![]() 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry

1st Battalion 22nd Infantry ![]()

The Datu Ali Expedition -1905

![]()

Campaign Streamer awarded to the 22nd Infantry for its service in Mindanao 1904-1905

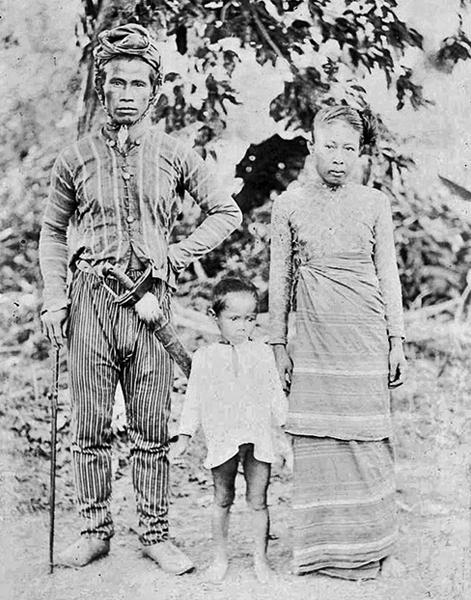

Datu Ali, brandishing his kris most prominently, in a portrait with one of his wives and son.

Photo courtesy of the website:

MOROLAND

The History of Uncle Sam and the Moros

1899-1920

Datu* Ali was the last, and most

formidable Moro chieftain to oppose American rule

on the island of Mindanao. For nearly two years, operations

against Ali were carried out by

several formations of the US Army and the Philippine

Constabulary.

* The word "Datu" was

used to describe leading members of Moro royalty. The Sultan was

the highest authority in Moro society, followed by the Datu's.

Depending upon what level

of prestige an individual Datu occupied, the word could be

translated to mean prince,

duke, count or baron. Period spellings of the title included

"Datuk", "Dato" and "Datto".

Ali eluded capture until finally

surprised and killed by a Provisional Company of the 22nd

Infantry

led by Captain Frank R. McCoy, the Aide De Camp of General

Leonard Wood.

Colonel John White, who spent 15

years as an officer in the Philippine Constabulary,

sets the stage with a description of Ali's home land -- the

Cotabato District of Mindanao:

EARLY in June, 1904, General

Wood called upon Colonel Harbord to organize a Constabulary in

the District of Cotabato,

the largest and perhaps least-known division on the Moro

Province, where a prominent Moro chief named Datu Ali

had recently started on the war-path. Colonel Harbord relieved me

as adjutant for assignment as Senior Inspector of the

Constabulary

of Cotabato with instructions to recruit as rapidly as possible

among the tribes of friendly Moros and organize a force that

could be used as Scouts,

accompanying expeditions of United States troops against the

hostiles scattered throughout the length and breadth of the

valley of the

Rio Grande de Mindanao. Cotabato District consisted of the valley

of this broad, deep, muddy stream, a valley some two hundred

miles long

and from ten to fifty broad. This watershed contained large areas

of swamp and lakes, with villages of Maguindanaw Moros sparsely

scattered

along the banks of the river and its tributaries or amid the

almost trackless and impassable swamps. Back of the valley rose

forbidding ranges

of mountains, culminating in Mount Apo, eleven thousand feet in

height. In the jungles of these mountains were legendary pagan

tribes,

rejoicing in the names of Tirurayes, Manobos, Bagobos, Bilanes,

and many more such.

The Maguindanaws were the

largest tribe of Moros. They controlled practically the whole of

the mainland of Mindanao.

Although more agricultural and less piratical than their cousins

in Sulu, they held almost as tightly to their ancient privileges

of slavery

and control of the pagan tribes, while the situation of their

bamboo villages and earthen cottas (forts) on the shores of the

mountain lakes,

as in Lanao, or amid the swamps, as in Cotabato, made campaigning

against those chiefs who refused to recognize the authority

of the United States both difficult and costly.

The Spaniards had sent many an

expedition up the Rio Grande, and with shallow-draft gunboats had

shot their way into the heart

of Cotabato District. They obtained concessions from Datu Utu,

the Maguindanaw chief who then ruled that swampy land. But the

control

exercised by the Spaniards extended little if any further than

the range of cannon shot from the toy men-of-war, while the price

they paid in men

and blood for even such victory was heavy. Furthermore, every

inch of ground wrested from the Maguindanaws must be controlled

by stone-fort

or blockhouse. When, in 1899, the Spaniards withdrew before the

advancing Americans from the north, anarchy reigned in Cotabato.

Datu Utu had gone to the voluptuous reward of good fighting

Moros, and his nephew, Datu Ali, ruled in his stead. ¹

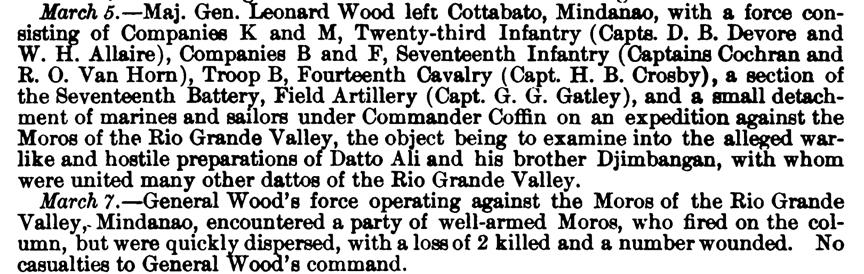

The Annual report to the War

Department for 1904 included the following passage which

specifically mentioned

Datu Ali and related the difficulties associated with a Moro

chieftain like him:

In the upper Cottabato Valley,

Dato Ali is out with a small following. Ali has always been a bad

character, a gambler, a slave dealer, and has declared

that he will not obey the law, especially the slave law. He and

his brother, Djimbangan were the principal leaders in the sack of

Cottabato in 1899.

As long as he was not interfered with in his slave trade and

oppressing others he was apparently friendly, but as soon as

steps were taken to bring to an end

the revolting conditions existing in his section, he broke out in

armed defiance of authority, collected about 3,000 followers, and

constructed at Serenaya a large fort, etc.

In March these forces were defeated and the works destroyed, and

Ali, with a few followers, went into the up-river country, where

he is at this time. Eighty-five pieces

of ordnance were taken from the Serenaya fort, 21 of them large

cannon from 5 ½ - 3 inches caliber. In May he ambushed F

Company, Seventeenth Infantry,

with disastrous results to the company and considerable loss to

himself.

All's party is the only outfit of Moros now openly hostile and it is being vigorously followed by troops and scouts.

The country he is operating in

is of the most difficult description, consisting of lakes,

rivers, and immense swamps, covered with tropical vegetation.

There is little

solid ground; trails are muddy and difficult and bordered by

grass from 10 to 15 feet high—everything combines against

the pursuit. It is not believed that there will be

in future any very serious resistance to authority on the part of

Moros, but there will be constant work of a police character,

which will require the use of troops and constabulary.

The Moro chiefs do not like our occupation of their country,

because it means an end of the disgustingly brutal exercise of

authority which characterizes their conduct of affairs.

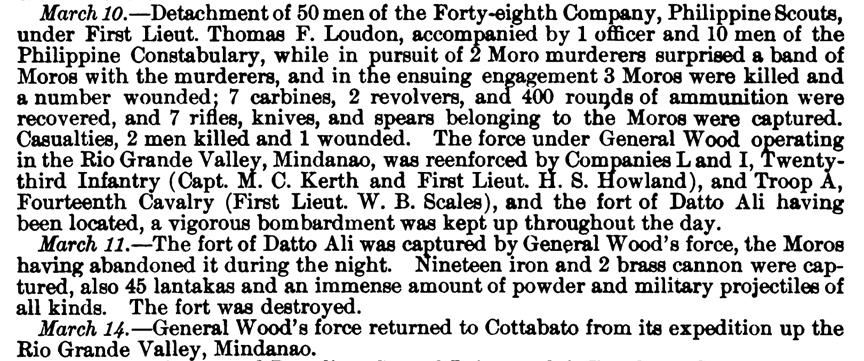

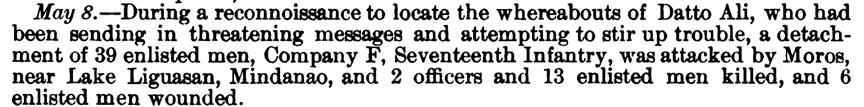

The following passages

illustrate the problems the US Army was having with Datu Ali.

They are taken from the Annual Reports to the War Department, and

indicate encounters

with Ali during the year 1904:

In his report to the War

Department for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1905 Major General

Leonard Wood,

Commander of the Department of Mindanao in the Philippines summed

up the problem of Datu Ali:

Dato Ali is in hiding with a

small following somewhere in the interior of the island of

Mindanao, east of Lake Liguasan. He has been quiet and has

committed

no hostile act since last October, and his people to the number

of fifteen to twenty thousand have come in, settled along the Rio

Grande, and gone to work.

Conditions among the remaining non-Christians have continued

favorable, and great progress has been made in establishing

friendly relations with them and

in putting into operation a simple system of control through

their headmen. The Moro outbreaks are largely due to the actions

of fanatical Arab priests, of a

class which is a disturbing element throughout the East. These

difficulties and disturbances are growing less frequent and less

dangerous, as, in every instance,

failure and heavy losses to the Moros have been the result, and,

while occasional troubles may be expected, they will occur less

and less frequently,

and will be easily handled.

The following is the short, but

official narrative of the operation which put an end to Ali's

activities,

as recorded by CPT Daniel Appleton, in the 1922 Regimental

History.

The Datu Ali Expedition

Just as the regiment had completed preparations

for the return to the United States, and the officers and men

were beginning to anticipate

the joy of being once more in their native land, affairs took a

sudden turn in the other direction, and the following order,

quoted in full

on account of its intense interest, again placed the regiment in

line for further active service in the Philippines.

HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT

OF MINDANAO, Zamboanga, Mindanao, P. I.,

October 5, 1905. Strictly Confidential.

The Department commander

is preparing an expedition to surprise and capture Datu Ali. In

view of the excellent service

and experience of the 22nd Infantry, he has selected it to

furnish the major portion of the expedition, which will be

commanded

by Captain F. R. McCoy, A. D. C., he being the only officer in

the department who has been over the route decided on.

He directs that for this hard and important work, one first

lieutenant, two second lieutenants and one hundred picked men be

selected

as were those forming the original provisional company, armed and

equipped as at the end of their tour in the Rio Grande valley,

and be prepared to board the Sabah on the morning of the 13th

inst, at Camp Overton. The necessary medical attendance and

supplies

will be furnished, the supplies to be put in packages not

exceeding forty pounds. One hundred rounds of extra rifle

ammunition (1,903) per man,

and forty rounds of pistol ammunition will be taken. Field and

travel rations will be prepared for you at Camp Overton or

Zamboanga.

Squad boxes with extra clothing, etc., may be taken aboard ship

to leave at base.

Bring, if possible, one

hundred picked cargadores; if not, wire deficiency and it will be

made up here. Tomas Torres,

civil interpreter, will accompany. The destination of these

troops, further than Camp Overton, will not be made known

to even the officers with them. Acknowledge receipt by wire.

Very respectfully,

DANIEL, H. BRUSH, Lieut. Colonel, Inspector General,

Acting Military Secretary.

In accordance with this confidential

memorandum, a provisional company of the 22nd Infantry was again

organized on October 9, 1905.

Following are the names of the officers assigned to this company:

First Lieutenant Solomon B. West, Commanding.

Second Lieutenant Philip Remington.

Second Lieutenant B. B. McCroskey.

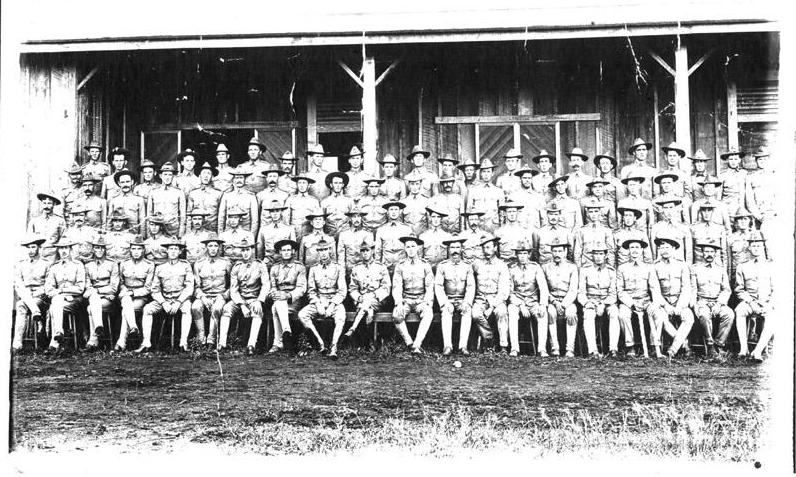

The Provisional Company of the 22nd Infantry formed for the Datu Ali expedition

Photo courtesy of Robert Hart whose father

Grover Hart was a member of the Provisional Company.

Private Hart is in the front row, fourth from the left.

|

Two soldiers identified

from the above photo of the Left, Private Grover Hart Company G Right, 2nd Lieutenant Benjamin

B. McCroskey |

|

The provisional company left Camp Keithley at

4:30 p. M., October 11, 1905. At this time nothing definite was

known of Datu Ali's whereabouts,

though he was generally thought to be on his ranchiera on the

Malola river.

In order to avoid any possibility of encountering Ali's spies,

the expedition proceeded to Digas, on the gulf of Davao, landing

at Digas on October 16.

At this point a detachment of ten Filipino scouts, under

Lieutenant Henry Rogers, P. S., joined the Americans; and before

proceeding further,

all footsore and sick men were weeded out and left behind.

On the morning of October 22 the advance guard

of the column, under Lieutenant Remington, reached Datu Ali's

ranchiera. The main body,

under Lieutenant McCoy, followed along closely, while flank

patrols were sent out under West and Johnson.

Perceiving Datu Ali on the porch of his house, with some ten or

twelve of his followers, Lieutenant Remington with the advance

guard of two squads,

rushed forward, hoping to capture the unarmed party by a complete

surprise. However, the movements of Remington's men were quickly

discovered,

and the enemy disappeared inside the house, Datu Ali, himself,

firing point blank at Lieutenant Remington as the latter reached

the entrance.

The shot missed Remington, but killed Private L. W. Bobbs,

Company G, 22nd Infantry. At almost the same instant Lieutenant

Remington

returned the fire from his pistol, shooting the Datu through the

body and bringing him to his knees. Struggling to his feet the

Datu made a desperate effort

to escape, but was shot dead by the men of the advance guard, two

of whom were wounded in the course of the fight.

Private Morton L. Bales, Company K, subsequently died of his

wounds, and Private John J. Rorke, of Company G, was less

seriously wounded. §

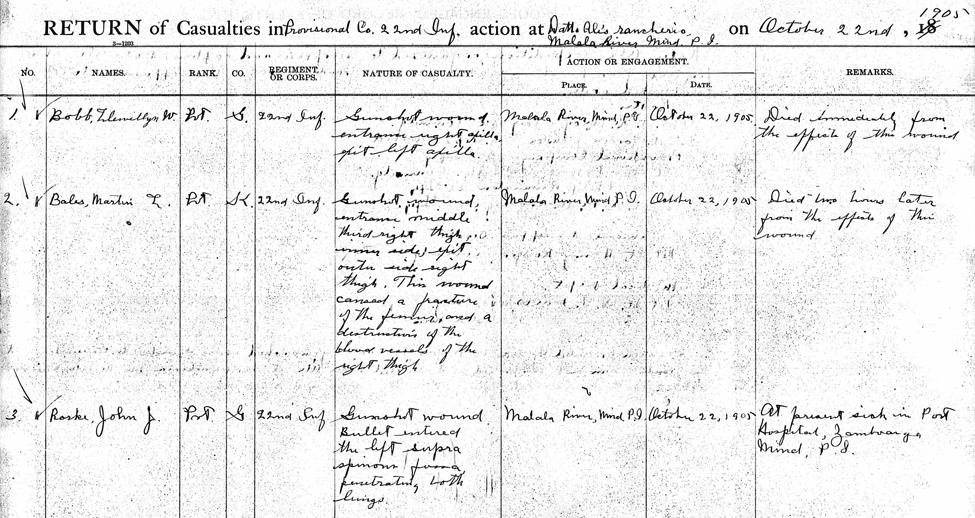

§ ( Website editor: The names of the 22nd Infantry soldiers who died were mis-spelled in the Regimental history. Those soldiers were:

Private Llewellyn W. B. Bobb of Company G 22nd

Infantry

Private Martin L. Bales of Company K 22nd Infantry

Private John J. Rorke was noted in the

Regimental history as being "less seriously wounded"

however, as seen in the Casualty Report

posted below on this page the bullet which struck Rorke entered

his upper back and penetrated both of his lungs. It is not likely

that

Rorke returned to full duty as he was dicharged some eight months

later on account of disability.)

Above: The casualty report filed by Captain Frank McCoy

indicating the casualties of the Provisional Company of the 22nd

Infantry

in the fight at Datu Ali's rancheria.

Private John J. Rorke of Company G

listed on Line 3 in the above report was born in Lockport,

Niagara County, New York

in August 1882. He enlisted in the Army as a Private for a period

of 3 years on January 6, 1905 at Chicago, Illinois. His

enlistment

record indicated he stood 5 feet 5 ½ inches tall, had light

brown hair, blue eyes and a fair complexion. His previous

occupation was

listed as Laborer. He was assigned to and joined Company G 22nd

Infantry on March 10, 1905 at Camp Keithley on the Island of

Mindanao in the Philippines. The casualty report states that on

October 22, 1905 Private Rorke suffered a "Gunshot

wound. Bullet

entered the left supra spinous fossa penetrating both lungs."

He was admitted to the Post Hospital at Zamboanga on the Island

of

Mindanao. Rorke was discharged for disability in the line of duty

on July 20, 1906 while at the General Hospital at the Presidio

at San Francisco, California with a character reference of Good

and a notation of "service honest and

faithful." He was cited for

"bravery in action, in voluntarily

continuing in the fight after being severely wounded in both

lungs in engagement with Datu Ali"

in General Orders No. 43 Department of Mindanao December 31,

1905.

Private Martin L. Bales of Company K

listed on Line 2 in the above report was born in Annville,

Jackson County, Kentucky in January 1881.

He enlisted in the Army as a Private for a period of 3 years on

April 5, 1902 at Wichita, Kansas. His enlistment record indicated

he stood

5 feet 6 inches tall, had black hair, brown eyes and a ruddy

complexion. His previous occupation was listed as Farmer. Bales

served in

the 28th Field Artillery Company and was discharged from this

enlistment by General Order on December 15, 1904 at Fort

Leavenworth,

Kansas as a Private with a character reference of Excellent.

Bales re-enlisted in the Army on December 27, 1904 at Shawnee,

Oklahoma

Territory. On this enlistment his previous occupation was listed

as Soldier. He was assigned to and joined Company G 22nd Infantry

on March 10, 1905 at Camp Keithley on the Island of Mindanao in

the Philippines. The casualty report states that on October 22,

1905

Private Bales suffered a "Gunshot

wound, entrance middle third right thigh, inner side, exit outer

side right thigh. This wound caused a

fracture of the femur and a destruction of the blood vessels of

the right thigh." The report also

indicates that he "Died two hours later

from the effects of this wound."

|

Left: Private Llewellyn Winfield Bobb listed on Line 1 in the above report. Killed by Datu Ali on October

22, 1905 when Ali fired his rifle at Lieutenant Philip

Remington According to his enlistment

record Llewellyn W. Bobb was born in Richland County,

Wisconsin The casualty report states that

on October 22, 1905 Private Bobb suffered a "Gunshot

wound Private Bobb was buried in the

Post Cemetery at Camp Keithley and on July 14, 1906 his

remains Photo by orbweb49 from Ancestry.com |

This second provisional company of the regiment

acquitted itself as splendidly as had the first, accomplishing

its mission in the quickest time

and with the minimum loss of life, and unquestionably added

another lustrous page to the regiment's history. Following the

action

recommendations were submitted for the award of a certificate of

merit to Sergeant, First Class, J. C. Gunn, Hospital Corps;

Sergeant Louis A. Carr, Company K, Corporal Barry Smith, Company

G, and Private William B. Hutchinson, Company K, all of the 22nd

Infantry.

November 3, 1905, the provisional company

returned to Camp Keithley and was disbanded.

At this point the active service of the 22nd Infantry in the

Philippines came to an end; the regiment engaged in no further

field service,

and spent the following month in making extensive repairs to some

Spanish gunboats which had sunk, and in consequence had first to

be raised.

This in itself constituted an engineering project of considerable

proportions.

The 22nd Infantry left Manila for the United

States via Nagasaki on December 15, 1905, and arrived at San

Francisco,

January 14, 1906, after an uneventful voyage on the transport Sherman.

|

Captain Frank R. McCoy Personal Aide De Camp Photo taken 6 years after the Ali

expedition Left: A letter from Letter courtesy of Robert A. Fulton, MOROLAND The History of Uncle Sam Tumalo Creek Press, Bend, Oregon 2007, 2009 ISBN 978-0-9795173-0-3 |

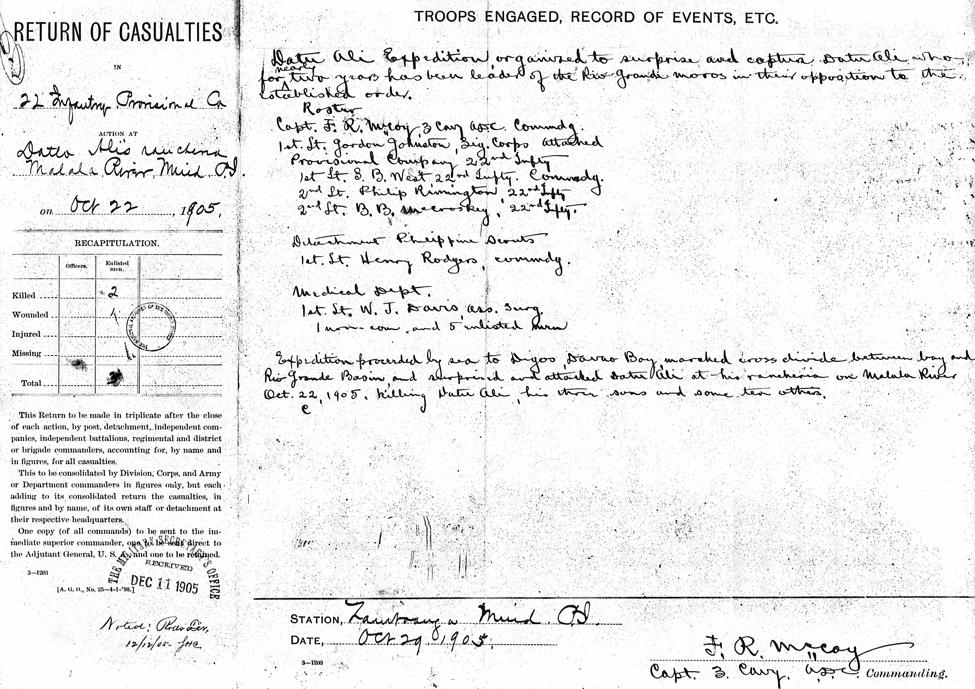

Above: The casualty report of the Datu Ali expedition filed by

Captain Frank McCoy giving a summary of the operation.

A week after Ali was killed the event made the US newspapers:

|

Left and above: article from |

|

Left and above: article from |

The following interesting

account of the Datu Ali expedition was published in the

Army And Navy Register January 6, 1906:

DEATH OF DATTO ALI

[The true story of the pursuit, capture and death of the notorious Moro outlaw told by a member of the 22d Infantry and published in the Philippines Gossip.]

Datto Ali, or rather "Datu

Ali," as he was known among his people, was a mere nobody a

few years ago. Being a great gambler, and a natural cutthroat,

he watched and waited for his opportunity to force himself

forward and become a leader of his people. The enactment of the

anti-slavery law in the

Moro province gave him the chance he was looking for. Gathering

about him the scum and riff-raft of the Cottabato Valley he

organized a gang of outlaws

and murderers, who caused the government considerable trouble and

annoyance until recently, when he met his death at the hands of

Lieutenant Philip Remington

of the 22d Infantry, while the latter was leading a charge

against the notorious outlaw.

Up to October General Wood had

made many attempts to locate and capture this robber chieftain.

He has had several scrimmages with the American troops,

but Invariably managed to elude capture and death.

When the anti-slavery law was

passed, Datu Ali seized upon it as an excellent means for

exciting the people, and many more Moros flocked to his standard,

believing him to be a "Heaven-sent leader."

The real causes leading to the

last and finally successful expedition against Datu Ali were

mainly the fact that the constabulary operating against him

were unable to successfully prevent his depredations, and a

letter was written under date of October 2, 1905, by Captain

George T. Langhorne,

11th cavalry, secretary of the Moro province and acting governor

during the temporary absence of General Leonard Wood, to

Brigadier General James A. Buchanan,

commanding the department of Mindanao, in which he said:

"Datto All has lately

commenced raidlng the friendly Moros on the Rio Grande,

Cottabato. It Is impossible for the constabulary force in control

of the province

to successfully prevent his depredations; therefore, I have the

honor to request that such steps as you may think necessary be

taken in order to capture

and destroy Ali and the band of desperadoes which follow

him."

Three days after the receipt of

this letter at the department headquarters. General Buchanan sent

the following Instructions to Major Crittenden,

then in command of the troops at Camp Kelthley:

"The department commander

is preparing an expedition to surprise and capture Datto Ali. In

view of the excellent service and experience of the 22d Infantry,

he has selected it to furnish the major part of the expedition

which will be commanded by Captain Frank R. McCoy, A. D. C., he

being

the only officer in the department who has been over the route

decided on.

"He directs that for this

hard and important work one first lieutenant, two second

lieutenants and one hundred picked men be selected, as were those

forming

the original provisional company, armed and equipped as at the

end of their tour in the Rio Grande Valley, and be prepared to

board the 'Sabah' at

Camp Overton on the morning of the 13th instant.

"The necessary medical

attendance and supplies will be furnished. One hundred rounds

extra rifle ammunition and forty rounds extra revolver ammunition

will be taken per man.

"The destination of these troops further than Camp Overton will not be made known to even the officers with them."

At the same time General

Buchanan wired the commanding officer of the troops at Camp

Overton to make every arrangement for rations, supplies, etc.,

so as not to delay the troops.

Other than the general himself,

Major Crittenden and Captain McCoy, there was not a soul, either

among the troops or the Moros who had the faintest idea

of what the expedition was for. Even Datu Ali considered himself

safe, as word was always brought him by swift runners of every

expedition against him.

All plans, arrangements, etc.,

for the capture of All were placed in the hands of Captain Frank

R. McCoy, a youthful but able officer, aide-de-camp

to Major General Leonard Wood. He was given full power and

selected his forces with the greatest care. He had with him 1st

Lieutenant Gordon Johnson,

signal corps, as field quartermaster and commissary; 1st

Lieutenant Wilson T. Davis, assistant surgeon, as the surgeon, a

young medical officer who

has made an enviable record for himself at Corregidor Island,

while in charge of the tuberculosis ward; arid a provisional

company of the 22d Infantry,

consisting of 1st Lieutenant S. B. West, and 2d Lieutenants

Philip Remington and B. B. McCroskey; a detachment of the

Philippine scouts under

1st Lieutenant Henry Rodgers, several hospital corps men, one

interpreter, Datto Enok, as guide, Stevedore Clement and 186

cargadores.

Captain McCoy realized that for

the past two years several unsuccessful attempts had been made to

capture Datu Ali, and knew that if he attempted

to go by way of the Cottabato Valley he could not succeed, as

every movement of troops in that region was at once made known to

him by spies.

Datu Ali's hiding place was

supposed to be somewhere in the Lake Liguasan region. Captain

McCoy knew of but one trail by which he might reach the

Moro outlaw, and that was the trail from Digos, on the Gulf of

Davao, through the Bagobo and Bilan country, to Buluan. As there

were no Moros living

on that trail and as the Hill men in that region were more afraid

of Ali than of the Americans, the department commander thought

that trail the only medium

through which to affect a surprise.

The department commander,

General Buchanan, conferred with Captain McCoy and enjoined the

strictest kind of secrecy in all that pertained to this

expedition,

as the sole hope of capturing Ali was through his (Ali's)

ignorance of the move.

Therefore, at the suggestion of

General Buchanan, Captain McCoy, at that time acting as chief

quartermaster of the department, openly proceeded to the

Cottabato Valley, apparently in his capacity as chief

quartermaster, and excited no suspicion among the Moros. While in

the Cottabato Valley he obtained

some very valuable information, which, unlike the information

usually obtained from the Moros, was accurate and correct.

Datto Piang, the Sheriff Afdal

and Datto Enok, all friendly to the Americans, divulged the

information that owing to sickness in the family of Datu Ali,

the Moro chief had left his hiding place in the Lake Liguasan

country and had settled with a personal body-guard at his

rancheria, which was reported

to be located somewhere (vague, but we made it do) on the Malala

River.

Accordingly, the one hundred

picked men and the three officers of the 22d infantry left Camp

Keithley on October 11 and boarded the chartered transport

Sabah making for Zamboanga, where they arrived the following

night, picking up Captain McCoy, Lieutenant Davis, the surgeon

and Lieutenant Johnson,

when the entire expedition proceeded to Digos on the Gulf of

Davao.

About the same time the

chartered transport Borneo sailed from Zamboanga for Digos via

Margosatubig, with the cargadores and to pick up

Lieutenant Henry Rodgers with his detachment of Philippine

scouts, the entire party there to concentrate and move out

against the Moro outlaw.

On the 19th of the month the

department commander ordered two companies of the 19th infantry

from Malabang and one company from Parang to

Cabacsalan Island, Captain John Howard commanding the troops of

the 19th Infantry.

The expedition landed at Digos, on Davao Bay, on the afternoon of October 16 and disembarked from the Sabah and Borneo.

While there, they secured the

services of Lieutenant E. C. Bolton, 17th Infantry, governor of

Davao, and Mr. Skinner, an American planter, to accompany them.

The fact of Lieutenant Bolton and the American planter

accompanying the expedition, allayed the fear of the hill tribes

and kept them from deserting their villages

and spreading the news of the expedition.

When the expedition reached the

divide between Davao Bay and the Rio Grande Basin it was decided

that only the ablest men were to proceed on further.

So Lieutenant Rodgers with the scouts, all the cargdaores and

supplies, and all men who had sore feet, who were played out,

etc., were left behind

to follow at their leisure, while the seventy-seven healthy

remaining members of the provisional company were to make a dash

for Datu Ali's rancheria,

stripped of all impedimentia, excepting one day's cooked rations,

and last, but far from least, reserve ammunition.

For the next two days this

little band steadily marched through an extremely hostile

country, over mountains and swamps, crossing swollen streams and

crawling through jungles, by night as well as by day, living on

what snatches of food, such as hardtack and canned salmon, they

had time to bite, and just at

daybreak on the morning of October 22 they approached Datto Ali's

rancheria on the Malala river, after a forced and rapid march of

over 50 miles

over an almost impassable country.

Lieutenant Philip Remington, 22d

infantry, was placed in charge of the advance guard; Captain

McCoy commanded the main body, while Lieutenants

West and Johnson each commanded a detachment that was advancing

on Ali's rancheria from both right and left, so that there was

practically no escape for him.

When within about three hundred

yards of Ali's house, a party of eight Moros armed with spears

and krises was surprised and captured by Captain McCoy,

just as Lieutenant Remington with the advance guard had reached

the clearing around Datu Ali's house.

Seeing Datu Ali and some twelve

armed men sitting on the porch of the house, Lieutenant Remington

with two squads gave the command "Charge!"

and all dashed forward hoping to capture the un-armed party, but

quick as Lieutenant Remington was, wily old Ali was still

quicker,

for in a second's time they all jumped back into the house and

Datu Ali remaining alone on the porch raised his rifle and fired

pointblank,

killing Private Llewellyn W. Bobb, company G, 22d Infantry.

Almost at the same instant Lieutenant Remington raised his revolver and fired, shooting Datu Ali through the body and bringing him to his knees.

Under the cover of a galling fire from his followers he struggled to his feet and endeavored to escape, but was riddled by the remainder of the advance guard.

Datu Ali's followers enraged at

the death of their chief kept up a stirring fire from the

interior of the house, wounding two more of the advance guard.

In the meantime, Lieutenants West and Johnson had cut their way

through the heavy foliage and underbrush on right and left and

advanced on the

double quick, firing rapidly and cutting off all escape.

Captain McCoy then united with Lieutenant Remington and the advance guard.

When Datto Enok excitedly yelled

the all important news, "Datu Ala Muerte," all firing

ceased and recall was immediately sounded. The wounded Moros

were turned over to the tender mercies of Datto Enok, and all the

surrounding houses searched for arms, ammunition and other

munitions of war.

Word was then sent by messengers to all the surrounding rancherias that they had no more to fear.

Datu Ali, the terror of the

valley, was dead, and hostile operations in the Rio Grande valley

were all over. Private Martin L. Bales company K, 22d Infantry,

who was wounded, died within an hour afterward, while Private

John J. Rorke, company G, 22d Infantry, while wounded through the

lungs seemed to do well

and took part in the remainder of the engagement. Shortly

afterward the camp was removed to the Alip river, where

Lieutenant Rodgers with his scouts,

train, supplies, exhausted men, etc., rejoined and the entire

command proceeded on the following day to Buluan, to await the

arrival of vintas and rations

by way of Lake Liguasan.

On the 26th Instant, Captain

Howard, with the 19th infantry, arrived with vintas and rations

when the expedition proceeded to Cabacsalan Island,

where it reported to the commanding general of the department, on

the evening of the 28th and there was disbanded.

Captain McCoy, in speaking of

the conduct of the officers and men on this expedition, says that

it was of the highest order, and recommends for

certificates of merit, 1st Class Sergeant James C. Gunn, hospital

corps (twice wounded in the attack on Peruka Utig's Cotta in May,

1904,)

for particularly meritorious and excellent services throughout

the expedition in caring for the wounded while under a heavy fire

in the attack on Datu Ali.

He also recommends Corporal Barry Smith, company G, 22d Infantry,

the non-commlssloned officer in charge of the advance guard, for

special bravery

in action; Private William R. Hutchinson, company K, 22d

infantry, member of the advance guard, for bravery in action and

fine marksmanship;

Sergeant Lewis A. Carr, company K, 22d infantry, for arduous work

and rare judgment as quartermaster sergeant, in charge of all

supplies and cargadores.

Sergeant Carr often worked day and night and the peculiar

conditions attending the expedition made the care and

distribution of the six days' rations,

which had to last for ten days, a matter of rare importance.

In his report of the expedition,

the department commander takes advantage of his opportunity to

thank Major John J. Crittenden, commanding the 22d infantry,

for the admirable manner in which he carried out his orders and

instructions. He also speaks of the fact that Datto Ali had

terrorized the Cottabato Valley

for months, killing Moros friendly to Americans and threatening

the lives of others. Complaints were made by the hill tribes

living around Simpetan

and the Gulf of Davao that he had looted their villages and

carried off their woman.

The department commander has

called the attention of the division commander to the great

hardships experienced by Captain McCoy

and his command in their march through a country specially

adopted for four-footed animals or winged travellers.

Attention is finally invited to the superb discipline of the

officers and enlisted men of the 22d infantry.

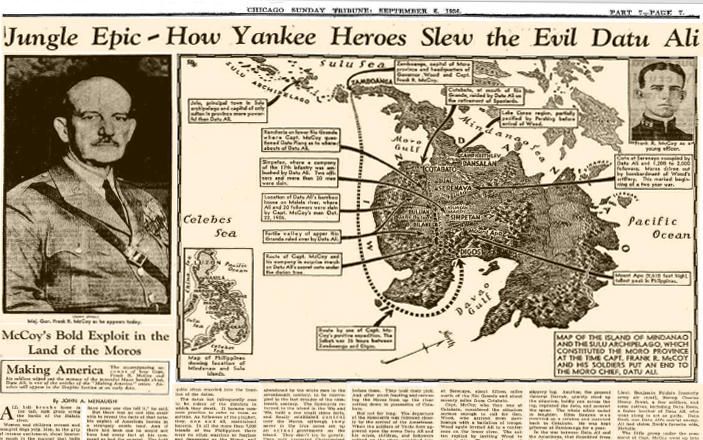

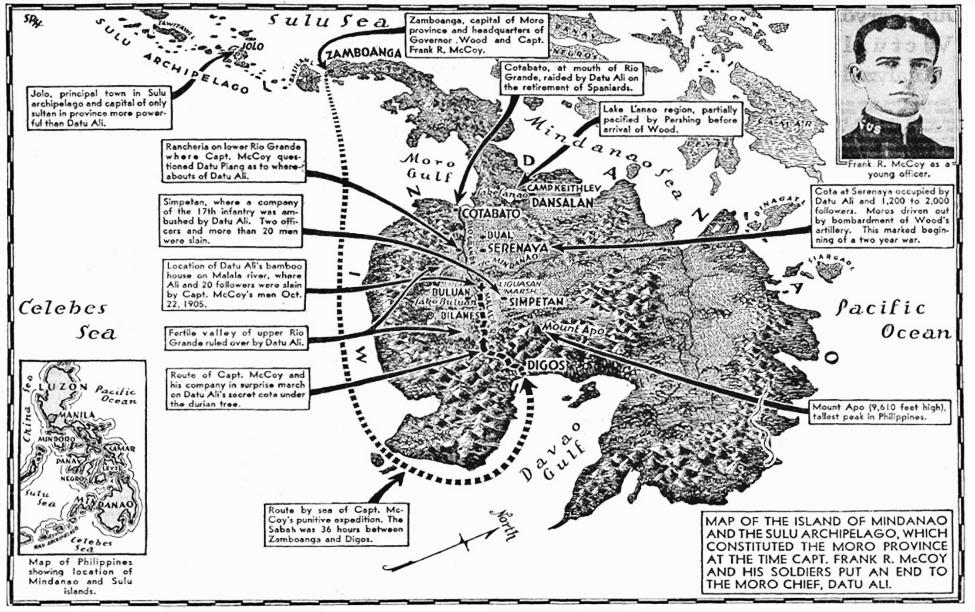

In 1936 the Chicago Tribune

newspaper printed a two page article commemorating the Datu Ali

expedition

as part of the paper's "Making America" series. The

article featured a stylized but detailed map

and also included photos of Frank R. McCoy as a Major General in

1936 and as a young Lieutenant

in the 10th cavalry:

Above: The top section of the first page of the article in the Chicago Tribune Sunday September 6, 1936

From the Chicago Tribune website

Above: The map from the 1936 Chicago Tribune article

From the Chicago Tribune website

Below is the text of the article

from the Chicago Tribune of September 6, 1936. As in the above

articles about the

Datu Ali expedition, this article gives additional details and

information:

Jungle Epic - How Yankee Heroes

Slew the Evil Datu Ali

McCoy's Bold Exploit in the Land of the

Moros

Making America

The accompanying account of how Capt. Frank R. McCoy and his

soldiers wiped out the menace of the powerful Moro bandit chief,

Datu Ali,

is one of the articles of the " Making America "

series. Another will appear in the Graphic Section at an early

date.

By JOHN A. MENAUGH

ALL hell breaks loose in the tall, lush grass along the banks of

the Malala river.

Women and children scream and mongrel dogs yelp. Men, in the grip

of intense excitement, shout hoarsely much in the manner that

bulls bellow. Rifles roar

on every hand, and the din is punctuated by the deep coughs of

heavy revolvers. The air is laden with the penetrating fumes of

smokeless powder.

Death holds carnival on the Malala.

From a barricaded bamboo house under a solitary durian tree come

flashes of fire as weapons of various sorts are exploded toward

the thin ring of khaki-clad soldiers

circling the habitat. The flashes of flame are answered by others

from the circle. The soldiers swiftly close in.

A gigantic man, his gleaming body bare except for a scanty

breechclout, emerges from the low door of the house. In his hands

is a Mauser rifle,

the bolt of which he works furiously as he delivers a stream of

metal jacketed bullets toward the line of soldiers before the

door of the house.

A revolver and twelve rifles--- these are Springfields---speak

simultaneously. The huge man with the Mauser sinks to the ground.

His figure is motionless.

Datu Ali, raider, robber, and woman stealer, is dead.

How Capt. Frank R. McCoy, a young American cavalry officer, more

than thirty years ago put a fatal finish to the depredations of

the powerfully dangerous

Moro chieftain, Datu All, and brought peace to the valley of the

Rio Grande de Mindanao in the Philippine Islands, is a story that

involves:

A company of fearless, fighting Americanos, struggling and

sweating through the Filipino jungles as only heroes can.

Assorted Moros, some hostile, some friendly.

A lonely durian tree, which turned out to be the key to the

success of an avenging expedition.

And a lot of background and foreword that are essential to the

proper unfolding of the story.

McCoy, who since 1929 has been a major general, who saw active

service in France in the World war, and who has been almost

everywhere on strange,

surprising, and highly important missions, would tell you that

the destruction of Datu All was wholly, or almost wholly, due to

luck. He is prone to minimize

his part in the affair. Yet, Without the initiative of young

Capt. McCoy it is doubtful that Datu All, Public Enemy No. 1 of

the Island of Mindanao,

could have been trailed to his doom on the banks of the Malala,

Oct. 22,1905.

"When you write this," said Gen. McCoy not long ago,

" do not make it appear that I am telling the story. First

person pronouns seem a bit too much like boasting.

Just let me tell it all to you as I remember it, and then you

retell it in your own words."

It is true indeed that the general was reluctant to provide the

account of the fateful expedition against Datu All. " Much

better to have some one else tell it," he said.

But there was no one else available to reveal the facts of that

notable exploit of American heroes in a strangely exotic land.

And if there had been one

he would not have had every fact at his command as had the

general. The bold action that brought lasting peace to the valley

of the Rio Grande

was history of the brand that helped make America.

Fire kindled in McCoy's kindly eyes as he relived again the

stirring days spent in the quest of the jungle scourge, Datu Ali.

The story begins properly 415 years ago, when Spaniards first set

foot on the southern islands of what now are known as the

Philippines.

Those first daring explorers found on the islands a native

people, bronze hued and rather small of stature, but quick and

cunning and far more

intelligent than ordinary savage islanders. Because these people

were Mohammedans and of dark complexion, the Spaniards called

them Moros,

the identical Spanish word for another people, the Moors, dusky

Mohammedans with whom the Spaniards had been battling for

centuries

back on the other side of the world.

Ancestors of these Moros had come into the Philippines from

Malaysia in the dim and distant past. They had brought the faith

of Islam with them,

had interbred with other peoples already on the islands, and had

produced a race of upstanding, fearless men and women who asked

no privileges,

who took what they wanted and what they needed. They had their

own nobility, their noblemen generally possessing in their veins

true Arabic blood.

Each nobleman, or datu, had as headman in his household a tall

dignified Arab. These Arabs quite often married into the families

of the datus.

The datus not infrequently rose to be rulers of the districts in

which they dwelt. It became common practice to refer to them as

sultans.

As followers of the prophet, they, one and all, maintained

harems. In all the more than 7,000 islands of the Philippines

there were no other warriors

so fearless and dangerous as the Moros, and no Moros so difficult

to combat as their noblemen, the datus.

Favorite arm of the Moros was the kris, or creese, a wicked,

swordlike cutting weapon. Some of these were straight bladed,

others had wavy edges.

Each tribe was partial to its own particular kind of kris. Datu

Ali, villain of the chapter of history that has to do with

Mindanao in the early 1900s,

was equally proficient with straight bladed and wavy edged kris.

The barong and the campilan were variants of the kris. Moros also

used spears

in warfare and in hunting, but apparently never mastered the bow

and arrow. They took to firearms after the arrival of Europeans,

learned to make

crude muskets and cannon, solved the mystery of the manufacture

of gunpowder, and grew skilful at stealing rifles from the white

men.

The Spaniards who established settlements in the Philippines were

able to Christianize many of the tribes, especially those of the

northerly islands,

but they never made much headway in missionary work among the

Moros. The last named remained throughout the Spanish occupation

more fiercely Mohammedan than Arab or Turk. Though now pacified,

they still adhere to the faith of their ancestors.

Spain made little pretense at attempting to civilize the natives

of Mindanao, the area of which is slightly greater than that of

the state of Indiana.

A few feeble efforts met with failure in the early days, and the

Island was virtually abandoned by the white men in the

seventeenth century,

to be reoccupied in the last decades of the nineteenth century.

The Spaniards returned to the island in the '80s and '90s, built

a few small stone forts,

and finally established control over the Moros, although they

never in the true sense set up an actual government on the

island. They didn't try to govern.

They only protected Christianized Filipinos, Chinese, and others.

It was Gen. Valeriano Weyler y Nicolau, marques of Tenerife,

better known as

"The Butcher" of the Cuban war, who temporarily

pacified the Moros, who whipped their chieftain, an uncle of Datu

Ali, and made the territory in the

neighborhood of Spanish forts relatively safe for Spaniards.

Then came the Spanish-American war in 1898. The defeated

Spaniards moved out of Mindanao in 1901.

After the evacuation of the Spanish garrisons and before the

arrival of American troops in the remote island there flashed

into the picture the then

little known sultan of the upper valley of the Rio Grande de

Mindanao, a great sprawling fertile lowland, crossed by streams,

dotted here and there with rice fields,

and hemmed in on all sides by mountains, at the bases of which

were thick, tropical jungles. This sultan's name was Datu Ali. He

was a strapping fellow

well over 6 feet in height. He and his brother, Djim Bangan, also

a giant of a man, although lacking some of the fiercely warlike

qualities of Ali, moved down

the Rio Grande with their followers and raided the town of

Cotabato [cota means fort; bato means stone; cotabato means

stonefort], which had been

left to their mercy by the Spaniards. Native homes were looted.

The blade of the kris flashed in the sunlight. The earth grew

damp with a deep red stain.

It was much like the sacking of an ancient town by buccaneers,

and almost as bloody. Datu Ali and Djim Bangan ordered all the

women, of the village

paraded before them. They took their pick. And after much

feasting and carousing the Moros from up the river settled down

in possession of Cotabato.

But not for long. The departure of the Spaniards was followed

closely by the arrival of the Americans. When the soldiers of

Uncle Sam appeared upon the scene

Datu Ali and his wives, children, and followers retired up the

river---vanished into the wilds of the upper valley.

The first American commander in that region was Col. Lea Febiger.

As Capt. John Pershing [the general of World war fame] was

pacifying to a degree

the Moros of the Lake L'anao district. to the north of Cotabato,

Col. Febiger was winning the friendship of Datu Ali, sultan of

the upper valley

of the Rio Grande. The Louisiana Purchase exposition was

scheduled to be held in St. Louis in 1903 [it was delayed a

year], and Febiger suggested

that Ali and his wives be included in the group of Filipinos who

were to be taken to the fair. All arrangements had been made to

transport the sultan

and his harem to the United States when some enterprising

American discovered that the Moros were slaveowners and that some

of the native individuals

slated for a trip to St. Louis actually were slaves. Washington

called off Ali's excursion at the last moment.

That was an affront that Datu Alt could not ignore. Moro chiefs

refuse to be treated shabbily, even by governments. And Ali was

more sensitive than

most noble Moros. He had lost face among his people. He broke off

friendly relations with Americans. He was through.

In 1903 Leonard Wood, just promoted to major general, was ordered

to the Philippines, his assignment being to organize a government

in the Moro province

to supplant the mere army post control then in existence. The

province took in all of the Island of Mindanao, except certain

Christian districts, and the

Sulu archipelago, the last named territory ruled over by the only

sultan in the Philippines more powerful than Datu Ali. The

capital of the Moro province was Zamboanga.

Accompanying Gen. Wood to the new American possessions, over

which years later he was to become governor general, was Capt.

McCoy. The young officer

was the general's aid. He was appointed to the council of five

which constituted the executive body handling the affairs of the

new government. This council

ordered roads built, established district governors, and in

general created order out of chaos. There were two army officers

on the council of five,

and three civilians. These men and their subordinates worked

directly through native chiefs.

Gen. Wood realized that if he could bring Datu Ali, most powerful

sultan in Mindanao, to terms he would be going a great way toward

establishing permanent peace.

The general sent word to Ali, inviting the sultan to become

headman of the upper valley as the representative of the American

government. Ali replied that he

would not act under American orders. Hostilities began when Ali

retired to a cota at Serenaya, about fifteen miles north of the

Rio Grande

and about seventy miles from Cotabato.

Capt. McCoy, who then was at Cotabato, considered the situation

serious enough to call for Gen. Wood, who arrived from Zamboanga

with a battalion of troops.

Wood again invited Ali to a conference on the lower river. The

sultan replied by inviting Wood to come to him. The general set

out with his troops for Serenaya.

On the way the Americans were ambushed. A few were wounded. Ali

fell back to the fort at Serenaya, which consisted of a series of

earthworks with bastions,

the whole revetted with bamboo. When Capt. McCoy inspected it

after its capture he found it to be the strongest native fort he

had ever seen.

Wood sent back to Cotabato for artillery. The guns were dragged

through rice fields and jungles to the vicinity of the cota at

Serenaya, where All,

with 1,200 to 2,000 followers, was taking refuge behind the

protection of some sixty native bronze cannon and twenty old

Spanish pieces,

some of large caliber. Gen. Wood turned his gunners loose on the

Moro fort. Shells ripped through jungle foliage. Splinters and

flying earth filled the air.

Surviving Moros stole out of the fort and vanished, leaving

several hundred dead and wounded behind. It was the start of a

two year war.

After the bombardment at Serenaya Ali fled to Bual, pursued by

the American troops. Capt. McCoy went along with the soldiers as

an interpreter,

and it was on this expedition that Djim Banyan, Ali's brother,

was captured under highly amusing circumstances. The big Moro

fled across a wet log

spanning a stream, and stood at bay with an uplifted spear. One

of the American officers fell into the stream in trying to

negotiate the slippery log.

Another, the present General Darrah, quickly sized up the

situation, boldly ran across the log, captured the datu, and

secured the spear.

The whole affair ended in laughter. Djim Banyan was mounted on a

carabao and marched back to Cotabato. He was kept prisoner at

Zamboanga for a year.

In the war between Datu Ali and the Americans that flourished

from the time of the bombardment at Serenaya to the death of the

Moro sultan,

Ali had all the best of it. His espionage was better than that of

the Americans. Peaceful natives were afraid to betray him, for

his vengeance was

far-reaching. He raided up and down and across and back the wide

valley of the Rio Grande. He even went beyond the limits of his

own territory.

He looted villages, put to death those who opposed him, and stole

all the pretty girls upon whom his eyes fell. His warriors

ambushed American

detachments in the jungles, fired their stolen rifles at the

white men who saw nothing to shoot at in the black shadows of the

trees, and laughed as they fled

before the wrath that was next to helpless in a disadvantage such

as that.

In one of these ambushes planted by Datu Ali two officers and

more than twenty men were slain. It was a company of the 17th

infantry, under two young lieutenants,

Woodruff and Hall, that marched into the death trap at a place

called Simpetan, on the edge of the Liguasan marsh, far up in the

valley of the Rio Grande.

Only twelve of the company survived. The Moros captured between

thirty and forty Springfield rifles.

Troops were dispatched up the river to the scene of the ambush.

There was nothing that could be done, however. On the return from

Simpetan Capt. McCoy

was left at Buluan with orders to go up into the hills and warn

peaceful natives against Datu Ali. With McCoy were Lieut.

Benjamin Foulois [recently army air chief],

Bishop Charles Henry Brent, a few soldiers, and some natives,

including Datu Enok, a foster brother of Datu Ali, who went along

to act as guide. Datu Enok

was Datu Ali's mortal enemy. Ali had stolen Enok's favorite wife,

Makalie.

The little group under the command of Capt. McCoy went up into

the jungle country south of Mount Apo, the highest peak in the

Philippines.

McCoy and Foulois were the first American officers ever to

penetrate this isolated region. They came out at a place called

Digos, on Davao gulf.

On the evening after separating from the main force at Buluan the

little party camped on the Malala river. While the natives were

making camp

for the soldiers, Datu Enok and Capt. McCoy stood together gazing

at the colorful panorama before them. The guide pointed out the

peak of

Mount Apo, then called attention to a great pyramidal tree to the

northeast that reared itself above the surrounding landscape.

Between the two men

and the tree was only flat territory, covered with tall grass.

"That's a durian tree," said Datu Enok. " It is

the only one within a hundred miles. Natives come here from over

the whole valley to eat of its fruit."

The tree of this species bears a spherical fruit six to eight

inches in diameter. The inside of the fruit when ripe has the

consistency of custard and,

although it smells to the heavens, the natives like it.

The lone durian tree on the banks of the Malala turned out to be

more than just an attraction to hungry Moros. How it proved the

key

to the collapse of Moro resistance in Mindanao will be revealed

as the story unfolds.

Datu Ali's defiance of American authority dragged on through the

months. Gen. Wood was making ready to return to the United States

on leave,

but before he departed he made another effort to arrange a truce

with the wily Moro sultan. He sent the other of his two aids,

Capt. Ralstead Dorey

and a Syrian doctor, Najab Saleeby, who spoke Arabic, up the Rio

Grande to the rancheria of one Datu Piang, a cunning old

chieftain,

part Moro and part Chinese. Capt. Dorey there conferred with Datu

Ali, who finally agreed to come to terms and yield to the

Americans.

A proposed surrender of arms on the part of the Moro sultan

proved a stumbling block to the proceedings. After three or four

days of parley

Ali vanished in the night. He had been fooling all the while.

And when he disappeared he took with him Datu Piang's favorite

daughter, Minka.

Gen. Wood went away, leaving Capt. McCoy as acting governor. It

was decided to do nothing about Datu Ali until Wood's return,

the plan being to keep negotiations with the elusive Moro alive

until the general could be present to direct them.

The program was changed, however, just before the expected return

of Wood. Brig. Gen. James A. Buchanan had been sent in to assume

command

of the troops in Mindanao, although not to supplant Wood as

governor. McCoy had been relieved of the duties of acting

governor, but still

was a member of the legislative council. The new plan was to make

one more try for Datu Ali.

Capt. McCoy went up the river to Datu Piang's place to see if he

could learn from the old man, whom he knew as " a clever old

coon," the whereabouts

of the slippery Datu Ali. Datu Piang was friendly to the

Americans. But he also was friendly to, or fearful of, Datu All.

For several days McCoy remained

at Piang's rancheria, making no headway at worming the secret of

Ali's whereabouts out of his host. Finally, realizing that he was

getting nowhere

and time was flying, McCoy put the case squarely up to Piang in

words like these:

"Now, Piang, I'm going back, and you haven't told me

anything. I don't want to have to tell Gen. Wood that you have

told me nothing.

I know you know where Ali is."

Piang did not relish the role of enemy to Gen. Wood. He slowly

revealed to Capt. McCoy that he knew where Ali was hiding out.

Six weeks before,

according to Piang, Ali had sent for Minka's mother to nurse

Minka through a spell of sickness. The old woman had been taken

up the river,

through the marsh, or everglades, to the Malala river. She had

returned to Piang's place the day before the arrival of McCoy.

Piang felt that he could tell Capt. McCoy where Ali was

hiding---that is, in a rather indefinite way. He knew that the

soldiers could not go up the Rio Grande

without Ali being informed of their approach. And he also knew

that in telling McCoy that Ali was camped on the Malala he was

not revealing the location

with any great degree of accuracy. There were thousands of places

to hide along the stretches of the winding river.

The old native told the captain that Ali was staying in a house

on high ground somewhere [he wasn't certain just where] on the

banks of the Malala.

Without giving the matter a thought, Piang said that the house

stood under a durian tree.

That was enough for Capt. McCoy.

Back to Zamboanga went McCoy immediately. Gen. . Buchanan was for

dispatching an expedition at once, to capture or kill Datu Ali.

McCoy suggested

a secret expedition, by way of Davao gulf and an overland march

to the Malala river from the east. From Digos, where the

expedition finally landed,

to within fifteen miles of the house in which Datu Ali was found,

was the rankest kind of jungle. The route was over a divide, and

along the bases

of the mountains. McCoy knew that any expedition approaching the

Malala river from Cotabato could have no secrecy---that Datu Ali

would know about it

days in advance of its arrival. The captain also knew that by

going in the back door, so to speak, he would have a chance to

trap the foxy chief.

Gen. Buchanan insisted that McCoy lead the troops against the

Moro sultan.

The, captain therefore chose a company of the 22d infantry, which

was stationed at Camp Keithley on Lake L'anao. He wanted soldiers

from the camp

most remote from the valley of the Rio Grande. He didn't want his

plans to leak out. The soldiers were taken to Zamboanga , with it

understood

that they were going on an expedition to the Sulu Islands.

There were a hundred soldiers and a company of native scouts

under Capt. Henry Rodgers in the little force selected to go

after Datu All. Capt. McCoy

took Lieut. Gordon Johnston [the Col. Johnston killed in a polo

accident in Texas in 1934] as his right hand man. Also on the

expedition were

Lieut. Philip Remington, Lieut. Solomon B. West, Lieut. B. M.

McCroskey, Dr. W. T. Davis, 150 native bearers, Datu Enok, the

sworn enemy of Datu Ali,

and Tomas Torres, a Filipino veteran of Moro wars, whose wife

also had been stolen by Ali. Torres knew Ali by sight.

The expedition sailed from Zamboanga in the little steamer Sabah.

A landing was made at Digos in Davao gulf. McCoy's plan was to

push forward as rapidly

as possible in order to reach the house under the durian tree

before Datu Ali could learn of his advance. The soldiers and

native scouts and bearers

plunged into the jungle, working their way up to the divide near

Mount Apo. The whole advance toward the goal on the Malala river

took six days,

the soldiers, however, marching in the main by night. When the

divide was reached it was found that twenty-three of the soldiers

were played out.

Others of the expedition pushed on toward Ali's hiding place.

Capt. McCoy had in his mind as a possible danger point the

village of Bilanes on the route to Ali's house. He expected to

make a forced march

from the divide by day, then halt for a while, and work around

the village at night. Instead, he miscalculated and blundered

into the village.

It was dark when this happened, and rain was falling. McCoy's

soldiers rushed through the village to the barking of dogs and

the beating of gongs,

and soon were between it and Ali. In the meantime five more men

had been overcome by fatigue. They were left behind, somewhere

near the village of Bilanes.

After stumbling into the little native settlement the troops

rested from 7 o'clock until midnight. McCoy and Johnson made a

reconnaissance as the soldiers slept.

At daylight the advancing column came to the banks of the Malala

river. Two Moros were on the other side, one astride a pony, the

other afoot. Lieut. Johnston

was about to fire his revolver at them when he was restrained by

Capt. McCoy. The captain did not want to give the alarm, and he

was not certain that

the two Moros were messengers sent from the village of the

Bilanes to warn Ali of the approach of the Americans. As it

transpired, however, that is exactly

the mission that the two were on. They rushed to Ali and told him

the soldiers were near, but All refused to believe them until it

was too late. The villagers

had not seen the soldiers as they ran through in the dark. They

had only surmised that the party rushing through was made up of

Americans.

That was why Ali was skeptical.

The Americans and the few scouts accompanying them advanced

rapidly in the early gray of the morning, crossing and recrossing

the river several times

until they came to the ford nearest the house under the durian

tree. A guard of seven men who had been watching this crossing

had departed

for breakfast shortly before the weary American soldiers arrived

at 6 o clock. That was one of the circumstances that McCoy

considered sheer luck.

Lieut. Remington was ordered to go forward as speedily as

possible with seventeen picked men---his job to capture or kill

Datu Ali before the Moros

could organize resistance. Remington and his men advanced at a

dog trot through the tall grass. Lieut. Johnston with a platoon

moved to the left

to cover the river. Lieut. West and others of the soldiers

proceeded to the right to keep any of the enemy from fleeing on

that side by the way of the river.

Above the waving grass Capt. McCoy saw the spears of the seven

Moro guards returning to the ford after having had their coffee.

These guards

had missed Remington and his soldiers. McCoy indicated to the men

with him that he to lake the seven without sounding an alarm, and

just as his soldiers

pounced upon the natives there came from the vicinity of the

bamboo hideout of Datu Ali the sound of gunfire.

When the shooting began at the house McCoy ran ahead to join

Remington. As he broke out of the taIl grass about a hundred

yards from the house

he saw a line of his soldiers firing into the bamboo structure.

He saw both Datu Enolk and Tomas Torres firing toward the house.

He saw Remington

firing with a .45 caliber revolver. The expedition had armed

itself at Zamboanga with pistols heavier than the then regulation

.32 caliber service weapons,

in the knowledge that Moros required a weight of lead to stop

them.

McCoy saw a gigantic Moro emerge from the door of the house. The

man was without sarong or turban---nude except for a small

breechclout.

In his hands he held a rifle---a Mauser, a weapon of a make

popularized among the Moros by the Spaniards. The big Moro was

shooting fast.

One of his bullets killed a man standing near Remington.

Remington fired his revolver at the man with the Mauser. At the

same time a dozen other American soldiers let loose their

Springfields at the man.

Every bullet hit him. He fell.

"That was Ali," shouted Tomas Torres.

McCoy called to Remington to cease firing. Johnston, on the bank

of the river, had heard the name of Ali shouted above the din of

battle.

He saw a Moro make for the river and thought it was Datu Ali

escaping. The lieutenant jumped into the river himself, and

almost drowned,

but the fleeing Moro got away, the only one to escape from the

great bamboo house that stood only sixty feet from the bank of

the Malala under the durian tree.

As Remington emerged from the cover of the tall grass he bad seen

a group of Moros taking coffee on a platform in front of the

house. He rushed at them,

firing as he ran. The Moros retreated into the house, lay down on

the floor, and fired through loopholes with Springfields and

Mausers at the soldiers on the outside.

There were twenty-one Moro men in all in the house, and in

addition were the wives and some of the children of Datu Ali.

Only Ali of all the Moros stood up

to fight it out with his enemies.

Datu Enok called to those in the house to surrender. A woman's

voice answered that all of the men had been killed. In the place

were twenty women

and children, nearly all of whom had been wounded. But no woman

or child was slain.

Dr. Davis attended to the wounds of the women and children, as

well as those of the Americans who had received bullets in the

fight. Two Americans

were killed, and three wounded. Minka, the daughter of Datu

Piang, at first would not allow the doctor to dress her wounds.

As Capt. McCoy talked to her,

urging her to accept the physician's care, he turned toward the

house and beheld an amazing sight.

A woman, stark naked, was coming out of the house. In her arms

she held a baby. The woman was badly wounded. She was Datu Enok's

stolen wife, Makalie.

Finally all the wounds were dressed, including those of Minka.

The dead were buried, and the women and children collected

together and sent down the river.

The soldiers recovered the rifles taken in the ambush at

Simpetan. Datu Enok, at his own request, got back his wife. The

troops moved to Buluan on Lake Buluan,

where they took up a defensive position and waited for other

troops sent in from Cotabato by Gen. Buchanan.

Then Capt. McCoy and his soldiers went down the river, through

the sunbathed valley of the Rio Grande, in which no hostile shot

has been fired

since that eventful day of Oct. 22, 1905.

"What was Datu Ali wearing when he was killed?" Datu

Piang asked Capt. McCoy weeks later.

"Only a breechclout," rejoined the captain.

"Didn't he have on a shirt? " queried the old man.

"No," said McCoy.

"That's why he was killed. He wasn't Wearing his magic

shirt," confided Piang.

It seems that All, as an alleged descendant of Mohammed.

possessed a bulletproof shirt of silk, and a pot of sacred oil

that was guaranteed to keep him safe from harm.

But no charms were working at that fateful hour when he stopped

more than a dozen bullets on the banks of the Malala.

Article from the Chicago Tribune Sunday September 6, 1936

From the Chicago Tribune website

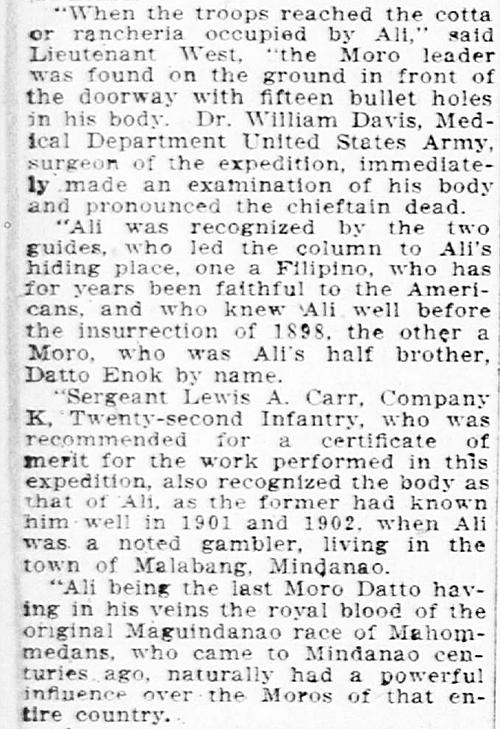

Incredibly, within a few months,

a report originating in Manila, that Ali was not killed,

but was still alive on Mindanao, appeared in US newspapers:

From the San Francisco Call, Saturday, May 26, 1906

CDNC California Digital Newspaper Collection

Within two days articles were

published

to contradict the report that Ali was still alive:

Article from the Los Angeles Herald, Monday, May 28, 1906

CDNC California Digital Newspaper Collection

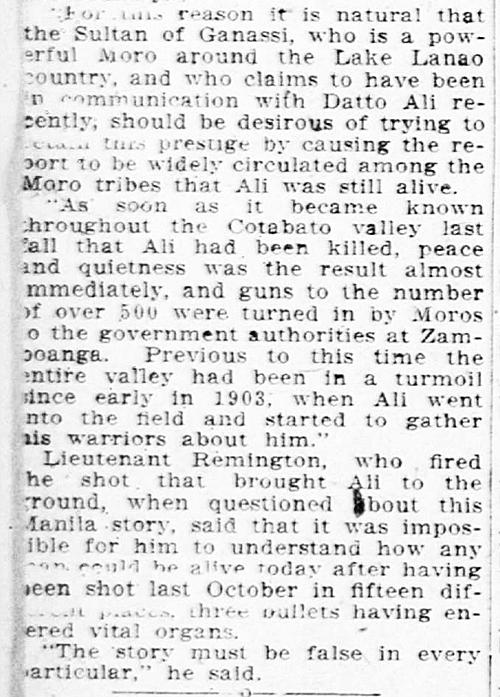

Since the 22nd Infantry was now

stationed in San Francisco, a newspaper in that city was able to

get a more

detailed account from the two officers of the 22nd Infantry who

were part of the mission, and had seen Ali's body.

1st Lieutenant Solomon B. West and 2nd Lieutenant Philip

Remington were interviewed for the following article.

At the end of the article Remington, ..."who fired the shot

that brought Ali to the ground", remarked that Ali

had been shot ..."in fifteen different places, three bullets

having entered vital organs."

Article from the San Francisco Call, Monday, May 28, 1906

CDNC California Digital Newspaper Collection

Annual Reports of the War

Department for the Fiscal Year ended June 30, 1906,

included this description of the Datu Ali episode:

Brigadier General Tasker H. Bliss Commanding Department of Mindinao for the period July 1, 1905 to April 12, 1906

Philip Remington

Undated photo by Amy Griffis from Ancestry.com

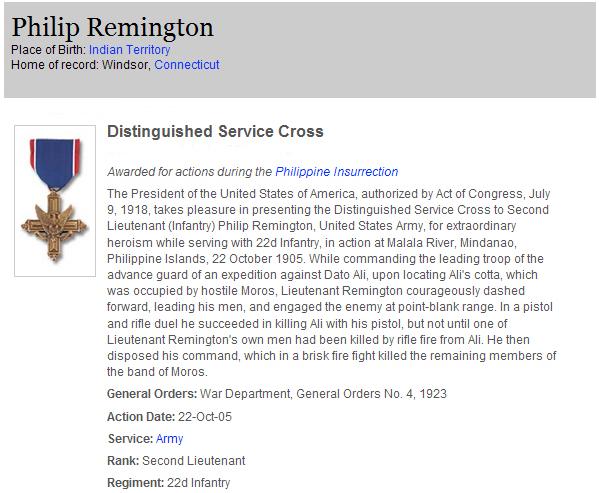

In 1923 the Army awarded the

Distinguished Service Cross to 2nd Lieutenant Philip Remington,

for his actions on October 22, 1905, during the expedition which

finally brought an end to Datu Ali.

The citation for that award is below:

For an account of one of the

22nd Infantry Soldiers who was part of the Provisional Company

which tracked down and killed Datu Ali, go to the following link

on this website:

SGT Grover Hart - Going after the Datu Ali

For an extremely detailed account of the hunt for Datu Ali, see the book:

MOROLAND The History of Uncle Sam

and the Moros 1899-1920

by Robert Fulton

Tumalo Creek Press, Bend, Oregon 2007, 2009

ISBN 978-0-9795173-0-3

Robert Fulton, the author of the

book above, has many photos, maps, and much information

on the pursuit of Datu Ali on his website. Click on the following

link to visit the website:

¹ BULLETS and BOLOS Fifteen Years In The Philippine Islands

by John White

The Century Company, New York & London 1928

Additional sources were:

HISTORY OF THE Twenty-second United States

Infantry 1866-1922

Published by the Regiment 1922

Returns from Regular Army Infantry

Regiments, June 1821–December 1916. NARA microfilm

publication M665

National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

Annual Reports of the War Department for

the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1904 Volume III

Reports of Division and Department Commanders. Washington:

Government Printing Office 1904

Annual Reports of the War Department for

the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1905 Volume III

Reports of Division and Department Commanders. Washington:

Government Printing Office 1905

Register of Enlistments in the U.S. Army, 1798-1914; (National Archives Microfilm Publication M233

Home | Photos | Battles & History | Current |

Rosters & Reports | Medal of Honor | Killed

in Action |

Personnel Locator | Commanders | Station

List | Campaigns |

Honors | Insignia & Memorabilia | 4-42

Artillery | Taps |

What's New | Editorial | Links |