![]() 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry

1st Battalion 22nd Infantry ![]()

The 22nd Infantry at Fort Keogh

1888-1896

An unidentified soldier of Company D

22nd Infantry at Fort Keogh circa 1888-1896.

He wears the Model 1872 forage cap with Model 1875 insignia for

Company D 22nd Infantry.

Photo by L.A. Huffman taken at his studio at Miles City, Montana

In December of 1983, Josef James

Warhank presented his Thesis

"Fort Keogh: Cutting Edge of a Culture", as requirement

for his

Master of Arts degree to the University of Southern California.

Warhank's narrative covers every

aspect of Fort Keogh's military history, from its establishment

in 1876 to its closing down by the Army in 1908. He recounts not

only the campaigns fought

by Soldiers from the post, but details their everyday life at the

post, both in war and peace.

His coverage is complete, including training and routine duty,

transportation and communication,

social life both on and off post, families of the Soldiers, the

fort's impact on the surrounding area,

and the legacy left behind, for successive generations, of Fort

Keogh's role in the westward

expansion of the country.

His work remains as possibly the

best chronicle of military life at a frontier Army post

during the latter part of the nineteenth century, a period known

in Army history

as the Indian Wars.

As early as 1876 detachments of

the 22nd Infantry Regiment were stationed at Fort Keogh.

In 1888 the Regiment officially took over the Fort and was the

principal unit there until June of 1896,

when the Regiment was transferred to Fort Crook, Nebraska.

The following passages dealing

with the 22nd Infantry are taken from "Fort Keogh: Cutting

Edge of a Culture",

and though taken out of context, give a remarkable glimpse of

what life was like

for the 22nd Infantry Soldier stationed there.

The website editor has added certain photos, illustrations and comments.

( Ed., From May through September of

1873 Colonel David S. Stanley, commanding officer of the 22nd

Infantry Regiment

led the third expedition into the Yellowstone country. It was a

large force, consisting of twenty companies of infantry,

which included the Regimental Headquarters and five other

companies of the 22nd Infantry, ten troops of cavalry

and a detachment of Indian Scouts. The expedition traveled from

Fort Rice, North Dakota, deep into Montana

to the Musselshell River, and then back to Fort Lincoln, North

Dakota. )

"Colonel D. S.

Stanley in 1873 led an expedition past the site that was to

become Fort Keogh, Montana. He reported on the condition

of the Indians about supply and ordnance. Due to these reported

conditions Stanley recommended that a post be built

at the mouth of the Tongue River, as it was located in the middle

of the Indian country and could supply smaller posts in the area.

Colonel Stanley's choice of a site was a good distance up the

Yellowstone." 1p6

"After Lieutenant Colonel George A.

Custer and a large part of the Seventh Cavalry lost to the Sioux

in June of 1876,

the conditions were right for a post at the site that Colonel

Stanley recommended." p6

( Ed., The 5th Infantry under Colonel

Nelson Miles built the fort and were stationed at it from 1876

until 1888,

when they were transferred to Texas, and the 22nd Infantry took

over the fort. At that time

the 22nd Infantry Regiment was commanded by Colonel Peter T.

Swaine.)

"Colonel Peter T.

Swaine was the last of the significant commanders at Fort Keogh.

Colonel Swaine brought

the Twenty-second Infantry, his regiment, from Colorado to Fort

Keogh in 1888 and was well received by the townspeople.

Due to Swaine's sickness, caused in part by his advanced age,

temporary commanders often led Fort Keogh,

but the Colonel still had a considerable impact on the Post. It

was in large part his efforts that stopped Coxey's Army

on its march to Washington after it had taken over a train.

Colonel Swaine commanded the Post during the buildup

in preparation for the campaign against the Sioux uprising of

late 1890. The command of the Department of Dakota

was sometimes entrusted to Colonel Swaine as the ranking colonel.

Colonel Swaine retired from the service

while at Fort Keogh. He had a full-grown family with a daughter

(who had a close relationship with Lieutenant Edward Wanton

Casey of Indian troop fame), and a son who was a young officer in

the Twenty-second Infantry as well.

When age caught up with Colonel Swaine in 1894, he was put on the

retired list and other less colorful men took over."

p77

|

General Order Number 12,

22nd Infantry, The first order signed by Lt.

M.C. Martin Martin served as Adjutant from He replaced Lt. W.H. Kell, The order also appoints Lt.

R.N. Getty Getty served as Quartermaster

from |

( Ed., The following excerpts concern

Casey's Cheyenne Scouts. Organized as an official part of the US

Army, they were given the title

of Troop L 8th Cavalry. They were formed and led however, by an

Infantry Lieutenant, Edward Wanton Casey,

of the Twenty Second Infantry. Indian Scouts had been used by the

Army for a number of years, but Casey was the first

to insist that his Scouts follow Army discipline in matters of

dress, conduct and operations. )

"Indian scouts took

part in all the major battles and most of the small encounters

that the troops at Fort Keogh had.

Authority to enlist Cheyenne scouts came from higher

headquarters, but their enlistment was not on the same basis as

the non-Indian

enlistees. The scouts did not have to adhere to the same

discipline. This situation was changed when the Twenty-second

Infantry

with Lieutenant E. W. Casey returned to Fort Keogh in 1888.

Colonel Peter J. Swaine read a report on efforts at using Indians

as soldiers.

As commander of the Twenty-second Infantry, Swaine decided to

form a troop made up of Cheyenne Indians. After permission was

received

from the commissioner of Indian affairs, Swaine directed

Lieutenant E. W. Casey to proceed. Casey believed that

Cheyenne Indians could be subject to military discipline and

dedicated himself to this project of forming the troop. "Big

Red Nose"

as Casey was known, had little trouble in finding Cheyenne

willing to enlist. Artist Frederic Remington attested to the

success of

his efforts at training the troop. Just before the Sioux outbreak

of 1890, Remington had come to Fort Keogh along with General

Miles

who was in charge of a peace commission. Remington commented on

the Indians that Lieutenant Casey led by saying

that they "fill the eye of a military man until nothing is

lacking." p37

"Casey scouts,"

so named, in honor of Lieutenant Edward Wanton Casey, were the

end

of a long tradition of Indians assisting the Army at Fort Keogh.

While the Fort was still

a group of log huts, and the Sioux and Cheyenne ruled the

surrounding country, Crow

Indians were being enlisted for three month tours.216 Lieutenant

Edward W. Casey was

the first officer to drill the Crow scouts." p36

"Lieutenant M. C.

Martin related one story in 1889. Lieut Martin was sitting on the

MacQueen veranda (Hotel in Miles City)

yesterday, musing upon the condition of Indian affairs in the

west of body of Indians, said the Lieutenant, may be counted on

as played out.

Not only are the Indians becoming dwarfed into insignificance,

but they are experiencing the occasional domestic grievances of

civilization

and when that begins, savagery departs. It was only yesterday

that White Wolf, one of our Cheyenne scouts, came to me with his

countenance

expressing a mind deeply troubled and said: 'Heap hell!' 'What's

the matter?' I asked. 'Issue, you know Issue, like White Wolf,

is one of our scouts.' Then continuing, 'Issue,' said the Indian,

'he squaw she got mother; she come to camp--she talk much;

she make heap trouble with my squaw; I no stay in camp while she

stay.' 'Well,' I replied, 'you must tell her that if she don't

stop her talk

she must leave the camp, and you put her out if she don't stop.'

This seemed to please him greatly; he brightened up instantly

and said to me: 'you say, she not stop me put he out?' 'Yes' I

replied again. 'All right,' he answered, and he strode off in

direction

of the camp, apparently satisfied he had found a solution to the

difficulty.' 'No, Sir,' continued the Lieutenant; 'Indian

difficulties with the whites

are past and done for. When you see a mother-in-law come in among

a band of bucks and run the camp, it's an evidence

that all the fight has been taken out of them." p41-42

"Compensation given

to the Cheyenne soldiers was equivalent for the most part to that

given to other soldiers, twenty-five dollars

each month along with full Army issue. Enlisted Indians did not

have the same required length of service, their tour only lasting

six months. Housing for the Cheyenne soldiers was quite different

in that tents and tepees were used, rather than barracks.

Lieutenant Casey changed this by requesting funds and directing

the Cheyenne in logging operations. The Cheyenne soldiers were

constructing a cantonment of their own when the Pine Ridge

trouble started. These quarters, once construction was restarted,

were only occupied for a short time." p38

"While the Cheyenne

soldiers were located some distance south of the main garrison,

interpersonal conflicts between Whites and Indians still arose.

Lieutenant Casey felt it his duty to his troops to defend them

in these encounters and this he did. In one instance, Casey

reported to the commander that the son of Mrs. Foley,

the hospital matron cut off the braids of an Indian boy as he and

his mother passed the hospital on their way to the canteen store.

Casey pointed out what this act meant to the Indians and

mentioned other trouble that Mrs. Foley caused by letting her

cattle, horses,

and hogs have the run of the Post against orders. Casey hoped

that the commander would also consider the good service given by

the Indian boy's father, Scout Dog, and the feelings of all the

Indians under Casey's command when the commander decided

what action to take on this conflict." p38

"Supplying his

troops was another struggle that Lieutenant Casey had to face. On

May 7, 1890, he had to justify the amount of money

he requested for the construction of quarters for his troops. The

quarters that were built could not even compare with what

the rest of the Twenty-second Infantry stayed in. The Cheyenne

had little or no construction experience and the Department of

Dakota

wanted as much of their labor used as was possible. Casey and the

Cheyenne soldiers made do." p38

"Lieutenant Casey's

troops were outside the normal command and control of the

Twenty-second Infantry. As with the money matters

just mentioned, Casey corresponded with the Department of Dakota

through the commander of the District of

the Yellowstone. Orders for Casey would flow back through the

same channels. Authority to increase the size of his troop

was at the Secretary of War level, and a promotion selection

within his troop of noncommissioned officers was sent up to the

Department level. The Secretary of War set the size of Casey's

troop at one hundred. Rank structure of the unit was set at six

sergeants,

four corporals, two trumpeters and one teamster. Casey was

authorized to appoint them and the names were then sent to

the Department of Dakota." p38

|

--------- "Frederic Remington sketched

this member From the book By Ron Field, Osprey Publishing Ltd. 2003 ----- |

"A few Indian horse

stealing forays during 1889 foreshadowed the major Ghost Dance

trouble that hit the Northern Plains

in 1890 and concluded in 1891. A basic tenet of the Ghost Dance

belief was that a White man with scars on his hands and feet

would come among them. He would counsel them that the Indians

should use bow and arrow against the Whites

and that dead Indians would return to life and “the world

would roll over on the White men.”

This belief caused some Indians to start hostilities against

settlers. White Buffalo and Black Medicine were accused

of killing Mr. Furguson and after being located at Fort Keogh

were ordered arrested. This action excited the Indians at Lame

Deer

which in turn excited the citizens of the area. Nothing came of

this because troops under the command of Captain Mott Hooton

of the Twenty-second Infantry were sent, preventing any serious

conflict." p27

"Troops started to

move east in late November. Lieutenant Edward Wanton Casey took

his scouts to the area around Pine Ridge Dakota

on November 27, 1890. Orders were received by Captain H. H.

Ketchum about November 29, 1890 to move his company of

the Twenty-second Infantry to Fort Abraham Lincoln when

transportation was available. The people of Miles City did not

like the idea

that most of the troops at Fort Keogh were headed east, because

of their fears of Indian trouble in the Yellowstone valley,

but none really materialized. The element that had the most

eventful time in Dakota was Lieutenant Casey and his Cheyenne

scouts.

They first traveled to Belle Fourche, South Dakota and from there

headed for Hermosa via the railroad. At Hermosa they again

mounted their ponies and rode to Pine Ridge. The trip took from

December 7 to December 24, 1890. Different elements of Infantry

and Cavalry were being sent in various directions as Indians were

reported moving all over the region, but Lieutenant Casey

was in a difficult spot. Captain John A. Adams was ordered to

join Lieutenant Casey's scouts with his troops of the First

Cavalry.

Both Lieutenant Casey and Captain Adams were to join Colonel

Summers' camp while keeping an eye on Sitting Bull and his band

who were reported heading up Grand River and then south towards

Cheyenne River and Pine Ridge." p28

Lieutenant Casey's scouts

found it uncomfortably cold as they had packed no stoves but only

Sibley tents. This did not dampen

the spirit of Lieutenant Casey's Cheyenne scouts nor their

willingness to fight, as shown by Wolf Voice concerning the Sioux

position.

Frederic Remington in Pony Tracks quotes Wolf Voice stating the

following:

'De big guns he knock ''em rifle pit, den de calvary lum pas 'in

column

Injun no stop calavy-kill 'em heap but no stop 'em - den de

walk-a-heap

dey come too, and de Sioux dey go over de bluffs.' and with wild

enthusiasm he added, 'De Sioux dey go to hell!'

That prospect seemed to delight Mr. Wolf-Voice immensely."

p28

"Lieutenant Casey's

scouts did not understand that he was under orders not to fight.

This puzzled them because they were fired on,

but they held their ranks. All that Casey was doing was staying

off the Sioux's flanks and keeping General Miles informed of

their movements.

This task was not enough to make Casey believe that he was doing

all he could for peace. The day before he was killed,

some hostile forces were at his camp, and he was led to believe

that if he could but talk with the Indian leaders, the

hostilities could be

peacefully terminated. In his enthusiasm for peace, he went on

January 7, 1891 towards the hostile camp, accompanied by White

Moon,

one of his Cheyenne scouts. Bear-Lying-Down was sent by

Lieutenant Casey to inform Red Cloud that Casey was coming.

Bear-Lying-Down, accompanied by Pete Richards, a halfbreed,

returned from Red Cloud's camp to tell Casey not to advance

further as he was in danger

so near the hostile camp. Casey was found by these two messengers

in the company of his scout and two other Indians, Broken Arm,

an Oglala Sioux and Plenty Horses, a Brule Sioux. The message was

delivered and most of the party turned to mount their horses.

As Lieutenant Casey started to mount his horse, Plenty Horses

shot him in the back of his neck. Bear-Lying-Down rode to tell

Red Cloud.

White Moon and Pete Richards rode to General Brookes' camp and

the other two Sioux disappeared to their camp.

Brooke sent Lieutenant R. N. Getty, a subordinate of Casey, with

a detachment of his scouts after his body. They found the body

stripped

but not mutilated and recovered it. Casey's remains were sent

back east where he was buried on his family's estate.

Lieutenant Getty took charge of Casey's scouts and led them back

to Fort Keogh. At the trial of Plenty Horses, Captain Frank

Baldwin,

ordered to testify by General Miles, stated that Lieutenant Casey

had gone beyond his authority in asking to talk with the

hostile forces. Baldwin also stated that a state of war existed

and so Plenty Horses was acquitted. The reason for Plenty Horses'

action

was to regain respect among his people as he had been sent east

to the White man's school and felt that he no longer

was accepted in Indian society." p28-29

"A great deal of

Lieutenant Casey's time was spent in defending his troops. In

June 1890, he and other officers at Fort Keogh

retained a lawyer for some Cheyenne Indians who had been accused

of killing Mr. Furguson. In answer to a question

regarding his reasons for taking this action, Casey stated

something to the effect that having by special orders of the

Secretary of War

been placed in charge of the Indian recruits, of whom these four

Indians were a part, he felt it his duty to see that they

received

simple justice, nothing more. To insure that his troops were

protected against the winter weather, Casey requested that his

troops be dismissed

from Quarter Master duty in order that construction of their

quarters might be finished before it got real cold. He pointed

out

that with an interpreter, the planned class in packing would take

up a great deal of valuable time." p38-39

"With all the work

and training that had to be done, it was still hard to keep one

hundred men out of trouble. Casey's scouts had money

after pay day which could not all be spent at Fort Keogh, so

their officer had to deal with disturbances in town,

but the worst problem was AWOL (absent without leave). It was

hard to make soldiers from any group understand

that family contact had to be given up for some periods of time.

In the case of one Cheyenne soldier who went AWOL,

the family reaction was worth noting. One of Casey's men went

AWOL, in November of 1890, and when his parents

brought him back they said that he had disgraced his people. For

the disgrace that this soldier felt he later shot himself to

death." p39

"Later a major

turning point for Casey's scouts came during the Sioux trouble at

the Pine Ridge Agency when Casey was shot.

It was not only his troops that took his death hard, but most of

the Cheyenne nation felt the loss. On January 17, 1891,

the Yellowstone Journal reported that after they heard of Casey's

death, "the squaws were moaning and crying and the bucks

–

walked around with sullen faces. Casey's death and the end of

Indian hostilities marked the beginning of the end for the

Cheyenne

soldiers as a unit. The attitude of the

Cheyenne people towards military service changed, and where as

before parents would turn their sons in

after they had gone AWOL, later they would protect their sons

against capture. Recruiting became very hard as well

because a council of warriors was called when recruiters would

come to Lame Deer. These councils would tell the young men not to

go,

as it was 'heap bad medicine to be with the Whites.'" p39

"Lieutenant R. N.

Getty and Lieutenant F. C. Marshall were the officers that had to

preside over the decline of the Cheyenne soldiers.

On March 7, 1891, their return from Pine Ridge was reported. It

was a sad procession that Lieutenant Getty led into Fort Keogh

on that cold March day after the death of their leader and a hard

two months traveling. Getty probably saw the large task that

faced him.

He would have to fill Casey's shoes, and with the changing

attitudes among both Whites and Indians, his job

would be even harder than the one Casey had. In honor of what

Lieutenant E. W. Casey had done for, the Cheyenne soldiers,

Troop L of the Eighth Cavalry was renamed and officially became

known as 'Casey's scouts.'" p39

"A few years after

the death of Lieutenant Casey, Lieutenant F. C. Marshall replaced

Getty as commander of Casey's scouts.

It was pointed out in an interview with Lieutenant Sturgis given

by the Stock Growers Journal, January 14, 1893,

that Casey's scouts were still in top form. It also mentioned

that a statue would be erected at the Worlds Fair of a member of

Casey's scouts.

Although Casey's scouts were getting recognition in high places,

life around the garrison still had all the normal little

problems.

On April 28, 1894, the Stock Growers Journal reported on an

invasion of sorts of Casey's scouts' company area. The report

read:

The peace and dignity of the Indian company at Fort Keogh were

invaded by a tramp who took up quarters

in the immediate vicinity of theirs, and was so obnoxious that

Lieutenant Marshall assigned one of the sergeants, ( Lo )

whose knowledge of the English language is quite limited, to

invite the stranger to leave. Lo adjourned to his quarters,

buckled on

a belt full of cartridges, revolver and saber. Approaching the

visitor with all the military dignity he could command,

he spoke more forcibly than eloquent: 'Ugh! John; Go home G__

d___. 'Next instant the tramp was touching

only the high places on the prairie in his endeavor to reach the

railroad track." p40

"The days of

Cheyenne prisoners of war were not yet over at Fort Keogh, when

eleven of what were known as

"Casey scouts" were sent out in January 1892 to capture

Walks-in-the-Night and a few of his followers.

This mission was accomplished and he was held for trial at Fort

Keogh in the charge of L Troop, also known as "Casey

scouts."

In August 1897, Walks-in-the-Night escaped from "Casey

scouts." This brought to an end days when Fort Keogh

was a prison for some Indians and a home for others. "Casey

scouts" were disbanded a short time later." p36

"Casey's scouts had

one more mission of importance. During the unemployment problem

with the attending march on Washington, D.C.,

and the train takeover by the followers of Coxey, Troop L, Eighth

Cavalry was sent to Forsyth; this was one time

when Indian troops were used against Whites. The leadership of

Casey's scouts did not wane, nor did the soldiering ability of

the Cheyenne,

but the need for their services closed the book on a great

effort." p40

"In December of

1894, plans were made to disband Casey's scouts when their

enlistment ran out. For sentimental reasons

the breakup was very sad for soldier and civilian alike, as many

friendships had been formed. On May 4,1895,

twenty-seven Cheyenne were discharged and a month later the troop

was skeletonized.

Lieutenant Marshall turned in all the property and the officers

were sent to Fort Meade, South Dakota." p40

" Figure 3. Members of Company G,

Twenty-second Infantry taken probably in 1892 or 1893.

Note the small variance in the wearing of the uniform, three

different types of hats, some with

brass. Some coats were open, and one soldier is wearing an old

buffalo coat. (Courtesy of

Christian Barthelmess collection, Montana Historical Society.)

"

Photo from:

FORT KEOGH: CUTTING EDGE OF A CULTURE

By

Josef James Warhank

(Ed., note that the Soldiers in the

above photo are still armed with the Model 1873 .45-70

"Trapdoor" Springfield rifles.

The following excerpts deal with marksmanship at Fort

Keogh. )

"Various Army

weapons were used at Fort Keogh during the life of more than

thirty years. Every soldier had some contact with a rifle,

and of necessity this piece of equipment played a large role in

the daily life at the Post. The primary rifle in use at Fort

Keogh

from its beginning until 1893 was the Springfield. Standard

length this weapon was 41.313 inches for those built between 1873

and 1888.

Barrel length was 21.875 inches. A walnut stock was used and the

gross rifle's weight was about seven pounds. Empty casings would

often stick

in the chamber after firing, but the rifle was accurate at up to

900 yards. The soldiers at Fort Keogh during hard times reloaded

used cartridges, as was done at other posts in an effort to save

money. The Springfield was discontinued in 1893 and replaced

with the bolt-action Krag-Springfield .30/40 rifle. If a soldier

lost the Springfield model in 1877, he had to pay $16.25,

and this rose as different models were introduced." p73

Model 1873 Springfield rifle

"While the troops

were campaigning, very little rifle practice was required. In

March 1885 about 2,000 rounds were fired in practice.

The following month about 9,000 rounds were fired and about 2,000

per month for the months that followed. In 1890

Company H, Twenty-second Infantry fired 15,000 rounds during

their practice season. This reflected the Army's ever increasing

interest

in target practice. The companies were rotated to the range about

one per month and the results were reported to the

commander." p73

"When the

Twenty-second Infantry replaced the Fifth Infantry at Fort Keogh,

the emphasis changed from who won the department competition

to where it would be held. Colonel Swaine asked for studies of

costs to improve the Fort Keogh range and

the local press started to count the money that the City would

make from all the visitors. Fort Keogh, with the Twenty-second

Infantry,

lost both the competition and the bid to hold it at the

Post." p94

"Interest in

marksmanship did not wane at the Post in spite of losses.

The Miles City team accepted a challenge from officers at Keogh

in 1891, and during the same month of August, the Department

Cavalry

competition was held making the Post and the city both busy

places. The next year the Department Rifle matches were moved

from Fort Snelling to Fort Keogh. In 1893 not only were the

matches held at Keogh, but Sergeant Chapias of Company A,

Twenty-second Infantry won the gold medal and left for Chicago

and the Division competition." p94

(Ed., Desertions did not seem to be as

big a problem at Fort Keogh as they were at other frontier posts,

but the harsh and rough existence of Soldiers on the frontier did

give some cause to desert.)

"Private Edward

Murray of Captain Thorne's Company C, Twenty-second Infantry, had

a drinking problem that led to his reduction in rank

and subsequent indebtedness to other soldiers. Murray escaped.

Private Edwin Berry of the same company was said to have been a

tramp

before he entered and wished to continue in that life style.

Berry used a great deal of vulgar and obscene language and was

not missed

by his fellow soldiers. Captains Hooton and S. W. Fountain did

not attempt, much understanding of the men

which deserted from their companies. Hooton wrote of two

deserters; both were '... worthless, drunkards and the kind of

recruits

that might be expected from a great city.' Fountain described

deserter Martin Kristensen as a '... lazy worthless man.'

Fountain went on to say that he had never been anywhere that an

enlisted man could serve with less reason for complaint than at

Fort Keogh." p78

(Ed., The following passages deal with duties and examples of everyday life and society at the Fort.)

"An example of

delivery duty was the case of Lieutenant E. W. Casey's horse.

Sergeant Christian Barthelmess a member

of the Twenty-second Infantry band was assigned to deliver to

Miss Sophia Swaine, the daughter of Colonel Swaine,

a horse from Casey's estate (see figure 3, Barthelmess photo of

the Twenty-second Infantry). Sophia Swaine, who lived in

California,

had counted Casey among her suitors and after the Lieutenant

died, Colonel Swaine bought her his horse." p85

"The Twenty-second

Infantry band, which followed that of the Fifth Infantry, was

said to be just as good and gave of their talent

just as much. Equipment of the Twenty-second Infantry band

included such instruments as the cornet, bass, alto horn, French

horn,

clarinet, piccolo, baritone, trombone, tambourine and both the

bass and snare drum. In addition to playing an important official

function,

the band was the main form of entertainment at the Post for its

entire existence." p87

"Although some

causes of mental illness were vaguely understood, the treatment

varied greatly. While the Fifth Infantry

was at the Post, a mentally ill soldier would be confined to the

hospital, and if no improvement came he would be shipped east.

In the case of Private Frank Fitzsimmons, the Twenty-second

Infantry had to take a different approach. Fitzsimmons, a

well-known

ballplayer in the area of the Post, went insane and because of

his violence was put in the guardhouse, since the hospital could

not control him. While there waiting to go to a government insane

asylum, Fitzsimmons gouged out both of his eyes with his right

thumb;

one eye ball landed on the floor and the other hung from the

socket. Fortunately, according to Dr. Harvey, the

insanity suffered by Fitzsimmons was of a character that the

brain was not susceptible to sensing of physical pain.

After a few months, in August 1889, Dr. Harvey sent Fitzsimmons

to St. Paul, Minnesota. He was still bedridden, and was chained

down

to the bed with his feet bound together and four-ounce boxing

gloves were placed on his hands." p100

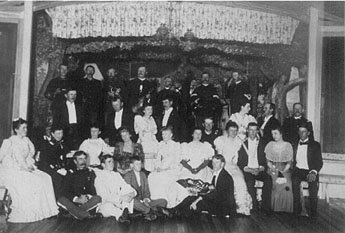

Fort Keogh, Montana, July 12, 1893.

Post Hall, audience and

members of the 22nd Infantry band. Christian Barthelmess,

photographer.

PAc 95-68.B-278.

Montana Historical Society http://www.his.state.mt.us/research/photo/barthol.html

"When the

Twenty-second Infantry replaced the Fifth Infantry at Fort Keogh,

it was reported that most of the young officers

were not married. Some would find out how easy it was to get

married at a large post like Fort Keogh, as the case of

Lieutenant

Alvin H. Sydenham illustrates. The Lieutenant received a

"Dear John" letter from his fiancée six months after

he graduated from West Point.

Five months after he got the letter he married the sister of

Lieutenant Joseph A. Gaston at Fort Keogh." p102

"In the second part

of the decade of 1880 some citizens of Miles City felt that there

was profit in ambushing soldiers as they returned

to Fort Keogh. Usually the robbers were out of luck, because the

soldiers had little money but on a few occasions money was taken

or

the soldiers badly beaten. Most of the attacks took place at the

west end of the railroad bridge.

Three years after this first rash of attacks in 1889, assaults

were in the news again. They became so bad that Colonel Swaine

of the Twenty-second Infantry directed that all suspicious

looking characters on the reservation be arrested. Those seized

were

brought before an officer and examined for specific charges. This

strictly enforced policy was quickly effective." p112-113

"Almost the entire

garrison left the Post for a practice march in 1888 and 1889. In

1888 only two troops of the Eighth Cavalry

stayed at the Post. Even the hospital staff joined in this six

day, sixty-mile march. The next year two troops and eight

companies left the Post

toward the little Missouri. Grain for the horses was deposited

three days march apart, as logistical support was also being

tested.

These long marches became an annual occurrence, as in April 1890

the entire infantry command numbering five hundred men

covered the area west of the Tongue River." p89

"The soldiers during

these training marches covered various military subjects. The

Keogh soldiers were instructed in pitching camp,

outpost duty, camping in enemy territory, attack and defense

convoying, hasty entrenchment and breaking camp.

Although these subjects were closely related to combat, the band

was still sent to the field with the other troops." p90

"War games were a

prominent part of the 1889 practice march. While the troops were

on the little Missouri, Lieutenant Wainwright

reported to the local press that after some drilling, the

soldiers went into the hills and maneuvered to apply in practice

what they had learned. Some live fire was used as troops from

Forts Keogh, Custer, and Meade joined in mock battles,

while for nearly a month only one company of men remained at

Keogh." p90

"After returning to

garrison, drill also awaited the troops, but by 1889 it had been

cut down from the two hours a day

that General Terry had previously ordered. If a person would have

stopped at Fort Keogh on any given day during its active years,

the one thing he or she would be sure to have seen was drill

being conducted. On special occasions it was full dressed

drill." p91

Captain John G. Ballance |

"Orders

were received at Fort Keogh on July 13, 1892, |

"A national movement

soon required more help from the soldiers at Fort

Keogh........................Unemployment was high

across the nation in 1894 and the miners of Montana were

affected. A militant group of miners under the leadership of

William Hogan

was formed as part of a national movement. The national

organization was started in Ohio by a man named Jacob S. Coxey.

It was planned that Coxey's 'Army,' as it was called, would meet

in Washington, D.C. in 1894. The Montana element

of the Coxeyites was more militant than most and because of this,

the U.S. Army was needed to maintain order and the

troops of Fort Keogh were given the mission. Governor John E.

Richards called on President Cleveland for help

after the Coxeyites under Hogan seized a train in their effort to

reach Washington. On April 25, 1894, troops left Fort Keogh via

rail

for Forsythe, Montana to arrest Hogan's followers when they

arrived at that place. Some of the Coxeyites headed for the hills

when they faced United States troops, but most were arrested. The

troops were then ordered to escort the prisoners to Helena.

Companies A, C, and H of the Twenty-second Infantry moved the

prisoners to Helena and guarded them at the fairgrounds

until civil authority could manage and on July 27, 1894 Major E.

H. Liscum, who commanded the Battalion

returned with his men to Fort Keogh." p30-31

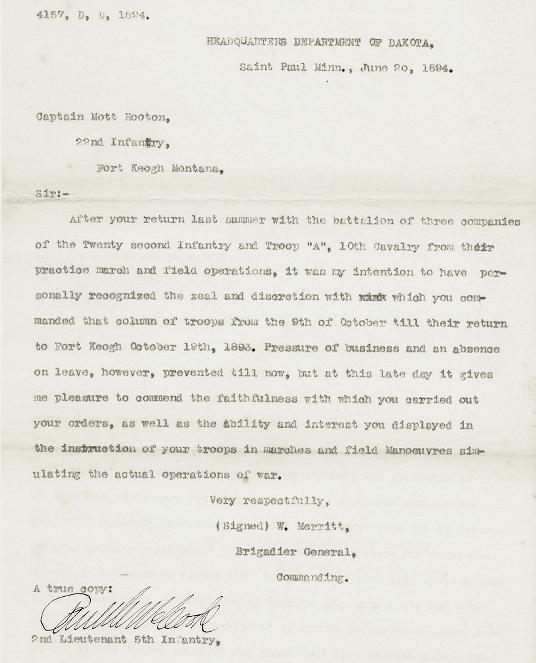

A rather late letter from Brig. General

Wesley Merritt, Commander of the Department of the Dakotas,

to Captain Mott Hooton of the 22nd Infantry, congratulating CPT

Hooton on his leadership in October of 1893,

of a Battalion consisting of three companies of the 22nd Infantry

and Troop A of the 10th Cavalry.

The 10th Cavalry (Buffalo Soldiers) would again serve alongside

the 22nd Infantry in the twentieth century

in Vietnam, and in the twenty-first century in Iraq.

German Singing Society, 22nd Infantry,

Ft. Keogh, May 13, 1894

The conductor, in the white trousers, is Christian Barthelmess

Photo - National Archives 111-SC-9 7983

**********************

Anyone wishing to learn

further about the history of Fort Keogh is highly encouraged

to read Josef James Warhank's entire work:

Fort Keogh: Cutting Edge of a Culture

To view the entire thesis, click on the following USDA banner, or use any of the links below.

Diona Austill Program Support Asst. USDA-ARS Fort Keogh LARRL 243 Fort Keogh Road Miles City, MT 59301 Phone: 406-874-8219 Fax: 406-874-8289 Email: diona.austill@ars.usda.gov

United States Department of Agriculture - Agricultural Research Service Miles City, Montana

http://www.ars.usda.gov/Main/docs.htm?docid=6395

www.ars.usda.gov/npa/ftkeogh/history

USDA, ARS Fort Keogh

Livestock and Range Research Laboratory

243 Fort Keogh Rd., Miles City, MT 59301-4016

Phone: 406-874-8200, Fax: 406-874-8289

Home | Photos | Battles & History | Current |

Rosters & Reports | Medal of Honor | Killed

in Action |

Personnel Locator | Commanders | Station

List | Campaigns |

Honors | Insignia & Memorabilia | 4-42

Artillery | Taps |

What's New | Editorial | Links |