![]() 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry

1st Battalion 22nd Infantry ![]()

The 22nd U.S. Infantry Regiment in the Spanish-American War

by Bob Babcock

Part Two

An extract from "Combat Diary - Episodes from the history of the Twenty-Second Regiment, 1866-1905" by A. B. "Bud" Feuer (used with permission of the author) and from "A History of the Twenty-Second United States Infantry" from official records compiled by Captain W. H. Wassell, 22nd Infantry and published in the Philippines in 1904 (from the 22nd Infantry Regiment Society archives).

This compilation and extract from the two books was done in 1998 in honor of the 100th anniversary of the Spanish-American War and expanded and updated on April 6, 2002 in honor of "Task Force Regulars" movement to Cuba. Written by Bob Babcock, veteran of B/1-22 1965-1967 and president of the 22nd Infantry Regiment Society. Deeds not Words!

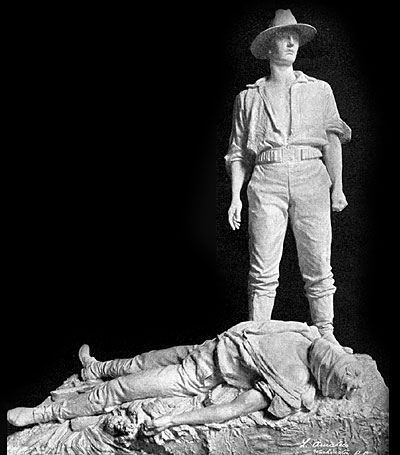

A U.S. Infantryman stands by the body of a fallen comrade

in a sculpture by Louis Amateis, entitled "El Caney"

Battle of July 1 and July 2, 1898:

On July 1, 1898, General Ludlow's First Brigade slowly approached El Caney. Captain Wassell described the action: "The 22nd Infantry led the advance along a trail overgrown with brush and vines until we reached the main Santiago-El Caney road near the Ducoureaud House. The Second Battalion was then deployed and skirmished northward through the jungle to check if there were any paths over which the Spaniards in the town might escape to Santiago. The First Battalion continued along the main road toward El Caney. About a thousand yards from the city, Company A, our advance guard, came under sharp Mauser fire. The battalion deployed rapidly east and west of the road. LTC Patterson was severely wounded by the sudden enemy attack, and Major Van Horne took over command of the Regiment.....For more than a half-hour we cut through undergrowth and tangled vegetation, which was so dense that the battalion could not see more than ten feet to the front. In order to keep the line in order, men were continually forced to call out their position to skirmishers on either side of them..." After three hours of battle, the First Battalion had crept to within seven hundred yards of the enemy positions - suffering heavy losses in the process.

Meanwhile at El Caney, the Second Battalion of the 22nd Infantry, under the command of Captain B. C. Lockwood, was located to the extreme left of General Ludlow's line. The battalion received orders to hack its way through the jungle for half a mile, then swing east until they came to the Cuabietas road. This was to be their assigned position to block any enemy retreat from the town.

As Lockwood's troops cut their way through the heavy underbrush, they came under fire from Spanish snipers. The advance was so difficult that it was impossible to keep the formation together. Captain Robert Getty's company became separated from the rest of the battalion. They reconnoitered the area west of Lockwood's position, and succeeded in cutting the El Caney telephone line along the Cuabietas road. Getty rejoined the battalion at the edge of the fire-swept clearing, about five hundred yards from the trenches and main blockhouse.

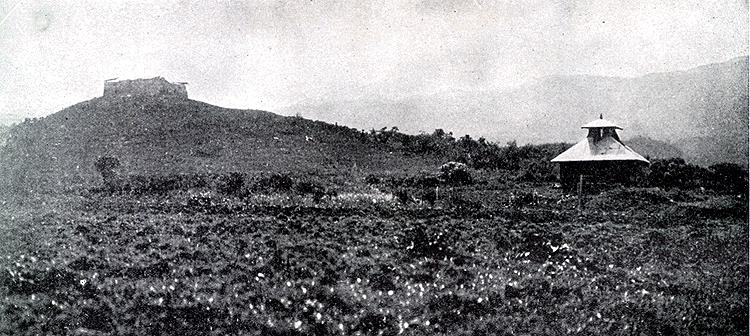

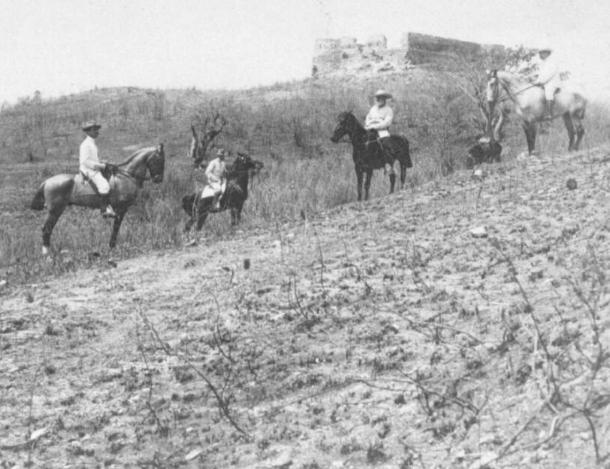

On the hill in the background is the fort of El Viso,

the main defensive position of the Spanish forces at El Caney

Captain Wassell narrated: "The Spanish use of barbed wire proved to be very effective in stopping our advance. Wires were stretched near the ground to trip our men when they would run from one location to another. A few yards beyond, the Spaniards had constructed tall fences -strung with many lines of wire. These defenses were laid in cultivated valleys and other open spaces near the entrenchment's. Enemy snipers were posted in the treetops around the clearings. Every fence compelled a momentary halt in our progress - and during those moments, we were exposed to pitiless fire. From noon until one o'clock there was a lull in the fighting, and men with wire cutters moved forward. Taking advantage of bushes and dips in the ground, they crawled to within two hundred yards of the trenches and cut many of the wires. They returned to our lines safely. Owing to the great extent of the front occupied by the Regiment, General Ludlow moved the Second Battalion still farther to the west, and advanced the First Battalion to within five hundred yards of the enemy. The 8th Infantry was positioned between the First and Second Battalions."

About one o'clock, the Spaniards increased their firing with renewed vigor. The Americans were forced to hug the ground at the edge of the clearings, and strain their eyes for moments when they could catch a glimpse of the enemy. The fierce heat from the sun was intolerable - and water was almost impossible to obtain.

Jacob Kreps related: "Occasionally, the defenders stood upright in their trenches and parapets in order to fire volleys. At other times their rifle pits appeared dotted with straw hats - and a moment later,the enemy was invisible again. Our soldiers would shoot the hats to pieces but did not kill anyone. The Spaniards had resorted to the old trick of placing their hats on sticks for the men to shoot at. The blockhouse and trenches at the south end of town were protected by tall trees. Not only did they conceal the enemy's movements, but snipers stationed in the trees became a major problem. The sharpshooters could not be seen, however, their fire was devastatingly accurate."

Because of the two-mile range of the high-powered Mausers, the American artillery was useless at close distances against the Spanish defenses. The most frustrating aspect about the failure of artillery support was the fact that the gun batteries were unable to cover the infantry assaults on the San Juan heights and El Caney adequately........

M93 Spanish Mauser

At the same time that Chaffee's troops were assaulting the hilltop, Ludlow's brigade - led by the 22nd Infantry Regiment - rushed from their jungle cover and sprinted across the fire-swept clearing. Yard by yard, trench by trench, and blockhouse by blockhouse, the brigade fought its way into the town. The Spanish garrison was besieged on all sides. The enemy became confused and disoriented. They searched for a route to withdraw their forces to the safety of Santiago, but there was only one path still open - the Cuabietas road.

Captain Lockwood's Second Battalion had been waiting all afternoon to get into the fight. They could hear the battle raging, but had no idea of the outcome until Spanish soldiers were seen fleeing toward them. Very few, if any, of the enemy escaped Lockwood's ambush. More than two hundred dead and wounded were counted along the intended retreat route. Captain Wassell recalled the moment of triumph: "We heard shouting from the hill. At first we did not comprehend the reason for the celebration but as the sounds rose in volume, we realized that they were American voices cheering their victory."

The Fifth Army Corps casualties for the one-day battle at San Juan Heights and El Caney totaled 200 dead and nearly twelve hundred wounded. The 22nd Infantry Regiment was saddened by the news that Colonel Wikoff had been killed earlier in the day at San Juan Hill. Of the twenty-four 22nd Infantry Regiment officers in the battle, six had been wounded. Of four hundred and thirty-six enlisted men, nine had been killed and thirty-five wounded.

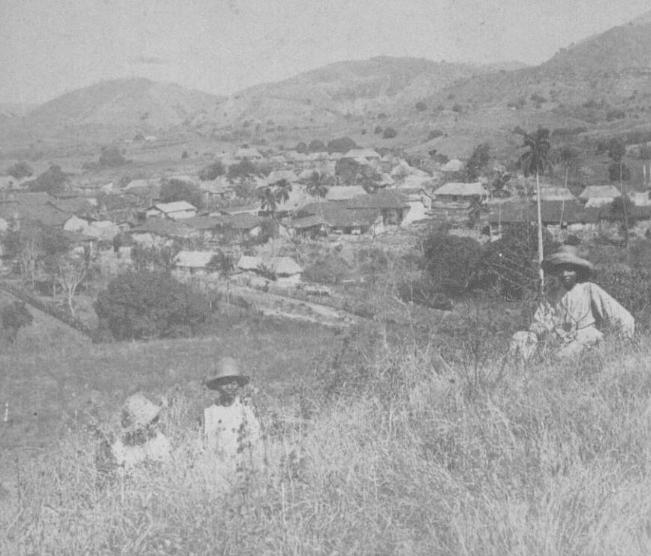

The town of El Caney, as seen from the Spanish fort of El

Viso

The weary soldiers of the 22nd Infantry had hoped for a good meal and a few hours' rest - but it was not meant to be. During the early morning march to El Caney, the troops had been ordered to stack their haversacks and blanket rolls at different locations along the road. The belongings were placed under guard. However, a few hours later, when the walking wounded began straggling to the rear, the surgeons called upon the sentries to help bring the injured men to the aid station. Two miles of blankets, ponchos, and rations were left unguarded, and anyone who passed along the trail helped themselves to whatever they happened to need.

After the conflict, when the Regiment returned to pick up their belongings, very little was left. About six o'clock, rain started to fall, and the dead tired soldiers - without having eaten, and no blankets or ponchos to keep themselves dry - laid down alongside the muddy roadway - and slept.

At three o'clock the following morning, July 2, Lawton's division was ordered to head for Santiago. His brigades were harassed by snipers during the march, but managed to reach their assigned positions on schedule. The string of American trenches stretched in a five-mile horseshoe curve around the city. The 22nd Infantry dug themselves in on the extreme right of the line. At 10:30 that night, the Spaniards launched an artillery barrage and infantry against the right flank of the division. The 22nd Infantry Regiment held their ground and beat back the enemy charge. Casualties in the Regiment were two killed and two wounded.

The Regiment earned the honor of writing in its history the following congratulatory orders, necessarily issued later, but bearing solely on the fight of July 1:

"The Brigadier General Commanding desires to congratulate the officers and men of this command on the gallantry and fortitude displayed by them in the investment and capture of Caney on Friday, July 1st.

Infantry attacks on fortified positions well defended are recognized as the most difficult of military undertakings, and are rarely successful. The defense was conducted with admirable skill behind an elaborate system of blockhouses, intrenchments and loop holes. Nevertheless, after a stubborn and bloody combat of nearly eight hours, the place was taken and its garrison practically annihilated. The exploit is the more notable that the affair was entered upon and carried through by men most of whom had never been under fire. The high percentage of casualties shows the severity of the work; 14% of loss among the officers and 8% of the enlisted forces. This action, though relatively of minor importance, will take its place as one of the conspicuous events in military history, by reason of its success under conditions of great difficulty, and all who contributed toward the achievement have reason for present and future congratulations."

By Command of Brigadier General Ludlow

After the battle of El Caney, US officers inspect the

battlefield

The destroyed Spanish fort, El Viso, looms in the background

Actions of July 3 through July 18, 1898:

The 22nd Infantry held their position through the remainder of July 2 and 3. Dr. Dunham recorded the tragic set of circumstances that were about to occur - and would take more American lives than the war itself: "When the notice of the bombardment was sent to General Torah, the city gates were opened and thousands of miserable inhabitants rushed out toward the invading corps. They were received with compassion and kindness - which did more credit to the hearts of our men than to their heads. The rabble were hungry, and stricken with disease and infection. They were truly more menacing to the Americans than all the soldiers of Spain."

The chief surgeon, Lieutenant Colonel Senn, stated: "Our troops were in a strange land among strange people. The Americans enjoyed the novelty of hero worship - not realizing how dearly they would be called upon to pay for such a privilege. Houses and huts in which yellow fever was raging were visited regularly, and the dangerous germs of this and other diseases were inhaled as a matter of course. The results of such intimate association by our susceptible soldiers with the natives could not be readily foreseen. It required only the usual time for the disease to make its appearance. And when it did so, it was everywhere along the lines of entrenchment's."

On the morning of July 4, the 22nd Infantry was ordered into position three miles farther to the right and closer to the besieged city. During the night, the 22nd Infantry Regiment was moved forward to the northeast point of Santiago Bay - less than two hundred yards from the enemy rifle pits. Captain Wassell stated: "We were so close to the Spaniards that we could yell at each other. Some of our men could speak Spanish, and many verbal exchanges took place - usually ending in mutual cursing."

However, the lengthy siege was beginning to take its toll on the Fifth Army Corps. General Marcus Wright observed: "The men had been standing day and night crouched in the trenches - often knee deep in water from thunderstorms, and always short on rations. The oppressive heat and sickness was having a detrimental effect on the troops. They were unprotected from the drenching rains, and fell easy prey to tropical diseases. Morale was low, and every day it became more difficult to arouse them to vigorous action." The troops maintained their positions amid the terrible conditions and finally, on July 16, the final terms of the Spanish surrender were agreed upon.

After General Shafter and men of the 2nd Cavalry and 9th Infantry Regiments entered Santiago, the celebration began in the Fifth Corps rifle pits. Jacob Kreps described the joyous scene: "The 22nd Infantry and their band paraded in perfect formation along the battlefront. As far as the eye could see, solders were jumping about on the crests of the trenches, celebrating their hard won victory. The surrounding hills were alive with frolicking troops - and brightly colored regimental and American flags dotted the landscape. On the following day, July 18, the Regiment was moved back to San Juan Heights. Everyone was suffering from unavoidable exposure. During the daily thunderstorms, the men had only been able to get slight protection from their shelter halves. For many days and nights they had worn the same wet clothing and slept in water filled trenches. Malaria, yellow fever, typhoid, and dysentery spread through the Regiment until only a few officers and a small number of men were fit for duty - and these only because they were less sick than the others."

Disease and Return to the States:

No matter how hard the medical department worked to save lives, the soldiers continued to succumb to the tropical illnesses at an alarming rate. General Shafter held a meeting with his division and brigade commanders. It was unanimously decided that the only salvation for the troops was to leave Cuba as soon as possible. The Regiments would be replaced with men from southern states - who were thought to be immune to yellow fever.

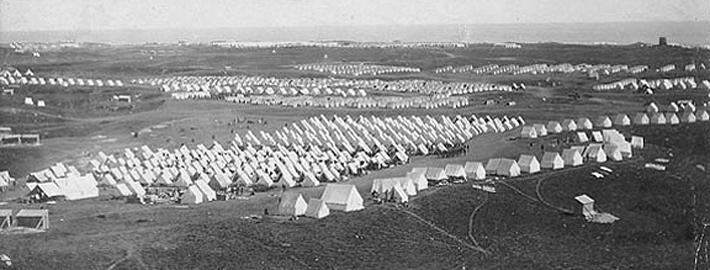

The Surgeon General selected Montauk Point, New York as the campsite for the returning American soldiers. It was located at the extreme eastern end of Long Island and thought to be far enough away from populated areas for safety. The receiving station was named Camp Wikoff in honor of the 22nd Infantry's popular colonel. As the American troops boarded the transports for their trip back to the United States, they were issued summer uniforms - just in time for the sharp sea breezes and chilly nights at Montauk Point.

General Ludlow's brigade, including the 22nd Infantry Regiment, was notified on August 11, 1898 that they were to return home aboard the Mobile. The troops were inspected by medical officers for signs of yellow fever. All infected clothing was burned, and summer uniforms issued. The brigade embarked on August 13. Jacob Kreps wrote: "The journey from Cuba to the United States added more hardships to the Regiment's already long list. No provisions had been made for the sick. Men suffering from fever, chills,and various stomach ailments, were compelled to eat ordinary rations. Eleven deaths occurred during the trip. We reached Montauk Point on August 20. But by now the news of the dreadful campaign, and the appalling stories of the ocean voyages, had reached the American public. Privations were now a thing of the past. The people seized every opportunity to load upon the returning soldiers all the delicacies of life. Nothing was left undone, by the government or private citizens, that could add to the comfort - and the luxury - of the troops. And although the majority of the men were prevented by sickness from enjoying the many good things thrust upon them, the kindness prompting these gifts cheered more than one invalid to recovery."

Camp Wikoff

On September 16, 1898, the 22nd Infantry Regiment left Camp Wikoff for its former station - Camp Crook, Nebraska. Out of the 513 officers and men who had left the post four months earlier, only 165 returned - and almost all of those were still suffering from disease and malnutrition.

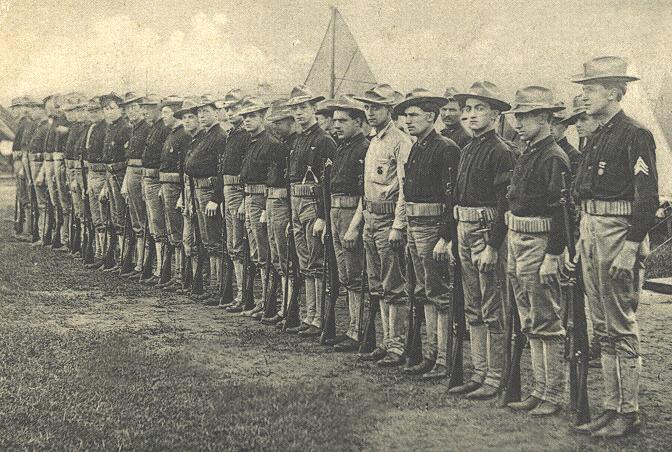

Upon the 22nd's return to Nebraska, four additional companies were authorized - bringing the Regimental strength to twenty-six officers and 1,070 enlisted men. Jacob Kreps was advanced in rank to captain and appointed commanding officer of Company M. However, nearly the entire Regiment was now comprised of new recruits. It would take four months of intensive training before the 22nd Infantry Regiment would be prepared to be sent into action again - and they were again on the road to war when they received orders on January 27, 1899 to proceed to California by rail for embarkation to the Philippines.

Company L 22nd Infantry, Sea Girt, New Jersey - 1898

Campaign Medal for Spanish American War

Home | Photos | Battles & History | Current |

Rosters & Reports | Medal of Honor | Killed

in Action |

Personnel Locator | Commanders | Station

List | Campaigns |

Honors | Insignia & Memorabilia | 4-42

Artillery | Taps |

What's New | Editorial | Links |