San Francisco Earthquake

1906

Part One

|

As fires rage through San Francisco, soldiers,

dressed in olive drab service dress with strapped

leggings and wearing campaign hats with light blue cords

designating infantry, unload one of many civilian wagons

pressed into service with their drivers. (In addition to

supplies from Army depots, food, including much flour,

came from cities all over the United States.) The officer with the black visored

service cap is a lieutenant colonel of infantry. With his

olive drab, single breasted sack coat, with four

chokedbellow pockets, low falling collar and dull finish

bronze metal buttons he wears olive drab service breeches

and russet leather boots. The officer and the artillery

sergeant known by his scarlet hat cord carry .38 caliber

service revolvers; the rifles shown are the new .30

caliber 1901 "Springfields."

by H Charles McBarron

Illustration: US Army Center of

Military History

|

The 22nd Infantry was one of the

units sent to aid the City of San Francisco during this great

tragedy.

How the Army Worked to Save San Francisco

Personal Narrative of the Acute and Active

Commanding Officer of the Troops at the Presidio

BY FREDERICK FUNSTON

BRIG.-GEN. U. S. A.

How lucky it was for San Francisco that Gen. Frederick

Funston threw himself and his men so boldly into the breach when

the fire-fighters were waging their unequal combat with the

flames caused by the great earthquake of April 18th, has been

remarked on every hand. The newspapers and weekly periodicals

have covered the ground of the great catastrophe so far as

general description goes, but the Cosmopolitan has been

singularly fortunate in securing from General Funston the

following and spirited account of how he summoned his men from

the Presidio, how they dashed down to the scene of the

conflagration to help the firemen, to patrol the city, to save

lives, to care for the wounded and to feed the hungry. and of

their subsequent deeds.

Modesty is written on every page of this report. General

Funston gives a fine account of what he saw at the beginning of

the catastrophe: he tells how the policing-squads were organized,

and gives much valuable information not before set forth. But as

to how heroically he and his men worked in the vain fight to save

the city with dynamite, he is silent, and of the numberless

instances of lives saved and hungry mouths fed he makes little

account. In this respect he is like Kipling’s heroic soldier

— “he has done the fighting, but he can’t tell

about it.”

Still the narrative stands as a unique contribution to

the history of the great disaster, and is vitally interesting

throughout. — Editor’s Note.

WHEN first approached by a

representative of the Cosmopolitan with the request that I

prepare a short sketch of the work of the army in maintaining

order and in sheltering and feeding the homeless during the first

few days of the San Francisco fire, I declined, because of the

seeming impropriety of such action, but reconsidered on its being

pointed out to me that the public interest in the action of the

military authorities in connection with the recent catastrophe

was so keen that an authoritative statement from one in a

position to be cognizant of all the facts would be most welcome.

Few people ever see official reports; but hundreds of thousands

read so widely circulated a magazine as the Cosmopolitan. This

communication, in connection with the fact that the necessary

permission has been obtained from the secretary of war, must be

my apology.

At the time of the

earthquake there were stationed at the military posts on or near

San Francisco Bay ten companies of Coast Artillery; the First,

Ninth, and Twenty-fourth Batteries of Field Artillery; the

entire Twenty-second Regiment of Infantry; Troops I,

K, and M, Fourteenth Cavalry; Company B, Hospital Corps— an

aggregate of about seventeen hundred men. Of these, two companies

of the Twenty-second Infantry and the troops of the Fourteenth

Cavalry were temporarily absent on the rifle-range at Point

Bonita; but they were soon available for duty, the cavalry being

brought to San Francisco.

The headquarters of the

Pacific Division and of the Department of California were located

in office-buildings in the heart of the city, and the officers on

duty thereat lived in the city and not at the army posts near it.

Maj.-Gen. A. W. Greely, commanding the Pacific Division, had

departed from the city on a visit to his home in Washington only

a few days previous to the earthquake, which accounts for the

writer, as senior officer, being in command until the return of

the division commander.

I was living with my

family at 1310 Washington Street, near Jones, one of the most

elevated parts of the city, and was awakened by the earthquake

shock at 5:16 a.m. on that never-to-be-forgotten eighteenth day

of April. The entire street-car system being brought to a

standstill by the damage resulting from the shock, I hastened on

foot toward the business section of the city for the purpose of

ascertaining what damage had been done to the hotels and other

large buildings. Arriving at the highest part of California

Street, on what is popularly known as “Nob Hill,”

several columns of smoke were seen rising from the region south

of Market Street, with others rising apparently from fires in the

banking district. Walking rapidly down California to Sansome, I

found that several fires were burning fiercely, and that the city

fire-department was helpless, owing to water-mains having been

shattered by the earthquake.

I realized then that a

great conflagration was inevitable, and that the city police

force would not be able to maintain the fire-lines and protect

public and private property over the great area affected. It was

at once determined to order out all available troops not only for

the purpose of guarding federal buildings, but to aid the police-

and fire-departments of the city.

Now it was ascertained

that the entire telephone system was prostrated and that I must

return to first principles in order to get into communication

with the commanding officers at the Presidio and Fort Mason, the

two army posts most convenient to the city. Several men dashing

wildly about in automobiles declined to assist me, for which I

indulged in the pious hope that they’d be burned out. So I

made my way, running and walking alternately, from Sansome Street

to the army stable on Pine, near Hyde, a little more than a mile,

where I arrived in so serious a condition that I could scarcely

stand. Directing my carriage driver to mount my saddle-horse, I

hastily scribbled a note to Col. Charles Morris, Artillery Corps,

commanding officer at the Presidio, directing him. to report with

his entire command to the chief of police at the Hall of Justice

on Portsmouth Square, and sent a verbal message of the same

import to Capt. M. L. Walker, Corps of Engineers, in command at

Fort Mason. The messenger was well mounted and covered the mile

to Fort Mason and the three miles to the Presidio at a keen run.

Both Colonel Morris and Captain Walker had their commands well in

hand and responded with alacrity.

Before leaving Sansome

Street I had asked a member of the city police force to inform

the chief of police as soon as possible as to the action I

contemplated taking.

Leaving the stable, I

walked in a leisurely manner to the summit of Nob Hill, only a

few blocks distant, whence could be obtained a good view to the

south and cast across the great city doomed to destruction. The

streets were filled with people with anxious faces, all turned

toward the dozen or more columns of thick black smoke rising from

the densely populated region south of Market Street. The thing

that at this time made the greatest impression on me was the

strange and unearthly silence. There was no talking, no apparent

excitement among the near-by spectators; while from the great

city lying at our feet there came not a single sound, no

shrieking of whistles, no clanging of bells. The terrific roar of

the conflagration, the crash of falling walls, and the dynamite

explosions that were to make the next three days hideous, had not

yet begun.

It was a beautiful clear

morning with no wind, and the sinister column of smoke mounted a

thousand feet in the air before they were dissipated. Probably

none of the people who watched the imposing spectacle on that

occasion would have believed that within thirty-six hours the

spot where they stood would be a maelstrom of fire. Walking now

to my home, only four blocks distant, I had a cup of coffee and

gave a few hasty instructions to my family about packing trunks

and leaving the house, so soon to be destroyed. From here it was

a walk of fifteen minutes to the Phelan Building, the

headquarters of the Department of California, where I found

awaiting me several officers of the Pacific Division and the

Department of California.

Market Street was full of

excited, anxious people watching the progress of the various

fires now being merged into one great conflagration. A few

moments before seven o’clock there arrived the first

detachment of regular troops, the men of the Engineer Corps at

Fort Mason. They were greeted with evidentwill by the crowd, and

made a fine impression with their full cartridge-belts and fixed

bayonets. They had marched from Fort Mason to the Hall of

Justice, where they had been reported to the chief of police, and

were now being distributed along Market Street, two to each

block, with instructions to shoot instantly any person caught

looting or committing any serious misdemeanor.

Their presence had an

instantly reassuring effect on all awe-inspired persons.

It was considered most

desirable to bring to the city at once the battalion of

the Twenty-second Infantry stationed at Fort McDowell,

on Angel Island, in San Francisco Bay. All telegraphic

communication being cut off, the large army-tug Slocum

was dispatched to that fort with verbal orders to Col.

Alfred Reynolds to embark his command at once, land at

the foot of Market Street and march to the Phelan Building.

In the meantime, the

clerks and messengers who had reported for duty set about saving

the records of the department in the offices on the fourth floor.

As fast as the records could be brought out they were placed in a

wagon for transportation to Fort Mason. About eight o’clock

a.m. there came so severe an earthquake shock that I directed

that all attempts to save records and papers cease, not deeming

them of sufficient importance to risk the lives of a dozen men,

Before this time, however, troops from the Presidio began to

arrive— cavalry, coast artillery armed and equipped as

infantry, and field artillerymen mounted on their battery horses.

Abundant use was found for

all the troops at our disposal, for the conflagration with a mile

of front was rapidly eating its way into the heart of the city,

and the streets were black with tens of thousands of people who

were kept at a distance of two blocks from the fire by strong

detachments of troops. Before ten o’clock the troops from

Forts McDowell and Miley had arrived and there were now on duty

about seventeen hundred regulars. They were used in various ways,

guarding the people, the Sub-Treasury and the Mint, patrolling

the streets to prevent looting, maintaining fire-lines, and

taking a hand at the hose wherever there was sufficient water

pressure to enable the firemen to accomplish anything.

While not acting under the

orders of the officers of the police- and fire-departments, the

officers of the troops consulted them and complied with their

wishes in every possible way.

There was absolutely no

friction.

In the meantime, dynamite

had been obtained; and then began the series of terrific

explosions that was to shake the city for the next few days. The

amount of dynamite available in the earlier hours of the day was

too small to accomplish much, but a tug was obtained and a number

of trips made to the works of the California Powder Company at

Pinole, the tug returning each time laden with explosives. I

doubt if anyone will ever know the amount of dynamite and

guncotton used in blowing up buildings, but it must have been

tremendous, as there were times when the explosions were so

continuous as to resemble a bombardment.

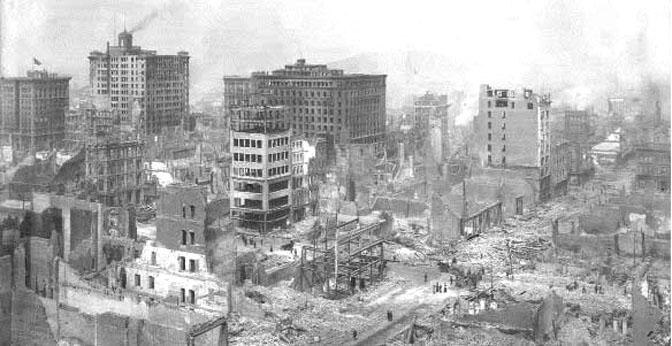

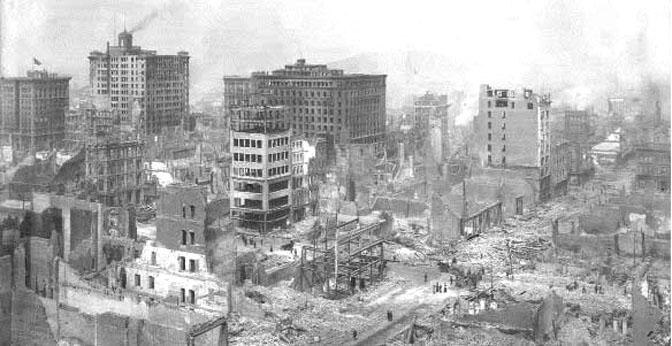

Panorama

of the Destroyed City.

Three

surviving structures in the Financial District can be seen in

this dramatic photo. At far left is the Kohl Building on

Montgomery Street, the Merchants' Exchange Building on California

and, in the center of the picture, the Mills Building on

Montgomery.

Most of the work was done

under the instructions of Captain Coleman

and Lieutenant Briggs, Artillery Corps, U. S. A., who, however,

ascertained the wishes of the fire- and police-officials as to

the buildings to be destroyed. In this work Lieutenant Pulis of

the Artillery Corps was very seriously injured by a premature

explosion. While frame and old brick buildings were reduced to

piles of rubbish by these explosions, the modern steel and

concrete structures remained as impervious to the heaviest

charges as they had been to the earthquake.

I had several times during

the day been in consultation with Mayor Schmitz and Chief of

Police Dinan at the Hall of Justice, which was the headquarters

of the city officials until forced out by the approach of the

conflagration. At the last one of these conferences it was

arranged that during the night the regular troops should patrol

the wealthy residence district west of Van Ness Avenue, in order

to prevent robbery or disorder by the vast throngs being driven

thither by the progress of the fire. For this duty I placed all

troops in the city under the command of Col. Charles Morris,

Artillery Corps, who established his headquarters in the district

to be patrolled.

It is useless to attempt

to go into a detailed account of the events of that night of

horrors. Four square miles of the city were on fire. The night

was as light as day, and the roar of the conflagration, the crash

of falling walls, and the continuous explosions made a

pandemonium simply indescribable. During the night, the Grant

Building, headquarters of the Pacific Division, and the Phelan

Building, for so many years headquarters of the Department of

California, had gone up in the general holocaust; and the

officers on duty in the city assembled and reëstablished

headquarters at Fort Mason, the small and ancient army post on

the bay shore, at the north end of Van Ness Avenue.

An account of the events

of the succeeding two days would unduly lengthen what is meant to

be a brief sketch. Block by block and street by street and hour

after hour the firemen, police, and soldiers fought the

conflagration, in hope of possible success. Scores of buildings

were blown down by dynamite and guncotton, and others were set on

fire in order to check the conflagration by back-firing. The

Pacific Squadron, under command of Admiral Goodrich, arrived from

the south and landed several hundred marines and blue-jackets,

who rendered excellent service in fighting the fire and

patrolling the streets.

During the memorable 18th

and 19th every hotel and bank, every large store and nearly every

storeroom and wareroom in the city had been destroyed, three

hundred thousand people were homeless, and thousands more were

left without the means of livelihood.

The rations, tents, and

blankets on hand at the army posts adjacent to the city were

dealt out to the sufferers with no account of the responsibility

involved; and within two days, relief supplies from neighboring

states and cities and army supplies from various army posts had

begun to arrive and were being distributed under the supervision

of Maj. C. A. Devol, depot quartermaster, and Maj. C. R.

Krauthoff, depot commissary.

The sick from the city

hospitals and many of those injured in the earthquake were sent

to the general hospital at the Presidio.

The Hearst Relief Corps

with a number of well-equipped hospitals, and a complement of

physicians and nurses, arrived from Los Angeles and rendered

excellent service.

In a few days conditions

were as normal as could be expected under the circumstances, and

the work of feeding and sheltering the homeless thousands

proceeded in a systematic manner.

Through all this terrible

disaster, the conduct of the people had been admirable. There was

very little panic and no serious disorder. San Francisco had its

class of people, no doubt, who would have taken advantage of any

opportunity to plunder the banks and rich jewelry and other

stores of the city, but the presence of the square-jawed silent

men with magazine rifles, fixed bayonets, and with belts full of

cartridges restrained them. There was no necessity for the

regular troops to shoot anybody and there is no

well-authenticated case of a single person having been killed by

regular troops.

Two men were shot by the

state troops under circumstances with which I am not familiar,

and so I am not able to express an opinion, and one prominent

citizen was ruthlessly slain by self-constituted vigilantes.

If there is any lesson to

be derived from the work of the regular troops in San Francisco,

it is that nothing can take the place of training and discipline,

and that self-control and patience are as important as courage.

Preferred citation:

Funston, Frederick. “How the Army Worked to Save San

Francisco.” Cosmpolitian MagazineJuly

1906. http://www.sfmuseum.org/1906/cosmo.html (5 Mar. 1996)

The above

is courtesy of The Museum of the City of San Francisco

(sfmuseum.org)

The Army in the San Francisco

Disaster.

BY Major Carroll Augustine Devol, 1859

Quartermaster, G. S., U. S. Army.

It is presumed that all Army men are more or

less familiar with the city of San Francisco. To give a rough

idea of its size it will be noted that the distance from the

Ferry Building to the Cliff House is about seven miles, and from

Fort Mason to the southern city limits is about six miles. The

burnt district is four miles from north to south, by two and a

half from east to west.

On April 18, 1906, San Francisco may be

considered to have had a population of 400,000 people. To subsist

this number on the army ration would require about 1,600,000 lbs.

of food daily. This means 800 tons or about forty car loads. This

for food only. The supply of any great city is the result of many

years of gradual evolution of trade conditions created by

business experience, requirements, and conditions, changing to

keep pace with the city's growth. The other conditions relating

to the general welfare of humanity, such as municipal laws,

health regulations, habitable dwellings, adequate water supply,

proper sewer systems, are all the result of gradual and

painstaking development and built upon many years of experience.

The system is so gradual and so perfect that the results are

taken as a matter of course, and the daily supply of everything

that money will purchase is regarded to be as much of a certainty

as that daylight will succeed the night.

This certainty existed in the minds of the

people of San Francisco at 5 A.M., April 18. Fifteen minutes

later the entire system was reduced to chaos. Daylight arrived

but with it nothing but ruin. The population was in a few moments

carried back to absolutely primitive conditions, no food, no

shelter, and with the purchasing power of money eliminated. The

millionaire was but little better off than the pauper. On the

little Presidio dock, crowded with refugees, at the same time

were seen Caruso, the multimillionaire Spreckels, other men of

note and wealth, together with people without a dollar in the

world, elbow to elbow, all facing the same condition and one no

better off than the other. The army received but little injury in

the great catastrophe. The army represented law and order, and it

was to the army the people looked for leadership and assistance.

General Funston at once ordered into the city all available

troops. No martial law was proclaimed and none necessary. The

troops were ordered to report to and assist the Chief of Police.

At 7:45 A.M., Companies C and D, Engineer

Corps, arrived from Fort Mason and were reported to the Mayor and

Chief of Police. They were directed by the former to guard the

banking district and send patrols along Market street to prevent

looting. At 8:00 A. M., the Presidio garrison, consisting of the

10th, 29th, 38th, '66th, 67th, 70th and 105th Companies of Coast

Artillery; Troops I and K, 14th Cavalry; and the 1st, 9th and

24th Batteries of Field Artillery began to arrive. Details were

sent to guard the mint and post-office, while the remainder

assisted the police in keeping the dense crowds away from the

dangerous buildings and patroling the streets to keep order and

prevent looting. Most fortunately for San Francisco they had a

live mayor, a man ready, tactful and resourceful. He at once

ordered all saloons closed and kept them closed. The benefits of

this order were far-reaching and assisted the army very greatly

in keeping order.

The Headquarters and 1st Battalion 22d

Infantry, were brought from Fort McDowell by boat, arriving

at 10:00 A.M., and were held for a time in reserve at O'Farrell

street. They were later utilized as patrols and as an assistance

to the fire department. The Fort Miley troops, the 25th and 64th

Companies Coast Artillery, had a longer march and did not arrive

until 11:30 A.M.

Troops subsequently arrived in the city as

follows: On April 19, Companies E and G, 22d Infantry,

from Alcatraz Island; Companies K and M, 22d Infantry,

from the depot of recruits and casuals, and the 32d, 61st and

68th Companies Coast Artillery, from Fort Baker;

April 21. Headquarters and two battalions 20th

Infantry, from Presidio of Monterey;

April 22. Headquarters and ten companies 14th

Infantry, from Vancouver Barracks;

April 23. The 17th and 18th Batteries Field

Artillery from Vancouver Barracks.

These troops were all stationed in the Pacific

Division and were ordered to San Francisco by the Division

Commander. Troops arriving later by orders from the War

Department will be enumerated later. It is believed the prompt

appearance of the United States troops on the streets of the city

was an object lesson to the minds of the evil-disposed, reminding

them that the law of the land still existed with ready and

powerful means at hand to enforce it, and was of incalculable

moral and material benefit to the city.

On April 18 the Headquarters of the Pacific

Division was located in what was known as the Grant Building on

Market street, and Department Headquarters in the Phelan

Building, O'Farrell and Market streets. Both buildings were

destroyed by fire. General Funston moved into the Commanding

General's quarters at Fort Mason, establishing both Division and

Department Headquarters at that point, and the Signal Corps

immediately began to stretch wires for telegraph communication to

various points of importance in the city.

On the evening of the 18th, by agreement with

the Mayor and Chief of Police, the city was divided into sections

and all that part west of Van Ness avenue was assigned to the

regular troops. The government forces, however, still assisted in

fighting fire and particularly in the use of dynamite in advance

of the fire line. All available explosives had been sent in from

the Presidio on the 18th, consisting of 48 barrels of powder and

300 pounds of dynamite. Shortly afterwards a large amount of

dynamite was procured from the California Powder Works. The water

mains were broken in hundreds of places and there was no water to

fight fire. The dynamite was very efficiently handled by the

troops and the fire department, but its utility in a great fire

unassisted by water has always been questioned. Many varying

opinions were formed and expressed by people in a position to

know, but the results were not conclusive. Personally I think it

did no good, perhaps harm.

The fire had started in many places south of

Market Street, and by noon on April 18 the Commissary Depot and

the Quartermaster Depot with some 2,000,000 dollars worth of

quartermaster stores was destroyed. The fire spread east and west

and jumped Market street in several places. Class A buildings,

heretofore known as fireproof, with steel shutters and metal

window casings, built of steel, protected with reinforced

concrete, absolutely modern and up-to-date, burned as fiercely as

the older buildings. An example is shown in the St. Francis

Hotel, which is damaged fully 50 per cent of its original cost,

from which it may be safely concluded that although the shell of

a building is non-combustible its utility requires that it be

filled with furniture and combustible material, with the result

that there is no such thing as a fireproof building. The fire

extended in a mighty furnace over a frontage of three miles as

shown. This is probably the best picture of the greatest fire

ever known. On the afternoon of the 20th the fire had practically

subsided. The final stand was made on Van Ness avenue about five

blocks south from Fort Mason. Water was then pumped from the bay,

and although the houses across this wide street caught fire

several times, determined effort prevented its spreading west

from this point. The fire also jumped south of this point the day

previous, but was held as indicated. On the 21st a high wind from

the west carried the fire from Russian Hill down towards the

water front, still undamaged. It consumed the large lumber yards

south of the barge office and swept eastward. Had the fire ever

gotten into the line of docks the water communication of San

Francisco would have been doomed. All the tugs in the harbor,

including two fire patrol boats, one navy yard tug, the Army

Transport Tug Slocum and Army Tug McDowell, probably twenty all

told, combined near the foot of Lombard street, stretching hose

up to meet the fire and pumping salt water with all available

power. The wind blew a hurricane, but the tugs stuck to their

work heroically, the tug Slocum being obliged to play a hose on

her own deck-house to keep it from catching fire from the intense

heat and falling cinders. By morning of the 23d, five days after

the outbreak, the fire was under control and the great San

Francisco conflagration had passed into history.

The system of camps adopted with attendant

sanitation and rules for discipline and police is worth an

independent article, and can only be briefly touched on in this

lecture.

The gradual evolution of a completed camp

system had kept pace from day to day with the growth of other

relief work. As before stated, there were on hand at the Depot

Quartermaster's storehouse for immediate issue some 3,000 tents

(common), and 12,000 shelter tents. This canvas placed

indiscriminately wherever ground was available initiated what

grew into a very complete system of camps. By the prompt action

of the War Department, tentage had been shipped by express from

different depots in the United States and soon became available,

there being finally issued some 25,000 tents, many of which were

conical, and wall tents of large capacity. The tents when first

obtained were placed on any vacant ground wherever space was

immediately available, immediate shelter being the first

requirement. Fortunately, San Francisco has many large and

beautiful parks, among which Golden Gate park is one of the

finest in the world. This available territory was looked over

very carefully and a system of camps best adapted for supply,

drainage, sewerage and sanitary arrangements was selected. A

steam schooner loaded with a full cargo of lumber was found in

the bay and taken possession of by the Depot Quartermaster and

turned over to the Engineer Corps to begin a systematic

construction of tent floors. Donated lumber poured in to such an

extent afterwards that it was not necessary to make any further

purchases. The transportation, however, of this lumber to the

different outlying camps made quite a burden to the

transportation facilities. As fast as camps were established the

outlying and scattered tents in that vicinity were called in and

placed systematically as a part of the camp. Each camp was known

by number and each tent was known by number and such-and-such

number of camp. An officer was placed in charge of each camp

which, in fact, as far as administration was concerned, resembled

a small military post. An army surgeon was also detailed to be in

attendance and to be responsible for sanitation. It will be

remembered that in these camps were all manner and class of

people, some of whom knew absolutely nothing of the conditions of

life under canvas. There were also many social differences and an

occasional element of rowdyism and disregard of the rights of

other people and the decencies of life that had to be suppressed.

The administration required executive ability and discretion, and

in nearly every instance the officers in charge proved themselves

fully equal to the occasion.

On May 29, General Orders were issued, defining

the camps, the total at that time being twenty-one, eighteen of

which were in San Francisco and the other three in outlying

cities. Lieutenant-Colonel R. K. Evans, 5th Infantry, was placed

in charge of all the camps by the Commanding General, with

Captain M. J. Lenihan, 25th Infantry, as his Quartermaster, and

other officers were detailed as assistants. Colonel Evans was

afterwards relieved by Major Joseph A. Gaston, 1st Cavalry. The

sanitary arrangements varied in regard to the different

conditions. Eighteen camps were variously scattered through

Golden Gate Park, the Presidio Military Reservation, what is

known as Harbor View Flat, Fort Mason Military Reservation, and

the various other parts of the city. The system usually adopted

was that of the Reed trough and odorless excavator. A large

number of the Reed troughs and odorless excavators had been

shipped by express to San Francisco. There were no restrictions

placed on the inmates of these camps save those required by

decency, order and cleanliness. If the occupants persistently

refused to obey the rules to meet the above requirements they

were obliged to forego the benefits of government canvas and

relief stores.

A Red Cross agent was stationed at each camp

who attended to the registration of all the occupants in

connection with their proper supply of food, clothing, etc.

The climatic conditions in California aided

materially in the prevention of epidemics. Every day a strong

fresh wind sets in from the Pacific Ocean and blows easterly

across the city and, while it is not cold enough under usual

conditions to create a serious chill, it purifies the atmosphere

and prevents disease.

Water was furnished in abundance not only for

drinking, but for washing, bathing, and laundry service. The

potable condition of the water supply of each camp was determined

weekly by means of cultures developed in the General Hospital.

There were some cases of typhoid fever and some

cases of smallpox, but nothing even approaching an epidemic

obtained.

The officers and men showed great adaptability

and patience in the care and administration of these camps, and

in this connection, this lecture would be incomplete without a

brief reference to the heroes of "Jones dump." About

dark, April 21, I was stopped near the Presidio bakery by a tall,

earnest-looking young soldier of the 22d Infantry, who was

walking down the road with two wagons. He inquired where he could

get some bread, said the bakery was closed and he must have some

food. I asked what he meant and who wanted the food. He then told

me that he and two other members of his company had become

separated from their command and found themselves near the foot

of Jones street, just out of the burnt district in the vicinity

of what is called "Jones dump," being a general dumping

ground for that part of the city. He said they found about 5,000

dagoes down there who looked to them as wearers of the United

States uniform to do something for them.

With true American spirit they accepted the

responsibility and took charge. They levied on some adjoining

stores and warerooms, making systematic issues. They settled

disputes and maintained order. Finally, having exhausted all the

resources of his immediate locality he had started out with two

wagons on a foraging expedition, and he said "Those people

are hungry and I have simply got to get something for them."

I took him to the Presidio dock and loaded up his wagons, and

asked Colonel Febiger that night if he would not visit the foot

of Jones street the next morning and see what was going on. He

reported that the man's story was all true. The three privates

were running 5,000 refugees, mostly foreign, and doing it very

well, and their authority down there was unquestioned. These

refugees were taken in the general organized plan later and the

enlisted men returned to their commands. This is only a minor

incident in a great field of work, but it shows a trait in the

American soldier, an ability to take the initiative and do his

own thinking, which may enter largely into the history of some

great war in the future.

Our heartfelt thanks to Gladys

Hansen and the Museum of the City of San Francisco,for allowing

us to use their articles, photos and letters.

The Museum's hard work in

researching and presenting the history of San Francisco can be

viewed on their excellent website by clicking on the following

logo:

BACK

Home | Photos | Battles & History | Current |

Rosters & Reports | Medal of Honor | Killed

in Action |

Personnel Locator | Commanders | Station

List | Campaigns |

Honors | Insignia & Memorabilia | 4-42

Artillery | Taps |

What's New | Editorial | Links |