¹

¹

¹

¹

David Sloane Stanley

Commanding Officer 22nd Infantry

1866-1884

The 22nd Infantry Regiment did

not exist during the Civil War. After the War in 1866 the 22nd

Infantry was re-activated

from elements of the 13th Infantry. COL David Sloane Stanley was

the 22nd's first Commander after the re-activation.

He commanded the 22nd Infantry for eighteen years.

Below are the listings for David

S. Stanley in the Official Army Registers

including his Regular Army service and concurrent service in the

Volunteers.

At the same time that Stanley was occupying General positions in

the Volunteers

and leading troops as a General he still held lesser actual rank

in the Regular Army:

Cadet Military Academy

................................................ July, 1, 1848

Brevet 2nd Lieutenant 2nd Dragoons

............................... July 1, 1852

2nd Lieutenant

...................................................... September

6, 1853

Transferred to 1st Cavalry

........................................... March 3, 1855

1st Lieutenant

............................................................

March 27, 1855

Captain 4th Cavalry

................................................... March 16,

1861

Offered Brigadier General of Volunteers .............. September

28, 1861

Accepted Brigadier General of Volunteers ............... October

15, 1861

Offered Major General of Volunteers ................... November

29, 1862

Accepted Major General of Volunteers ........................

April 10, 1863

Major 5th Cavalry

................................................. December 1,

1863

Shot in the neck at the Battle of Franklin, Tenn.......November

30, 1864

Awarded Brevet as Major General .............................

March 13, 1865

Honorably mustered out of the Volunteers ............... February

1, 1866

Offered Colonel 22nd Infantry

....................................... July 28, 1866

Accepted Colonel 22nd Infantry ..........................

September 13, 1866

Offered Brigadier General

.......................................... March 24, 1884

Accepted Brigadier General

......................................... April 18, 1884

Retired

...........................................................................

June 1, 1892

Awarded the Medal of Honor for actions in 1864..........March 29,

1893

Died.............................................................................March

13, 1902

At his retirement Stanley was the fourth highest ranking General in the United States Army.

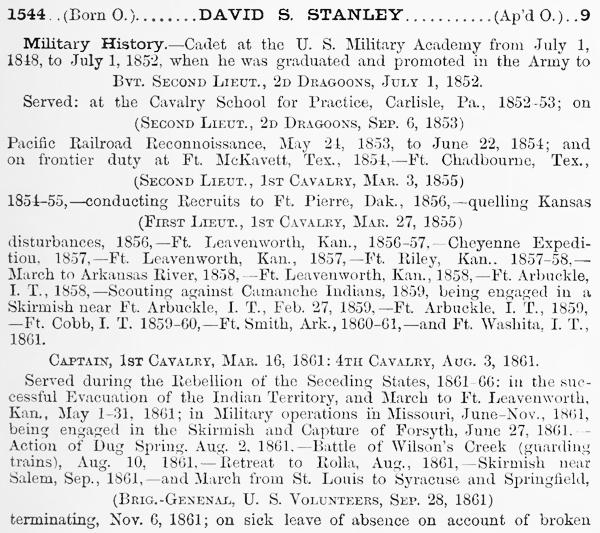

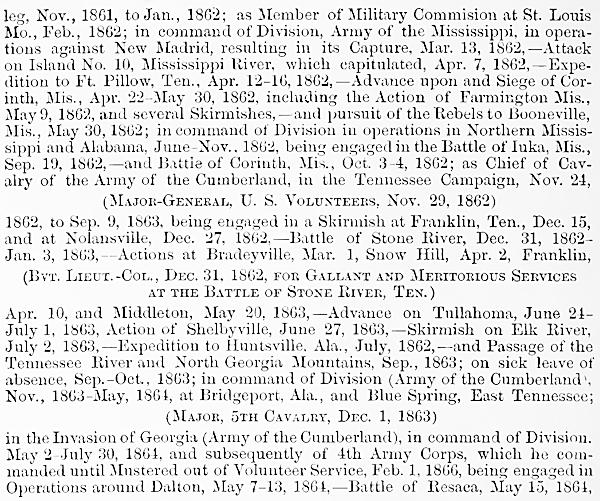

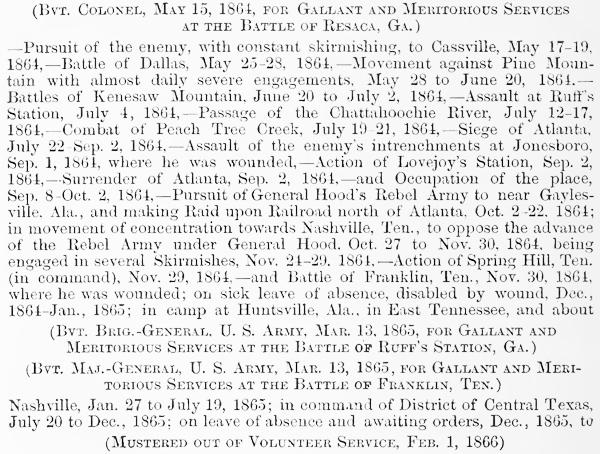

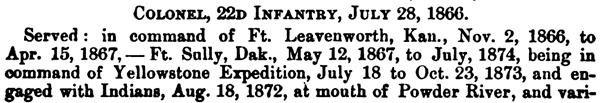

The following is the military

history of David Sloane Stanley as

recorded in Cullum's Registers, published 1868 through 1901:

As Commander of the 22nd

Infantry Stanley led three expeditions into the Yellowstone

country of Montana

during the years 1871-1873. These were the first attempts at

exploring and mapping this still wild and unknown

country. The most important of these expeditions was the one in

1873. On that expedition Stanley commanded

a force consisting of eighteen companies of infantry (comprised

of the 8th, 9th, 17th and 22nd Infantry), and

ten companies of cavalry. The cavalry was the 7th Cavalry under

LTC George Custer who reported directly

to Stanley. Expeditions into the Yellowstone were resisted and

harrassed by Sitting Bull and the Sioux with

several engagements being fought, as preludes to the great Sioux

Wars of 1876-1877.

To read Stanley's 23 page report

of the 1873 expedition click on the link below.

(The link is to a PDF file. To return to this page click the

"back" arrow in the PDF file.)

Below are three biographies of

David S. Stanley, each with something

unique to say about him:

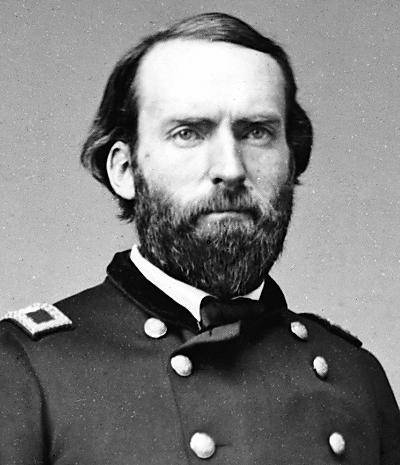

David S. Stanley

No specific date given

for the above photo, only the vague date of between 1860-1870.

The rank insignia in his shoulder board is indeterminable,

however, it is a single insignia,

indicating the photo was taken prior to his position of Major

General of Volunteers in 1863.

Library of Congress photo number LC-DIG-cwpb-04715

STANLEY, David Sloan, soldier, born in Cedar Valley, Ohio, 1 June, 1828. He was graduated at the United States military academy in 1852, and in 1853 was detailed with Lieutenant Amiel W. Whipple to survey a railroad route along the 35th parallel. As lieutenant of cavalry from 1855 till his promotion to a captaincy in 1861, he spent the greater part of his time in the saddle. Among other Indian engagements he took part in one with the Cheyennes on Solomon's Fork, and one with the Comanches near Fort Arbuckle.

At the beginning of the civil war he refused high rank in the Confederate army. In the early part of the war he fought at Independence, Forsyth, Dug Springs, Wilson's Creek, Rolla, and other places, and was appointed brigadier-general of volunteers, 28 September, 1861. He led a division at New Madrid, and the commanding general reported that he was "especially indebted" to General Stanley for his "efficient aid and uniform zeal." Subsequently he was complimented for his "untiring activity and skill" in the battle of Island No. 10. He took part in most of the skirmishes in and around Corinth and in the battle of Farmington. In the fight near the White House, or Bridge Creek, he repelled the enemy's attack with severe loss, and he was especially commended by General William S. Rosecrans at Iuka. At Corinth he occupied the line between batteries Robinett and Williams, and was thus exposed to the severest part of the attack of the enemy, and, although other parts of the line gave way, his was never broken. General Stanley was appointed major-general of volunteers on 29 November, 1862. He bore an active part in most of the battles of the Atlanta campaign, and as commander of the 4th army corps he took part in the battle of Jonesboro'. After General George H. Thomas was ordered to Nashville, General Stanley was directed on 6 October to command the Army of the Cumberland in his absence. Until he was severely wounded at Franklin, he took an active part in all the operations and battles in defence of Nashville. His disposition of the troops at Spring Hill enabled him to repel the assault of the enemy's cavalry and afterward two assaults of the infantry. A few days afterward, at Franklin, he fought a desperate hand-to-hand conflict. Placing himself at the head of a reserve brigade, he regained the part of the line that the enemy had broken. Although severely wounded, he did not leave the field until long after dark. When he recovered he rejoined his command, and, after the war closed, took it to Texas.

He had received the brevets of lieutenant-colonel for Stone River, Tennessee, colonel for Resaca, Georgia, brigadier-general for Ruff's Station, Georgia, and major-general for Franklin, Tennessee, all in the regular army. He was appointed colonel of the 22d infantry, and spent a greater part of the time up to 1874 in Dakota. In command of the Yellowstone expedition of 1873, he successfully conducted his troops through the unknown wilderness of Dakota and Montana, and his favorable reports on the country led to the subsequent emigration thither. In 1874 he went with his regiment to the lake stations, and in 1879 moved it to Texas, where he completely suppressed Indian raids in the western part of the state. He also restored the confidence of the Mexicans, which had been disturbed by the raid that the United States troops made across the boundary in 1878. He was ordered to Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 1882, and placed in command of the district of New Mexico. While he was stationed there, and subsequently at Fort Lewis, complications arose at various times with the Navajos, Utes, and Jicarillas, all of which he quieted without bloodshed. The greater part of his service has been on the Indian frontier, and he has had to deal with nearly every tribe that occupies the Mississippi and Rio Grande valley, thus becoming perfectly acquainted with the Indian character. In March, 1884, he was appointed a brigadier-general in the regular army, and assigned to the Department of Texas, where he has been ever since.

(From a volume published in 1899)

Edited Appletons Encyclopedia, Copyright © 2001 VirtualologyTM

http://www.famousamericans.net/davidsloanstanley/

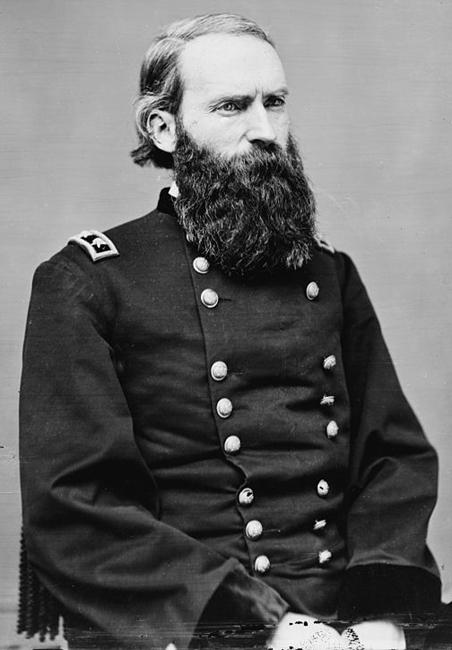

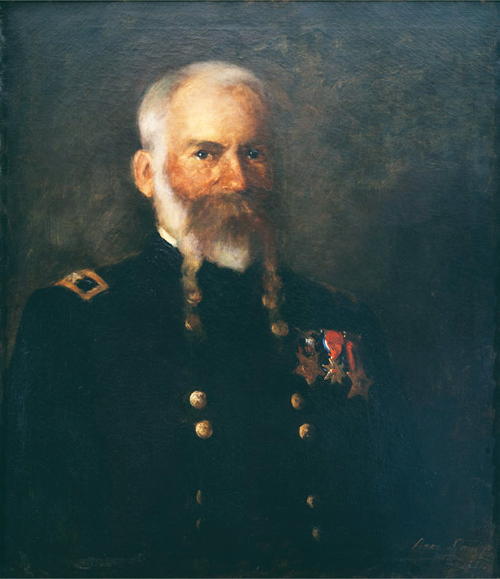

A portrait of Stanley taken during the

Civil War

in his uniform of Major General of Volunteers

Thanks to Thomas A. Broido for the identification of the above photo

David Sloan Stanley was born on 1 June 1828 and entered service at Congress, Wayne County, Ohio.

Commissioned in the 2nd Dragoons

in 1852 as young officer Stanley spent considerable time in the

west.

The outbreak of the Civil War found Stanley in Missouri where in

1861 he participated in an early engagement

at Wilson's Creek near Independence, Mo. Appointed a Brigadier

General of Volunteers he commanded a

cavalry division in the Stone River Campaign and was brevetted

for gallantry at the Battle of Murfreesboro.

Stanley led a corps in the Chickamauga Campaign.The year 1864

found Brigadier General Stanley serving as

the Chief of Cavalry for the Army of the Cumberland. On November

30, 1864 at the Battle of Franklin, at a

critical moment rode to the front of one of his brigades,

reestablished its lines, and gallantly led it in a

successful assault. He would later be awarded the Medal of Honor

for his gallantry in action.

Wounded in this action, he was brevetted a total of four times

during the war.

The citation for David S. Stanley's Medal of Honor reads:

Rank and organization: Major General, U.S.

Volunteers.

Place and date: At Franklin, Tenn., 30 November 1864.

Entered service at: Congress, Wayne County, Ohio.

Born: 1 June 1828, Cedar Valley, Ohio.

Date of issue: 29 March 1893.

Citation: At a critical moment rode to the front of one of his brigades, re-established its lines, and gallantly led it in a successful assault.

After the war, Stanley returned

to the west where he first served as the commander of the

occupying force

at San Antonio in 1866. He later served as the commander of the

22nd Infantry against hostile Indians.

During this period while skirmishing against the Sioux he had an

interesting encounter with another Civil War

cavalry officer, LTC George Armstrong Custer, destined for a

precarious place in US History. General Stanley

had to officially reprimanded Custer while under his command for

a series of offences including marching 15 miles

away from the rest of a column without orders. In what was an

almost farcical act, Custer was ordered to get rid

of a cooking stove no less than six times by Stanley who became

totally exasperated with him in much the same kind

of way Custer's West Point superiors and fellow officers during

the Civil War must have been.

In 1884, General Stanley was appointed commander of the

Department of Texas with its Headquarters at

Fort Sam Houston. During his tenure at Fort Sam Houston, the post

was enlarged to become the second largest

Army post in the US. General Stanley passed away in 1902. In

October 1917, War Department General Order #134

designated Camp Stanley near San Antonio in his honor.

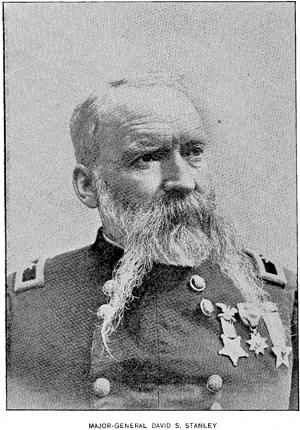

Stanley, after he retired, in his full

dress uniform.

One of the very few photos taken of him wearing his Medal of

Honor.

His medals, left to right, are:

Medal of the Society of the Army of the Cumberland, Medal of

Honor,

Medal of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United

States,

Medal of the Grand Army of the Republic

STANLEY, DAVID SLOANE (1828–1902).

David Sloane Stanley, United

States Army officer, was born in Cedar Valley, Ohio, on June 1,

1828, the son of John Bratton

and Sarah (Peterson) Stanley. He was appointed to the United

States Military Academy at West Point on July 1, 1848.

He graduated ninth in the class of 1852, of which his close

friend Philip H. Sheridan was a member, and was brevetted

second lieutenant in the Second United States Dragoons on July 1

and assigned as quartermaster to Lt. Amiel W. Whipple's

surveying party, which charted the route of a railroad from Fort

Smith, Arkansas, to San Diego, California. Stanley was

promoted to the substantive grade of second lieutenant on

September 6, 1853. In 1854 he was ordered to Fort Chadbourne

on the Texas frontier. He was transferred to Capt. George B.

McClellan's Troop D of the First United States Cavalry on

March 3, 1855, and was promoted to first lieutenant on March 27.

In 1856 he was sent with his regiment to Kansas to

quell the disturbances there between proslavery advocates and

"free soilers." On April 2, 1857, he married Anna Maria

Wright,

whom he had first met while he was a cadet at West Point; the

couple had seven children. After service against the

Cheyenne Indians on the Great Plains, in which his life was saved

by J. E. B. Stuart in a fight near Fort Kearny,

Nebraska, he was assigned to Fort Smith, Arkansas, in 1860. He

was promoted to captain on March 16, 1861, and

transferred to the Fourth United States Cavalry on August 3. At

the outbreak of the Civil War Stanley, himself a slaveowner,

was offered a colonel's commission in the Confederate Army and

command of an Arkansas regiment, but he declined

the offer and joined other Union forces at Fort Leavenworth,

Kansas. He was appointed a brigadier general of volunteers

on September 28, 1861. He fought in the battles of Wilson's

Creek, New Madrid, and Island Number Ten in the Missouri

campaign of 1862. In consequence of his good work at the battle

of Corinth, Mississippi, in October 1862 he was promoted

to major general on November 29 and appointed chief of cavalry of

the Army of the Cumberland. Stanley was brevetted

to lieutenant colonel in the regular army on December 31 of the

same year for "gallantry and meritorious service"

at the battle of Stone River, Tennessee; to colonel on May 15,

1864, for his role in the battle of Resaca, Georgia; and

to brigadier general on March 13, 1865, for his part in the

action at Ruff's Station, Georgia. He was severely wounded

at the battle of Franklin, Tennessee, on November 30, 1864, in

which he commanded the Fourth Corps of Maj. Gen.

George H. Thomas's Army of the Cumberland. For his

"distinguished bravery" at Franklin he was brevetted to

major general

on March 13, 1865, and awarded the Medal of Honor on March 29,

1893. He was posted to the Fifth United States Cavalry

as a major in the regular army on December 1, 1863. He was

mustered out of volunteer service on February 1, 1866,

and promoted to colonel of the Twenty-second United States

Infantry on July 28, 1866.

After recovering from his wound, Stanley led the Fourth Corps

into Texas in June 1865 to counter growing French

involvement in Mexican internal affairs and the threat posed by

the emperor Maximilian. He debarked at Indianola and

established his headquarters at Victoria, where he found the

weather "very warm and tiresome" but enjoyed the

companionship of John J. Linn. In October he moved his

headquarters to San Antonio; there he remained until the last

of his regiments was mustered out of service in March 1866. By

this time, Stanley admitted, his men "were not happy and

discipline none too good." While commandant at San Antonio,

he ordered the sale to a circus of the remaining camels

from Camp Verde, thus bringing to an end the United States Army's

camel corps experiment. In 1866 he was back on the

Indian frontier; in 1873 he was involved in the Yellowstone

expedition, and from 1879 through 1882 he was involved in

suppressing various Indian uprisings in Texas. On March 24, 1884,

upon the retirement of Ranald S. Mackenzie, Stanley

was promoted to brigadier general in the regular United States

Army and named commander of the Department of Texas.

He retired on June 1, 1892. From September 13, 1893, until April

15, 1898, he was governor of the Soldiers' Home

in Washington, D.C. General Stanley died in Washington on March

13, 1902, and was buried in the Soldiers Home cemetery.

His autobiography, Personal Memoirs of Major-General D. S.

Stanley, U.S.A., published in 1917, contains many colorful

pictures of service on the Texas frontier. From 1917 to 1947 Camp

Stanley, a military installation near San Antonio,

was named in honor of the general.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Francis B. Heitman, Historical Register and Dictionary of the

United States Army (2 vols., Washington: GPO, 1903;

rpt., Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1965).

Vertical Files, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History,

University of Texas at Austin.

Ezra J. Warner, Generals in Blue (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State

University Press, 1964).

Thomas W. Cutrer

Thomas W. Cutrer, "STANLEY, DAVID

SLOANE," Handbook of Texas Online (http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fst12),

accessed April 27, 2014. Uploaded on June 15, 2010. Published by

the Texas State Historical Association.

David Sloane Stanley was an

Original Companion of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of

the United States,

a member of the Grand Army of the Republic, a member of the

Executive Committee of the Society of the

Army of the Cumberland, a member of the National Society, Sons of

the American Revolution

and an Honorary Companion of the Military Order of Foreign Wars.

David Sloane Stanley's decorations

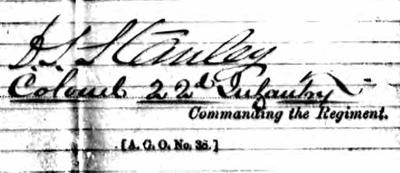

The signature of David S. Stanley as

Commanding Officer 22nd Infantry

on the monthly Return of the 22nd Infantry for September 1875.

David Sloan Stanley

Oil on canvas, 31 ½ x 27 ¾ in.

c. 1890, Fort Sam Houston, San Antonio, Texas

Signed lower right; Anna Stanley 1890

Private Collection, Washington, DC

"This portrait of the artist’s father, aged sixty-two,

was painted after she studied for two years in Europe. The

painting was completed

near the end of her father’s service as the commanding

general of the Texas Territory at Fort Sam Houston. Anna returned

to Texas,

in November 1889 where this was likely painted. Although the

portrait is formal and a departure from her impressionist style,

she confers on her father the deference that his place in history

deserved as a Medal of Honor recipient."

From the Smithsonian website

(1st Battalion Website Editor: This is

one of two portraits of her father done by Anna Stanley.

This portrait hangs in the Army and Navy Club, 901 17th Street,

Washington, District of Columbia 20006)

Below is the incredibly long

eulogy for Stanley written for the Annual Reunion of Graduates of

West Point

by an unknown classmate of Stanley. It is reprinted here in its

entirety.

²

²

DAVID SLOANE STANLEY.

No. 1544. CLASS OF 1852.

Died, March 13, 1902, at Washington, D. C., aged 74.

DAVID SLOANE STANLEY was born

June 1, 1828, at Chester, Cedar Valley, Wayne County, Ohio. His

father was a farmer.

After the death of his parents he studied medicine under Dr.

Firestone, at Wooster, Ohio, but gave up that study when he

received his appointment as a cadet. He was a son of John Bratton

Stanley and Sarah (Peterson) Stanley; great grandson of

Marshall Stanley; great (2) grandson of Nathaniel Stanley,

private Spencer's Connecticut regiment in the War of the American

Revolution, and a grandson of Conrad Peterson, private Virginia

line. He married, April, 1857, Anna Maria Wright,

daughter of General Joseph Jefferson B. Wright, Assistant Surgeon

General United States Army, and to them were born

seven children—Florence, Josephine, Sarah Elizabeth, Anna

Huntington, Alice, Blanche Huntington and David Sheridan.

Elizabeth and Anna married, respectively, Captains David J.

Rumbough and W7illard A. Holbrook, United States Army.

The father's ancestors came from Lancastershire, England, and

settled in Connecticut about 1650, in the neighborhood of

New Britain. Later a part of the family removed to Pennsylvania

and Ohio. The mother's family were of Coventry, Connecticut,

subsequently of Wilkesbarre, Pennsylvania, where the family

resided for several generations. Mrs. Stanley's grand-uncle was

Samuel Huntington, a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

The children, by ancestral blood of their father and mother,

are connected with the War of the American Revolution, as follows

: Grandchildren of John Bratton and Sarah (Peterson)

Stanley; great grand-children of William and Margaret (Bratton)

Stanley; great (2) grand-children of Marshall and Thamor

Stanley; great (3) grand-children of Nathaniel Stanley, private

Spencer's Connecticut regiment; great grand-children of

Conrad Peterson, private Virginia line; grand-children of Joseph

Jefferson B. and Eliza (Jones) Wright; great grand-children

of Amasa and Elizabeth (Huntington) Jones; great 2grand-children

of Joel Jones, Lieutenant Colonel Connecticut militia.

From 1852, when Stanley

graduated with distinction at West Point, to 1884, he passed

through all the grades, in the

regular service, from Second Lieutenant, by brevet, to Brigadier

General, excepting that of Lieutenant Colonel; and in the

volunteer service he was among the earlier Brigadier Generals,

reaching the grade of Major General in November, 1862,—

in all ten commissions. In addition, he received in the regular

army four commissions, by brevet: Lieutenant Colonel,

December 31, 1862, for gallant and meritorious services at the

battle of Stone River; Colonel, May 15, 1864, for gallant

and meritorious services at the battle of Resaca; Brigadier

General, March 13, 1865, for gallant and meritorious services

at the battle of Ruff's Station; and Major General, March 13,

1865, for gallant and meritorious services at the battle

of Franklin. His distinguished labors embraced numerous

skirmishes, actions, expeditions, pursuits and battles.

He commanded companies,

regiments, brigades, divisions, an army corps, districts and

departments. He was appointed

Chief of Cavalry, Army of the Mississippi, in Dec., 1863; and

subsequently Chief of Cavalry, Army of the Cumberland,

wherein he commanded the cavalry, with special distinction, in

the Stone River, Tullahoma and Chickamauga campaigns.

He received the Congressional Medal of Honor for distinguished

bravery at the battle of Franklin, where he was severely

wounded while commanding the Fourth Army Corps. In that battle,

"when he discovered the break in the (Union) line,

although a Corps Commander, he placed himself at the head of a

brigade, and, leading the charge, drove the enemy back,

and re-established the continuity of the line."

On June 1, 1892, he was retired

from active service, being 64 years of age. On September 13,

1893, he was assigned,

by the President, as Governor of the National Soldiers' Home,

Washington, D. C, and so served until April 15, 1898,

when he resigned the position.

Prior to the secession of Texas,

the military department embracing that State was a most important

command,

"almost five-sixths of the whole army and field batteries of

the nation." That force was surrendered by the

department commander, and, as a part of it, the First United

States Cavalry—subsequently the Fourth—with

Captain Stanley commanding the companies in the field. Stanley

refused to recognize the surrender, and promptly

ordered the regiment to Forts Arbuckle and Washita, Indian

Territory, and Fort Wise, Colorado Territory; and thus

prepared to defend his honor, during March and April, 1861,

"against not only the hostile arms, but the more

dangerous seductions of the" insurgent emissaries. In May,

leaving four companies at Fort Wise, he moved, six to

Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and in June actively skirmished through

Missouri and Colorado. In late July he commanded

the cavalry attached to Brigadier General T. W. Sweeney's force,

and attacked the greater part of General Price's

Confederate force, at Forsyth, Missouri. For some hours the

conflict was doubtful, until Stanley, at the head of four

companies of his regiment, charged the center and cut through,

capturing two pieces of artillery and many prisoners,

utterly routing the Confederate force, which, demoralized,

retired into Arkansas, losing through desertion about 5,000 men.

In the charge Stanley's horse was shot.

On July 25, while commanding the

cavalry in the Army of the Missouri, he led 250 men, including 40

volunteers, in the

charge upon the Confederate rear guard, at Springfield, with the

result that the entire rear guard, over two thousand, was

destroyed.

On August 2nd, his dash and bravery were again attested, at Dog

Spring, Missouri. On August 3, in recognition of his most

valuable services, he was assigned to the command of the Fourth

Cavalry, the designation given by Congress to the former

First Regiment. He was in the battle of Wilson's Creek, guarding

supply trains, August 10, 1861; retreat at Rolla, August, 1861;

skirmish at Salem, September, 1861. September 28, 1861, he was

appointed Brigadier General United States Volunteers,

in recognition of his ability and distinguished services.

As the war advanced, the Fourth

Cavalry became a unit in the Second Cavalry Division, Army of the

Cumberland.

The instruction and elan given by Stanley to that noble regiment

proved of great value to it, as well as to the command

with which it served. That command "held a central position

in the grand field of the operations of the Armies of the Ohio,

the Cumberland and the Tennessee. * * * It received the surrender

of over 30,000 men and officers; captured over

80,000 stand of arms; nearly 20,000 horses, and took in battle,

by direct charge, 75 pieces of artillery, including

15 heavy siege guns; and, as a division, * * * captured the

second strongest fortified city in the Southern

Confederacy."

* * * "The cavalry arm of the service in the West, early in

the Civil War, developed and perfected into a mighty engine

of warfare, while in the East it was neglected, ridiculed,

dwarfed and stunted, until just before the final overthrow of the

enemy."

* * * In the East it was kept too much "within the leading

strings of the other arms of the service."*

NOTE.—"Minty and the

Cavalry," by Captain Joseph G. Vale, Brigade Inspector

United States Volunteer Cavalry.

That history of campaigns in the western armies refers,

frequently, to the services of General Stanley, and embraces a

valuable and interesting sketch of Stanley's services, by

Brigadier General John Green Ballance, late United States

Volunteer,

now Assistant Adjutant General, United States Army.

On August 31, 1864, during the

Atlanta campaign, the Fourth and Twenty-third Army Corps were too

far from the

main army to receive orders from General Sherman or General

Thomas, and despatches were received, from Sherman,

that the Fourth and Twenty-third Corps must act on the morrow,

under the orders of the highest commander present;

that General Stanley was that highest commander, and accordingly

General Schofield was directed to report to him.

Before Schofield had time to report, Stanley appeared at

Schofield's camp, evidently much disturbed by the order,

and said that Sherman was wrong; that he did not want the

command, and was not entitled to it, and, therefore, urged

Schofield to accept the chief command, thus that he might act

under Schofield's orders. Schofield replied that Sherman's

order was imperative, and that he could not relieve him from the

responsibility of executing it; it was all wrong, but

there was no present remedy. Later, at Lovejoy's, Sherman

requested Schofield to give him a written statement of his

dissent from the decision upon the question of relative rank. The

statement was submitted, by Sherman, to the War Department,

and in due time the decision by that department was rendered. It

sustained the view of the law as taken by Schofield and

Stanley, and reversed that of Sherman. As has been said, by

General Schofield, it was by virtue of that decision that he,

instead of Stanley, had command of the force that, in the

following November, 1864, opposed Hood's advance from the

Tennessee River, and repulsed his fierce assault at Franklin.

The incident illustrates

Stanley's well-founded magnanimity. Considering that the order

emanated from so distinguished

a soldier as Sherman, not every officer would have acted as

Stanley did. He went promptly to Schofield, who was his friend;

but had he been his enemy, he would have gone as promptly, for he

was ever actuated by greatness of mind, elevation and

dignity of soul, and disdained injustice, meanness and

revenge,—ever ready to act and sacrifice for noble objects.

At Spring Hill—where

Stanley was attacked by cavalry as well as

infantry—Schofield confidently trusted Stanley's

one division to hold that place until the army should reach it.

Schofield has said: * * * "The serious danger at Spring Hill

ended at dark. The gallant action of Stanley and his one division

at that place in the afternoon of November 29 cannot

be overestimated or too highly praised. If the enemy had gained a

position there in the afternoon which we could not have

passed round in the night, the situation would then have become

very serious. But, as I had calculated, the enemy did not

have time to do that before dark, against Stanley's stubborn

resistance." * * * Schofield has often referred to Stanley

as

"conspicuous for gallantry at Spring Hill, and at Franklin,

where he was wounded."

At Spring Hill he made temporary

cover for his troops with intrenching tools, improvised for the

most part on the spot,

by splitting the canteen of every other man and using the parts

as scoops to throw up the earth.

He fought at Franklin on three

occasions : the skirmish there December 15, 1862; the action

there April 10, 1863,

and the momentous battle there November 30, 1864.

His marked courage was

established early in his military career, notably in the Cheyenne

Indian campaign of 1857,

at the battle of Solomon's Fork, where White Antelope, the

celebrated Cheyenne chief, attacked him and snapped a pistol

in his face. The pistol, however, failed, and Stanley drew his

pistol and killed the Indian chief. It was a hand to hand

conflict !

At Forsyth, Mo., in June, 1861, he was in the thickest of the

fight, and his horse was shot from under him. In that engagement

he foreshadowed that eminent coolness, courage and gallantry

which ennobled his services from 1861 to 1865.

At Iuka, General Rosecrans

commended him for gallantry. He saved the day at that place; also

the day at Corinth.

Stanley ever had the highest respect for authority, and its

support, the moral order of the people. He prayed that the latter

might never be relaxed, so as to make necessary the government by

armies. And he held fast to the sublime enunciation that:

"Civil sovereignty is co-eval with men. The relations of

authority, submission and equality lie in the human family,

and from it are extended to commonwealths, kingdoms' and empires.

The civil authority resides materially in society

at large; formally in the person or persons to whom society may

commit its exercise. Immediately, therefore, sovereignty

is given by God to society; mediately through society to the

person who wields it. Both materially and formally,

mediately and immediately, sovereignty is from God, and within

its competence is supreme and sacred. Civil allegiance

to sovereignty is, therefore, a part of Christianity, and treason

is both a crime against lawful authority and a sin against God,

who has ordained that authority. * * * It is a part of the

Christian religion to obey "the powers that are." * * *

All nations

have their progress, and the progress of a nation is like the

growth of a tree, bearing its fruit in due season. If the trunk

of a tree be wounded, the vigor of the tree is stayed. Anything

which crosses the healthy development and growth, be it

a tree or human society, is fatal to its perfection." * * *

"The good and pure see God's power in the storm, in the

cataract,

in the earthquake. They see His wisdom in the laws which govern

the boundless universe; His beauty in the flower,

in the sun-beam, and in the many-tinted rainbow. But the wicked

and impure use this very creation only to outrage

and blaspheme the Creator."

Stanley advocated that the best

subjects are those who are first loyal to the creator of heaven

and earth;

and that they best keep the laws of the land who do it for

conscience sake.

He resolutely asserted that

loyalty is part of Christianity, and that "the time is

coming when true fealty, and true loyalty,

will be found only in those who are loyal and true, first to the

Heavenly King, and after this to the representatives of

his authority upon earth." * * * "Beware of

disobedience! Beware, also, not of actual disobedience only, but

of that

tardy slothful negligence by which one may provoke! Do your

little duties with great exactness; for if you will faithfully

do your lesser duties, your greater duties will take care of

themselves/" Nothing should be regarded as an accessory;

but everything as a principal.

The virtues necessary to command

shown eminently in Stanley, though not to the prejudice of true

zeal. In correcting faults,

he observed the well-stated rule: "Correction ought to be

full of sweetness, but yet strong enough to be effective and to

root out defects; it ought to have the softness of a silken

arrow, which does not penetrate; it should be of steel, but this

steel must be tempered in charity, which * * * can be piously

severe, patiently angry, and humbly indignant, —which

punishes,

but with chastisement full of mercy."

Early in Stanley's military

career he aided in the survey of a railroad to the Pacific, along

the thirty-fifth parallel. The route

became known as the Atlantic and Pacific, westward from

Albuquerque, New Mexico. Nineteen years afterward he organized

and commanded the Yellow Stone expedition, of 1872-73, to explore

and guard the Northern Pacific Railroad. His reports

of the latter expedition have proved valuable— they pointed

to the future population and wealth of what, at the time, was

almost an unknown region. It has been noted, as an interesting

coincidence, "that he should have been instrumental in

locating the routes of two great railroads." But his West

Point education fitted him for the tasks. His standing, number

nine,

in the large class of 1852, was distinguished,— number four

in engineering, five in mineralogy and geology, three in

chemistry,

seven in philosophy, and sixteen in mathematics. He had as

competitors such men as Casey, Alexander, Rose, Ives, Mendell,

Slocum, Bonaparte, Hascall, Mullan, Hartsuff, Woods, McCook,

Kautz, Crook, Sheridan, Bowen and others.

Stanley's distinguished services

are endurably recorded in the archives of the Department of War;

are outlined in

Cullum's register of the officers and graduates of our beloved

Alma Mater; and further outlined in the records of the

Congress of the United States through a report (No. 1245, 52d

Congress, 1st session) from the Committee on Military Affairs,

House of Representatives. Therein the following important battles

and actions, in which he well sustained a part, are enumerated:

Near Fort Arbuckle, Indian

Territory, February 27, 1859; Forsyth, Missouri, June 27, 1861;

Dug Spring, Missouri,

August 31, 1861; Wilson's Creek, Missouri, August 10, 1861; New

Madrid, Missouri, March 13, 1862; Island No. 10,

Mississippi River, April 7, 1862; Farmington, Mississippi, May

28, 1862; siege of Corinth, Mississippi, May 30, 1862;

Iuka, Mississippi, September 19, 1862; Corinth, Mississippi,

October 3-4, 1862; Franklin, Tennessee, December 15, 1862;

Stone River, Tennessee, December 31, 1862, to January 4, 1863;

Bradyville, Tennessee, February 13, 1863; Snow Hill,

Tennessee, March 10 and 30, 1863; Franklin, Tennessee, April 11,

1863; Middleton, Tennessee, May 22, 1863; Shelbyville,

Tennessee, June 27, 1863 ; Elk River, Tennessee, July 2, 1863;

Alpine, Georgia, September 9, 1863; Resaca, Georgia,

May 15, 1864; Cassville, Georgia, May 17-19, 1864; Dallas,

Georgia, May 15-28, 1864; Pine Mountain, Georgia,

May 28 to June 30, 1864; Kenesaw Mountain, Georgia, January 20 to

July 2, 1864; Rugg's Station, Georgia, July 4, 1864;

Peach Tree Creek, Georgia, July 19-21, 1864; siege of Atlanta,

Georgia, July 22 to September 2, 1864; Lovejoy's Station,

September 2, 1864; near Nashville, Tennessee, November 24-29,

1864; Spring Hill, Tennessee, November 29, 1864;

Franklin, Tennessee, November 30, 1864, (where he was wounded) ;

at the mouth of Powder River, Montana, August, 1872,

and a number of small skirmishes.

In the Congressional report, he

is referred to in communications from Generals Grant, Sheridan,

Schofield, Thomas,

Hancock, Pope, Howard, Augur, Crook and Terry, as a brave,

gallant and accomplished officer, serving through the Civil War

with conspicuous merit in the exercise of large commands,

contributing much to the successful overthrow of the war; as

fully

competent for all the requirements and responsibilities of his

position, evincing constant care as an efficient and faithful

commander;

as one noted for special skill, desperate fighting, able

generalship, and as possessing rare qualities eminently fitting

him to be a

leader of men.

"Some men are in pursuit of

honors; but others have honors in pursuit of them." Stanley

was of the latter class.

Following the views of eminent men as to the healthful solution

of important questions, Stanley-deprecated "a policy which

combines, in a most extraordinary way, the disadvantage, both of

yielding and of resistance, without gaining the advantages of

either course." And he believed that in the discharge of

duty "we must not go 'cap in hand' to the opponent."

But that we should go,

in order to good relations, "boldly with cap on head,"

* * * 'With hindward feather and with forward toe.'

Stanley's love for the United

States Military Academy was intense. His address to the

graduating class of 1885 was scholarly

and instructive, as part of a ceremonial which marked the

importance of the occasion when the cadet pathway was about to

join

the great rough roadway of the life so well known to officers of

the army. As stated by him, the class was to pass from tutelage

to that independence and freedom of life compatible with the

profession,of arms and the articles of war. Touchingly did he

add that the Superintendent and Academic Staff were not longer to

be their sponsors,—that thence forward future records would

be

mainly in their own hands. Through practical words, relative to

the origin, rise and perils of our Alma Mater, he made apparent

the rise and progress of the Academy, thereby to indicate

valuable results, with some hints to the end that the reputation

of the Academy might be kept true to its past history. He

referred to the War of the American Revolution, and the need

felt by its leaders relative to officers skilled in the science

of war, and then traced the Academy, from the efforts of the

Father of his Country, through the first official recognition and

ensuing steps, from 1790 to 1802, when, for the first time,

our Alma Mater had, in name, a legal existence. It continued to

grow in favor, and, in 1812, the part played by the graduates

was conspicuous and gallant,—they were well to the front;

one-half of them were either killed or wounded,—and in 1814

our flag floated in honor of numerous victories. He quoted the

words of Scott, the grand old hero: "But for our graduated

cadets, the war between the United States and Mexico might, and

probably would, have lasted four or five years, with, in its

first half, more defeats than victories falling to our share;

whereas, in less than two campaigns, we conquered a great

country,

and a peace, without the loss of a single battle."

Passing, briefly, the Indian

Wars and the great Civil War, Stanley referred to the action of a

select committee of the

House of Representatives, in 1837, which contemplated: * * *

"That all acts now in force authorizing the enlistment or

appointment of cadets * * * be, and are hereby repealed, from and

after the thirtieth day of June next; and all such cadets,

now in service or under the instruction of the United States,

shall be disbanded or dismissed." The select committee held

that constitutional principles, principles of sound policy, and

principles of fiscal economy, were opposed to certain features

of West Point. Great emphasis was rested on the

"unfruitfulness of the system of military education."

Repudiation was had

of the principle, held by many eminent statesmen, that "in

proportion as our own military establishment is small, the

government

ought to be careful to disseminate, by education, a knowledge of

the art of war; and that, in the event of war, the knowledge

of cadets who had returned to civil life will not be lost to the

country." And, after that repudiation, these words are

recorded:

* * * "Make it a known condition of filling up the army of

the United States, at any juncture of danger, that the citizen

soldier's

wishes are not to be consulted in the selection of your officers,

and that, so far from it, all his wishes and feelings are to be

violated by placing over him men whose education, habits,

temperaments and feelings, he has been accustomed to regard

with a feverish dislike, and what will be the consequence? Either

a failure in filling up the desired ranks, or the earliest

discharge

of their muskets will be to rid themselves of their obnoxious

commandants, and to devolve the duty of command

upon some more congenial comrade." * * *

The report ignored the views of

Presidents Washington, John Adams, Jefferson and Madison, and the

enunciations of

War Secretaries Dearborn, Crawford and Calhoun, aside from sound

words from other eminent statesmen. Stanley, in final

reference said: "So much for this wonderful report, which I

will dismiss by saying that ancient governments, whose armies

have filled the world with the splendor of victory, realized the

importance of discipline and military science; skill in the

individual officers; that science in war does more than force;

that neither numbers nor blind valor insure victory; and that he

who,

with a small army, could not execute great things, was liable to

be effaced from the list of great generals. Therefore, I may say

that the Moderns, who would have destroyed this institution, had

retrograded from the ancient teachings.

Fortunately for the Academy and

the country, our Presidents, their War Ministers and boards of

visitors, have not accepted

the erroneous theory that military science can be imbibed by

intuition, but, on the contrary, they have held that some

previous education is necessary to qualify a man to exercise the

art of war, and that mental, more than the physical,

qualities of man determine the issue of the contest. Further,

they have expressed the opinion that the Academy was the

basis of an army nucleus which would furnish the country with

well educated and trained officers, devoted to its service,

and capable of defending the frontiers, extending our

fortifications, carrying on great systems of internal

improvements,

guarding against the imposition of foreign peoples, and, above

all, of developing the undiscovered resources of great

states."

The "Tinsels of

Scholarship," so termed by a committee of Congress, have

proved to be, in the estimation of the country,

golden honors of unequaled brightness. * * It has been well said,

"that as the hills of the Hudson have constantly answered,

in faithful reverberations, to the sounds of the morning and

evening gun, so the hearts of the American people have

continually

responded, with equal fidelity, to every effort of the public

authorities for the inculcation of military science."

Stanley's further words, as to

all true officers, were: "From what I have said, as to our

graduates, do not understand me

as underrating the many distinguished officers of the army who

have been schooled in practical war, and, on that instruction

as a basis, have made themselves efficient officers. Nor do I

disparage the more youthful ones from civil life. All true

officers—

be they graduates or not—look to the acquirements and

character of the officer, and he is esteemed accordingly."

In the concluding part of his

address, in touching upon the future life of the class, he

embraced the following injunctions :

"It is one of the fundamental principles of government that

every citizen is bound to defend it when the necessity arises;

and

this principle applies much more strongly to you, whom the

country has educated. I beseech you to obey orders; be studious

in habit, and mark your duties with fidelity; observe strictly

the articles of war; owe no man,— live according to your

means;

and be not drinkers or gamblers. * * * Learn something every day.

* * * Read not as a matter of amusement, but to learn,

and as a matter' of duty and habit. Follow the advice of Carlyle,

to read into the very essence and core of books. * * * *

As a true guide to service in the army of your country, I beg

you, in the words of the illustrious Soldier of the Cross,

St. Paul, to 'be instant in season, out of season; reprove,

entreat, rebuke with all patience and doctrine. * * * Be thou

vigilant;

labor in all things; * * * fulfill thy ministry. Be sober.' So

that, as he has said, you may say at that solemn hour, which will

surely come : 'I have fought a good fight; I have finished my

course; I have kept the faith. For the rest, there is laid up for

me

a crown of justice, which the Lord, the just judge, will render

to me at that day.' "

The words of St. Paul, as

quoted, warrant me in saying that this sketch of Stanley would be

incomplete without an outline

of his religious life. In what I may say, I shall embrace

inculcation, familiar to Stanley, through quotation from

doctrinal writers.

Prior to his entrance to the

Military Academy, and for some years after his graduation, he

was, in religious belief, a Protestant.

The dangers of war had impressed him deeply, through his

experience in battle, and caused him to realize the nothingness

of this world, the shortness of earthly life and the duration of

eternity. Was he prepared for the latter? To this question

he gave the profound consideration which its importance demanded.

What would it avail should he gain the whole world and

lose his soul? His thoughtful attention to the subject led him to

the Catholic Apostolic Church; and in connection with that—

the most important step of his life— I have the following

from the Most Reverend John Ireland, Archbishop of St. Paul, who,

in the Civil War, was the Chaplain of the Fifth Minnesota

Volunteers: . . .

* * * "I myself had nothing

to do with his conversion, or his reception into the church. I

became acquainted with him only

a few weeks after he was received in the church. Father Tracey,

who had been, before the war, pastor of the church at

Huntsville, and who had given up his charge to become the

personal chaplain of General Rosecrans, was the one who

instructed and baptized General Stanley. It was in the autumn of

1862. Mass was celebrated in the public square of Iuka.

There was a very large attendance of the army; and before the

mass General Stanley read his profession of faith and received

conditional baptism. General Rosecrans was his sponsor. The news

of the incident spread at once through the whole army.

I was stationed with my regiment, the Fifth Minnesota, near

Corinth. I remember very well hearing the news and taking note

of the excellent impression produced by it. Not many weeks later

I met General Stanley, and he told me that he was most happy

in realizing that he had obeyed the calling of his conscience;

and that by so doing he was nearer to his God, and ready

to meet Him, if death came to him in the performance of his duty

on the battle field.

One Sunday morning I was

preparing the altar for the celebration of mass in the camp of

the Fifth Regiment, when

Stanley was seen coming forward to assist at the Holy Sacrifice.

I remember him well, kneeling on the ground among the

rank and file of the regiment, prayer book in hand and edifying

deeply, by his visible piety, all who were around him.

Catholics and non-Catholics expressed their respect for him on

account of his open profession. Catholics, in a special manner,

were drawn to a more fervent practice of their religion by the

noble example which they had witnessed. When he was,

in later days, on duty in the northwest, he occasionally passed

through St. Paul. Whenever he was here on Sunday

he was most punctual in attending mass. I met him frequently when

he lived in Washington, and found him to be,

in profession and practice, a most loyal Catholic.

The last time I shook hands with

him was one day in Lafayette Square, towards the close of the

Spanish War.

'How was General Stanley able to remain at home when war was

raging?' I asked, and the reply was, 'To an old soldier

this has been no war, made up as it is of what we would have

called morning skirmishes.'

The effect of my personal

relations with General Stanley was that I loved and esteemed him,

most sincerely,

as a noble soldier, a cultured gentleman, a true friend and

devoted Christian. He may have had a few frailties!

But, how small they were when seen together with his great

qualities of mind and heart!" * * * .

George Deshon, a graduate of

1843—second in the class with Franklin, Peck, Reynolds,

Hardie, Clarke, Augur,

Ulysses S. Grant, and other noble souls—served in the

Topographical Engineers and Ordnance, and was, for some

eighteen months, Assistant Professor of Ethics during Stanley's

cadet-ship. He resigned in 1851, and subsequently,

as Roman Catholic priest, became a member of the Congregation of

Redemptorists, and thereafter a member of the

Paulists. Now he is the Very Reverend Superior General of the

latter congregation. Inferably Stanley was led, through

observation of that eminently distinguished graduate, to that

study of Catholic doctrine which, eventually, made him a

Catholic. Deshon was an attractive man, and led men to love and

admire him. Among his particular admirers was Grant.

The latter, when President, had Deshon as his guest during his

visits to Washington ; and during the visits they were to

each other, as they had been at West Point—"Sam"

and "George."

Stanley believed, with the

Christian world, that "Prayer moves an arm that is almighty;

and that arm governs the world!"

Accordingly, he did not fail to supplicate—through the

universal prayer of the Catholic Church—our God of might,

wisdom

and justice, through whom laws are enacted and judgment decreed,

to assist with the holy spirit of counsel the President of the

United States, that his administration might be conducted in

righteousness, and be eminently useful to the people; and that

the light of divine wisdom might direct the deliberations of

Congress, to the end that they might tend to the preservation of

peace,

the promotion of national happiness, the increase of industry,

sobriety and useful knowledge, and the perpetuation, to the

people,

of the blessings of equal liberty. And, in his supplications, he

embraced the governors of states, and all judges and other

officers appointed to guard our political welfare; also all our

brethren and fellow citizens throughout the United States—

that they might be preserved in that,union and peace which the

world cannot give. For all, he asked unbounded mercy and

the blessings of this life.

The almighty arm of prayer has,

notably, its recognition in the concurrent resolution of the

Congress, and the proclamation

of the President under that resolution, in July, 1864,— both

based on penitential and pious sentiments at a time when

the gloom and grief of the United States were intensified. A day

of humiliation and prayer by the people was then proclaimed,

that they might repent and confess their manifold sins, and

implore the Almighty and Merciful Ruler of the Universe not to

destroy,

nor suffer us to be destroyed, as a people; and that the mind of

the nation might be enlightened to know and do His will,

humbly believing it to be in accordance with His will that our

place should be maintained, as a united people, among the family

of nations; and that effusion of blood might be stayed, unity and

fraternity restored, and peace established throughout our

borders.

Stanley understood the nature of

charity, as well enunciated by an eminent writer: * * * "As

we have no rights over ourselves,

and are bound to love ourselves with a rational love—that

is, with the love of knowledge, the knowledge that God has made

us;

and according to the laws which He has imposed upon our nature,

so we are also bound to love our neighbor as ourselves;

that is to say, he also is a creature of God, he is the property

and possession of God, just as I am, and I am bound to pay

to him the same respect, the same love, and the same honor, that

I am bound to pay to myself. If I see that his soul can be saved

by the loss of my temporal life, the law of Charity prompts me to

lose it. If I were to see that his temporal life could be saved

by the expense of my own, and even by the loss of my own, the law

of Charity bids me, if it does not bind me, to risk it.

If the risk of my own life were necessary to procure him some

great and signal good, charity would counsel me even to

risk my life for it. But there is one thing that I may not risk,

neither to gain any temporal good for myself, nor to gain any

temporal good for another— I may not risk my spiritual life

and my eternal salvation! The rational law of love for myself

there

comes in to limit my freedom. And though I may die for my

neighbor to save his soul, or even his life—the life of the

body—

I may not risk my spiritual life, or my salvation, for anything

whatsoever. This, then, is the nature of charity." * * * And

the

words of St. Paul: "that charity is 'the bond of

perfection;' that is to say, like as a golden thread that

sustains a string of pearls,

and runs through them all, or as a clasp of gold holds a vestment

together, so all the graces of the Holy Ghost, which

constitute the sanctification of the soul, are sustained, and

completed, and clasped together by charity. * * * 'Faith, hope

and charity. But the greater of these is charity' * * * because

charity makes faith and hope perfect." * * *

Stanley held to his true

greatness; and never did he covet false glory! Though living in

an age when "the material civilization

of the world has been piled up to a gigantic height," he

stood among the many great and good, "to testify that there

is an

order higher still; that as the soul is more than the body, and

eternity than time, so the moral order is above the material;

that

justice is above power; that justice may suffer long, but must

reign at last; that power is not right; that no wrongs can be

sanctioned

by success; nor can the immutable laws of right and wrong be

confounded."

He did not fail to assert that

it is part of the Christian religion to obey "the powers

that are," and that there are two distinct

and separate powers—the spiritual and civil—with

"distinct and separate spheres, and that within these

spheres, respectively,

they hold their power from God," from whom all power comes.

This tenet is illustrated by the forcible entry of French troops,

in 1809, into the Quirinal Palace. In the hall of the palace

stood the Holy Father, Pius VII; before him stood General Radet,

the commander of the troops. For the moment they stood in

silence. Afterward someone asked Radet: "Why did you not

speak?"

He replied: "I felt to be myself as long as I was ascending

the stairs, and was in the midst of the Swiss and the soldiers.

When I came to stand in the presence of the Vicar of Jesus

Christ, my first communion rose up before me!" In time he

recovered self-control and said: "Holy Father, by command of

the Emperor, I must call on you either to abdicate your

temporal dominion or to go with me to prison." The Holy

Father answered: "You have done right to fulfill the command

of your master, the Emperor, because you have sworn fidelity to

him; and I must do my duty which binds me to my Master.

He has committed to me the Temporal Power of the Holy See, as a

trust in behalf of the Universal Church, and resign it

we ought not, we will not, we cannot." The Holy Father thus

rigidly protested against the despoilment of the

patrimony of St. Peter's successors !

Stanley, when exercising

command, held rigid views as to obedience: "Beware of

disobedience! Beware, also, not of

actual disobedience, but of that tardy, slothful negligence by

which we may provoke!" He said to the graduates of 1885:

"I beseech you to obey orders ; mark your duties with

fidelity; observe strictly the articles of war; do exactly as you

will

promise in your oath of office—that is to say, obey the

orders, of the President of the United States, and the orders of

the

officers appointed over you, according to the rules and articles

of war. Do not waste time in construing orders; it is extremely

improbable that any officer of the army will give you an illegal

order; if he does, you will receive all due protection."

Stanley did not hate any man! He

did, however, hate the evil in the man, as he hated the evil in

himself; and he

condemned both alike. He was tolerant towards the person, but

intolerant of the evil in him! When he spoke of that evil,

as was his wont, he used words most positive. Yet he stoutly

strove to follow the injunction: "Bear the same heart toward

your neighbor which you desire your neighbor to bear toward you.

Be conscious of your own dignity, and be conscious

of the dignity of others. Let us learn to have a delicate

conscience to understand promptly, and to correspond, if we can,

proportionately." Such was his line of thought that he

studied character—that intellectual, and, as expressed by a

thoughful

writer, "moral texture into which, all our life long, we

have been weaving up the inward life that is in us. It is the

result of the

habitual or prevailing use we have been making of our intellect,

heart and will. We are always at work, like the weaver

at the loom; the shuttle is always going, and the woof is always

growing. So we are always forming a character for

ourselves." * * * "If a man is habitually proud, or

vain, or false, and the like, he forms for himself a character

like in kind."

As a result he could read men by their faces—not simply by

looking at their God-made features, "but at a certain cast

and motion, and, shape and expression, which their features have

acquired; in brief, the countenance, which is the index

of character, and which stands, in its delineation, good or bad,

just as the shuttle ever going invariably in the heart

has made it." The fruit of the loom will be ripe and

perfect, or defective, just as man's free will—the motor for

the

shuttle in the heart—shall have produced it.

* * * "What they are within

they are without. Countenance is transparent, and the soul shines

through. And they who are

calm and bright, have a gentle expression; why is it so? Because

things that are bright, and calm, and sweet, and, beautiful,

God and His goodness and the world to come, the hopes that bear

them up, the trust which they know can never fail—

these diffuse over their whole mind and heart, the brightness and

sweetness of the realities which are ever before their

sight."

Stanley had in view the famous

inscription, "Know Thyself," as engraved on the front

of Appolo's Temple at Delphi,

of which it has been said that it is so beautiful in expression,

and so profound in sense, that it could not have come from man,

and must have come from heaven. And, in this connection he

accepted the words of advice * * * "you would be much better

if you know yourself, than if, neglecting yourself, you should

lose your time studying the course of the planets, the nature of

man,

the structure of animals, and all the wonders of heaven and

earth. Some know many things and know not themselves, though

true philosophy consists in self-knowledge. * * * Its principal

effect is to produce in us humility, to the acquisition of

which it contributes wonderfully, and of which it is the origin *

* * for if we consider ourselves, interiorily, with the laws

of truth, the sight of our great poverty and profound misery must

humble and make us vile in our own eyes."

Accordingly Stanley endeavored

to find the means to acquire self-knowledge; and soon ascertained

that we must consider

ourselves attentively, and "study and comprehend that, of

ourselves, we are nothing." He considered our miseries as

manifested

through our falls, and corporeal pains and innumerable maladies;

and "the experience of our miseries, the infirmities of our

bodies, and the weakness of our souls," taught him the

necessity for humility, and that he, of himself, was nothing, had

nothing,

and could not do anything. He thus escaped the spirit of pride,

to which our natures incline us; and, resultingly, he could

say—

with a high sense of hope.: "The Lord is the protector of my

life, who shall make me trouble? Though I should walk in the

midst of the shadows of death, though whole armies were ranged in

battles against me, I shall fear no evil because thou

art with me!" With a character as indicated, Stanley left

this world.

The funeral services, at St.

Matthew's Church, were solemn and impressive. The holy mass of

requiem, the mourning

habiliments of the altar, and the appropriate vestments of the

priest; the music, melodious and pathetic; the flowers and

lights;

the delegations from patriotic societies; the throng of mourning

friends; the large military escort of cavalry, artillery

and engineers. All, simply and suitably, marked the occasion.

At the National Soldiers' Home

hundreds of veterans, inmates of the home, bordered the roadway

between the entrance

to the park and the grave; all standing with bowed

heads—some in tears. The solemn commitment services were

followed by the volley of musketry, the Major General's salute

and "taps." So closed the earthly honors extended to

the

remains of the eminently distinguished officer, who had served so

well—as a soldier of the cross, and as a soldier of his

country.

He who had studied the question: "Whither am I going;

whither leads my way."

I knew Stanley intimately,

dating from West Point where, for three years, we were together

as cadets. There, for some time,

he was the leader of the choir of the Cadet Chapel, and at his

instance I became a member of the organization. Inferably

he had to do with an invitation to me from his

classmates—Sheridan and Kautz—to tent with them during

the encampment

of 1849. All of us were from Ohio. After the Civil War we were

together in Texas. For a part of the time he was the

Commanding General of the department, while I was the Adjutant

General. We were close friends, officially and socially—

were together on duty and off duty; walked, rode and visited with

pleasant association. Once, when I was seriously ill,

he and his family extended to me the close attention and

affection of their home. Again we were intimately associated

during and after his governorship of the Soldiers' Home. I

enjoyed the charming hospitality of his house, and he was often

my guest. After his relief as governor, he said to me: I long to

visit Europe, and particularly the Holy Land. If I do so,

I must go soon, else it will be too late. I have reached that

time when I experience the natural effect of years; in the

natural

order I have not much time left. He made the tour, and I shall

ever treasure his recitals connected with it. He spoke of art and

artists, and scenes in the Holy Land; in connection with the

former he referred to paintings of a religious character.

I now recall his last hours—during which, undoubtedly, he

thought of the other world and its "Hall of Judgment;"

and I associate his thoughts with the dream of the artist, Hans

Memling, in his picture (painted 1467), portraying the

"Last Judgment," as referred to in the words of Mary F.

Nixon-Roulet, as follows:

* * * "In the central

portion of the triptych is enthroned our Lord—

'With calm aspect and clear, Lightning divine, ineffable,

serene.'

Calmly grave of expression,

seated on a radiant rainbow, a great golden ball for his

foot-stool. Behind him is the

flaming sword of Divine Justice, while four lovely angel-figures,

floating aloft, bear the instruments of his passion.

The Blessed Virgin kneels at one side, St. John Baptist at the

other, and the twelve Apostles are grouped about,

stately figures with fine heads, their flowing robes well

painted. Below stands St. Michael, a glorious knight-militant

in golden armor, his wings beautiful with peacock feathers.

'In stature, motion, arms, Fit to decide the empire of great Heaven,'

he holds the scales, weighing

the good and bad. At one side of the triptych is the way of the

Blessed,

where St. Peter welcomes them, and

'A glorious company, men and

boys,

The matron and the maid, Around the Savior's throne rejoice,

In robes of light arrayed.'

Radiant is the sight of those

redeemed souls, as with floating garments they sweep up the

golden stairs toward the

Gate Beautiful. Wonderful is the contrast on that other side,

where the lost souls, finding not a blessed future,

are tortured according to the vigorous mediaeval ideas of hell, a

place of physical torture so intense as to well-nigh work

madness."

I was near Stanley during his

last illness, and conversed with him not many hours prior to his

last breath. During that

interview he said to one of his daughters—who was sadly

distressed, knowing that the end was near—"Be brave, my

child,

I fear not!" Calmly and courageously he yielded to the

embrace of death, believing in the mercy of the Supreme Judge,

who "is able to cast up a very large debit and credit

account in a great ledger, and strike a true balance." He

hoped to ascend

"the golden stairs to the Gate Beautiful!" At that, my

last interview with him, may I not say that, in retrospect, he

reviewed

his cadetship, and the dangers of battle and hazardous service of

the officer, through which he had safely passed? I couple

with his dying hours the words of Fitz-James O'Brien, "The

Countersign"—that particularly important word intrusted

to Stanley,

for the first time, in his early cadet life:

"Alas! The weary hours pass

slow;

The night is very dark and still, And in the marshes far below

I hear the bearded whip-poor-will. I scarce can see a yard ahead;

My ears are strained to catch each sound; I hear the leaves about

me shed,

And bubbling springs burst through the ground.

Along the beaten path I pace,

Where white rags mark my sentry's track; In formless shrubs I

seem to trace

The foeman's form, with bending back. I think I see him crouching

low;

I stop and list-—I stoop and peer, Until the neighboring

hillocks grow

To groups of soldiers far and. near.

With ready piece, I wait and

watch

Until my eyes, familiar grown, Detect each harmless earthen

notch,

And turn guerrillas into stone; And then, amid the lonely gloom,

•

Beneath the weird old tulip trees. My silent marches I resume,

And think on other times than these.

So rose a dream—so passed a

night—When distant in the darksome glen,

Approaching up the sombre height, I heard the solid rnarch of

men;

Till over stubble, over sward,

And fields where lay the golden sheaf,

I saw the lantern of the guard Advancing with the night relief.

'Halt! Who goes there?' my

challenge cry;

Tt rings along the watchful line. 'Relief!' I hear the voice

reply.

'Advance and give the countersign!' With bayonet at the charge, I

wait—

The corporal gives the mystic spell; With arms at port, I charge

my mate,

And onward pass, for all is well. ²

Stanley, later in life, in his service

uniform as Brigadier General

Note that in this portrait he is not wearing his Medal of Honor,

as he had not yet been awarded it. This photo was taken circa

1884-1892.

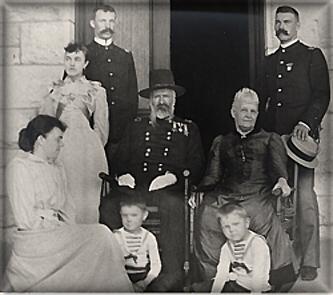

Pictured above are General Stanley and

some of his family, at their quarters, the commandant's house,

also called

the Pershing House, at Fort Sam Houston, Texas, during Stanley's

tenure as Commander of the Department of Texas.

The officer standing at the right is General Stanley's Aide, Capt

William A. Holbrook, who not only married General Stanley's

daughter Josephine, but in 1918, as Major General Holbrook, would

occupy Pershing house himself. Photo taken 1884-1892.

The above photo from the US Army Medical Department Center and School Website

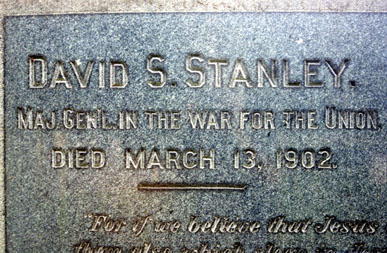

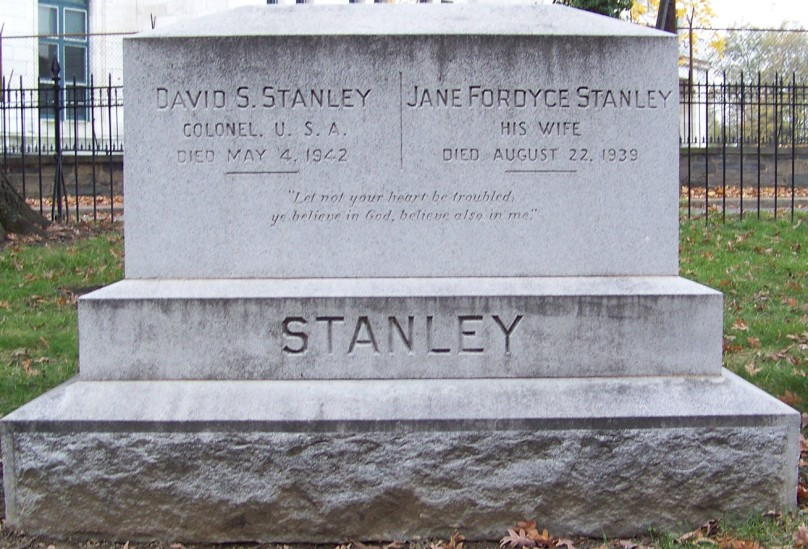

Burial:

US Soldiers' and Airmen's Home National Cemetery

Washington

District of Columbia

District Of Columbia, USA

Plot: Section O-20

Grave monument for David S. Stanley

Photo by don connelly from the Find A Grave website

Grave plaque for David S. Stanley

Photo by don connelly from the Find A Grave website

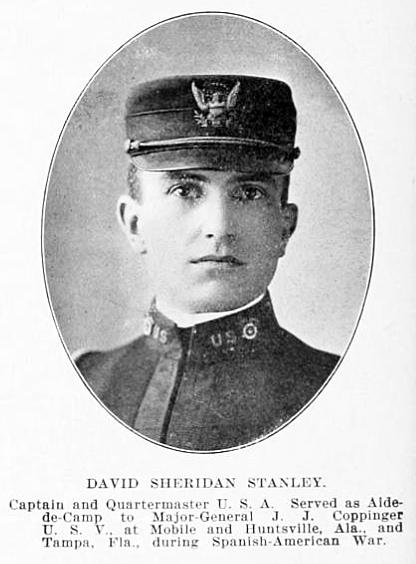

David Sloane Stanley had seven

children, all girls except for one son, David Sheridan Stanley.

David Sheridan Stanley would also have an Army career, lasting

thirty-two years, more than seven

of those years assigned to the 22nd Infantry.

David Sloane Stanley's son was

to be called David Sloane Stanley after his father but received

his middle name

in a rather anecdotal way. The boy was born at Fort Sully, Dakota

Territory, a post commanded by his father,

who at the time was also Commander of the 22nd Infantry.

A week after the boy was born

Lieutenant General Phillip H. Sheridan, Chief of Staff of the

Army and

West Point classmate of Stanley was on an inspection tour of the

frontier. Sheridan's duties took him to the post

at Fort Sully and he visited Stanley's home to pay his respects

to his old friend and classmate and to see

Stanley's newborn son:

"With

Mrs. Stanley still in bed, the oldest daughter, 12-year-old

Josephine, carried the infant out on a pillow

to show him. Sheridan asked the infant's name. Josephine, likely

nervous in the presence of such a famous

person, blurted out: David Sheridan Stanley. The vain

Sheridan had to be gratified by the family's wisdom

and continued friendship, and thus little David was christened

Sheridan, not Sloane. Considering Stanley's

lack of political acumen, his daughter's jitters likely did as

much for his careeer as he himself could have

accomplished in a decade." ³

Most of the Stanley

family in front of their home, the commanding general’s

quarters at Fort Sam Houston, 1886.

Brigadier General David Sloane Stanley is seated, third from left

with his hat in his lap and with his Aide, 1st Lieutenant

Oskaloosa Smith

(of the 22nd Infantry) standing behind him. On the far right

seated on the horse is David Sheridan Stanley. Four years after

this photo

was taken David would enter the US Military Academy at West

Point.

Photo from the website: Anna Stanley An American Impressionist

David Sheridan Stanley circa 1895-1901

Photo from "A military album, containing

over one thousand portraits of commissioned officers who served

in the Spanish-American war"

L.R. Hamersly 1902.

David Sheridan Stanley was born

in North Dakota (Dakota Territory) on September 10, 1872 while

his father was

Commander of the 22nd Infantry. At the age of seventeen David

entered the US Military Academy on June 17, 1890.

On June 11, 1892 he was turned back to repeat his second year. On

June 12, 1895 he graduated 42 out of a class

of 52. His best subjects were Drill Regulations and Practical

Military Engineering and his worst subjects were

Chemistry and Civil Engineering. Upon graduation he was

commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant in Company K of

the 22nd Infantry.

David served a year with the

22nd Infantry at Fort Keogh, Montana. He was then detailed by the

Secretary of War

to follow a course of instruction at L'Ecole de Cavalerie in

Saumer, France from August 8, 1896 to January 10, 1898.

After the declaration of war against Spain he was appointed

Acting Ordnance Officer of the 1st Independent Division

at Mobile, Alabama on May 12, 1898 as the Division prepared for

deployment to Cuba. That same month the