![]() 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry

1st Battalion 22nd Infantry ![]()

Regimental History 1898 Part One

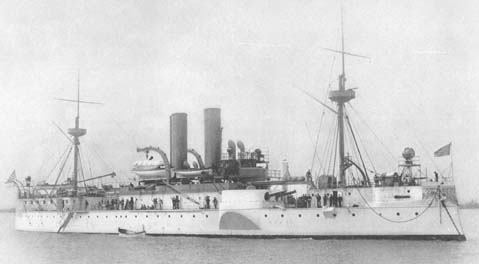

The battleship USS Maine

THE SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR - El Caney and Santiago

The approach of the war with Spain in 1898

found the 22nd Infantry in ideal condition for taking the field

against an enemy.

Like all other regular regiments of this period, the 22nd had

been brought to a high state of efficiency

both in respect to organization and equipment. Its effective

strength at the beginning of the war was thirty-five officers and

five hundred and nine enlisted men.

Most of the non-commissioned officers and many of the privates

were men of long service—the regular troops,

organized into the 5th army corps and constituting almost

entirely the force sent against the Spanish forces at Santiago,

Cuba,

formed the finest and the most effective army of its size ever

organized into one command.

With the news, on February 23, 1898, of the destruction of the

battleship Maine in Havana harbor,

came the settled belief that war with Spain was inevitable.

Preparations were quietly begun and on Saturday evening, April

15,

definite instructions were received relative to the movement of

the regiment closer to the field of active operations.

April 18, in compliance with orders from Headquarters, Department

of the Missouri, dated April 15, the regiment entrained at Fort

Crook

for Mobile, Alabama. Twenty-nine officers * and four hundred and

eighty enlisted men constituted the command.

That the people were solidly behind the approaching war was

continuously evidenced during the journey to Mobile.

At every stop enthusiastic citizens greeted the regiment with

brass bands and cheers. The entry into the Southern States

was like a triumphal procession. The train was loaded with

flowers and the engine was almost hidden under banks of blossoms.

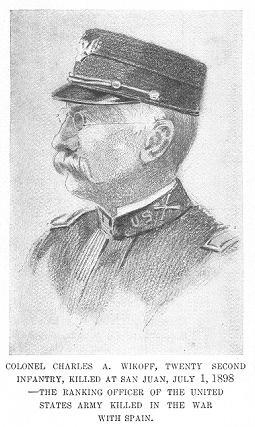

* Colonel C. A. Wikoff, commanding regiment;

Lieutenant Colonel J. H. Patterson, Major W. M. Van Home,

1st Lieutenant Herman Hall, adjutant; 1st Lieutenant J. F. Kreps,

quartermaster; Chaplain E. H. FitzGerald. regimental chaplain;

Captains B. C. Lockwood, W. H. Kell, Theodore Mosher A. C.

Sharpe, J. J. Crittenden, R. N. Getty, and F. B. Jones;

1st Lieutenants E. O. C. Ord, H. C. Hodges, Jr., G. H. Patten, T.

W. Moore, W. M. Swaine, G. J. Godfrey, W. L. Taylor, and H. L.

Jackson;

2nd Lieutenants A. C. Dalton, W. H. Wassell, P. W. Davison, O. R.

Wolfe, Harry Clement, D. S. Stanley, Jr., Isaac Newell, and F. W.

Lewis.

A Soldier saying goodbye to his wife as

he leaves for war.

Such staged, emotional, patriotic themes in photos were very

popular in 1898.

The regiment went into camp near

Mobile April 20. |

From a stereoview entitled: |

May 4, 1st Lieutenant Wilson Chase joined the

regiment from detached service on college duty.

On May 6, the regiment was transferred to the 1st Brigade,

Infantry Division.

May 14, 1st Lieutenant H. C. Hodges, Jr., left the regiment on

special recruiting duty at Fort McPherson, Ga.

May 23, 2nd Lieutenant D. L. Stone, recently graduated from West

Point, joined the regiment.

On May 25, the regiment was finally assigned to the 1st Brigade,

2nd Division, 5th Army Corps.

May 26, Captain A. C. Sharpe left the regiment on detached

service as adjutant general, 1st division, 5th army corps.

June 1st, Captain W. H. Kell left the regiment

on detached service as adjutant general, 1st brigade, 2nd

division, 5th army corps.

June 3, 2nd Lieutenant P. W. Davison was detailed brigade

commissary, 1st brigade, 2nd division, 5th army corps.

Lieut. Davison remained on duty with troops throughout the

campaign.

June 7, the regiment broke camp and proceeded

by rail to Port Tampa, Florida, arriving there at 1 p. m.

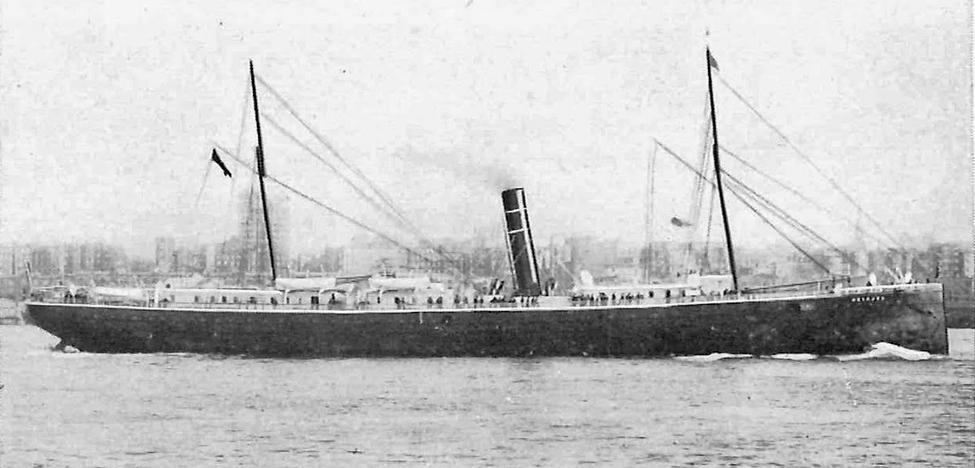

The same night it went aboard the transport Orizaba, No.

24. The Orizaba dropped anchor in the bay and remained

there until 8 A. M.,

June 14, when the 5th Army Corps started on its expedition

against Santiago de Cuba. At this period the enlisted strength of

the regiment

had been reduced to four hundred and sixty-nine, by reason of

discharges and details of various nature.

Santiago had been made the objective of the expedition because of

the fact that the Spanish fleet had been blockaded in the harbor

there,

and its capture or destruction necessitated the assistance of an

army.

The Transport Orizaba which brought

the 22nd Infantry to Cuba

The ship was 336 ft long and had a displacement of 3496 gross

tons.

For the invasion of Cuba, she carried the following consisting of

35 officers and 622 enlisted men:

2nd Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry (one battalion)

22nd U.S. Infantry from Tampa to Cuba.

4th U.S. Artillery, Batteries G and H (Siege Artillery battalion)

Photo from the Stillwater Woods webpage

June 20, Colonel Wikoff was placed in command

of the 3rd Brigade, 1st Division, 5th Army Corps,

and Lieutenant-Colonel Patterson took command of the regiment.

1st Lieutenant Wilson Chase was detached from the Regiment

and accompanied Colonel Wikoff as his aide. (Ed., Colonel Wikoff,

in his capacity as Brigade Commander, was, however,

still a Colonel of the 22nd Infantry, and still officially the

22nd Infantry Regimental Commander.)

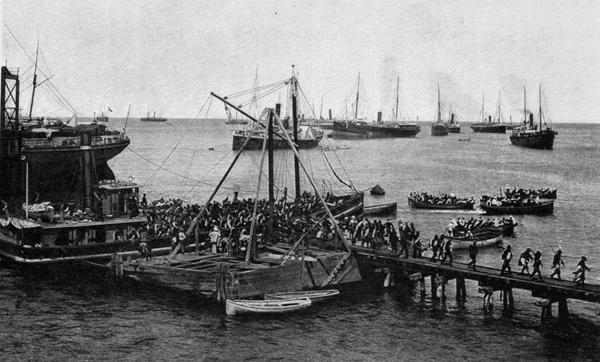

The expedition arrived off Morro Castle, at the

harbor entrance to Santiago, about noon June 20. The 2nd

Division, 5th Army Corps,

was ordered to disembark first, accompanied by the Gatling gun

detachment.

The steep and rocky coast of Cuba in the

vicinity of Santiago bay offers no good landing place.

An iron pier used for unloading ore at Daquiri, the point

selected for disembarkation, offered but slight aid in the way of

a landing place.

This pier the Spaniards had unsuccessfully attempted to destroy

by fire.

Early in the morning of the 22nd, the regiment was transferred to

small boats and towed toward the smoldering dock.

Then men showed characteristic American dash and desire for

action. As the men were unloaded from the Orizaba,

cheers burst from the decks of the nearby transports awaiting

orders to debark. Regimental bands played and shells screeched

overhead,

bursting far up on the heights as the fleet out at sea bombarded

the wooded mountains that rise from the beach.

Tugging launches puffed and whistled their way toward shore. Near

the ore pier a wall of surf roared an angry welcome

and broke into swamping torrents. Boat bumped boat as they

crowded toward the dock and were swept against the piles,

bobbing here and there until caught by a line from the land. Out

scrambled the regiment, tossing blanket rolls ahead of them,

but carefully handing rifles to helping comrades—a

surf-drenched, panting regiment, that caught its breath again

and cheered as their colors unfurled—the first on Cuban

shore.

The iron ore pier at Daiquiri, the 2nd

day of the landings,

when the sea had calmed and the troops coming ashore had an

easier time.

After a brief rest the regiment marched inland

about four miles on the road to Siboney and camped on Daquiri

creek.

June 23, the regiment was placed in advance and by noon had taken

possession of Siboney,

the Spanish force of six hundred retiring and offering no

resistance. Here the first Spanish colors taken in the campaign

were captured by men from Company B (Crittenden's) after the town

had been entered.

In Siboney the next day,

Orrin R. Wolfe of the Twenty-second Infantry found about half a

dozen locomotives in a roundhouse.

The Spanish had tried to sabotage them by destroying a vital

part, such as a driving rod, from each of them. "I knew I

had

a number of men in the company who had been railroad men,"

Wolfe reminisced. "We worked for some time, taking a part

from one engine

and putting it in the place of a part that was missing. One was

ready to go about 3:00 P.M. We only had a little water, but a

water tank

was about 200 yards down the road, so we had up steam. I was in

the cab with three or four soldiers, one acting as engineer.

I got hold of the whistle cord and proceeded to toot. We ran out

of round-house and down the track, soldiers cheering." ¹

The regiment was ordered in from outpost on

June 24, and sent to reinforce Young's brigade engaged at Las

Guasimas, four miles distant,

but did not arrive until after the action. It camped that night

near Sevilla in advance of the morning's battlefield.

The regiment moved to Sevilla on the 25th and remained in camp

there until the morning of the 27th, when it moved forward

four miles on the road to Santiago. It remained in this position

until June 30, parts of the companies on outpost at all times. '

The march toward Santiago was resumed at 4 P. M., June 30, and

that night the regiment bivouacked along the Caney road,

east of the town and in sight of the Spanish outposts.

The general plan of the Santiago campaign was to send one

division (Lawton's) against Caney; after taking the town

the division to swing to the southwest and take position on the

right of the line (two divisions) in front of Santiago.

As part of the 1st Brigade of Lawton's division the 22nd Infantry

was to occupy the roads leading from Caney to Santiago,

and cut off the Caney garrison should it attempt to escape,

At 4:30 A. M., July 1, the twenty-four officers and four hundred

and thirty-six enlisted men comprising the 22nd Infantry

marched down a trail overgrown with brush and vines until it

reached the main Santiago-Caney road near the Ducoureaux

house—

covering this road was a part of the regiment's assigned

position. The 2nd Battalion was then deployed and skirmished

northward

through the jungle to see if there were any other roads over

which the Spaniards could retreat to Santiago.

A Spanish infantry unit assumes a

defensive formation

as it moves down a Cuban road.

Meanwhile, the 1st Battalion moved rapidly

northward along the main road, until at about 1,200 yards the

advance guard, Company A,

received a sharp Mauser fire from the town. The battalion then

deployed east and west of the road. Lieutenant-Colonel Patterson,

who accompanied the 1st Battalion was severely wounded here and

Major Van Horne took command of the regiment.

For half an hour the advance was through dense undergrowth and

tangled vegetation

that prevented the battalion from seeing more than ten feet to

the front.

To keep the line the men were obliged to continually call to the

skirmishers on either side of them.

The Spanish fire, coming from a chain of intrenched blockhouses

and almost invisible rifle pits, swept the ground.

At 800 yards a clearing was reached, beyond which the battalion

caught its first glimpse of the enemy's position.

The men were ordered to lie down and take such cover as the

ground afforded.

Volleys by company and platoon were fired during the brief

moments when the enemy exposed themselves.

To husband ammunition, sharpshooters determined the range by

actual firing before volleys were fired.

General Ludlow, Brigade Commander, took position with Company A

at this period of the fighting

and from this point issued his orders during the remainder of the

day.

The battalion was advanced to 700 yards with severe losses. For

three hours it had been under heavy fire from an intrenched

and skillful enemy that had made elaborate plans to beat back an

attack from this very direction.

Meanwhile, the second battalion, the extreme

left of the line, slowly forced its way through the underbrush

for half a mile,

swung to the east, and under heavy fire from the then concealed

positions, laboriously hacked its way through the chaparral

until it found the Cuabietas road leading westward from the fated

village. Part of the regiment's assigned position was the

covering of this road.

So difficult was the advance that it was impossible to keep the

line together. Company F (Getty's) became separated

from the rest of the battalion. This company reconnoitered the

ground west of the battalion's position and after receiving the

enemy's fire

from the San Miguel blockhouse without replying to it, rejoined

the battalion at the edge of a fire-swept clearing

500 yards from the enemy's main position. As a result of this

reconnoitering, Captain Getty succeeded in cutting the Caney

telephone line

along the Cuabietas road. From noon until one o'clock there was a

lull in the firing.

Taking advantage of it, General Ludlow moved the second battalion

still farther to the west and north, advanced the first battalion

to within 500 yards of the enemy, and placed the 8th Infantry

between the first and second battalions of the 22nd Infantry.

After one o'clock the enemy renewed its fire with increased vigor

and the men of the command were compelled to hug the ground

at the edge of the clearing and watch for the scarce moments when

the enemy would expose themselves.

The heat was almost insufferable, water was almost impossible to

obtain. Any movement along the line was sure to bring a

well-directed volley

from soldiers who were veterans in bush warfare. Men lay

sweltering on the ground waiting for something to shoot at;

bullets ploughed the ground in front and threw dirt over their

sweaty faces. The regiment prayed for something more

than momentary shots at the enemy. Finally the regiment located

the intrenched blockhouses and rifle pits south of the village.

These defenses had been constructed and placed by a master hand;

they afforded the defenders almost perfect protection

and the enemy was able to sweep with their fire all parts of the

regiment's position.

Loopholes in the blockhouses and parapets of the trenches were so

sloped that unaimed fire covered the field.

From these loopholes, at short intervals came puffs of smoke and

then a hail of bullets. Occasionally the defenders stood upright

in the trenches

to fire volleys and for a brief interval the parapet appeared

dotted with straw hats. A moment later the enemy was once more

invisible.

At times a Spaniard would dart from trench to blockhouse.

Spanish soldier of the 29th Regular

Infantry Battalion.

514 soldiers of the 29th fought a tenacious defense at El Caney,

and only retreated when their ammunition ran out.

Late in the afternoon when the town was

captured, the enemy trenches were found filled with dead and

wounded.

Despite difficulties of target, the regiment shot accurately.

From due south of the town came enemy fire that remained

unanswered. Tall trees in this direction concealed the main

buildings

of the town and field glasses could discover no enemy. To return

this fire by infantry would have been a waste of ammunition.

The artillery seemed to have no effect on this position so far as

stopping the enemy's fire from this direction.

Capron's battery changed position about 2:30 o'clock and fired a

few shots at the defenses south of the town

but produced not the slightest diminution in the fire coming from

the works there.

Heat, thirst, inability to see the enemy, absolute ignorance in

regard to the damage inflicted on the Spaniards

and visible evidence of our own losses produced some

discouragement and an intense desire to meet the enemy at close

quarters.

Orders to charge the town would have met with enthusiastic

response, but the plan of battle required the regiment

to hold its exposed position covering the two roads to Santiago.

Suddenly from the stone fort east of the village came the sound

of American cheers.

The stone fort, its intrenchments cut in solid rock, had fallen.

Gallant troops, gallantly led, had cut through wire

entanglements,

charged up the hill and stormed the fort. The flag of the United

States now appeared where all morning had waved the Spanish

colors.

It was then three o'clock in the afternoon.

The larger garrison stubbornly remained in the village for an

hour and a half longer and held some of the other defensive

works,

but finally, under the destructive fire of Ludlow's brigade, was

forced to evacuate its position.

The Spaniards attempted a retreat to Santiago, choosing the

Cuabietas road. But this road was barred by the 2nd battalion of

the 22nd—

a battalion that with patience and persistence had lain all day

under heavy fire waiting for this moment.

The retreating Spaniards were met with company volleys. Quickly

the retreat was changed to a rout and the rout to a surrender.

Sixty-five prisoners and a quantity of arms and ammunition were

taken by Companies D and F.

Few, if any, of the retreating force escaped. Along the line of

their march were 186 dead and wounded,

among them the former gallant defender of Caney, General Vera del

Rey.

-----------------------------------

-----------------------------------

General Joaquin Vara del Rey Y Rubio, Commander of the Spanish at El Caney ---------------------------COL Charles Wikoff-----------------

The battle was won—but the victors had

suffered severe losses. Of the twenty-four officers of the

regiment who participated in the battle,

six had been wounded ** ; of four hundred and thirty-six enlisted

men, forty-four had been killed and wounded.*** The total loss

was nearly eleven per cent.

San Juan, too, was marked with the regiment's blood: Colonel

Wikoff was killed early in the day, while gallantly

superintending the deployment of his brigade.

** Lieutenant Colonel John H. Patterson,

Captain Theodore Mosher, Captain John J. Crittenden, Captain

Frank B. Jones,

1st Lieutenant George J. Godfrey, 2nd Lieutenant William H.

Wassell.

*** Killed:

Private Samuel Bennet, company A;

Privates Michael Gibney and Michael Werner, company B;

Private James W. Bampton, company C;

Private Gustav V. Sutter, company E;

Corporal Gebhard Young and Private Willie Brooks, company G;

Privates William L. Forrester and Peter Johnson, company H.

Wounded:

Corporal Laurence Graebing and Privates Robert

M. F. Ellingham, Henry J. Pohl, Charles A. Pound,

William Mendel, Michael Sheehy, and Gottfried Wruck, company A;

Corporal Hannan E. Newman, Musician David Olson, Wagoner Frank

Kohlert, Privates John H. Grotness and Joseph Schmitt, company B;

Sergeant Henry Janz and Private John C. F. Hill, company C;

Privates James Connaghan and George Hoover, company D;

Privates Lyndall C. Jamison, Frank W. Nelson, and George Winters,

company E;

Sergeant William Parnell, Privates Albert Field, Fred W. Lynch,

and Alet B. Strock, company F;

Sergeant John B. Senecal, Corporal Christian P. Nielsen, Wagoner

Fred Miller, Privates Elmer E. Sedam,

Casper Meither, Charles A. Osgood, and Delbert E. Hartzell,

company G;

Privates Michael A. Donohoe, James Harris, Leonard Kupfer, and

Richard Shepard, company H.

Care of the dead and wounded—our own and

those of the enemy—next demanded attention. Our dead were

buried on the field.

The wounded were carried back to a partially sheltered spot

beneath the trees where the brigade hospital had been located.

In the enemy's positions were ample proofs of the stubbornness of

their defense and the accuracy of our fire.

In one small trench were counted thirty-seven dead Spaniards.

At six o'clock in the evening, orders were received to march back

to the Ducoureaux house and thence to Santiago.

The regiment slept along the road, many without blanket rolls,

all without rations.

**********************

¹ The

Splendid Little War by Frank Freidel

Burford Books, Inc. NJ 1958

Much of the above narrative taken from the 1904 and 1922 Regimental Histories

Additional information taken from:

Returns from Regular Army Infantry

Regiments, June 1821–December 1916. NARA

microfilm publication M665

National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

Register of Enlistments in the U.S. Army, 1798-1914; (National Archives Microfilm Publication M233

Home | Photos | Battles & History | Current |

Rosters & Reports | Medal of Honor | Killed

in Action |

Personnel Locator | Commanders | Station

List | Campaigns |

Honors | Insignia & Memorabilia | 4-42

Artillery | Taps |

What's New | Editorial | Links |