![]() 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry

1st Battalion 22nd Infantry ![]()

The 22nd Infantry 1874-1878

In July, 1874, the 22nd Infantry changed

stations with the First Infantry. Regimental Headquarters and

Companies D, F and H took station

at Fort Wayne, Michigan; Company A, at Madison Barracks, New

York; Companies B and K, at Fort Porter, New York;

C and G, Fort Brady; E, Fort Mackinac; I, Fort Gratiot, Michigan.

The advantages of garrison life and duties were not to last long,

however,

for on September 16, Companies A, B, D, F, H, I and K were

directed by telegraphic orders to proceed to New Orleans,

where an organization known as the White League had caused some

fear and concern as to the safety of that locality.

The Companies were packed and ready to start by midnight, and

took the train early on the morning of the 17th,

reaching New Orleans on the night of the 20th. It had been

intimated that the duty would be of ten days' duration,

instead of which it lasted eight months, until May, 1875, the

battalion quartering from time to time in various parts of the

city

and at Greenville, one of its suburbs. Companies A and K were for

a time at Jackson Barracks.

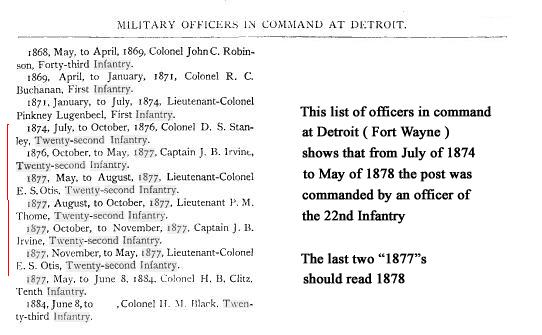

(Ed., The above list shows officers

from the 22nd Infantry being officially in command at Fort Wayne.

Note that officers could be away from that command, as in : on

campaign with their troops,

on leave, etc., and still be officially in command at Ft Wayne.)

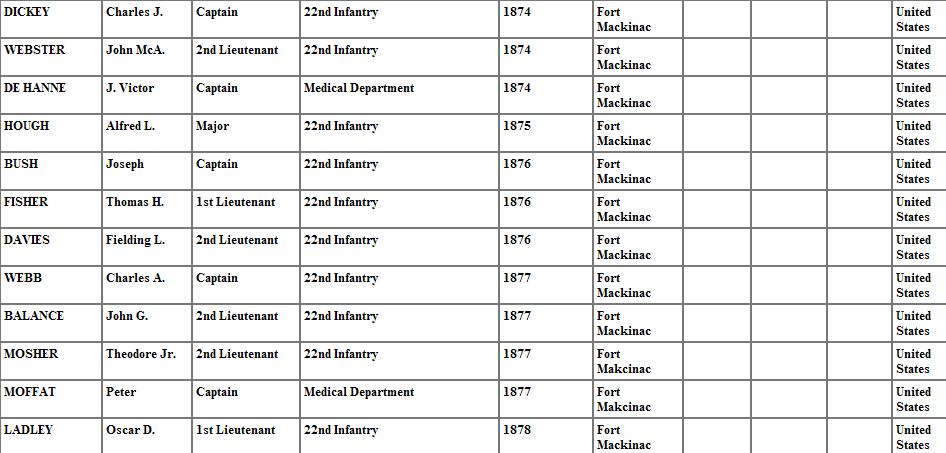

The above chart shows 22nd Infantry

officers who were stationed

at Fort Mackinac, Michigan, from 1874 to 1878. (John G.

Ballance's name is mis-spelled.)

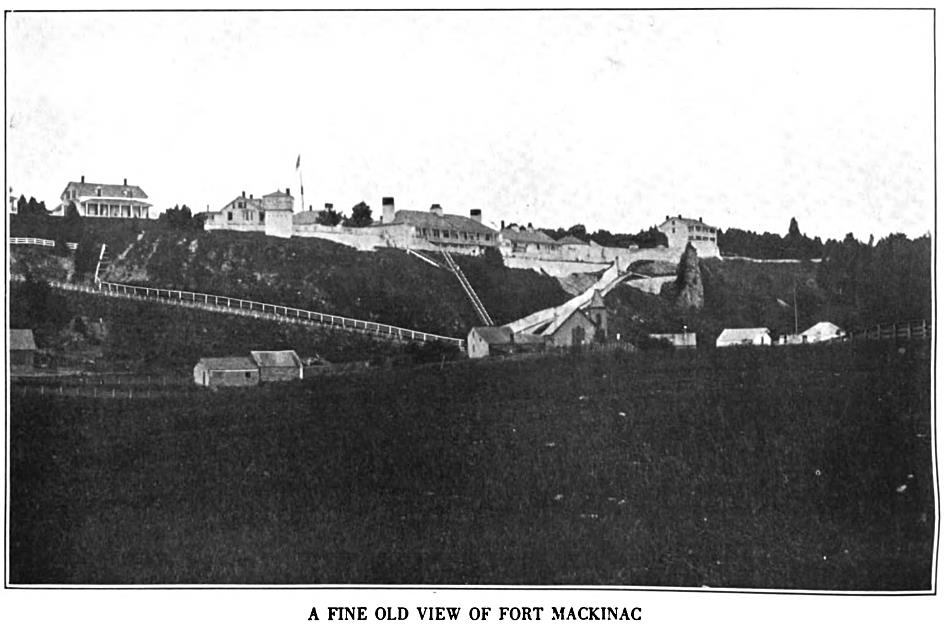

Photo from:

Historic Mackinac by Edwin O. Wood

NEW YORK THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 1918

**********************

In July, 1876, the now famed Custer Massacre

was the cause of again sending the 22nd Infantry into the field,

and on July 11,

less Company A, the same command left Fort Wayne to join General

Terry at the mouth of the Rosebud River in Montana.

Companies E, F, G, H, I and K, under Lieut.-Colonel E. S. Otis,

represented the regiment and were conveyed by the steamboat

Carroll

to General Terry's mobilization point. Hostile Indians were

encountered on several occasions, notably at the mouth of the

Powder River,

where a formidable force was encountered and only driven off

after a stubborn fight.

On July 29, when the boat

was passing the mouth of the Powder River, the Indians in large

number from the right bank

of the Yellowstone made a vigorous attack upon it. The troops

responded promptly, and the boat was landed

and two or three Companies sent on shore. The fight lasted some

time, engaged in by the troops on the boat as well

as those on shore, until the Indians were driven back into the

hills, with what loss we never knew.

Their camp was taken possession of and burned, a few firearms and

other trophies being found and taken on the boat.

There were two or three soldiers slightly wounded.

On August 1, the battalion arrived at General Terry's camp, where

it remained until the 7th. The next day it marched

with General Terry's command up the Rosebud. The valley of the

lower Rosebud is very rough and the marches

were short and difficult. In the forenoon of the 10th there was

great excitement, as a heavy dust was seen

rising some two or three miles in our front and horsemen riding

around. Reports went down the line

that we were approaching the hostiles, and an engagement was

expected within a few minutes........ 1

( Ed., the horsemen turned out to be Buffalo Bill Cody and his scouts.)

On the 10th William F. Cody, familiarly known

as "Buffalo Bill", was encountered with his detachment

of Indian Scouts.

Cody informed General Terry that he might expect to meet a force

under Crook within a few hours, and, in fact,

a junction of the two columns was effected that night.

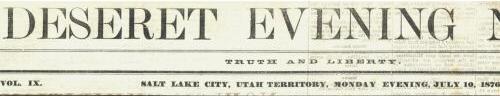

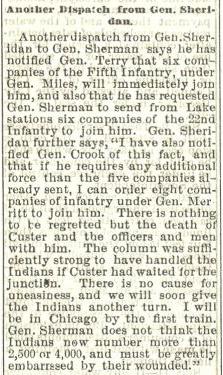

An article from the Deseret Evening

News, of Salt Lake City, Utah, published on July 10, 1876,

noting that six companies of the 22nd Infantry

had been requested by General Sheridan to join General Terry's

forces,

already on campaign in the Little Big Horn area.

The campaign which followed provided little in

the way of combat. Constant marching, scouting and bivouacking

under disheartening conditions failed to reveal a fighting force

of the Indians, and on August 31 the entire command

was concentrated at the mouth of Glendive Creek and the campaign

was discontinued.

Accompanied by two units of the 17th Infantry, the 22nd remained

in Montana most of the winter, their duties being limited

to providing escorts for wagon trains to the camp near Fort

Keogh. At Spring Creek, at three o'clock on the morning

of October 11, 1876, one of these escorts, composed of Companies

G, H and K, 22nd Infantry, and Company C of the 17th,

was attacked by Indians in force. The attack was repulsed, but

the Indians succeeded in stampeding many of the expedition's

animals,

mostly mules, and thereby so crippled the transportation that the

command was compelled to return to Glendive.

On October 14, Colonel Otis again set out with the same units,

reinforced by Company G, 17th Infantry. The Indians again

attacked in force

on the morning of the 15th, but the train was well protected and

the attacking force accomplished nothing. Several soldiers were

wounded,

but none killed. Private Donahue, Company G, who was wounded July

29, was again wounded in this fight. An amusing communication

was received by Colonel Otis the following day, written by a

half-breed said to have been well known to the troops. The letter

is quoted in full:

"YELLOWSTONE.

"I want to know what you are doing travelling on this road.

You scare all the buffalo away. I want to hunt on the place.

I want you to turn back from here. If you don't I'll fight you

again. I want you to leave what you have got here, and turn back

from here.

I am your friend,

SITTING BULL.

"I mean all the rations you have got and some powder. Wish

you would write as soon as you can."

Colonel Otis replied that he would be pleased

to accommodate Sitting Bull's force with a fight, but that he had

to take his train on to Tongue River.

On further consideration the Indians decided not to press

matters, and no further action took place. Colonel Otis, in his

official report

of the fight of October 15, highly commends the officers and men

of his command for their untiring and efficient performance of

duty.

In December, 1876, Companies E and F, 22nd

Infantry, formed part of General Miles' expedition against the

Indians under Sitting Bull

and Crazy Horse in the Big Horn Mountains. This expedition

campaigned under the greatest hardships, due to the excessively

cold weather

and heavy snowfalls. The two companies returned to Tongue River

on January 18, 1877. Two months later Companies E and F were

joined

by Companies G and H at that station. During the campaigns of

1876 some few casualties occurred in the regiment, notably the

death

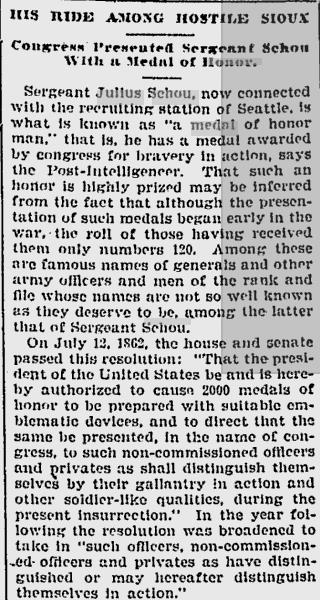

from wounds of Private Bernard McCann, Company F; Corporal (later

Sergeant) Julius Schou, Company I, 22nd Infantry, was awarded

a Medal of Honor for distinguished conduct during the campaign of

1876 against the Sioux Indians, in carrying a dispatch to Fort

Buford,

Dakota, and safely delivering it to the Post Commander.

Julius Schou Photo by Nathan Zimbrich |

Medal of Honor Citation: SCHOU, JULIUS Julius Schou was born July 17,

1849 at Copenhagen, Denmark. Julius Schou is buried in Section 17 at Arlington Cemetery. |

|

( Ed., Corporal Julius Schou's Medal of Honor

Citation states that he was awarded the Medal for actions in

1870.

However, the Regimental history indicates it was for the

campaigns of 1876. Schou did not actually receive his Medal until

1884.

Later volumes of the Army Register corrected the date to read

1876, however, several official accounts of the Medal of Honor

citation

still include this 1870 date.)

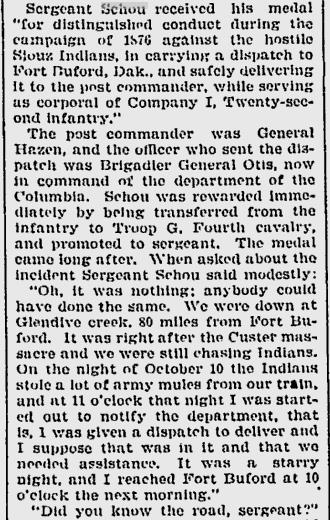

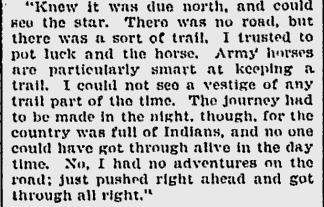

The following article from The Spokesman-Review

newspaper from Spokane, Washington, edition of March 18, 1896,

gives the story of Julius Schou's Medal of Honor action:

**********************

The Battle of Wolf Mountain

Ed., By the end of August 1876

the huge gathering of Sioux and Cheyenne who had defeated Custer

at the Battle of the Little Bighorn

had mostly broken up into individual tribes and factions, and the

Army discontinued General Terry's campaign against them.

As the Indians scattered into semi-permanent camps to hold up

against the harsh Dakota winter, Terry's column was also

ordered to do the same. Colonel Nelson Miles, in command of the

5th Infantry, was directed to build a post near the junction

of the Tongue and Yellowstone rivers where it was expected he and

his command would wait out the winter months.

On November 8, 1878 this post would be officially named Fort

Keogh.

Miles welcomed the opportunity

to be independent from Terry and believed his smaller command

could be effective against

the nomadic hostile tribes. In addition to his twelve companies

of the 5th Infantry, Miles secured the transfer to his command

of six companies of the 22nd Infantry and two companies of the

17th Infantry. During October and November of 1876

Miles 's troops continually harrassed Sitting Bull's band and

after three sizeable engagements with that band, had managed

to inflict enough losses in food, shelter and supplies upon them

as to render them ineffective as a fighting force.

|

Private, 22nd Infantry,

1876-77 Dressed for Nelson Miles' winter campaign Illustration by Richard Hook From the book: US Infantry in the Indian Wars 1865-91 By Ron Field, Osprey Publishing Ltd. 2007 |

By December the largest band of

hostiles who refused to return to the reservations was led by

Crazy Horse,

encamped along the Tongue River Valley. The winter had come early

and was extremely brutal. Game was scarce and food supplies

were dwindling, and, as survivors of engagements with the Army

and other tribes joined Crazy Horse, he became reluctantly

convinced that it was necessary to negotiate some kind of peace

terms with his enemies. A delegation was sent to ask Miles for

peace terms.

As five Sioux

headmen from Crazy Horse's village advanced on the post to

ascertain chances for a peaceful settlement

of the conflict, they were suddenly attacked by the Army's Crow

Indian scouts. All the Sioux were killed before soldiers

rushing from the garrison could save them. The episode ruined any

prospect for a peaceful outcome to the war. 2

Ed., As revenge for the

killings, Crazy Horse sent a party of 100 warriors to attack

Miles' post as a decoy, in an attempt to draw the soldiers out,

with the idea of leading them into a trap which could be set to

inflict upon them a high number of casualties.

Although Miles had not

planned to conduct another winter campaign after defeating

Sitting Bull, within days of the killings

the decoy party's retaliatory strikes demonstrated to Miles that

a campaign would have to be organized and sent into the field

that winter.

On December 18 warriors attacked government mail contractors

within miles of the post and made off with the mail and

several government animals, forcing cancellation of mail service

to the post. On December 20, 1876, the commander wired

department headquarters in St. Paul, Minnesota, to declare his

intentions. On December 26 the decoy party struck again

less than a mile from the post, stealing nearly two hundred fifty

head of cattle from the post's beef contractor and driving them

into the interior of the Tongue River Valley. Miles dispatched E

and F Company, Twenty-second Infantry, and K Company,

Fifth Infantry, under the command of Captain Charles Dickey to

pick up the Indians' trail while he finalized preparations for

his campaign.

On December 28, 1876,

Colonel Miles led the balance of his strike force away from

Cantonment Tongue River. Joining the three units

already in the field were companies A, C, D, and E, Fifth

Infantry; a detachment of forty mounted infantrymen drawn from

several companies;

five white and three Indian scouts; and the campaign's supply

train, 436 men in all. Miles also brought along two pieces of

field artillery-

a twelve-pound Napoleon cannon and a Rodman gun, a three-inch

ordinance rifle that he hid under canvas-covered wagon bows.

As the column began its

march, it was clear to all that nature would prove as much an

adversary as the warriors. Temperatures dropped

to thirty degrees below zero, and ten inches of fresh snow

greeted the troops that morning. Clad in overcoats made of

buffalo robes-which were worn

over numerous other layers of clothing-the company looked,

according to their commanding officer, more like arctic explorers

than soldiers.

With his command united,

Miles followed the Indians' trail southwest through the Tongue

River Valley for the next several days.

Fighting harsh winds, bitter subzero temperatures, deep snows,

and frequent river crossings, the strike force advanced as fast

as possible

up the river. It was a grueling march. At the more than one

hundred river crossings, wagons often plunged through the ice,

taking men and animals into the freezing water with them. 3

Ed., Crazy Horse's plan to

decoy the soldiers into an ambush quickly fell apart, as a

scouting party under Luther "Yellowstone" Kelly

captured

nine prisoners who were trying to make their way to the Indian

camp. This event caused the decoy party to attack the soldiers

prematurely,

which allowed Miles to position his command to repel any attack

by the larger body of hostiles. The terrain Miles had chosen for

that night's

bivouac along the Tongue River favored his defensive strategy. At

this point the landscape consisted of rolling hills ending in

open plains

at the river. A conical shaped butte on his side of the river

could be used by Miles to station a company of troops who would

have

a high ground advantage on the whole battlefield. The river here

was frozen solid and thus was not an obstacle as it could be

easily crossed.

As Crazy Horse and his 400 warriors approached, Miles sent A

Company 5th Infantry, under Captain James S. Casey, to join E and

K Companies

5th Infantry at the base of the butte. ( From 1895 to 1897 James

S. Casey would be the Colonel in command of the 22nd Infantry.)

On the other side of the butte, at the river's edge were Captain

Charles Dickey with E Company 22nd Infantry and

Lieutenant Cornelius Cusick with F Company 22nd Infantry, ready

to repel any direct attack made by the Indians across the river.

Company K 5th Infantry was sent across the river to slow down any

direct charge made by the hostiles.

|

First Lieutenant Cornelius

Charles Cusick commanded Company F 22nd Infantry He served as a 2nd LT and then

1st LT in the 132nd New York Infantry during the When the 31st Infantry was

consolidated into the 22nd Infantry in May 1869, He was promoted to 1st

Lieutenant on August 5, 1872, and Captain on January 1,

1888. |

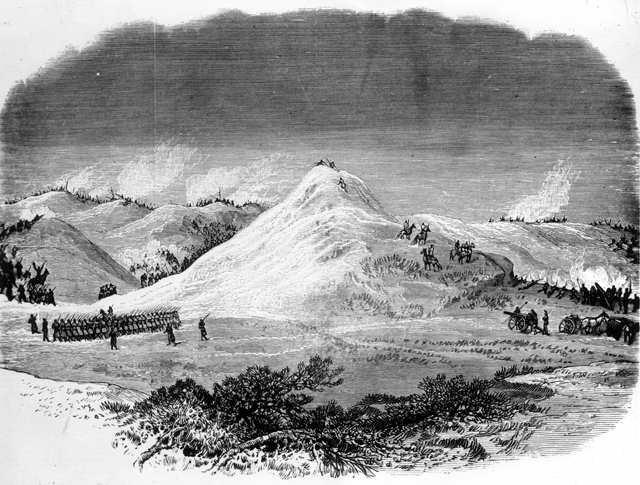

Although not drawn to scale, this illustration of the Battle of Wolf Mountain gets most of the details correct.

Illustration from the May 5, 1877 edition of Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper

In tactics usually not

associated with them, a great many of Crazy Horse's men

dismounted their horses and prepared to engage the soldiers on

foot.

At about 7 am January 8, 1877, the warriors began the attack. For

several hours the Indians repeatedly attacked Company K, but were

driven back

by rifle and artillery fire. Half the Indian force, consisting of

Cheyenne under Medicine Bear, succeeded in outflanking the

soldiers

and took positions in a series of three smaller ridges near the

butte. Captain Casey took his company in a skirmish line

and advanced upon the ridges. Company D 5th Infantry was sent to

join Captain Casey. As they fought their way up the ridges,

Company C 5th Infantry reinforced them and the three companies

pressed the attack.

When their medicine man Big Crow was cut down by soldiers'

bullets, many of the Cheyenne warriors took it as a sign of

disaster

and left the fight, leaving the Lakotas under Crazy Horse to bear

the burden of the rest of the battle. As the soldiers continued

pushing the Indians back across the ridges, Miles shifted his two

cannon upon the hostiles and this, together with the rifle fire

from the infantry

forced Crazy Horse's warriors into a covering retreat through

heavy falling snow. The cannon fire was especially effective, not

only

in a direct-fire mode, but also in high trajectory plunging-fire

into the ravines between the hills and mountains.

The two artillery pieces were handled by Lieutenant J.W. Pope of

the 5th Infantry and Lieutenant E.W. Casey of the 22nd Infantry.

After five hours of fighting, Miles' command suffered two killed

and nine wounded. One of the wounded was Private Bernard McCann,

of Company F 22nd Infantry. McCann would die of his wounds on the

return march, and for his actions during the battle

would be awarded the Medal of Honor.

The next morning Miles led

six companies across the battleground looking for enemy bodies,

but found none. Several dead horses were found,

and numerous pools of blood were also found, along with

indications that the Indian wounded had been dragged away by

their fellow warriors.

It is believed that seven Indians were killed in the fight.

However, the loss of supplies and ammunition, coupled with the

realization

that they were not safe from the soldiers even in the worst of

winter, was a demoralizing blow to the Sioux and Cheyenne.

Over the next few months huge numbers of Indians surrendered at

different agencies all across the territory.

Crazy Horse was never again able to take to the field against the

Army, and within a few months would surrender himself

to the foe against which he struggled for so long.

|

Medal of Honor Citation: McCANN, BERNARD Bernard McCann was awarded the

Medal of Honor PVT McCann's grave is located

in Custer National Cemetery, |

Medal of Honor |

On April 30, 1877, an expedition was organized

under General Miles to attack a renegade band of Indians, chiefly

Minneconjous,

led by Lame Deer. General Miles' command was composed of

Companies E, F, G, and H, 22nd Infantry, two companies of the 5th

Infantry,

and four troops of the 2nd Cavalry. The train was left on the

Tongue River, about 60 miles from the starting point, under guard

of

Company G, 22nd Infantry, and Companies E and H of the 5th.

Companies E, F, and H, 22nd Infantry, with the 2nd Cavalry

detachment,

moved up the Rosebud, and on May 7 attacked the Indians near the

mouth of Muddy Creek. The herd of 450 Indian ponies was taken

in a surprise attack by a detachment of scouts under Lieutenant

Casey. A dash by the cavalry convinced Lame Deer and Iron Star

that they must surrender in order to save themselves, but they

met with great difficulty in convincing their followers of this

necessity.

The resultant delay caused the death of both these chiefs and

fourteen of their men.

The 450 ponies provided mounts for the entire battalion of the

22nd, and the following morning, after completing the destruction

of the Indian camp,

the command started back to the Tongue River. The Indians made

one effort to recapture their ponies, but were quickly driven off

by the troops.

Following this action Company E returned to camp, Companies F, G

and H delaying their return until May 31 in order to scout in the

direction

of the Little Big Horn. May 26 Companies I and K left Glendive to

complete the consolidation of the battalion under Colonel Hough.

Almost immediately, however, Colonel Hough was detached and

ordered to Fort Mackinac, and the battalion of the 22nd Infantry

came under the command of Colonel Lazelle of the First Infantry.

Under this officer a long scout was made into the Black Hills.

The trail of Lame Deer's Indians was picked up and followed for

several days, but no action of any importance took place.

Arriving near the Indian camp at Sentinel Butts, the 22nd

Infantry was relieved, and under command of Brevet Major C. J.

Dickey,

it proceeded by marching to Fort Abraham Lincoln.

Ed., The Battle of Wolf Mountain, and then

finally, the Lame Deer Fight wrote an end to the great Sioux War

of 1876-1877.

The Battle of the Little Bighorn was the apex of the Sioux and

Cheyenne alliance, and their greatest victory. The alliance fell

apart

after that battle, and thereafter the Indians were constantly on

the defensive. Nelson Miles' winter campaign against the Sioux

and their allies cost the Indians dearly in un-replenishable

supplies and food, and denied them any respite during the

especially

harsh winter of 1876-77. Demoralized and defeated, nearly all the

tribes returned to the various Indian agencies across the

territory.

Crazy Horse surrendered in May of 1877, Sitting Bull led his

faction into Canada that same month, and the war was over.

When the command reached this post (Fort

Abraham Lincoln) news was received that the companies would

proceed to their home stations

from Duluth by boat, but the railroad riots in Chicago drew the

command to that city, where Colonel Hough again took command.

A few days later Companies A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I and K were

ordered to Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, in connection with mining

riots.

In October, 1877, the companies all returned to their proper

stations. It is of interest to note that in the preceding year

the greater part of the command had marched a little over three

thousand miles.

The Chicago Railroad Riots

Ed., The 22nd Infantry had arrived in Chicago

July 25 to assist authorities in maintaining order during the

Railroad Strike of 1877.

A mob of some 25,000 unemployed and angry workers were milling

about the city and there was worry that they may organize into

something

dangerous to life and property. The Secretary of War, George W.

McCrary anticipated that federal intervention would be necessary,

and ordered Colonel Richard C. Drum to send federal troops to

Chicago. Drum was the adjutant to General Sheridan, who was the

commander

of the Department of the Interior's Division of the Missouri, and

in Sheridan's absence Drum was de facto commander himself.

It was expected that the federal troops would be placed under

command of the governor or the mayor, to be used as they saw fit.

Although no major strikes

or riots had yet occurred in the area, and without presidential

action, McCrary directed Drum

to build up an antiriot force from six companies of the 22d

Infantry, whose 226 officers and men were at Detroit on their way

to new assignments.

Drum immediately summoned two companies into Chicago, but kept

the remaining four outside the city in reserve.

During the next two days McCrary shifted several more companies

composed of 218 officers and men of the 9th Infantry, from Omaha,

Nebraska, to the Rock Island Arsenal 150 miles southwest of

Chicago. The 9th Infantry was to provide support for the 22d,

but only if requested to do so by the Chicago mayor through the

Illinois governor or by the governor himself.

Thus far, no such requests had been received from either Mayor

Heath or Governor Shelby M. Cullom. 4

Ed., A further five companies of the 4th

Infantry and four companies of the 5th Cavalry were also sent to

Chicago.

President Rutherford B. Hayes was not consulted on the move of

Federal Troops to be used in what he considered

a job for a state government to handle, and he ordered that all

Federal Troops be directed to guard and preserve

the integrity of Federal Buildings and property only. As a

result, the federal troops took no direct part in handling any

disturbances caused by the mobs of workers; all direct action

taken against such was carried out by the police and the Illinois

militia.

However, the presence of so many federal troops around the city

was a factor of intimidation which was credited in large part

with keeping the violence which did occur to a minimum.

|

Left: Article published in the New York Times July 27, 1877 Although the President was not

consulted about the As can be seen in the article,

two Companies of the General Drum ordered the trains

bringing the troops to the city Article copyright © The New York Times |

Captain Charles J. Dickey

Photo from the MHI

Ed. : The following document, General Court

Martial Orders Number 69, of 1877 is illustrative of the harsh

life and existence

of the Infantry Soldier during the long years following the Civil

War. CPT Charles Dickey was court-martialled for being

"drunk on duty" in Chicago 25 and 26 July 1877. CPT

Dickey had been on campaign in the Indian Wars for eight years

with the 22nd Infantry, and had been breveted to the rank of

Major. He was commended for his actions at the Battle of

Wolf Mountain in January of 1877, and had participated in the

Lame Deer Fight of May 1877. Less than two months after

that fight with hostile forces, he and his command were sent to

an American city, where it was supposed they would be

utilized to confront and possibly fight with American citizens.

It is of interest to note that the railroad strikes and riots of

1877,

which began in Pennsylvania and spread to other cities, were the

first time that federal troops were utilized to put down

civil disorders in the States. One can only speculate how the

regular Soldiers of the US Army felt about such duty.

General Court Martial Orders No. 69, October 29, 1877 |

The court martial of Captain

Charles J. Dickey, Charles J. Dickey was born in

Pennsylvania and was |

The Regimental histories written

in 1904 and 1922 do not have any entries for the year 1878.

From October 1877 to approximately April 1879 the 22nd Infantry

carried out routine

garrison duties at their posts in Michigan and the eastern United

States. This period of

a little over a year and a half was the only sustained break in

the Regiment's duty on the

western frontier during the years 1866-1898.

From November 1877 to April 1879

there is only one entry in the monthly Returns of the

22nd Infantry under the heading of Record of Events. That entry

occurred in October 1878

and recorded the movement of the Regimental Headquarters and Band

to Fort Porter, New York.

Colonel David S. Stanley commanding the 22nd Infantry, His

Adjutant 1st Lieutenant Hiram C. Ketchum,

Companies B and C and the Regimental Band would remain at Fort

Porter until April 1879 when the 22nd Infantry

was once again deployed to the western frontier.

During the years 1874 to 1878

the following losses were incurred by the 22nd Infantry.

Places of birth are listed when known.

KIA = Killed In Action

DOW = Died Of Wounds

DOD = Died Of Disease

( A catch-all phrase used in the 19th Century to denote any

non-battle death)

Company B

William A. Keogh.....02/25/1874

- Private - DOD - Rhode Island - Died of inflammation of the

lungs

Edward Kennedy.....09/19/1877 - Private - DOD - Waterford,

Ireland - Died of gunshot wound self inflicted

Company D

Timothy Driscoll.....10/30/1875 - Private - DOD - Cork, Ireland - Drowned

Company F

Bernard McCann.....01/12/1877 - Private - DOW - Ireland - Died of wounds received in Battle of Wolf Mountain awarded Medal of Honor

Company G

James A. Tomkiel.....08/19/1874

- Musician - DOD - Island of Corfu - Drowned

Henry Manuel.....05/30/1875 - Private - DOD - Dorset, England -

Died of aneurism at Fort Brady, Michigan

George Bowen.....09/29/1875 - Private - DOD - Middleport, New

York - Suicide

Band

Adolf Bergmann.....05/08/1875 - Private - DOD - Baden, Germany - Drowned

**********************

Much of the above text was taken from the Regimental History published in 1922, except:

1 From the 1904 Regimental History

2 From Battles and

Skirmishes of the Great Sioux War, 1876-1877 The

Military View

Compiled, edited and annotated by Jerome A. Greene,

Published by the University of Oklahoma Press 1993

3 From the article Nelson A.

Miles, Crazy Horse, and the Battle of Wolf Mountains by

Jeffrey V. Pearson

printed in Montana The Magazine of Western History, 2001

4 The Role of Federal Military

Forces in Domestic Disorders, 1877-1945 By Clayton David

Laurie,

Ronald H. Cole, Published by Center of Military History, U.S.

Army, 1997

Additional material added by the website editor

Additional information taken from:

Returns from Regular Army Infantry

Regiments, June 1821–December 1916. NARA

microfilm publication M665

National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

Home | Photos | Battles & History | Current |

Rosters & Reports | Medal of Honor | Killed

in Action |

Personnel Locator | Commanders | Station

List | Campaigns |

Honors | Insignia & Memorabilia | 4-42

Artillery | Taps |

What's New | Editorial | Links |