![]() 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry

1st Battalion 22nd Infantry ![]()

The 22nd Infantry At Spring Creek, October 1876

"US Army -- Infantry Attacked By Indians -- 1875"

An illustration from The

US Army and Navy 1776-1899, published in 1899

by the Werner Company of Akron, Ohio

The painting shows

Infantry commanded by a dismounted officer forming skirmish lines

and firing at hostiles

while the wagons they are protecting can be seen in the upper

right.

In the latter part of 1876 the

command of Colonel Nelson Miles, which at the time was a major

element

of the Army's campaign against the Sioux, was ordered by the War

Department to cease operations

and camp for the winter months at the mouth of the Tongue River,

where it meets the Yellowstone River.

This was deep in Montana Territory, in what is now the State of

Montana.

At this time of the year supply

boats could go no further up the Yellowstone River than the mouth

of Glendive Creek. Six companies of the 22nd Infantry were

detailed to meet the boats at Glendive,

and bring the supplies by wagon train to Miles' Tongue River

encampment.

From October 11 through October

16 of 1876 these wagon trains of the 22nd Infantry

were met with attacks by the Sioux, for about half the distance

the trains had to travel. ¹

¹ Webmaster 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry

1st Lieutenant Oskaloosa M. Smith

Smith served with the 22nd Infantry from 1869 to 1890

(Website Ed., On October 26,

1876 Oskaloosa Smith wrote the following account of the wagon

trains

as they moved to resupply the encampment at Tongue River.)

DURING THE LAST CAMPAIGN OF THE

SUMMER, commencing August 8 at the mouth of the Rosebud and

ending at this camp

on the 6th of September, scarcely a wild Indian was seen. The

season of operations was ordered to close on or before October

15th,

and troops were ordered to be cantoned for the winter at the

mouth of Tongue River. The entire 5th Infantry was sent there to

commence building,

so that the troops and stores might be protected from the severe

winter climate, and no time was lost. Six companies of 22nd

Infantry were left at this point

[cantonment at Glendive Creek on the Yellowstone] to receive the

stores from the boats, which could go no further up the river,

and convoy them to Tongue River. Afterward, added to this force

were two companies of 17th Infantry. These were all small

companies,

numbering about 35 men each. They had performed the escort duty,

making nearly three trips each month with a train of 100 wagons,

without molestations by Indians, until the last trip.

On the 10th inst. at noon, the train left here, and that night

camped on Spring Creek, 14 miles out. The next morning they were

surrounded

and attacked by a large number of Indians, and in the skirmish

numbers of mules were wounded, which caused a stampede and some

loss of animals.

The escort was so harassed that they were compelled to either

abandon several wagons and some property, or else to return to

this place;

the latter course they prudently pursued, arriving late on the

evening of the 11th.

The train was refitted and started again on the 14th, the

commanding officer of the station, Lt. Col. [Elwell S.] Otis,

taking command of the escort,

consisting of C and G of the 17th Inf., and G, H, and K of the

22nd Inf., being a force of 11 officers and 185 men. The roster

of officers was as follows:

Lt. Col. Otis, 22nd Inf.,

Commanding

1st Lt. [Oskaloosa M.] Smith, 22nd Inf., Battalion Adjutant

Act. Asst. Surg. [Charles T.] Gibson, Surgeon

Co. C, 17th Inf., Capt. [Malcolm] McArthur, 2nd Lt. [James D.]

Nickerson

Co. G, 17th Inf., Capt. [Louis H.] Sanger

Co. G, 22nd Inf., Capt. [Charles W.] Miner, 1st Lt. [Benjamin C.]

Lockwood

Co. H, 22nd Inf., 1st Lt. [William] Conway, 2nd Lt. Sharpe

Co. K, 22nd Inf., Capt. [Mott] Hooton, 2nd Lt. [William H.] Kell

±

1st Lt. Benjamin C. Lockwood Co. G 22nd Infantry |

1st Lt. William Conway Co. H 22nd Infantry |

Capt. Mott Hooton Co. K 22nd Infantry |

2nd Lt. William H. Kell Co. K 22nd Infantry |

Above: Portraits of 22nd Infantry officers who were present at the Spring Creek encounters.

(Portraits added by the website editor.)

At 10 o'clock A.M. [October 14]

the escort and train moved out gaily. The day was beautiful and

every man was in good spirits,

feeling that they would meet the enemy before returning. That

night camp was made in the beautiful bottom of the Yellowstone,

11 miles away.

Early in the evening a thieving pack of Indians approached the

camp and were fired upon by the sentinels. They beat a hasty

retreat,

leaving a pony with all its trappings and a leg broken. There

were no more alarms that night.

At daybreak the next morning [October 15] the train was on the

move, drawn up in four lines and surrounded by the escort

which was disposed as follows: advance guard, Co. H., 22nd;

advance right and left flankers, Co. C, 17th; right flank rear,

Co. G, 22nd;

left flank rear, Co. G. 17th; rear guard, Co. K, 22nd. It was

Sunday morning and a prettier one never broke forth.

Upon gaining the entrance to Spring Creek three miles from camp,

three men joined the train, who proved to be scouts from

General [Colonel] Miles' command at Tongue River. They were en

route, four in number, from General Miles with dispatches for

Glendive Creek;

on Saturday afternoon [October 14] they were attacked at Spring

Creek by a large number of Indians, one of their number was

killed,

and all their horses were either killed or badly wounded. The

remaining three men were driven into the bushes, were they kept

the Indians at bay

until the darkness of night let them escape and they were thus

enabled to join our troops. The body of the dead scout was found

and buried.

He was not at all mutilated and his gloves were on; evidently the

Indians had not found him, but his gun and ammunition could not

be found.

About this time the Indians made

their appearance on the left side and in front, and opened fire

on Scout [Robert] Jackson and Sergeant [Patrick] Kelly,

Co. F, 22nd Inf., who were mounted and in advance. They had run

into a large party of Indians, and after discharging their rifles

at them,

they fell back, closely followed by about thirty, their clothing

being literally riddled by bullets but their bodies entirely

unharmed.

These two men did a great deal of scouting, coming in close

quarters several times with the Indians, and showed a great deal

of pluck and bravery.

The number of Indians kept increasing; the left flank advanced

and the advanced guard charged them, opening the way for the

train,

which was enabled to ascend to the high table land. Then to our

front signal smokes were raised, which were immediately answered

by some vast ones off toward the Yellowstone, and Indians were

seen coming from all directions, until the train was surrounded

by from 400 to 500.

During this time we had gained the ridge and hills leading down

into Clear Creek and here the enemy had taken position

expecting to prevent our progress, but skirmishers were sent

ahead and the road was cleared, so that we gained the creek

and watered the stock in full view of the foe. But they were not

idle; they collected on the further side and set afire to the

prairie,

expecting to burn us out and to advance under cover of the smoke

and signally defeat us, but our troops gallantly charged them,

answering the Indian yell, and drove them in all directions, so

that the train could move on, though it had to pass rapidly over

the line of burning grass.

As soon as the top land was

reached beyond Clear Creek, the enemy came in strong force

against all parts of the escort.

There were eighty-six wagons to guard, but they were in four

lines and surrounded by our skirmishers. The prairies were

burning,

the smoke was suffocating, and the enemy hurled his whole force

with desperation against the train, bent upon its capture,

so that he would be well provided with food and ammunition, but

they were kept at some distance by the advance upon them of the

skirmishers,

and not a shot damaged the train. The roar of musketry was

terrific. There was no artillery; it was simply an infantry

fight.

They were repeatedly charged in front by C, 17th, and H, 22nd,

and in the rear, which was the most pressed, by G, 17th, and K,

22nd.

Company G, 22nd, during all this time, had a galling flank fire

upon them.

This was kept up under a march of 15 miles until nearly 5

o'clock, P.M., when the train was corraled for the night,

and shots were still exchanged until 7 P.M., when it became too

dark to see. In this struggle a number of Indians were knocked

from their horses;

many of the latter were killed and a number were running around

riderless. These Indians had never before come in close range of

infantry,

or been subjected to such a musketry fire.

It was expected that they would

the next morning be on us again, but we moved quietly from our

camp.

After going a mile or more a shot was occasionally fired. About

this time a note from Sitting Bull, written by a half-breed

Frenchman

[John Bruguier], was found on a stake near the road, demanding

reasons for traveling over the road and scaring the buffaloes,

and ordering the troops back, telling them to leave rations and

powder or he would fight them again, and signed

"your friend, Sitting Bull. Please write soon." No

attention was paid to the letter.

After the troops had passed Bad Route Creek, seven miles from the

night's camp, two men came forward bearing a flag of truce.

They were allowed to enter the lines, and were found to be Indian

scouts from Standing Rock Agency with dispatches

from General [Lieutenant Colonel William P.] Carlin. They had

been ordered to visit hostile camps on business and had just

arrived that morning.

They said that the hostiles had met with considerable losses the

day before and wanted to come in to make peace.

Word was sent to them that a few of their headmen might come in

unarmed. They did so, stating that they were tired of fighting

and wanted to make peace. They wanted ammunition to kill

buffaloes, and food for present use, and they would leave at

once.

They were told that ammunition could not be furnished them, but a

small quantity of rations would be given them,

which was accordingly done and they left us in peace.

During this fight several men were struck with spent bullets, and

only three men were wounded—Sergeant [Robert] Anderson

and Private [John] Donohoe, Co. G, 22nd Inf., and Private

[Francis] Wraggle [Marriaggi],Co. G, 17th Inf.

The Indians were poor marksmen. Our men were under fire for a

long time and it is wonderful that no more men were hurt.

All of our troops showed great fortitude and bravery and many of

the men were recruits. . . . ±

Robert Anderson was born in New York

City, New York in 1848. He enlisted in the Army on June 10, 1872

at Fort Columbus, New York

and was one of 100 recruits assigned to the 22nd Infantry on

September 26, 1872 at Fort Randall, Dakota Territory. At an

unknown date between March 1873 and October 1876 Anderson was

promoted to Sergeant. He was one of two 22nd Infantry soldiers

wounded in the encounter at Spring Creek on October 15, 1876 as

recounted in Smith's letter above. Anderson served two

enlistments

in Company G 22nd Infantry before being discharged at Fort Clark,

Texas on June 10, 1882.

John Donohoe was born in Ireland in

1844. He enlisted in the Army on December 5, 1871 at Fort

Columbus, New York

and was one of 100 recruits assigned to the 22nd Infantry on

September 26, 1872 at Fort Randall, Dakota Territory.

He was one of two 22nd Infantry soldiers wounded in the encounter

at Spring Creek on October 15, 1876

as recounted in Smith's letter above. At the expiration of his

enlistment Donohoe was discharged at Fort Buford,

Dakota Territory on December 5, 1876. ²

² Webmaster 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry

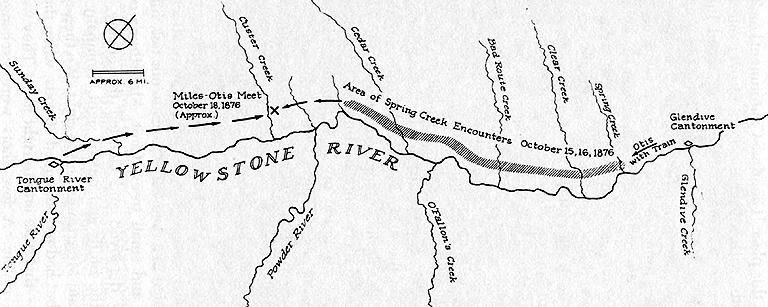

Map of the Yellowstone

River

The shaded portion shows the area of the encounters between

the Sioux and the wagon trains of the 22nd Infantry.

Map from:

Battles and Skirmishes of the Great

Sioux War, 1876-1877 The Military View

Compiled, edited and annotated by Jerome A. Greene

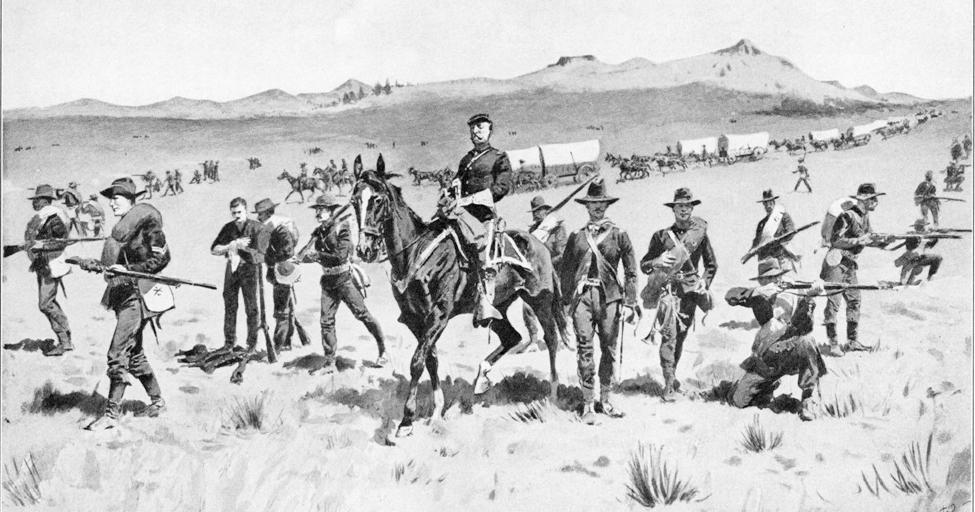

"PROTECTING THE WAGON TRAIN" by Frederic Remington from his book Drawings published in 1897.

In the above illustration Remington

shows U.S. Army Infantry escorting wagons. Mounted on his horse

is a Company Commander.

To the immediate right of him is his subordinate Company officer.

Enlisted men form skirmish lines in front and on either sides of

the wagons.

The 22nd Infantry escorting the wagons from Glendive Creek to

Tongue River would have looked much like the above illustration.

2nd Lieutenant Alfred. C. Sharpe

Sharpe served with the 22nd Infantry from 1876 to 1893

(Website Ed., Lieutenant Sharpe wrote the following account at Glendive Cantonment, October 28, 1876.)

. . . We left this place

[Glendive Cantonment] on Tuesday, October 10th, with a valuable

train of over one hundred wagons.

The escort consisted of Co. K, 22nd Inf., Capt. Hooton and Lt.

Kell; Co. C, 22nd Inf., Lt. Conway and myself.

We encamped the first night on Deadwood Creek, about 14 miles

from this post and about two miles from the Yellowstone.

We had received intelligence, before starting, that 600 lodges of

hostile Sioux had set out for the Yellowstone

and that they probably intended to intercept us. All afternoon we

noticed vast columns of smoke rising in the distant horizon;

they were signal fires heralding our approach. At about 11 P.M.

we heard the report of a musket, and upon inquiry,

we ascertained that one of the pickets saw a man stealthily

approaching our lines, who, upon being challenged, fled.

Quiet was soon restored, and our camp was again wrapped in

profound repose.

At 3:30 A.M. we were aroused by

the sharp reports of a dozen rifles on the surrounding hills.

Hurrying out of my tent,

I saw the flashes of the muskets on the bluffs 500 yards distant.

Bullets came hurtling and whistling by or tearing up the ground

at my feet.

Finally, their fusillade ceased—we did not return a shot. We

busied ourselves getting breakfast and packing our tents and

blankets for the march.

Daylight revealed to us the loss of 57 mules. They had been

stampeded and run off by the Indians.

At sunrise [October 11] we resumed our march. Scarcely had the

rear guard—Capt. McArthur's company—got fairly under

way,

when they were attacked by a party concealed in a ravine 200

yards to our left, filled with underbrush and small trees.

Capt. McArthur's company immediately deployed and charged the

enemy, driving them over the bluffs and out of sight.

Company H supported Captain McArthur's on the right. We then

resumed our march, but had not advanced 80 rods,

when they again opened fire—this time on the right flank.

They were concealed in a ravine. A few shots were exchanged,

but without stopping the march. Looking back, we could see them

literally swarming on our campground.

Their numbers were being rapidly augmented and they became bolder

and more aggressive. All day long they hung on our rear,

occasionally sending a ball whistling through our ranks.

Embarrassed as we were by the loss of so many teams,

the progress of our heavily-laden wagons was very tedious, and as

the hostiles seemed to come swarming from every direction,

now attacking us on the rear, on the flanks, and in front, it was

decided to turn and fight our way through to Glendive.

As we headed for home, the firing gradually ceased, the Indians

seeming nonplused by this move.

We arrived at this post about 9 P.M., Wednesday evening, October

llth.

After two days' rest, Col. Otis

of my regiment took command, and increasing the escort to five

companies by the addition

of Company G, 17th Infantry, Major Sanger, we again set out [on

October 14], determined to go through to Tongue River

if fighting could take us there. We also had three Gatling guns.

The first day we marched ten miles. That night at eight o'clock

we were all "turned out" by a shot on the picket line.

Two cavaliers had approached, and being challenged by the

sentinel,

turned in flight. But his swift bullet overtook them and next

morning we discovered outside the line an Indian pony with a

broken leg;

it had saddle, bridle, blankets, and picket rope, just as they

had been abandoned by the dusky rider the night before.

We resumed the march at about 7 o'clock [October 15]. It was the

"peaceful Sabbath," a lovely day.

My company was the advance guard, and as we strode along on that

bright morning, I was thinking "how pleasant it would be

to be away back in the States today to hear the church bells

ringing and to see the good people coming into church;"

and I almost imagined I could hear the sweet tones of the organ

and the words, "The Lord is in his holy temple;

let all the earth keep silence before him," when suddenly

from the bluffs ahead came the sharp, quick reports of musketry,

and then the air was rent with screams and yells the most

diabolical I ever heard. Two of our scouts had gone ahead

and had discovered a large bank of redskins awaiting our

approach. They sent a shower of bullets after the scouts,

who came flying down the hill like mad men. The Indians were

close upon them and, indeed, it was a chase for life.

One of the scouts lost his hat. An Indian dismounted, picked it

up, and rode off. One of the scouts had the cloth in the shoulder

of his coat

torn open by a bullet. The other had a hole through his moccasin.

My company was immediately deployed "left front into

line" and I was detached with ten men from the right to take

position

on a very high hill on our right, while the main body of the

company under Lt. Conway charged up the acclivity and after a

short struggle,

in which several Indian saddles were emptied, drove the enemy

from the bluffs. The fight had now fairly opened and from that

moment

until the sun sank to rest—twelve long hours— we fought

the fiends. About two o'clock, hot, thirsty, and weary,

we reached Clear Creek—5 or 6 miles perhaps from our camp

and about 16 miles from here. This creek flows through a deep,

rocky ravine, two hundred feet below the level of the plain. The

hostiles had taken a strong position on the opposite side

commanding the valley and all approaches to the stream. But we

must cross it, or consider ourselves defeated.

The Indians were hourly

reinforced until now they numbered upwards of three hundred. We

had but 180 muskets in line.

One of the Gatling guns was placed in position, and under its

cover my Company H, being the advance guard,

made a rush for the valley; as we filed through it along the

stream the Indians devoted their best shots to us.

Sergeant H of my company was marching about two paces from me

when he was struck with a thump in the breast by a spent ball,

which fell, harmless, at his feet. They soon got the range and

bullets came hissing about our heads and tearing up the ground

all around

and about us. Finally, we reached the foot of the opposite side,

and with a cry, we charged up the hill. The Indians then set fire

to the tall grass

which was dry as tinder. The smoke was blinding and the heat

intolerable, but rushing onward and upward, we gained the crest

and again drove the villains before us. Panting and exhausted,

the men sank down, completely overcome. But we had cleared the

way,

and we soon saw the long, white train of wagons climbing the

hill.

The firing now became incessant. They were on all sides of us. We

were completely surrounded.

Down in the valley the reverberations of the musketry was

deafening. As the train slowly climbed the hill and the

rearguard—

Company K, 22nd Infantry, Capt. Hooton and Lt. Kell—

descended into the valley, the Indians closing in on them in

great numbers.

A report came that their ammunition was failing and another

thousand rounds were sent back to them. Major Sanger then turned

back

to the relief of Capt. Hooton, as he was in imminent danger of

being cut off. The enemy, having the vantage ground,

waxed bold and charge after charge was made with varying success.

The prairie was fired all around

us; we met the fires with counter-fires. Time and time again

would they bring us to a dead halt,

and a stubborn fight would ensue for possession of the road.

Finally, the fire on the right flank ceased and they commenced

enfillading our lines

on the left, at the same time holding us at bay at front. Lt.

Conway with ten men from the right of Company H was detached to

go ahead

and clear the way, while I was left with the remainder of the

company on the left. Company G, 22nd Infantry, was advancing to

our support;

when about ten paces from us, I saw a man in its lines drop like

a log; he was shot in the knee. After a half-hour halt, we again

prevailed

and wound onward. The prairie was ablaze all around us, rendering

our passage in the road at certain places quite difficult.

The scene around me reminded me of the rhetorical descriptions we

so often read of Napoleon's smoking wake.

We left a blackened, desolate waste behind us. Perhaps our little

conflict of a single day may not compare with his mighty

struggles,

but it was enough for about 180 men to attend to. Fighting a

civilized enemy is perhaps rough work, but battling with fiends

incarnate,

highway robbers and midnight assassins, "shapes hot from

Tartarus," together with fire, smoke, hunger and thirst,

and the horrible fate of the captive at the stake in prospect is

quite a different mode of warfare.

We were now on the high prairie,

far enough from wood and water. The enemy had possession of the

creek and to approach it was death.

The sun was sinking below the horizon, and it was decided to form

our corral and go into camp—if sleeping a la belle etoile

can be called "camp."

Rifle pits were dug around the entire corral at 500 yards from

it, and you may believe there was little sleep in our camp that

night.

Every available man was on picket. I rolled myself up in a

buffalo robe and with a canteen for a pillow slept with "one

eye open."

The firing had gradually subsided. The last shot was fired about

7 o'clock, and after making many attempts to burn us out by

firing the prairie

on every side, the fiends withdrew until the morrow. Their loss

had been heavy. We saw many ponies running about riderless.

One of our scouts came so close upon the Indians at one time as

to kill one with a revolver. We had set out with 10,000 rounds of

ammunition,

6,000 had already been expended, and here we were miles from the

post and surrounded by the enemy. A gloomy prospect to be sure.

The next morning [October 16]

they again opened on us just after breakfast. The fighting was

not so heavy, but there was not a minute in the day

that we did not have a bullet hissing by. I have always read of

bullets whizzing and hurtling. They could not have come from

Indian muskets.

Their bullets hiss. The firing gradually subsided by 11 A.M., and

the Indians began assembling in a body on an eminence half a mile

ahead of us.

One of their number had a white flag and wore a white jacket. As

we approached he came at a gallop, accompanied by another

with a white handkerchief, or rag, on his head. They presented

Col. Otis a letter from Col. Carlin, commanding at Standing Rock

[Agency, Dakota],

certifying that they were friendly scouts, had just arrived from

Standing Rock, and were en route to hostile camps on official

business.

They also presented the Colonel a letter from Sitting Bull, which

you have doubtless already seen in the official reports.

They said Sitting Bull was encamped nearby and desired to have a

pow-wow.

Half an hour later a glittering cavalcade approached and was

received by the Colonel. Sitting Bull [Sharpe mis-identified this

Indian]

declined to dismount, and had a private secretary whom our

interpreter had to address, and who then communicated with

General Sitting Bull.

After half an hour's talk, in which they were "mad"

because we were running through their country and driving all

their buffalo away,

it was agreed that Uncle Sam should give four boxes of crackers

and three sides of bacon, in consideration of which res

frumentaria

they would no longer molest us. The food was left in the road and

we moved on. As a method of expressing his profound gratitude,

one warrior brought up his gun and sent a bullet hissing over our

heads, just to frighten us perhaps—the cunning creature.

The rest of our march was not at all exciting, except when the

buffalo began to increase in numbers. We saw thousands of them,

also of antelope.

There is abundance of game in this country and the climate is

simply glorious. It is all a delightful experience to me, of

course. . . . ±

In the Regimental history of the 22nd Infantry

it is recorded that LTC Otis commended his command

for their actions in the above encounters. His report stated

" I cannot speak too highly of the conduct of both

officers and men.

The officers obeyed instructions with alacrity and executed their

orders with great efficiency. They fought the enemy twelve hours,

and fired during that time upwards of seven thousand rounds of

ammunition. They defeated a strong enemy,

who had defiantly placed himself across our trail with the

deliberate purpose of capturing the train,

and gave him a lesson he will heed and never forget." ³

³ Webmaster 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry

± Battles and Skirmishes of the Great Sioux War, 1876-1877 The Military View

Compiled, edited and annotated by Jerome A. Greene

Published by the University of Oklahoma Press

The book is available at:

TROOPS GUARDING THE SUPPLY TRAIN by Frederic Remington

A dismounted officer

commands as his men fire at attackers. Their supply train can be

seen

in the upper right. Identifed as Infantry by the soldiers

carrying their canteens, haversacks

and blanket rolls. They are using the long barreled Springfield

rifles while Cavalry would be

using short barreled carbines.

From: INFANTRY Part I:

Regular Army by John K. Mahon and Romana Danysh

Army Lineage Series United States Army Washington, D.C. 1972

**********************

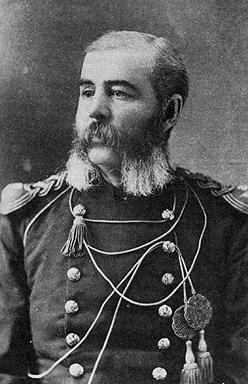

Lieutenant Colonel Elwell S. Otis

In command of the wagon trains which were ordered to resupply the US Army encampment at Tongue River

Otis served with the 22nd Infantry from 1866 to 1880

The following are the official reports of the

above actions, as presented to the Secretary of War by LT COL

Otis and CPT Miner

of the 22nd Infantry. The are taken from the Annual Reports to

the Secretary of War 1877-1878.

HEADQUARTERS BATTALION,

TWENTY-SECOND INFANTRY,

Glendive Creek, Montana, October 13, 1876.

SIR : I have the honor to inform

you that a loaded train started from this station for Tongue

River on the 10th instant, under the command of Capt. C. W.

Miner,

Twenty-second Infantry, and returned the next day, the reasons

for -which are fully set forth in the accompanying report of

Captain Miner.

I have caused the train to be reorganized and will start with it

myself to-morrow morning with companies C and G, Seventeenth

Infantry, and G, H, and K,

Twenty-second Infantry, which force will have one hundred and

eighty rifles; I will also take a section of Gatling guns,

calibre 50. I have so few serviceable horses here

that I cannot have more than three or four mounted men. I am

satisfied from all the information I can gather, that there is a

large force of Indians in the country,

who seem to be bold and defiant; they have been hovering round

this camp on both sides of the river for the past two days; and

no doubt it is their plan to attempt

to break up the communication between this place and Tongue

River; but I think we can pass through the country with the force

I am taking. I leave this camp

under the command of Captain Clarke, Twenty-second Infantry, with

his company (I), and with the men attached he will have eighty

rifles and one Gatling gun, calibre 45.

Very respectfully, your obedient

servant,

E. S. OTIS,

Lieutenant-Colonel Twenty-second Infantry, Commanding.

ASSISTANT-ADJUTANT GENERAL,

Department of Dakota, Saint Paul, Minn.

CAMP MOUTH OF GLENDIVE CREEK,

October 12, 1876.

SIR : In compliance with the verbal orders of

the commanding officer, I have the honor to report that on the

morning of the 10th instant, I started

for Tongue River with a train of ninety-four wagons and one

ambulance, escorted by four companies of infantry, strength as

follows:

Company C, Seventeenth United States

Infantry.............................................. 39

Company H, Twenty-second United States

Infantry................Strength not stated.

Company G, Twenty-second United States

Infantry.................Strength not stated.

Company K, Twenty-second United States

Infantry................Strength not stated.

That I moved from camp at the mouth of Glendive Creek at

half-past ten in the morning. So soon as the head of my train

appeared on the hills,

on the west side of the camp, I saw a signal fire spring up on

the opposite bank of the Yellowstone River, some ten miles above

and opposite the camp

I intended to make that evening. I arrived in camp—what is

called Fourteen-mile Camp—about five in the evening. The

camp is in the bed of the creek

and Commanded by hills at short range on all sides but the south,

where it is open toward the Yellowstone, there is a good deal of

brush and some timber

along the banks of the creek. The corrals were made as compactly

as possible for the night and secured with ropes. The companies

were camped close

to them, two on each side. Thirty-six men and four

noncommissioned officers were detailed for guard. Two reserves

were formed and placed on the flanks

not protected by the companies. At 3 o'clock a. m. of the 11th

the Indians made an attack on camp accompanied by yells and a hot

fire, from a ravine

about two hundred yards away. The fire was entirely directed on

the corral and they had the range exactly. This fire excited the

mules so that they

broke the ropes of the corrals and stampeded, falling into the

hands of the Indians; forty-one from the government train and six

from the railroad.

One mule was shot through. The firing continued for about half an

hour, when the Indians moved off, not only the party who had done

the firing but

another party on the other side of the camp, who had not fired,

but who were heard to move off.

At six I prepared to move forward. The road

here for about three miles runs up the bed of the creek camped

on, and there are a number of cross ravines.

After the train started, but before the rear guard had left camp,

they were fired upon from the timber skirting the creek, and a

large body of Indians,

estimated at from two to three hundred, came over the foot-hills

between the camp and the Yellowstone River, on the east side of

camp.

These Indians engaged the rear guard, commanded by Captain

McArthur, Seventeenth Infantry, at long range and kept up a

continual skirmish, firing out

of all the depressions, in the ground and from behind the crests

of hills. This forced me to move at a snail's pace, so as to keep

the train closed up,

and that the rear guard should not be left too far behind. As

soon as I reached the high prairie, I could see large numbers of

Indians on my left coming up

apparently from the Yellowstone River, and passing to my front;

these were entirely distinct and in addition to those in my rear.

My impression was

that they intended to attack me at the next water. Clear Creek,

eight miles from my camp of the night of 10th instant. Clear

Creek is a deep ravine,

very bad to get down to, and hard to pull up out of; it is so

narrow that the hills on either side will command its entire

width. At half-past 11 a. m.,

I had gotten within about half a mile of Clear Creek. My rear was

still fired on, and Indians could be seen on all sides. I sent my

wagon-master ahead

to examine Clear Creek, if possible; he came back and reported

that he saw twelve in the ravine through which he would be

obliged to descend,

and that he had heard firing on the creek itself and believed

they were in force there. I at once decided that in the crippled

condition of the train

it would be best to return to the camp at the mouth of Glendive

Creek. My reasons were these. So far the Indians had shown a

force, as near as I could estimate,

of from four to six hundred; their signal fires were springing up

in all directions. I was satisfied that if I took the train into

the bed of Clear Creek,

that it would be attacked, and be so much further crippled as to

necessitate the abandonment of some of the wagons. That the same

performance

would take place at the next creek and in all probability in much

larger force, if I were not compelled to camp away from both wood

and water.

That with the force I had I could not cover the herd in its

necessary grazing, that in going forward I should lose the major

part of the train,

and finally that if I turned at once I could take the train back

to the supply camp in safety. I at once turned back up Clear

Creek to reach the upper trail,

and reached it in about two miles. This trail is on high open

ground, and there are no intersecting ravines, so that it gave me

all the advantage in moving.

So soon as I reached the new trail, the attack in my rear ceased,

although the Indians followed me at some distance and could be

seen in small parties

till late in the afternoon. I had no further trouble with them,

and reached camp at 9 p. m., after a hard march of 29 miles. In

closing I wish to state

that it is my belief that a much larger force than four companies

of about forty men each will be required to force the train

through.

That it should be supplied with a force of at least twenty-four

good mounted men, plenty of water kegs kept constantly filled,

and not used from

except in case of real necessity, and at least one gun—two

would be better.

In reply to the signal fires, I saw a dense

smoke arise apparently in the little Missouri country about the

head of Beaver, and believe that one of their many camps

with their families is in that section of country, and that there

is a camp somewhere about O'Fallon Creek for the purpose of

annoying trains.

The men and officers did, all of them, exceedingly well, and it

is due to them that the train came off as well as it did. The

wagon-masters were the only men

that I had available as scouts, and were invaluable to me in that

capacity in looking over the country in my front.

Very respectfully, your obedient servant,

CHARLES W. MINER, Captain Twenty-second Infantry. POST ADJUTANT.

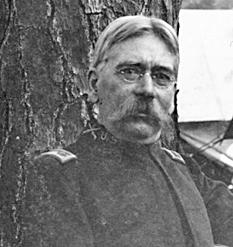

Captain Charles W. Miner, who wrote the above report

Photo from U.S. Army Military History

Institute, Carlisle, PA

RG40S W. W. Dinwiddie Coll. 312 via Dave Eckroth and

Howard Boggess

HEADQUARTERS BATTALION TWENTY-SECOND INFANTRY,

Station near Glendive Creek, Montana, October 27, 1876.

SIR: I have the honor to report that, as

communicated in my letter of the 13th instant to the headquarters

of the department, I commenced the trip

to Tongue River with the supply-train upon the morning of the

14th instant. Forty-one of the citizen teamsters, having become

too greatly demoralized

to continue service upon the road, were discharged and the

necessary places filled with enlisted men. The train consisted of

eighty-six wagons

and the escort of Companies C and G, Seventeenth Infantry, and G,

H, and K, Twenty second Infantry. Details were made from these

companies

and left behind with Captain Clarke, commanding Company I,

Twenty-second Infantry, who was directed to remain at Glendive;

and his command,

thus re-enforced, consisted of four officers and ninety-seven

enlisted men. The train escort consisted of eleven commissioned

officers (myself included)

and one hundred and eighty-five enlisted men. We proceeded the

first day 12 miles and encamped upon the broad bottom of the

Yellowstone River,

without discovering a sign of the presence of the Indians. During

the night a small thieving party was fired upon by the picket,

but the party escaped,

leaving behind a single pony with its trappings, which was

killed. At dawn of day upon the 15th the train pulled out in two

strings and proceeded quietly

to Spring Creek, distant from camp about three miles. Then I

directed two mounted men (Scout Robert Jackson and Sergeant

Kelly, Company F,

Twenty-second Infantry) to station themselves upon a hill beyond

the creek and watch carefully the surrounding country until the

train should pass through the defile.

The men advanced at swift pace in the proper direction, and, when

within 50 yards of the designated spot, they received a volley

from a number

of concealed Indians, when suddenly men and Indians came leaping

down the bluff. The men escaped without injury to person,

although their clothing was

riddled with bullets. I quickly advanced a thin skirmish-line to

the bluffs, which drove out forty or fifty Indians, and, making a

similar movement on the

opposite flank, the train passed through the gorge and gained the

high table-land. Here three or four scouts, sent out by Colonel

Miles from Tongue River,

joined us. They had been driven into the timber on the previous

evening, then corraled; had lost their horses and one of their

number, and escaped

to the bluffs under cover of the darkness. The dead scout was

found and buried. The train proceeded quietly along the level

prairie, surrounded by

the skirmish-line, and the Indians were coming thick and fast

from the direction of Cabin Creek; but few shots were exchanged

and both parties were preparing

for the struggle, which it was evident would take place at the

deep and broken ravine of Clear Creek, through which the train

must pass.

We cautiously entered the ravine, and from one hundred and fifty

to two hundred Indians had gained the surrounding bluffs to our

left.

Signal fires were lighted for miles around, and extended far away

on the opposite side of the Yellow-stone. The prairies to our

front were fired

and sent up vast clouds of smoke. We had no artillery and nothing

remained to do except to charge the bluffs. Company G,

Seventeenth, and Company H,

Twenty-second Infantry, were thrown forward upon the run, and

gallantly scaled the bluffs, answering the Indian yell with one

equally as barbarous

and driving back the enemy to another ridge of hills. We then

watered all the stock at the creek, took on water for the men,

and the train slowly ascended the bluffs.

The country now surrounding us was much broken, the Indians

continued to increase in numbers, surrounded the train, and the

entire escort became engaged.

The train was drawn up in four strings and the entire escort

enveloped it by a thin skirmish-line. In that formation we

advanced, the Indians pressing every point,

especially the rear, which was only enabled to follow by charging

the enemy and then retreating rapidly toward the train, taking

advantage of the knolls and ridges

in its course. The flanks were advanced about a thousand yards,

and the road was opened in the front by repeated charges. In this

manner we advanced

several miles and then halted for the night upon a depression of

the high prairie, the escort holding the surrounding ridge. The

Indians had now attempted

every artifice. They had pressed every point of the line; had run

their fires through the train, which we were compelled to cross

with great rapidity;

had endeavored to approach under the cover of the smoke when they

found themselves overmatched by the officers and men, who, taking

advantage

of the cover, moved forward and took them at close range. They

had met with considerable loss; a good number of their saddles

were emptied and

several ponies wounded. Their firing was wild in the extreme, and

I should consider them the poorest of marksmen. For several hours

they kept up a brisk fire

and wounded but three or four men, two but slightly, and one,

Private Donohue, of Company G, Twenty-second Infantry, whom I was

compelled to leave

at Tongue River, but who will ultimately recover.

Upon the morning of the 16th the train pulled

out in four strings and we took up the advance, formed as upon

the previous day. Many Indians occupied

the surrounding hills, and soon a runner approached and left a

communication upon a distant hill. It was brought in by the scout

Jackson, and read as follows:

" YELLOWSTONE.

" I want to know what you are doing traveling on this road.

You scare all the buffalo away. I want to hunt on the place. I

want you to turn back from here.

If you don't, I will fight you again. I want you to leave what

you have got here, and turn back from here.

"I am your friend,

"SITTING BULL."

" I mean all the rations you have got, and some powder. Wish

you would write as soon as you can."

I directed the scout Jackson to inform the

Indians that I had nothing to say in reply, except that we

intended to take the train through to Tongue River,

and that we should be pleased to accommodate them at any time

with a fight. The train continued to proceed, and about eight

o'clock the Indians again

began to gather for battle. We passed through the long narrow

gorge near Bad Route Creek, exchanging but few shots and soon

reached the creek,

when we again watered the stock and took on wood and water,

consuming in this labor about an hour's time. When we had pulled

up the gentle ascent,

the Indians had again surrounded us, but the lesson of the

previous day taught them to keep at long range, and there was but

little firing by either party.

I counted one hundred and fifty Indians in our rear, and from

their movements and positions, I judged their numbers to be

between three and five hundred.

After proceeding a short distance a flag of truce appeared on the

left flank borne by two Indians, whom I directed to be allowed to

enter the lines.

They proved to be Indian scouts from Standing Rock agency,

bearing dispatches from Lieutenant-Colonel Carlin, of the

Seventeenth Infantry,

stating that they had been sent out to find Sitting Bull, and to

endeavor to influence him to proceed to some military post and

treat for peace.

These scouts informed me that they had that morning reached the

camp of Sitting Bull and Man-afraid-of-his-horses, near the mouth

of Cabin Creek;

that they had talked with Sitting Bull, who wished to see me

outside the lines. I declined the invitation, but professed a

willingness to see Sitting Bull

within my own lines. The scouts left me and soon returned with

three principal soldiers of Sitting Bull, the last-named

individual being unwilling

to trust his person within our reach. The chiefs said that their

people were very angry because our trains were driving away the

buffalo from

their hunting grounds; that they were hungry and without

ammunition, and that they especially wished to obtain the latter;

that they were tired of the war

and desired to conclude a peace. I informed them that I could not

give them ammunition; that had they saved the amount already

wasted upon the train

it would have sufficed them for hunting purposes for a long time;

that I had no authority to treat with them upon any terms

whatever; but that they were

at liberty to visit Tongue River and there make known conditions.

They wished to know what assurance I could give them of their

safety should they

visit that place, and I replied that I could give them nothing

but the word of an officer. They then wished rations for their

people, promising to proceed to

Fort Peck immediately, and from there to Tongue River. I declined

to give them the rations, but finally offered them, as a present,

one hundred and fifty pounds

of hard bread and two sides of bacon, which they gladly accepted.

The train moved on, and the Indians fell to the rear. Upon the

following day I saw

a number of them from Cedar Creek, far away to the right, and

after that time they disappeared entirely. Upon the evening of

the 18th, I met Colonel Miles,

encamped with his entire regiment on Custer Creek. Alarmed for

the safety of the train, he had set out from Tongue River upon

the previous day.

I told him of the situation of affairs, and informed him that be

would find the Indian camp either about the mouth of Cabin Creek

or far away on his left,

traveling in the direction of Fort Peck. He concluded to go on to

Cherry Creek and there await my return from Tongue River, but

having reached that point

he found the Indians engaged in hunting the large bands of

buffalo which were roaming between that and Cedar Creek. His

future operations I believe

he has fully reported, and forwarded his dispatches by couriers.

I returned to this station with the train yesterday, the 26th

instant, having consumed

thirteen days in making the journey. The train was returned

richer by two mules and two horses than when it started out, and

suffered no loss.

In concluding this report I cannot speak too highly of the

conduct of both officers and men. The officers obeyed

instructions with alacrity,

and executed their orders with great efficiency. They fought the

enemy twelve hours and fired during that time upwards of seven

thousand rounds

of ammunition. They defeated a strong enemy, estimated by many at

from seven to eight hundred, which had defiantly placed himself

across our trail

with the deliberate purpose of capturing the train, and gave him

a lesson which he will heed and never forget. I was ably assisted

by Lieut. O. M. Smith,

my only staff officer. All other officers were serving with the

companies and furnished to their men examples of fearless

exposure and great endurance.

Very respectfully, your obedient servant,

E. S. OTIS,

Lieutenant-Colonel Twenty-second Infantry, Commanding. ASSISTANT

ADJUTANT-GENERAL,

Headquarters Department of Dakota, Saint Paul, Minn.

**********************

Home | Photos | Battles & History | Current |

Rosters & Reports | Medal of Honor | Killed

in Action |

Personnel Locator | Commanders | Station

List | Campaigns |

Honors | Insignia & Memorabilia | 4-42

Artillery | Taps |

What's New | Editorial | Links |