San Francisco Earthquake 1906

Part Two

San Francisco City Hall and Hall of Records

City Hall was the most picturesque earthquake ruin in the city, though the Hall of Records - the dome to the right - gutted by fire, was not badly damaged. This photograph appears to have been taken from the Grant Building at the corner of Seventh and Market streets.

By the 21st the National Guard had arrived, and the city was in the hands of the U. S. Army, U. S. Navy, U. S. Marine Corps, National Guard, some 500 of the police force, and a citizens' committee, under arms to some extent. It became necessary to reduce the various organizations, all acting independently, to some concerted plan of action. A conference was held between General Funston, General Koster, commanding the National Guard, and Mayor Schmitz, and arrangements made dividing the city into certain geographical districts, six in number. These districts were afterwards changed to some extent and the final arrangement is shown on the map and will be referred to later.

On the evening of April 22, Major-General Greely returned to San Francisco and assumed command of the Pacific Division. During the period above referred to, rumors were current of many deaths by violence, of looters and citizens shot down by troops and consequent loss of life. Subsequent investigation showed nine deaths by violence: two killed by the National Guard, one by a member of a socalled citizens' vigilance committee, one by a police officer, one by a special police officer and a marine, and four deaths of unknown parties which occurred in parts of the city not occupied by the regular army. No deaths occurred by action of the regular troops.

On the 22d of April there were some 300,000 people in the city to be provided with food, shelter and clothing. On the 23d the office of the Mayor was moved to Fort Mason thus throwing the military and civil administration in close touch with each other and materially aiding in the transaction of public business. The policy of administration was defined as follows:

In matters of purely military control, including the guarding of Federal buildings and property, military orders were supreme. In regard to what were known as non-military duties, it was set forth that the army was in San Francisco for the purpose of assisting the municipal authorities to maintain order, protect property, and to organize and systematize the measures for relief of the suffering people. The army was forbidden to seize stores or vehicles or to impress labor, and was directed to refrain from interfering with private business. Authority was granted the military to make arrests for civil offences, in each case the offender to be turned over to the civil authorities. Proclamations affecting the public were jointly signed by the Commanding General and Mayor of the city. A citizens' committee had been appointed by the Mayor, consisting of fifty of San Francisco's leading citizens, irrespective of politics or party affiliations. Dr. Edward T. Devine, special representative of the Red Cross, had arrived with Mr. E. H. Harriman from New York. The Hon. Victor H. Metcalf, at that time Secretary of the Department of Commerce and Labor, also arrived from Washington. Conferences were held in which the vast interests at stake were discussed and a policy quickly outlined. Information had been received of the prompt action in Washington in forwarding tentage and designated consignees would simply create congestion that would make all deliveries impossible, and the people at large would never get their food or supplies. It was thereupon decided that there should be but one official consignee for all arriving supplies intended for relief, no matter to whom marked, and the Army was asked to assume the responsibility of this consignment. The Division Commander accepted the trust, and directed that the Depot Quarter-master take delivery of all stores intended for relief purposes.

The military authorities were also asked to take entire charge of the general distribution of relief supplies after their arrival in the city, and the Division Commander outlined the general plan in G. O. No. 18, Headquarters Pacific Division, April 29, 1906. This order provided that Major Lea Febiger, Inspector-General, take charge of the organization of relief stations; that the Depot Quartermaster assume charge of the receipt, transportation and temporary storage of all incoming supplies; that the Depot Commissary, Major C. R. Krauthoff, Subsistence Department, take charge of all food supplies after being delivered in the city and establish a delivery system to the relief stations above provided for. The importance of this work consisted in resolving the heterogeneous arriving supplies into component parts resembling a balanced ration. In the early day of supply the food products on the docks went out as they came, flour, hams, bacon, etc., first in first out, anything so long as it was food. The system provided for food depots which will be enumerated later, where the supplies were all properly separated and prepared for issue to relief stations, and docks and railroad stations were thereafter only used for transportation purposes.

Colonel G. H. Torney, Medical Department, was placed in charge of all sanitary work, both of the camps and city.

Colonel W. H. Heuer, Corps of Engineers, was charged with all duties relating to water supply. A system of military and civil districts was established to meet the various requirements. The boundary lines of these districts had been changed somewhat, but were finally and definitely fixed as shown, a total of six. The formation and extent of these districts was a matter of applied common sense as the necessities developed, the situation changing daily and hourly as the great mass of homeless, drifting humanity began to settle down in some definite locality. The extent of territory to be covered and the responsibility entailed by the assumption of the work of relief suggested more troops and more officers. After correspondence with the War Department, it was finally decided to send to San Francisco, in addition to the troops already in the city by the Department Commander's orders, 1,500 additional troops and 45 selected officers. The entire force in the city finally consisted of 1 Major-General, 1 Brigadier-General, the 1st and 14th Regiments of Cavalry, the 10th, 25th, 27th, 29th, 32d, 38th, 60th, 61st, 64th, 65th, 66th, 67th, 68th, 70th, and 105th Companies Coast Artillery; the 1st, 9th and 24th Batteries Field Artillery; the 11th Battalion Field Artillery, consisting of the 17th and 18th Mountain Batteries; the 10th, 11th, 14th, 20th and 22d Regiments of Infantry; Companies C and D, Corps of Engineers; Companies A and B, Hospital Corps; Companies A, E and H, Signal Corps, and 168 staff, detailed and retired officers. To these men were added during the earlier days a large force of the navy, a battalion of marines, and a force of naval apprentices, also the force of the National Guard, State of California.

The districts were placed under command of the senior officers in the various districts, the 1st, 2d, 3d, 5th and 6th being under command of the United States troops, the 4th district being under command of the National Guard. The police were used generally in their legitimate work throughout the city, the military in all cases making civil arrests only when absolutely required and then turning over the arrested persons to the police. The Division Commander exercised general control and directly supervised relief operations. The Department Commander directly controlled military matters pertaining to the large force under his command.

The commanding officers of districts directly controlled all military matters in their districts and exercised supervision over the various relief operations.

This brings us down to a description of the final system of relief. The Finance Committee, of which ex-Mayor Phelan was chairman, controlled all matters pertaining to finance and the millions of dollars of contributed funds, with the exception of the relief funds appropriated by Congress to be disbursed under the direction of the War Department; which funds were finally disbursed by the Depot Quarter-master under the direction of the Division Commander. A most important factor in the relief work was the organized work of the Red Cross. Dr. Devine had later been joined by Mr. Bicknell of Chicago, and the situation resulted in what amounted to a combination for the general good of the public between the prominent business and municipal men of San Francisco, the Red Cross organization, and the Army of the United States. The combination was necessary and important. To have worked independently would have defeated the entire plan¾strength lay in unity of action. Dr. Devine with his large experience as a professional relief worker threw all his energy and experience into this plan. He served with ex-Mayor Phelan on the Finance Committee and was an active and potent power, not only for active work but for harmony of interests as well. All Red Cross contributions went into the general supply and were treated accordingly.

The stores that arrived for the relief of San Francisco up to July 20 amounted to 1,702 car loads and 5 steamship loads, a total of approximately 50,000 tons. At the height of the operations about 150 car loads were delivered into the city daily, in addition to stores arriving by steamers. A conference with the General Manager of the Southern Pacific Railroad Company, Mr. Calvin, resulted in the adoption of the following plan for railroad stores: The Southern Pacific Railroad Company would undertake to deliver all arriving stores intended for relief from all sources, no matter to whom consigned, to Entry No. 1 at the Presidio dock, Entry No. 2 at Folsom street dock, and Entry No. 3 at 3d and Townsend Streets, or the general freight depot of the Southern Pacific Railroad. The Santa Fe Railroad also agreed to deliver at Entries Nos. 1 and 2 and Entry No. 4, Spear and Harrison streets, the Santa Fe general freight depot.

Possession was taken of two additional docks, Nos. 8 and 10. No. 8 was used for tents, stoves and equipage, No. 10 for forage and No. 12, or Folsom street, which was under lease by the Government, for food supplies. They were all taxed to their utmost for many days.

Captain Jesse M. Baker, Quartermaster's Department, was detailed as an assistant to the Depot Quartermaster, and stationed at Oakland Pier with two trained transportation clerks from the Depot Quartermaster's office.

Officers of the Quartermaster's Department were also stationed at Point Richmond, the Santa Fe freight yard, Entries Nos. 1, 2, 3 and 4, Quartermaster Depots Nos. 1, 2, 3 and 4. Officers of the Subsistence Department were stationed at the Food Depots, Nos. 1, 2 and 3. The various Quartermaster and Commissary Depots were connected by wire with the office of the Depot Quartermaster, which had been established in the Quartermaster Warehouse at the Presidio, and the Commissary Depots connected with the office of the Depot Commissary, which was established at Folsom street dock. Every arriving car was checked up across the bay, either at Oakland Pier or Point Richmond. Every lighter leaving for any of the entries was reported by wire to the Depot Quartermaster with the car numbers and what entry consigned to. The Depot Quartermaster could thus control the supply and balance the arrivals at the different entries, wiring orders to deliver more or less at the different points as occasions demanded. A dispatch boat was put in service, making two trips daily to Oakland Pier. At each trip, yard car slips giving complete list of cars with numbers and contents were forwarded to the main office. These were abstracted as fast as they came in and from this abstract acknowledgment of arrival was made to all donating parties in the different parts of the country. This branch of the work was most important, as Relief Committees in the various cities and towns were always desirous of obtaining information which would enable them to inform the people of their community that the stores had arrived in San Francisco and had reached the suffering people. The record also enabled satisfactory answers to be given to the hundreds of inquiries by wire and mail from all over the country on this subject. Every car load was finally accounted for and inquiries answered locating stores, except in some cases of individual packages.

The Quartermaster-General had been asked by wire to have the number of every car of military supplies reported to San Francisco by wire as soon as it was dispatched. These instructions were promptly given, and this advance information aided very greatly in preventing confusion.

The stores for Presidio were delivered by river steamers acting as lighters from cars at Oakland Pier. At Entry No. 2, or the three docks above described, deliveries were from river steamers acting as lighters and also from cars delivered alongside of the docks by floats. Entry No.3 was by cars sent across the bay on floats and delivered at the 3d and Townsend Railroad yard, which fortunately was not destroyed by fire. The small amount of freight that arrived from the south also came into this depot. Entry No. 4 was from the Santa Fe Railroad by float to the Spear and Harrison freight depot. The steamships delivered at the three docks, 8, 10 and 12. It will thus be seen that there were four avenues through which supplies could reach the city simultaneously, and by night as well as by day.

The arriving forty-five officers were detailed on arrival to take charge of various stations throughout the city. Fifteen were ultimately detailed as assistants to the Depot Quartermaster, and placed in charge of the various entries and depots, as above stated. As the various stations were established in all administrative departments, the Signal Corps with its usual prompt effectiveness connected up the stations by wire with the main offices and Department Headquarters. Operators were placed at all instruments and communications by day and night established During the first three days issues were made from the quartermaster supplies in store at the four depot ware-houses at the Presidio, which amounted to 3,000 tents (common), 12,000 shelter tents, 13,000 ponchos, 58,000 shoes, 24,000 D. B. shirts and other articles necessary to relieve immediate suffering. This issue was made in the face of necessity without any authority, but when reported was promptly approved by the Secretary of War, and was afterwards vastly increased by the stores arriving from eastern depots until the total money value reached $717,142.42. Donated clothing of all descriptions began to pour in from different sources all over the country, much of it new and in good condition, but a considerable portion worn, and some consignments simply worn-out garments that were only in the way. Wires were sent to different parts of the country notifying the various relief committees that only new and first class clothing was wanted. This clothing, when it first arrived, was in small lots and issued from the Presidio docks Folsom street dock, and 3d and Townsend depots. It soon became evident that these issues would have to be systematized along the same lines as the subsistence supplies. The contents of boxes were usually unknown and to send them out indiscriminately gave no assurance that the people would get the kind of clothing needed. The entry ports were also getting congested to an alarming extent. A hurried consultation resulted in Dr. Devine, Mr. Pollock of the Finance Committee, and the Depot Quartermaster, with the approval of the Division Commander, calling on the Board of Education, which fortunately was found in session, for space in which to start what proved to be a vast dry goods store. They gave permission to take possession of any school house or houses in the city. A fortunate selection was made of a new three-story school building at 111 Page street. This location was fairly central; the building had a large open court for opening cases of goods and had wide entrances and staircases. The building was selected on a Wednesday afternoon. Thursday morning by daylight an officer of the Quartermaster's Department, Captain J. J. Bradley, 14th Infantry, was there to take charge. Mr. Pollock found about a hundred ex-Emporium employees and had them there early Thursday morning. Thursday and Friday the dry goods cases were poured into the building, the trained employees rapidly established departments, men's clothing, women's clothing, children's clothing, blankets, shoes, etc., using empty cases for counters and shelving, and by Saturday a new free emporium was open and ready for business.

The experience of a day or two proved that another school house or store was necessary, and the Everett School was established as a branch establishment with an officer in charge, assisted by Mrs. Curtis of the Red Cross. To this store was sent all second-hand clothing, all new clothing going to 111 Page street. While the work of establishing subsistence and clothing depots was going on, a system was also being perfected making a complete system of relief sections in the various districts, each section containing a number of relief stations, each section under the direction of an officer of the army and each relief station under some person or employee designated by the Red Cross, the total number of stations being 716. This entailed a vast amount of organized and systematic relief work, as it was soon discovered that the strong and aggressive were apt to prosper at the expense of the weak and modest. A card system was organized, each of the relief stations being responsible that people pertaining to that station received their share and no more. The stations forwarded requisitions to the Chief of Sections. The Chief of Sections sent them to the depots of supply with instructions as to number of station to be delivered. The requisitions were honored at the depots and the machinery of supply worked smoothly, considering its hurried organization and the vast amount of work to be accomplished. The completed system for relief work, ncluding all supplies, is briefly as follows: Supplies entered the city through four entries, 1st, 2d, 3d and 4th, heretofore described. From these entries clothing was delivered to clothing depots 1 and 2; food supplies delivered to food depots No. 1, gun sheds Presidio, No. 2 warehouse, Spear and Harrison streets, No. 3. Moulder School, Page and Gough streets. All supplies were separated in the depots and prepared for issue, and resembled well-equipped clothing and grocery stores. The Medical Department had a medical depot at the Presidio near the General Hospital, where medical supplies were treated in like manner. Issues were made from these depots to the 716 relief stations, under approved requisitions from the Chief of Sections. Each station issued to the people within its limits, the bread line being the most conspicuous evidence of such issue.

This supply entailed a great deal of land transportation, the history of the organization of which is as follows: For the first few days the city was supplied by volunteer teams. The Quartermaster at the Presidio had some government transportation. The Depot Quartermaster had what was left of the government contract transportation. On April 23 the Post Quartermaster, Presidio, was directed to report to the Depot Quartermaster as his assistant, and the transportation was thrown into one general corral or park on the Presidio plain near the dock. Arriving wagon trains with organizations were also put under this management. All four-mule teams were broken up into two-mule teams and a large number of surplus army and escort wagons in the depot were set up and made available, thus increasing the number of available teams. Too much time was wasted in sending teams from the Presidio to the lower part of the city to attend to the hauls from Entries Nos. 2, 3 and 4, and a lot was rented near Folsom street dock and a corral established there. During this time a large amount of promiscuous city hauling was being done under direction of the municipal authorities and the Finance Committee, the teams used running into many hundreds, all under pay, or claim for pay. The Finance Committee asked that the army take over all transportation in the city for all purposes for betterment of management in systematizing under one head. The Division Commander directed the Depot Quartermaster to take it over, and Captain Peter Murray, Quartermaster, 8th Infantry, was directed to report to him for that purpose. An office for this part of the transportation was established at Hamilton School, and in two days the number of hired teams for this part of the work was cut down from 557 to 109. The transportation scheme when perfected is summarized as follows:

The corral No. 1 at Presidio with 162 teams, government and hired, hauling from Entry No. 1 and Quartermaster Depot No. 1 to Subsistence Depots Nos. 1 and 3 and Quartermaster Clothing Stores No. 1 and 2.

The corral No. 2 at Folsom street dock with 45 teams and 21 four-line heavy trucks hauling from Entries No. 2, 3 and 4 to Subsistence Depots Nos. 2 and 3 and Quartermaster Clothing Depots Nos. 2 and 3. The 109 teams taken over from the city were used exclusively to haul from the various supply depots, Subsistence and Quartermaster, to the relief stations.

The population of San Francisco had spread over the surrounding country, refugees in large numbers going to San Jose, Oakland, Berkeley, Alameda and Sausalito and, naturally the people in these outlying towns demanded their proportionate share of relief. Officers were sent to the various interested sections and remained in charge, the system being similar to San Francisco. The distribution, however, of supplies over this enlarged territory added considerably to the burden which relief workers were already carrying.

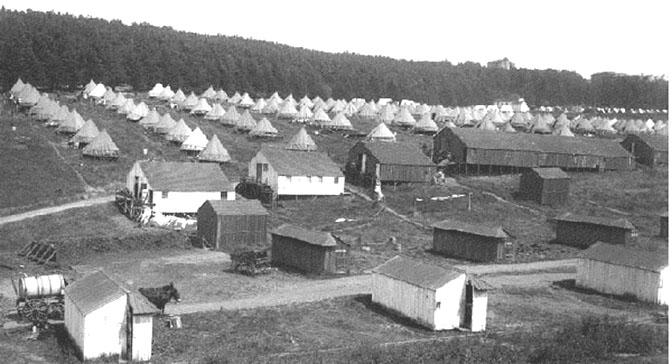

The system of camps adopted with attendant sanitation and rules for discipline and police is worth an independent article, and can only be briefly touched on in this lecture.

The gradual evolution of a completed camp system had kept pace from day to day with the growth of other relief work. As before stated, there were on hand at the Depot Quartermaster's storehouse for immediate issue some 3,000 tents (common), and 12,000 shelter tents. This canvas placed indiscriminately wherever ground was available initiated what grew into a very complete system of camps. By the prompt action of the War Department, tentage had been shipped by express from different depots in the United States and soon became available, there being finally issued some 25,000 tents, many of which were conical, and wall tents of large capacity. The tents when first obtained were placed on any vacant ground wherever space was immediately available, immediate shelter being the first requirement. Fortunately, San Francisco has many large and beautiful parks, among which Golden Gate park is one of the finest in the world. This available territory was looked over very carefully and a system of camps best adapted for supply, drainage, sewerage and sanitary arrangements was selected. A steam schooner loaded with a full cargo of lumber was found in the bay and taken possession of by the Depot Quartermaster and turned over to the Engineer Corps to begin a systematic construction of tent floors. Donated lumber poured in to such an extent afterwards that it was not necessary to make any further purchases. The transportation, however, of this lumber to the different outlying camps made quite a burden to the transportation facilities. As fast as camps were established the outlying and scattered tents in that vicinity were called in and placed systematically as a part of the camp. Each camp was known by number and each tent was known by number and such-and-such number of camp. An officer was placed in charge of each camp which, in fact, as far as administration was concerned, resembled a small military post. An army surgeon was also detailed to be in attendance and to be responsible for sanitation. It will be remembered that in these camps were all manner and class of people, some of whom knew absolutely nothing of the conditions of life under canvas. There were also many social differences and an occasional element of rowdyism and disregard of the rights of other people and the decencies of life that had to be suppressed. The administration required executive ability and discretion, and in nearly every instance the officers in charge proved themselves fully equal to the occasion.

Large

refugee camp in Golden Gate Park. The large wooden building along

the ridgetop was Affiliated Colleges,

now the site of the University of California Medical Center at

Parnassus Heights.

On May 29, General Orders were issued, defining the camps, the total at that time being twenty-one, eighteen of which were in San Francisco and the other three in outlying cities. Lieutenant-Colonel R. K. Evans, 5th Infantry, was placed in charge of all the camps by the Commanding General, with Captain M. J. Lenihan, 25th Infantry, as his Quartermaster, and other officers were detailed as assistants. Colonel Evans was afterwards relieved by Major Joseph A. Gaston, 1st Cavalry. The sanitary arrangements varied in regard to the different conditions. Eighteen camps were variously scattered through Golden Gate Park, the Presidio Military Reservation, what is known as Harbor View Flat, Fort Mason Military Reservation, and the various other parts of the city. The system usually adopted was that of the Reed trough and odorless excavator. A large number of the Reed troughs and odorless excavators had been shipped by express to San Francisco. There were no restrictions placed on the inmates of these camps save those required by decency, order and cleanliness. If the occupants persistently refused to obey the rules to meet the above requirements they were obliged to forego the benefits of government canvas and relief stores.

A Red Cross agent was stationed at each camp who attended to the registration of all the occupants in connection with their proper supply of food, clothing, etc.

The climatic conditions in California aided materially in the prevention of epidemics. Every day a strong fresh wind sets in from the Pacific Ocean and blows easterly across the city and, while it is not cold enough under usual conditions to create a serious chill, it purifies the atmosphere and prevents disease.

Water was furnished in abundance not only for drinking, but for washing, bathing, and laundry service. The potable condition of the water supply of each camp was determined weekly by means of cultures developed in the General Hospital.

There were some cases of typhoid fever and some cases of smallpox, but nothing even approaching an epidemic obtained.

The officers and men showed great adaptability and patience in the care and administration of these camps, and in this connection, this lecture would be incomplete without a brief reference to the heroes of "Jones dump." About dark, April 21, I was stopped near the Presidio bakery by a tall, earnest-looking young soldier of the 22d Infantry, who was walking down the road with two wagons. He inquired where he could get some bread, said the bakery was closed and he must have some food. I asked what he meant and who wanted the food. He then told me that he and two other members of his company had become separated from their command and found themselves near the foot of Jones street, just out of the burnt district in the vicinity of what is called "Jones dump," being a general dumping ground for that part of the city. He said they found about 5,000 dagoes down there who looked to them as wearers of the United States uniform to do something for them.

With true American spirit they accepted the responsibility and took charge. They levied on some adjoining stores and warerooms, making systematic issues. They settled disputes and maintained order. Finally, having exhausted all the resources of his immediate locality he had started out with two wagons on a foraging expedition, and he said "Those people are hungry and I have simply got to get something for them." I took him to the Presidio dock and loaded up his wagons, and asked Colonel Febiger that night if he would not visit the foot of Jones street the next morning and see what was going on. He reported that the man's story was all true. The three privates were running 5,000 refugees, mostly foreign, and doing it very well, and their authority down there was unquestioned. These refugees were taken in the general organized plan later and the enlisted men returned to their commands. This is only a minor incident in a great field of work, but it shows a trait in the American soldier, an ability to take the initiative and do his own thinking, which may enter largely into the history of some great war in the future. The work of the army in San Francisco from lack of time has only been outlined in this paper. To the careful observer it taught many lessons and was reassuring in in its results. One lesson is the necessity of eliminating liquor in any time of great stress. During the first day of the disaster, liquor could be obtained from deserted saloons, and on one street from rivers of wine running down the gutters from the bursted vats of the California Wine Association. Many cases of incidental trouble occurred. It would have been absolutely impossible to have kept adequate order among the great mass of refugees, some of whom were desperate and some of whom were lawless characters, if they could have obtained liquor. Oakland did not follow San Francisco's example and a guard had to be stationed at the ferry to keep drunken men from introducing liquor from the outside. We are taught that in any time of great emergency we must rely on the initiative of the men on the ground. Conditions were ever changing. Plans for one day or hour would not do for the next. The mental poise of the community had received a violent shock and whereas the greatest courage and patience was observed to generally obtain, the crank was there and the man who could see no suffering but his own. Dr. Devine asked an excited individual from an outlying district if there had been much of an earthquake out his way. "Earthquake," he replied, "Why that's where the earthquake was." There was a determined effort on the part of all leaders to work together, to bury individual preferences and opinions, to eliminate personality and work for the general good. It must not be taken for granted that all this harmony and unity of action came without effort. We have recently read of a disaster where such harmony did not prevail, and it is to the lasting credit of all men connected with the administration that they could not only work day and night and keep pace with ever shifting conditions but that they could work together. Hundreds of opportunities presented themselves as trouble makers. They were all promptly avoided. The Federal, State and Municipal Governments were all interested and represented. The army, navy, and National Guard were all actively at work. Nearly every society in America had interests at stake, yet through it all and from it all there was evolved a clean, thorough administration, absolutely free from graft or private gain, and in which the army played a leading part.

No single complaint was heard in the many long hours of heat, dust and turmoil by an officer or man that the work was too hard or the difficulties too great. All shoulders went willingly to the wheel, and with these six thousand soldiers thrown into most intimate daily association with 300,000 men, women and children, no incident is known of failure in duty or abuse of power.

The above article was taken from the Text Encoding Initiative Collections on sunsite.berkeley.edu (http://sunsite.berkeley.edu:2020/dynaweb)

Photos courtesy The Museum of the City of San Francisco, (sfmuseum.org)

SOLDIERS THREE AS GOOD AS A REGIMENT

Privates Demonstrate That it Doesn't Take Straps to Make Brains.

There isn't any Kipling to chronicle the adventures of these "Soldiers Three," but the irrepressible Mulvaney, Private Stanley Ortheris and Learoyd never had an adventure to compare with what befell their American prototypes, McGurty, Ziegler and Johnson of Company E, Twenty-second United States Infantry, during the San Francisco fire.

This trio of regulars, "recruited from God knows where," proved the ability of the American soldier to think and act for himself without any Congress-made officer to bawl drill regulations. It also disproved the the allegation recently made by a Cabinet officer that "service in the army disqualifies men for using their brains in emergencies."

This is what happened to the three: Separated from their command while trying to save fire apparatus.

WHAT THEY DID

This is what they did: Organized a relief expedition of their own. Formed wagon trains by pressing vehicles into service with no other badge of authority than a rifle made by Jorgensen and Krag, and transported supplies for refugees at North Beach. Built two villages, one for 1,500 people and another of tents for 500 people.

McGurty took charge of operations—his name tells why—and with his mates showed the people how to put up army tents. Like Tom Sawyer and his white-washing, those three soldiers made the refugees think that putting up tents was fun, and the white city went up as easily as an army corps going into camp.

"We didn't have no authority," says McGurty, "but something had to be done, and it seemed to be up to us. Of course, we wouldn't have shoot anybody, but we had our Krags and 120 rounds of ammunition each, and our [two words missing].

"One Italian I tried to make work complained that he was sick and had nothing to eat. I went to his shack and found that he had a pile of stuff which he had looted. He went to work.

"Sometimes we handled our rifles and bayonets just to make our bluff hold water, but there were many good men working with us who backed us up in everything we did and kept the crowd going our way.

About the 22nd Colonel [Lea] Febiger found us while he was on a tour of inspection. We showed him what we were doing, and he told us to go ahead.

"He got us an order from the Mayor assigning me in charge of a food supply station at Bay and Montgomery streets [now Bay and Columbus Ave. near Fishermen's Wharf] and giving me a pass to and from the Folsom-street supply station.

"We held the job down ten days, and besides feeding the people of the neighborhood, we issued 2,000 pairs of blankets, 1,500 pairs of men's shoes, 2,500 pairs of women's and children's shoes.

"In one place we found a bunch of Chinamen in the top of a cannery with a lot of choice provisions.

"I picked out a big chink and asked him if he wanted to work. 'No,' he said; 'me slick.' I made a pass with my gun and cured him.

"There was piled in the neighborhood at this time 4,000 cases of champagne and about fifty barrels of red wine. How did I know it was red? Just smelled it. These were claimed by private persons, but we would not allow them to break them open or carry any away.

THOUGHT THEY HAD DESERTED

"All this time we were absent from the company and our Captain thought we had deserted, but Colonel Febiger fixed it up for us. We were finally relieved by a Red Cross man, and we hunted up our company, and reported for duty."

Colonel Febiger applied to Major-General Greely for these men and they were detailed on special duty around his headquarters.

Privates Frank P. McGurty, William Ziegler and Henry Johnson have all heard the bullets singing about their ears, and they know the bolo-rush of the fanatical Moro. The Twenty-second Infantry saw hard service with the third Sulu expedition of General Wood, during which several engagements were fought in a march of 150 miles, twenty-eight datos or native chiefs captured and 141 rifles.

In the campaign of the allied forces before Pekin foreign critics commented freely upon the apparent lack of discipline and the "devil-may-care" of the American soldiers.

The military power of the United States lies in the fact that the American regular soldier can be a machine when a machine is needed, but when a command is so separated that each man acts on his own iniitiative Mr. Private Soldier uses his brains as well as his eyes, whether his name be McGurty, Ziegler or Johnson, or any other American sounding name.

San Francisco Examiner

June 10, 1906

HEADQUARTERS PACIFIC DIVISION

SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA

August 20, 1906

To the

Military Secretary Pacific Division.

San Francisco, California.

Sir-

In reply to the 7th Endorsement on my letter of June 22nd, 1906, to the Regimental Commander, 22nd Infantry, calling his attention to certain men of his regiment, whose actions I considered entitled them to special recognition; I have the honor to state as follows, in reply from the office of the Chief of Staff of the Army.

When inspecting on the morning of April 23rd, I found McGurty and Johnson in charge of this colony, issuing and guarding supplies. In reply to my inquiry of McGurty as to how they guarded their supplies at night, he said he and Johnson mounted post alternately every few hours, relieving each other as they could not trust the refugees. I then suggested that they secure another man to help them, as the work would wear them out. The next morning, the 24th, I found that Ziegler had joined them, and from then on he was associated with them. The addition of his services were much needed, but I was not told then, nor do I know now, how McGurty secured them.

Privates McGurty and Johnson alone established this station and colony, and were the ones who took the original initiative, and organised everything that I found, and though Pvt. Zieglers work was most necessary and of the greatest assistance, he is not entitled to as much credit as the other two, who showed such administrative ability and sound judgement, when everything was in a chaotic state.

Very Respectfully,

(signed) Lea Febiger

Lieut. Colonel 3d. Infantry.

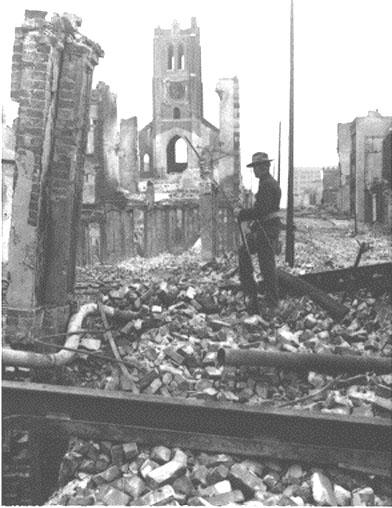

Lone soldier stands guard along Dupont Street (now Grant Avenue) near St. Mary's Church.

The above articles and photos courtesy The Museum of the City of San Francisco, sfmuseum.org

Our heartfelt thanks to Gladys Hansen and the Museum of the City of San Francisco,for allowing us to use their articles, photos and letters.

The Museum's hard work in researching and presenting the history of San Francisco can be viewed on their excellent website by clicking on the following logo:

Home | Photos | Battles & History | Current |

Rosters & Reports | Medal of Honor | Killed

in Action |

Personnel Locator | Commanders | Station

List | Campaigns |

Honors | Insignia & Memorabilia | 4-42

Artillery | Taps |

What's New | Editorial | Links |