortar fire.

Times change; the Moros remain Moros.

**********************

The dock and guardhouse area at Marahui

on Lake Lanao.

Under the light-colored canvas cover are the two barges used in

the raising of the sunken Spanish gunboats.

Note the two Soldiers of the 22nd Infantry guarding the bridge to

the area.

Photo from the Parker Hitt photograph collection, University of Michigan

The stern end of the Lanao,

with workers aboard.

The boat is still connected to the winching system by which she

was raised.

Note the handles for cranking the winches; one on each side, two

men cranking each winch at the same time.

Photo from the Parker Hitt photograph collection, University of Michigan

Stern view of the Lanao, after the winching system had been disconnected.

Photo from the Parker Hitt photograph collection, University of Michigan

Bow view of the Lanao, prior to being refitted and repainted.

Photo from Amphibious

Infantry A Fleet On Lake Lanao by Colonel Parker

Hitt,

US Naval Institute Proceedings 1938

photo credit given as Colonel Parker Hitt

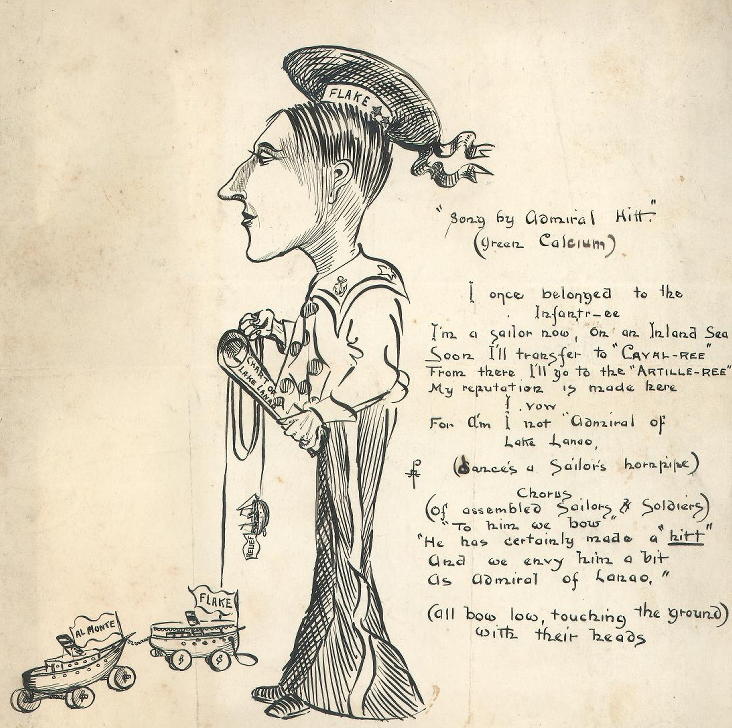

Caricature of Lieutenant Parker Hitt,

being portrayed as "Admiral of Lake Lanao".

Note that his toy boats include the Almonte,

Flake and Relief.

Illustration from the Parker Hitt photograph collection, University of Michigan

¹ Robert Fulton, author of MOROLAND The History of Uncle Sam and the Moros 1899-1920

**********************

Home | Photos | Battles & History | Current |

Rosters & Reports | Medal of Honor | Killed

in Action |

Personnel Locator | Commanders | Station

List | Campaigns |

Honors | Insignia & Memorabilia | 4-42

Artillery | Taps |

What's New | Editorial | Links |